A French Fighter Ace (Nov 2016)

In Britain we can look back with pride on our many heroes in WWII. The Battle of Britain, the long, sustained courage of the bomber crews - just two of a long list of successes and sacrifices of our fighting airman.

In France, it is somewhat different. Their war began in earnest on 10 May 1940, and in six weeks it was all over. French forces were scattered and any remaining units confined to the Vichy-government controlled Algeria and Syria. But the French do have their flying heroes.

In 1943, General de Gaulle thought that the Free French should be seen to be more active with an independent force so he set up a fighter squadron to operate on the Russian front. The Normandie-Niemen regiment grew from 12 pilots and 47 ground crew to three squadrons which fought valiantly from mid-1943 to May 1945 claiming 273 enemy shot down. Of the 100+ pilots who flew in Russia 52 of their number were killed. The survivors were greeted as heroes when they came home with 37 Yak-3s and numerous French and Russian decorations. Today, they are still enthusiastically celebrated by the Russians (as are 151 Wing of the RAF who took their Hurricanes to Murmansk in 1941).

One French pilot usually assumed to have fought in Russia actually made his name elsewhere. In the brief defence of France in 1940 he achieved fame by becoming an ‘ace in a day’. Although his name is included with the many on war memorials he is specially commemorated in his home town.

In France, it is somewhat different. Their war began in earnest on 10 May 1940, and in six weeks it was all over. French forces were scattered and any remaining units confined to the Vichy-government controlled Algeria and Syria. But the French do have their flying heroes.

In 1943, General de Gaulle thought that the Free French should be seen to be more active with an independent force so he set up a fighter squadron to operate on the Russian front. The Normandie-Niemen regiment grew from 12 pilots and 47 ground crew to three squadrons which fought valiantly from mid-1943 to May 1945 claiming 273 enemy shot down. Of the 100+ pilots who flew in Russia 52 of their number were killed. The survivors were greeted as heroes when they came home with 37 Yak-3s and numerous French and Russian decorations. Today, they are still enthusiastically celebrated by the Russians (as are 151 Wing of the RAF who took their Hurricanes to Murmansk in 1941).

One French pilot usually assumed to have fought in Russia actually made his name elsewhere. In the brief defence of France in 1940 he achieved fame by becoming an ‘ace in a day’. Although his name is included with the many on war memorials he is specially commemorated in his home town.

By the outbreak of war in 1939 he was a Sergeant, a fully trained fighter pilot flying the Morane-Saulnier 406, the ‘best hunter in the world’, according to the General Staff. Based near Chartres in northern France, the pilots of GC III/6 found little to break the routine of regular patrols. On 23rd November le Gloan, now a Warrant Officer, was airborne with Lt Martin, searching for a Dornier 17P reconnaissance bomber. After an hour’s search, a new position report led them to the Dornier which they attacked together.

The Dornier dived steeply and tried to escape by hedge hopping. For fifteen minutes the Moranes attacked repeatedly until the Dornier was forced to crash land. The three crew were taken prisoner and the Moranes flew home to celebrate the squadron’s first victory – and for the eight bullet holes in Pierre’s Morane’s tail to be repaired.

It’s appropriate at this point to appreciate that the French method of scoring victories was very different from the RAF’s. Aircraft destroyed on the ground counted equally with those shot down. Probables and damaged claims were generously assessed. Shared victories were often credited to both pilots, indeed, it was not unknown for pilots in a group to earn a score just by being there, even when they had not fired their guns. (The best-known case of a damaged reputation as a result of this scoring method was Pierre Clostermann’s, author of ‘The Big Show’. His 33 French-style claims were widely disputed. When the claims were strictly analysed RAF-style they were assessed by some to be as few as 11).

Le Gloan added another Dornier to his score on 2nd March 1940. Then the German offensive began on 10th May. In the confused fighting, the French squadrons were overwhelmed by the attackers. Le Gloan claimed a couple of Heinkel 111s on the 11th and 14th but his unit suffered badly. The CO was lost, other pilots were shot down and taken prisoner and several Moranes were written off in ground attacks. On 31st May the squadron was reduced to five aircraft and was pulled back to Toulon to recuperate and to be re-equipped with Dewoitine 520s.

The Dewoitine was faster and more manoeuvrable than the Morane. Difficult to fly, (Eric Brown thought it a ‘nasty little brute’), it would spin easily off a turn and even on the ground its steering was unpredictable). The squadron was still getting to grips with their new machines when they found themselves in the front line again. Mussolini declared war on France.

