Tom Hayhow (Dec 2021)

This is not a name which will conjure up memories for many people unless they are old enough to have been aficionados of 1950s air racing. Those who are will know that Tom Hayhow was a multi-record holder and came to public notice in a brief burst of fame.

Norfolk born - 26 Nov. 1906 – Tom was a marine engineer and Managing Director of a company which broke up and salvaged ships on the River Tees. He came late to flying and got his licence at the age of 41 at the Darlington Aero Club in September 1948. He soon became interested in air racing and comes into our story on 24th May, 1950 when he bought a Miles M-18. Three of this type were built in 1942. Originally with twin open cockpits Tom’s had been refurbished and fitted with a closed cockpit.

The M-18 was in Derby and the next day he went there to collect it and fly it home to Thornaby. It was 6 ‘o clock in the evening before he took off into a murky sky. His direct route would have kept him east of the Pennines but in the poor visibility he lost his bearings and drifted westwards.

Norfolk born - 26 Nov. 1906 – Tom was a marine engineer and Managing Director of a company which broke up and salvaged ships on the River Tees. He came late to flying and got his licence at the age of 41 at the Darlington Aero Club in September 1948. He soon became interested in air racing and comes into our story on 24th May, 1950 when he bought a Miles M-18. Three of this type were built in 1942. Originally with twin open cockpits Tom’s had been refurbished and fitted with a closed cockpit.

The M-18 was in Derby and the next day he went there to collect it and fly it home to Thornaby. It was 6 ‘o clock in the evening before he took off into a murky sky. His direct route would have kept him east of the Pennines but in the poor visibility he lost his bearings and drifted westwards.

The aircraft crashed into cloud covered high ground near Wharfedale. A search party found him two hours later, some distance from the crash, cut and bruised and wearing just one shoe. A night in Skipton Hospital was sufficient for Tom to recover but his aeroplane was a write-off after one day’s ownership. This incident was uncharacteristic for Tom was regarded by his friends as a good pilot.

He was to live up to this reputation with his next aeroplane, an Auster Aiglet. He entered the Daily Express South Coast Air Race, a much publicised event which the Express hoped would outclass the King’s Cup. Certainly it did in prize money – the winner would get £1000. Sixty three hopefuls lined up at the start, ranging in size/power from the diminutive Chilton, via multiple DHs, Miles and Percivals to a Hurricane and Jeffrey Quill’s silver Spitfire 22 i.e. from a modified Ford car engine to a RR Griffin. The mix was leavened by a Swiss Bonanza, Comper Swift, Klemm, French Norécrin, Wicko {flown by Lettice Curtis (ex-ATA) and Neville Duke’s Tomtit. The Mew Gull and Hawk Speed Six (like the Tomtit now Shuttleworth residents) would have joined in but both had suffered ‘landing incidents’ and couldn’t be repaired in time for the start. The 186 mile course ran from Brighton, cross country north east to Whitstable on the north Kent coast then a clockwise beachcoming tour back to Shoreham.

Scratch was Capt Gillman in an Avro Avian. Our hero, Tom, took off 9 mins and 20 secs later. (The Spitfire left 77 minutes after the Avian, had fuel feed problems and landed at Tangmere). From Whitstable, reports began coming in from observers at strategic positions on the course. They noticed that Hugh Kendall, in the little Chilton, seemed to be outwitting the handicappers and was moving up the field. Everyone had the advantage of a tail wind as they scattered the seagulls along the south coast.

Tom was doing well, and overtaking one aircraft after the other. He could see no-one ahead as he flashed across the finishing line and was sure he had won. But Hugh Kendall’s Chilton had taken off one minute before Tom so he had not seen it at all during the race and Kendal crossed the line a full seven minutes before him. So it was Hugh Kendall who collected the fine Trophy and the all important £1000 cheque.

Tom, on the right, doesn’t look too unhappy. He had a £500 cheque in his pocket.

In the after-race chat, the conversation ranged over ways of winning things with your own aeroplane other than racing. What about setting records? Records – in a little Auster! Well, records are set in different categories according to aircraft weight so the competition won’t have an outrageous advantage. The story goes that someone bet Tom that he couldn’t set a record. Whether or not that was the challenge Tom set about planning.

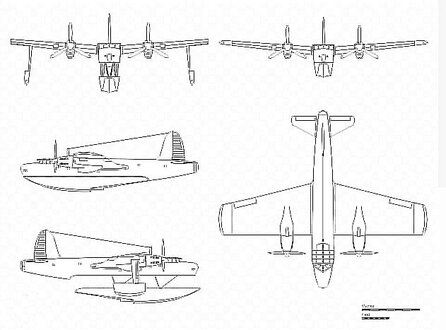

First he changed his aeroplane. He bought G-AMOS, an Auster J5F Aiglet, named, for reasons unknown, Liege Lady. Stressed for aerobatics and with a 130 hp Gypsy Major it could achieve 127 mph. With a few tweaks and modifications it would be ideal for his records and also air racing. He took out the rear seats and had an extra fuel tank installed. He fitted smaller wheels to reduce drag and simplified some of the strut bracing. He had the engine serviced by engineers from De Havilland.

