Gordon Vette (Apr 2015)

The Air New Zealand DC-10 was on a routine flight from Fiji to Auckland. It was 21st December 1978, and many of the passengers were looking forward to their Christmas leave at home. At the controls of Flight NZ103 was Capt. Gordon Vette. Thirty years previously, he had joined the airline as an engineering apprentice. After a five year break in the RNZAF where he finished as a top rated flying instructor, he rejoined the airline and gained his licences both as pilot and navigator. By 1978 he was a Check and Training Captain.

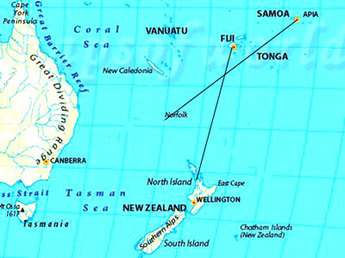

The routine of the flight was interrupted by a Mayday call. The aircraft in trouble was a Cessna 180 Agwagon. It had taken off from Pago Pago in American Samoa for the next leg of its delivery flight to Australia. The destination was Norfolk Island, a flight of 1740 miles across the Pacific but its ETA had passed and the island was nowhere in sight. The pilot, Jay Prochnow, a former US Navy pilot, realised that his ADF had been giving false readings and he was totally lost. He put out his Mayday call and began an expanding square search. NZ 103 was the nearest aeroplane and was asked to help.

The routine of the flight was interrupted by a Mayday call. The aircraft in trouble was a Cessna 180 Agwagon. It had taken off from Pago Pago in American Samoa for the next leg of its delivery flight to Australia. The destination was Norfolk Island, a flight of 1740 miles across the Pacific but its ETA had passed and the island was nowhere in sight. The pilot, Jay Prochnow, a former US Navy pilot, realised that his ADF had been giving false readings and he was totally lost. He put out his Mayday call and began an expanding square search. NZ 103 was the nearest aeroplane and was asked to help.

Vette’s navigation skills were then put to the test. He began working out the position of the Cessna by asking him for his heading when flying directly towards the sun. It was 274°. The DC-10’s heading was 270° so the Cessna was south of the DC-10. Next Prochnow was asked to measure the elevation angle of the sun by extending his arm and using his fingers as a sextant – four fingers. In the DC-10 it was two fingers. Vette estimated that the Cessna was about 250 miles further west. By keeping his passengers informed they tolerated the delay to their flight and became involved, every window crammed with eyes scanning the empty sea below

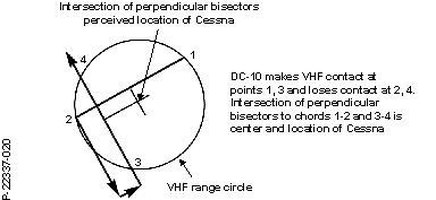

Knowing that the Cessna’s VHF radio would have a range of 200 miles Vette flew an aural box pattern whilst Prochnow transmitted and he was able to establish their relative positions when they were 200 miles apart. A check of the exact time of sunset by Prochnow and Norfolk Island helped. All these calculations, of course, had to be adjusted to take into account the different altitudes of the aeroplanes. The Cessna was estimated to be 290 south east of Norfolk Island.

By now, the sun had set and Prochnow had been airborne for over 20 hours. On the dark sea below he saw a light. It was a towed oil rig and from its known position he was told that had less than 150 miles to go. It was almost midnight, nearly eight hours after its original ETA, when the Cessna landed after 23 hours 5 minutes in the air.

By now, the sun had set and Prochnow had been airborne for over 20 hours. On the dark sea below he saw a light. It was a towed oil rig and from its known position he was told that had less than 150 miles to go. It was almost midnight, nearly eight hours after its original ETA, when the Cessna landed after 23 hours 5 minutes in the air.

Gordon Vette’s outstanding airmanship was recognised by awards from the Guild of Air Pilots and Navigators and from the President of MacDonnell Douglas. The story is also re-told in a book and an American TV movie.

The following year, Vette became involved in the aftermath of another, much more serious, occurence. In 1977 Air New Zealand had introduced scheduled sight-seeing flights to the Antarctic – a sweep of McMurdo Sound and a view of Mt. Erebus, a 12,447-foot volcano, all accompanied by a commentary from an expert. For the fourteenth of these popular flights, Sir Edmund Hillary had been booked as guide but he had to cancel and his friend, Peter Mulgrew, took his place. Flight 901 left Auckland at 8.00 am on 28 November 1979. Captain Jim Collins had not flown to Antarctica before but he was an experienced pilot and, with his co-pilot, had attended a full briefing 19 days before.

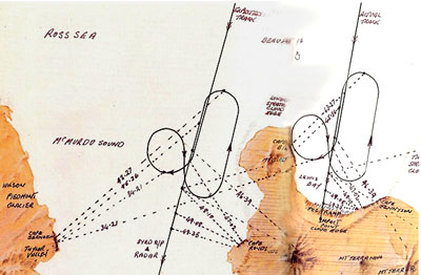

After four hours flying, the crew were in contact with the radar station at McMurdo and given permission to descend to 10,000’ and then ‘continue visually’. Although there was a regulation prohibiting flights below 6000’ photographs taken on previous flights showed that the DC-10s had routinely flown down McMurdo Sound at much lower altitudes. Collins descended below a 2000’ cloud layer, monitoring his position by the coastlines clearly visible 10 and 13 miles away on either side.