On the 13th June Italian bombers and fighters raided Toulon and strafed several French airfields. Le Gloan was in action and claimed two Fiat BR 20 twin-engined bombers.

Two days later a second larger raid (two groups of bombers and dozens of escorting Fiat CR 42s) approached. Le Gloan found his machine unserviceable and ran to another, leaving his parachute behind.

Two days later a second larger raid (two groups of bombers and dozens of escorting Fiat CR 42s) approached. Le Gloan found his machine unserviceable and ran to another, leaving his parachute behind.

He took off with two other D520s but one soon had to return with a faulty propeller. Pierre and Capt Assolant climbed up to a formation of ten CR 42s and attacked the rear section of three.

They used a favourite line of attack – a zoom climb from below and behind into the enemy’s blind spot. One of the Fiats burst into flames (it was later learned that the pilot somehow got it back home) and the pilot baled out of a second. Le Gloan and Assolant shared the victories. The formation scattered and soon the sky was empty. So was Assolant’s supply of ammunition and he broke off to return to base.

They used a favourite line of attack – a zoom climb from below and behind into the enemy’s blind spot. One of the Fiats burst into flames (it was later learned that the pilot somehow got it back home) and the pilot baled out of a second. Le Gloan and Assolant shared the victories. The formation scattered and soon the sky was empty. So was Assolant’s supply of ammunition and he broke off to return to base.

Now alone, Le Gloan saw some AA bursts in the distance. They were being aimed at three CR42s apparently on their way home. They spotted the French fighter and broke formation. Le Gloan followed one, scoring so many hits as it dived away that Pierre felt quite justified in registering a claim when he got home. Suddenly he was attacked by eight Fiats and it was his turn to dive away to escape.

Then he received a radio message to fly to the airfield at Luc which was being strafed by a group of CR 42s. He got there in time to surprise one of the Italians with a burst of the last of his cannon shells – his fourth victim in a busy flight. It was time to go home.

He was in the circuit preparing to land when he saw a lone aeroplane 4000 metres above. It was a Fiat BR 20 taking photographs of the results of the raids. After a long climb he attacked, using only his four machine guns. Repeated passes resulted in the bomber falling in flames.

He landed after this action-packed 40 minute flight. Five in one flight echoed the achievements of René Fonck, the highest-scoring Allied pilot in the First World War. Fonck was still serving in 1940 as a Lt. Colonel and came specially to congratulate le Gloan and announce his promotion to Sub Lieutenant. He was awarded the Military Medal and, a few days later, made Chevalier of the Legion d’Honneur.

Then he received a radio message to fly to the airfield at Luc which was being strafed by a group of CR 42s. He got there in time to surprise one of the Italians with a burst of the last of his cannon shells – his fourth victim in a busy flight. It was time to go home.

He was in the circuit preparing to land when he saw a lone aeroplane 4000 metres above. It was a Fiat BR 20 taking photographs of the results of the raids. After a long climb he attacked, using only his four machine guns. Repeated passes resulted in the bomber falling in flames.

He landed after this action-packed 40 minute flight. Five in one flight echoed the achievements of René Fonck, the highest-scoring Allied pilot in the First World War. Fonck was still serving in 1940 as a Lt. Colonel and came specially to congratulate le Gloan and announce his promotion to Sub Lieutenant. He was awarded the Military Medal and, a few days later, made Chevalier of the Legion d’Honneur.

For several days, bad weather hampered air operations. On the 24th June an armistice with Italy was agreed.

|

The armistice with Germany was signed on 10 July 1940. The anglophobe Vichy government was allowed to retain military units in Algeria and Syria for defence against the British. (Churchill had already shown his hand by ordering the Royal Navy to bombard the French fleet in harbour in Dakar when they had refused to come out and join the Allies). The French retaliated with a couple of bombing raids on Gibraltar before settling down to a period of armed neutrality.

|

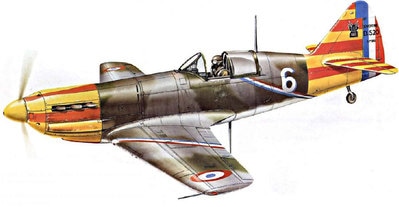

Now based in Algeria, Pierre le Gloan’s squadron had flown there in aeroplanes still bearing French markings but with the rear fuselages painted yellow. Pierre’s No 6 also proudly carried the diagonal stripe of the Ace.