Tom planned to set point-to-point records e.g. London to Paris. Just two flights could set three records, London to Paris, Paris to London and London-Paris-London return. Because it is unlikely that aircraft would be allowed to fly directly over say, Marble Arch and the Eiffel Tower pilots could select other points within 30 kms of the city centres provided the distance between was the same.

Good navigation was critical and, mindful of his Pennine experience Tom decided to install a Decca Navigator. Invented in America but developed in the UK initially for shipping, the system used low frequency radio signals from three or four transmitters to produce a grid of intersecting lines which can be read on a chart to show an accurate position. He organised to have observers ready at every point and prepared to have a hectic Easter weekend.

On Good Friday morning he took off from Elstree for Toussus-le-Noble. Less than four hours later he was back with three London-Paris records in the bag. After a quick lunch it was the turn of London-The Hague to be ticked off. On Easter Saturday he commuted to Brussels and Luxemburg. On Sunday it was Dublin and on Monday Amsterdam. His speeds on these flights varied from as slow as 110 mph to a tailwind assisted 145 mph.

On Good Friday morning he took off from Elstree for Toussus-le-Noble. Less than four hours later he was back with three London-Paris records in the bag. After a quick lunch it was the turn of London-The Hague to be ticked off. On Easter Saturday he commuted to Brussels and Luxemburg. On Sunday it was Dublin and on Monday Amsterdam. His speeds on these flights varied from as slow as 110 mph to a tailwind assisted 145 mph.

He must have gone back to work to top up his bank account (there’s no prize money in record breaking) because his next outing wasn’t until 30th May. Flying from Fairoaks he reached Copenhagen in 5 hrs 13 mins. The return flight took 6 hrs 14 mins at a speed of 98.86 mph. The rules required a minimum speed of 100 mph so that claim was not allowed. The overall out and return however did qualify.

On 7th June he went to Bern in Switzerland. Three more records and on this flight he recorded his shortest time on the ground refuelling, 37 minutes, which is included as part of the total time for the record.

In July 1952, with a remarkable 23 records to his name he had a break and went to the King’s Cup Air Race meeting which was held in Newcastle. Air races are handicapped. Entrants fly a preliminary course to establish their racing speeds then their take-off times in the main race are set – the slowest leaves first and the fastest last. And if all goes to plan, everybody will finish together in a line abreast gaggle. (There is a very narrow margin which disqualifies anyone whose race speed is faster than a smidgen more than their qualifying speed.)

Not everyone can fly in the King’s Cup race. There are qualifying heats and Tom doubled his chances of qualifying by entering two aircraft, his Aiglet and a Tiger Moth.

There were other races. In the Norton-Griffiths Challenge Trophy Tom came a creditable fourth (but out of the prize money) in the Aiglet. He flew the Tiger Moth in the Grosvenor Challenge Cup and although he crossed the finish line in first place, he was disqualified. He was not the only one punished. Two Chilton DW 1s and the Hawker Tomtit of Neville Duke also suffered. These disqualifications were not necessarily because of shaving their speeds. It’s more likely that they cut a corner. The turning points are where races are lost and won. Those who turn closest to the point shorten the race distance and thus can overtake their competitors. Nowadays, everyone carries a little GPS unit. In 1952 the turnpoints were just as rigorously policed by sharp-eyed observers lying on the ground and gazing at a marker directly overhead.

For the King’s Cup, Tom had qualified twice so he could fly either the Aiglet or the Tiger Moth. His dilemma was resolved by another competitor. Fg.Off R W Chandler had come second in the Norton Griffiths Trophy in his Hawk Trainer and such was his joy, he didn’t see the high tension wires he flew through. He had qualified to fly in the King’s Cup and now that his Hawk was de-feathered, Tom offered him the Tiger.

The race itself was something of an anti-climax. 23 pilots flew the 131 mile four lap course, Tom finished in 21st place – only seconds behind the winner, but only two places ahead of last. The Tiger was 13th.

Back to record breaking . . . . At some time early in August – the exact date is not clear – he left Denham and set course for Madrid. There was a certain amount of finger-crossing (over-confidence?) at work because the Decca Navigator did not work in central Spain. Naturally, Tom got lost. This surprised some pilots who know the area where a mountain range clearly points to Cuatro Ventos airport. Maybe Tom didn’t know that. On the last of his petrol he landed on a cart track. There was no fuel at all nearby but he was given a hint where he might get some. He took off again - more crossed fingers - and followed the lead to another cart track near a town. Seven bucket loads of dubious liquid was filtered through his handkerchief. It got him to Madrid where he filled up with genuine fuel. The next day he set off towards Decca-land and managed to tick off another record for the Madrid-London flight.

A few days later, he was off again. A 6 hrs 38 mins flight took him to Stockholm. The return flight took 8hrs 43 mins against a headwind which caused him to land and refuel in the Netherlands. It was still a record at an average speed of 102.19 mph.