Suddenly, there was an alarm from the ground proximity warning system. Six seconds later, the DC-10 crashed into the side of Mt Erebus. The aircraft disintegrated and all on board were killed.

Suddenly, there was an alarm from the ground proximity warning system. Six seconds later, the DC-10 crashed into the side of Mt Erebus. The aircraft disintegrated and all on board were killed.

The accident stunned the airline and the nation. The grim process of recovering the bodies and wreckage for accident investigation was particularly difficult. The findings of the investigation were published on 31 May 1980 and concluded that the cause was ‘pilot error’.

This was not well received, particularly since it emerged that there had been changes to the flight plan and the crew had not been informed. At Jim Collins’ original briefing, which included an audio-visual presentation showing the flight down McMurdo Sound, there had been another captain who made his flight just four days later. During this, he noticed an error in the programmed flight plan but he was able to fly the usual route into the sound in good visibility. The computer generated plan was checked and the error – a ‘4’ instead of a ‘6’ – amended. Collins and his crew were not told of this ‘minor’ correction but, remarkably, it had the effect of moving his approach to Antarctica 30 miles eastwards.

This was not well received, particularly since it emerged that there had been changes to the flight plan and the crew had not been informed. At Jim Collins’ original briefing, which included an audio-visual presentation showing the flight down McMurdo Sound, there had been another captain who made his flight just four days later. During this, he noticed an error in the programmed flight plan but he was able to fly the usual route into the sound in good visibility. The computer generated plan was checked and the error – a ‘4’ instead of a ‘6’ – amended. Collins and his crew were not told of this ‘minor’ correction but, remarkably, it had the effect of moving his approach to Antarctica 30 miles eastwards.

Gordon Vette had trained Jim Collins and knew him to be a capable and careful pilot. He also appreciated that, although they were flying below cloud the pilots’ visual perception could be affected by the snow covered surface. White-out conditions were not well understood and the accident investigator had paid little heed to both this factor and the flight plan change.

Vette began a campaign for a re-examination of the accident’s cause. The reluctance of the airline to admit any error cost him many friends and later his job. However, it helped to establish a Royal Commission of Inquiry which opened on 7 July 1980 under Mr Justice Mahon, a high court judge. Gordon Vette’s research on white-out conditions was used and the judge even made a flight to Antarctica to find the conditions perfectly reproduced. After no fewer than four time extensions his report was published in April 1981. He concluded that the aircrew were not to blame for the accident and said that some of the counter-evidence he had heard was no more than ‘an orchestrated litany of lies’.

But this was far from the end of the matter. Arguments went on and partisan views generated bad feeling. Even the Prime Minister got involved. Air NZ appealed to the High Court against Judge Mahon’s award of costs and their appeal was upheld although the findings on the cause of the accident were not challenged. Further claims even involved the Privy Council in London. Peter Mahon resigned from the bench and the stress was widely believed to have contributed to his early death.

Gordon Vette published a book about the accident – ‘Impact Erebus’. Vette’s work on the flat-light phenomenon led to the development of forward-looking ground proximity warning systems. His analysis of the human factors, both in accident investigation and accident prevention is used widely used by the International Civil Aviation Organisation. He was made an honorary life member of the NZ Airline Pilots’ Association and was the first to be presented with the Jim Collins Memorial Award for Exceptional Contribution to Flight Safety.

But it took until 1999 for the NZ Parliament finally to give official acknowledgement that Peter Mahon’s findings were the true record of the facts of the impact on Mt Erebus.

There was yet more recognition for Gordon Vette. He was appointed an officer of the NZ Order of Merit and in 2009 received a Presidential Citation from the International Federation of Air Line Pilots.

Vette began a campaign for a re-examination of the accident’s cause. The reluctance of the airline to admit any error cost him many friends and later his job. However, it helped to establish a Royal Commission of Inquiry which opened on 7 July 1980 under Mr Justice Mahon, a high court judge. Gordon Vette’s research on white-out conditions was used and the judge even made a flight to Antarctica to find the conditions perfectly reproduced. After no fewer than four time extensions his report was published in April 1981. He concluded that the aircrew were not to blame for the accident and said that some of the counter-evidence he had heard was no more than ‘an orchestrated litany of lies’.

But this was far from the end of the matter. Arguments went on and partisan views generated bad feeling. Even the Prime Minister got involved. Air NZ appealed to the High Court against Judge Mahon’s award of costs and their appeal was upheld although the findings on the cause of the accident were not challenged. Further claims even involved the Privy Council in London. Peter Mahon resigned from the bench and the stress was widely believed to have contributed to his early death.

Gordon Vette published a book about the accident – ‘Impact Erebus’. Vette’s work on the flat-light phenomenon led to the development of forward-looking ground proximity warning systems. His analysis of the human factors, both in accident investigation and accident prevention is used widely used by the International Civil Aviation Organisation. He was made an honorary life member of the NZ Airline Pilots’ Association and was the first to be presented with the Jim Collins Memorial Award for Exceptional Contribution to Flight Safety.

But it took until 1999 for the NZ Parliament finally to give official acknowledgement that Peter Mahon’s findings were the true record of the facts of the impact on Mt Erebus.

There was yet more recognition for Gordon Vette. He was appointed an officer of the NZ Order of Merit and in 2009 received a Presidential Citation from the International Federation of Air Line Pilots.