In Iraq, Rashid Ali staged a coup in April 1941. On 2nd May he moved his troops to besiege RAF Habbaniya and began shelling the camp. (Our friend and AEG member, Ian Blair, was there, digging defensive trenches). Germany offered support to Rashid Ali by sending a number of transport aircraft, painted in Iraqi markings, on an ‘air bridge’ to neighbouring Syria. To beef up the defences they allowed French fighters to move from Algeria to Syria.

Thus Pierre found himself in transit via Italy and Greece. There he met an ex-enemy. When he shot down the Dornier in early 1940 the pilot had been captured and entertained to dinner in the French squadron mess. He happened to be stationed in Athens in 1941 and was delighted to meet le Gloan, insisting on returning the hospitality with a festive tour of the Athens night clubs. Pierre then completed his 3,800 km journey to Lebanon.

In Iraq, Rashid Ali staged a coup in April 1941. On 2nd May he moved his troops to besiege RAF Habbaniya and began shelling the camp. (Our friend and AEG member, Ian Blair, was there, digging defensive trenches). Germany offered support to Rashid Ali by sending a number of transport aircraft, painted in Iraqi markings, on an ‘air bridge’ to neighbouring Syria. To beef up the defences they allowed French fighters to move from Algeria to Syria.

Thus Pierre found himself in transit via Italy and Greece. There he met an ex-enemy. When he shot down the Dornier in early 1940 the pilot had been captured and entertained to dinner in the French squadron mess. He happened to be stationed in Athens in 1941 and was delighted to meet le Gloan, insisting on returning the hospitality with a festive tour of the Athens night clubs. Pierre then completed his 3,800 km journey to Lebanon.

Meanwhile 12 Messerschmitt 110s, 7 Heinkel 111s and 20 Ju 52/3m passed through Syria on their way to Mosul in northern Iraq. German aircraft were found in Syria by an RAF Blenheim thus confirming that the Vichy Government had broken the terms of its neutrality. The Germans launched sporadic raids on Habbaniya and the RAF had to retaliate. On 14th May Curtis P-40 Tomahawks, in their first wartime operation, strafed the airfield occupied by le Gloan’s GC III/6, damaging six Dewoitines.

Rashid Ali’s forces were defeated by a spirited aerial offensive carried out by the modified training aircraft based at Habbaniya. By the end of May his troops had pulled back to Baghdad and Ali fled the country. The Germans melted away leaving most of their aeroplanes - and their reputation with the Arabs - as wrecks. The Allies assembled a multi-national force to invade Syria. Most were Australians, but there were also many Indian troops, Scottish Commandos, Free French, cavalry from the Arab Brigade – even a special Jewish unit led by Moshe Dayan, who was to lose an eye in the fighting and ever afterwards wore a prominent black eye patch. Both Allied and Vichy forces included contingents of French Foreign Legion soldiers drawn from all nations.

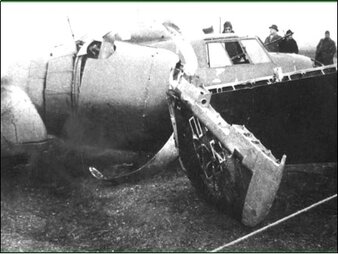

The records of the air fighting are incomplete and occasionally contradictory but the claims made by le Gloan are clear enough. On 8th and 9th June, he and three colleagues shot down three Hurricanes. On the 15th le Gloan was leading a section of three Dewoitine D 520s which dived onto a group of six Gladiators. Pierre shot down one of the Gladiators but the others used their superior manoeuvrability to fight back. Pierre’s D 520 was hit and his engine failed. Streaming oil he glided down, ‘escorted’ by two Gladiators who watched his belly landing on rough ground which destroyed his aeroplane. Le Gloan was unhurt.

On the 23rd June two groups of Hurricanes strafed his airfield and le Gloan managed to get airborne and shoot down a Hurricane of the second group. Later in the day he tangled with 12 Tomahawks of an Australian squadron. His aeroplane was damaged and twice fell into a spin. The second recovery was perilously close to the ground and he was lucky to be able to land safely.

Pierre’s last claims were for two Hurricanes on the 5th July. The fighting ended on the 12th. Of the 37,000 Vichy prisoners, 5.000 elected to join de Gaulle’s Free French, the rest were repatriated to France or Algeria. Le Gloan, of course, had not been taken prisoner. He flew out with the remnants of his unit to Rhodes heading for Algeria.