Early in 1953, President Tito of Yugoslavia visited London. Tom seized the opportunity and wrote him a diplomatic letter asking permission to land at Belgrade for yet another record. Tito agreed and Tom laid his plans. His usual direct flight would include a landing at Munich for refuelling.

On 10th April Tom left Denham at 06.05. He refuelled at Munich, took off for Belgrade - and disappeared. There were extensive searches, from the air and on the ground. Although Tom had a radio nothing had been heard and nothing could be seen.

It wasn’t until 25th May that some skiers found the crashed Auster in a hollow at 6000ft. It had landed in deep snow and overturned though not extensively damaged. In an eerie echo of his Pennines crash his body with little sign of injury was found some distance from his aircraft. He had been on his way to get help but had been overcome by the freezing conditions.

His 27 records lay in the books until someone inevitably broke them, almost unnoticed. Maybe the record which really counts is that he managed to break so many records in such a short period of time.

On 7th June he went to Bern in Switzerland. Three more records and on this flight he recorded his shortest time on the ground refuelling, 37 minutes, which is included as part of the total time for the record.

In July 1952, with a remarkable 23 records to his name he had a break and went to the King’s Cup Air Race meeting which was held in Newcastle. Air races are handicapped. Entrants fly a preliminary course to establish their racing speeds then their take-off times in the main race are set – the slowest leaves first and the fastest last. And if all goes to plan, everybody will finish together in a line abreast gaggle. (There is a very narrow margin which disqualifies anyone whose race speed is faster than a smidgen more than their qualifying speed.)

Not everyone can fly in the King’s Cup race. There are qualifying heats and Tom doubled his chances of qualifying by entering two aircraft, his Aiglet and a Tiger Moth.

There were other races. In the Norton-Griffiths Challenge Trophy Tom came a creditable fourth (but out of the prize money) in the Aiglet. He flew the Tiger Moth in the Grosvenor Challenge Cup and although he crossed the finish line in first place, he was disqualified. He was not the only one punished. Two Chilton DW 1s and the Hawker Tomtit of Neville Duke also suffered. These disqualifications were not necessarily because of shaving their speeds. It’s more likely that they cut a corner. The turning points are where races are lost and won. Those who turn closest to the point shorten the race distance and thus can overtake their competitors. Nowadays, everyone carries a little GPS unit. In 1952 the turnpoints were just as rigorously policed by sharp-eyed observers lying on the ground and gazing at a marker directly overhead.

For the King’s Cup, Tom had qualified twice so he could fly either the Aiglet or the Tiger Moth. His dilemma was resolved by another competitor. Fg.Off R W Chandler had come second in the Norton Griffiths Trophy in his Hawk Trainer and such was his joy, he didn’t see the high tension wires he flew through. He had qualified to fly in the King’s Cup and now that his Hawk was de-feathered, Tom offered him the Tiger.

The race itself was something of an anti-climax. 23 pilots flew the 131 mile four lap course, Tom finished in 21st place – only seconds behind the winner, but only two places ahead of last. The Tiger was 13th.

Back to record breaking . . . . At some time early in August – the exact date is not clear – he left Denham and set course for Madrid. There was a certain amount of finger-crossing (over-confidence?) at work because the Decca Navigator did not work in central Spain. Naturally, Tom got lost. This surprised some pilots who know the area where a mountain range clearly points to Cuatro Ventos airport. Maybe Tom didn’t know that. On the last of his petrol he landed on a cart track. There was no fuel at all nearby but he was given a hint where he might get some. He took off again - more crossed fingers - and followed the lead to another cart track near a town. Seven bucket loads of dubious liquid was filtered through his handkerchief. It got him to Madrid where he filled up with genuine fuel. The next day he set off towards Decca-land and managed to tick off another record for the Madrid-London flight.

A few days later, he was off again. A 6 hrs 38 mins flight took him to Stockholm. The return flight took 8hrs 43 mins against a headwind which caused him to land and refuel in the Netherlands. It was still a record at an average speed of 102.19 mph.

Early in 1953, President Tito of Yugoslavia visited London. Tom seized the opportunity and wrote him a diplomatic letter asking permission to land at Belgrade for yet another record. Tito agreed and Tom laid his plans. His usual direct flight would include a landing at Munich for refuelling.

On 10th April Tom left Denham at 06.05. He refuelled at Munich, took off for Belgrade - and disappeared. There were extensive searches, from the air and on the ground. Although Tom had a radio nothing had been heard and nothing could be seen.

It wasn’t until 25th May that some skiers found the crashed Auster in a hollow at 6000ft. It had landed in deep snow and overturned though not extensively damaged. In an eerie echo of his Pennines crash his body with little sign of injury was found some distance from his aircraft. He had been on his way to get help but had been overcome by the freezing conditions.

His 27 records lay in the books until someone inevitably broke them, almost unnoticed. Maybe the record which really counts is that he managed to break so many records in such a short period of time.