The records of the air fighting are incomplete and occasionally contradictory but the claims made by le Gloan are clear enough. On 8th and 9th June, he and three colleagues shot down three Hurricanes. On the 15th le Gloan was leading a section of three Dewoitine D 520s which dived onto a group of six Gladiators. Pierre shot down one of the Gladiators but the others used their superior manoeuvrability to fight back. Pierre’s D 520 was hit and his engine failed. Streaming oil he glided down, ‘escorted’ by two Gladiators who watched his belly landing on rough ground which destroyed his aeroplane. Le Gloan was unhurt.

On the 23rd June two groups of Hurricanes strafed his airfield and le Gloan managed to get airborne and shoot down a Hurricane of the second group. Later in the day he tangled with 12 Tomahawks of an Australian squadron. His aeroplane was damaged and twice fell into a spin. The second recovery was perilously close to the ground and he was lucky to be able to land safely.

Pierre’s last claims were for two Hurricanes on the 5th July. The fighting ended on the 12th. Of the 37,000 Vichy prisoners, 5.000 elected to join de Gaulle’s Free French, the rest were repatriated to France or Algeria. Le Gloan, of course, had not been taken prisoner. He flew out with the remnants of his unit to Rhodes heading for Algeria.

He was delayed again at Athens. Taxying out to the runway he dropped a wheel into a newly dug cable ditch. The damage was limited to the twisted tip of one propeller blade. With no preplacement available, his mechanics sawed 12 cms off the tips of all three blades and Pierre was able to follow his squadron. Just for the record, it should be noted that the Vichy markings had changed and Pierre’s mount now looked like this.

He was delayed again at Athens. Taxying out to the runway he dropped a wheel into a newly dug cable ditch. The damage was limited to the twisted tip of one propeller blade. With no preplacement available, his mechanics sawed 12 cms off the tips of all three blades and Pierre was able to follow his squadron. Just for the record, it should be noted that the Vichy markings had changed and Pierre’s mount now looked like this.

Settling into a more peaceful life in Algeria, Pierre was promoted to Lieutenant. The following year, on the 8th November 1942, the Allies landed in Algeria. The French records show that the weather was too foggy for air operations so the landings were not opposed. Now the Vichy French had to learn again to collaborate with their previous opponents.

After a brief flirtation with the P-38 Lightning, three French squadrons were equipped with the P-39 Airacobra. The weight of the P-39’s heavy 37mm cannon in the nose was balanced by the mid-mounted engine which led to cooling problems and frequent engine failures. Some months were spent in conversion to the new type. Pierre’s disappointment with the P-39 was alleviated by his marriage to Mireille on 25th June 1943 and, on the very next day, by his promotion to Captain and commander of his Squadron.

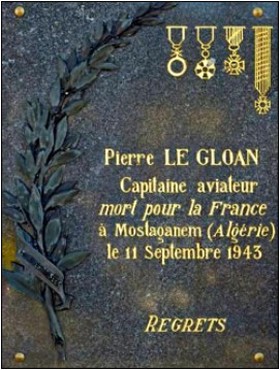

On 11th September, le Gloan and Sergeant Colomb took off on a routine early morning patrol. Not far from the coast, Colomb noticed smoke coming from Pierre’s engine. They turned back but the engine failed before they reached the airfield. Pierre lined up for yet another forced landing. Unfortunately, he either forgot that his aeroplane was fitted with a belly tank or the release mechanism failed. When it touched the ground, the tank exploded. Pierre died instantly.

Le Gloan’s record of 14 (4 German, 7 Italian and 7 British) makes him the 4th highest scoring French pilot in WWII.

There was much speculation about what might have happened had he survived the forced landing. Further promotion could have been difficult because there was a gulf in the Air Force between the Free French units and the ex-Vichy units. It was more likely that le Gloan would have volunteered to join the Normandy Niemen, as several other French pilots in Algeria did, and possibly become the greatest French ace of WWII.

Le Gloan’s record of 14 (4 German, 7 Italian and 7 British) makes him the 4th highest scoring French pilot in WWII.

There was much speculation about what might have happened had he survived the forced landing. Further promotion could have been difficult because there was a gulf in the Air Force between the Free French units and the ex-Vichy units. It was more likely that le Gloan would have volunteered to join the Normandy Niemen, as several other French pilots in Algeria did, and possibly become the greatest French ace of WWII.

He was buried in Algeria and as time passed, his memory faded and became tangled and obscured by the Normandy Niemen achievements. Not in his home town. As well as naming a street after him they held a special parade to celebrate the anniversary of his birth.