How the Schneider Trophy was Won (Sept 2018)

The Spirit of Flight is kissing the sea, represented

by Neptune and his three sons.

The Spirit of Flight is kissing the sea, represented

by Neptune and his three sons.

It all started in 1912. Jacques Schneider was an aviation enthusiast who believed that floatplanes were the future of aviation. They could operate from rivers, lakes and the sea and didn’t need expensive airfields. Jacques’ father was a wealthy French industrialist and happily put up the money for the Coupe d’Aviation Maritime Jacques Schneider, an ornate trophy to be awarded annually, with £1000 sterling, to the fastest seaplane.

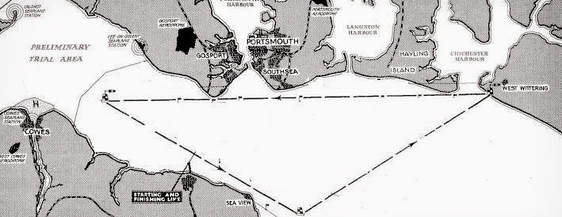

They were to race round a triangular course of 280 kms - later increased to 350kms (217mls) - and the seaplane also had to demonstrate its seaworthiness by travelling at least 500 metres ‘in contact with the sea’. This was later changed to a requirement to sit on the water for six hours then fly the race carrying however much water had leaked into the floats.

In the first race in 1913, which was held at Monaco, there were entries from seven countries. In the event only four French competitors turned up. The race was won by Maurice Prévost in a Deperdussin. His recorded speed was a derisory 45.71 mph. That was because he lost count and landed (alighted?) on the last lap and taxied, rather than flew over the finish line. This disqualified him until he flew another lap 58 minutes later and this delay was added to his race time. In the second year, 1914, there was a last minute entry from Britain and Howard Pixton in the little Sopwith Tabloid trounced the opposition.

After the war, the races resumed in 1919 at Bournemouth. The event was poorly organised and bedevilled by fog. Only one competitor, an Italian seaplane, completed the course. He had missed one of the turning points and so was disqualified. The furious Italians went home with only the satisfaction of hosting the 1920 race. This was held in Venice and the Italians were unopposed, winning at 107.2 mph.

In 1921, there were 16 entries for the Italian team and the three strongest were chosen to fly. A single entry from France was damaged on take off and only one of the Italian entries, a Macchi M.7, completed the race to win at 117.8 mph. Italy had now won two races and the rules laid down that any country winning three races in five years would hold the Trophy ‘in perpetuity’.

After the war, the races resumed in 1919 at Bournemouth. The event was poorly organised and bedevilled by fog. Only one competitor, an Italian seaplane, completed the course. He had missed one of the turning points and so was disqualified. The furious Italians went home with only the satisfaction of hosting the 1920 race. This was held in Venice and the Italians were unopposed, winning at 107.2 mph.

In 1921, there were 16 entries for the Italian team and the three strongest were chosen to fly. A single entry from France was damaged on take off and only one of the Italian entries, a Macchi M.7, completed the race to win at 117.8 mph. Italy had now won two races and the rules laid down that any country winning three races in five years would hold the Trophy ‘in perpetuity’.

The 1922 race was again held at Naples. The home team brought two updated M.17s plus a new Savoia S.17, all biplane flying boats. France had two entries and the British representative was R J Mitchell’s Supermarine Sea Lion II, powered by a 450 hp Napier Lion II. The Italians’ hopes of keeping the Trophy were dashed first, after the Savoia crashed, killing its pilot and then by the Sea Lion’s narrow margin win at 145.72 mph.

Britain hosted the 1923 race at Cowes where the US Navy took first and second places with Curtis biplanes. This was the first military involvement in the races and was seen by some as being slightly unfair, all previous entries having been sponsored by Aero Clubs. The following year, no European nation had an entry ready in time for the race and the Americans sportingly postponed it.

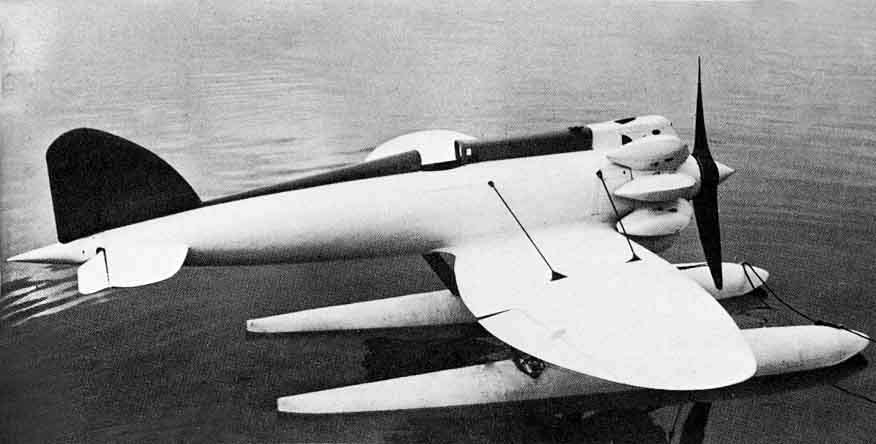

Supermarine S.4

Supermarine S.4

They all assembled at Baltimore in 1925 with aeroplanes specially designed for the race. Supermarine’s S.4 monoplane, which Henri Biard admitted ‘frightened’ him, developed aileron (or maybe wing) flutter in practice and crashed. Happily, Henri suffered only bruises.

So Britain was represented by the Gloster III which came second to the US Army entry, a Curtis R2C-2, flown at a speed of 232.6 mph by a young Lt James Doolittle.

So Britain was represented by the Gloster III which came second to the US Army entry, a Curtis R2C-2, flown at a speed of 232.6 mph by a young Lt James Doolittle.

The Italians felt that they had been ‘hopelessly outclassed’ and set their sights on 1926. Mussolini decided to put weight and money into returning the Trophy to Italy. Their most prominent designer, Mario Castoldi, was commissioned to work with Macchi to produce five machines. In contrast, interest in the race in other countries seemed to be fading. In the US, the cost of developing high speed single-use seaplanes was not seen to bring in any worthwhile business. In Britain, the aircraft manufacturers looked to the government, i.e. the RAF, to bear some, if not all of the cost and Trenchard was firmly against any RAF involvement. From France came a Gallic collective shrug.

In due course, the 1926 race was held at Norfolk, Virginia. The Americans had up-graded their Curtis racers with more powerful engines and were expected to fend off the Italian challenge. There was no entry from Britain. Mitchell’s new S.5 was far from ready.

The home team fared badly. One pilot crashed and was killed on his way to Norfolk. Another crashed the day before the race, but survived the accident. In the event, Lt. George Cuddihy was racing well, even breaking Doolittle’s record, when his fuel pump broke on the last lap in sight of the finish line. Mario de Bernardi won comfortably at 246.5 mph and all Italy celebrated.

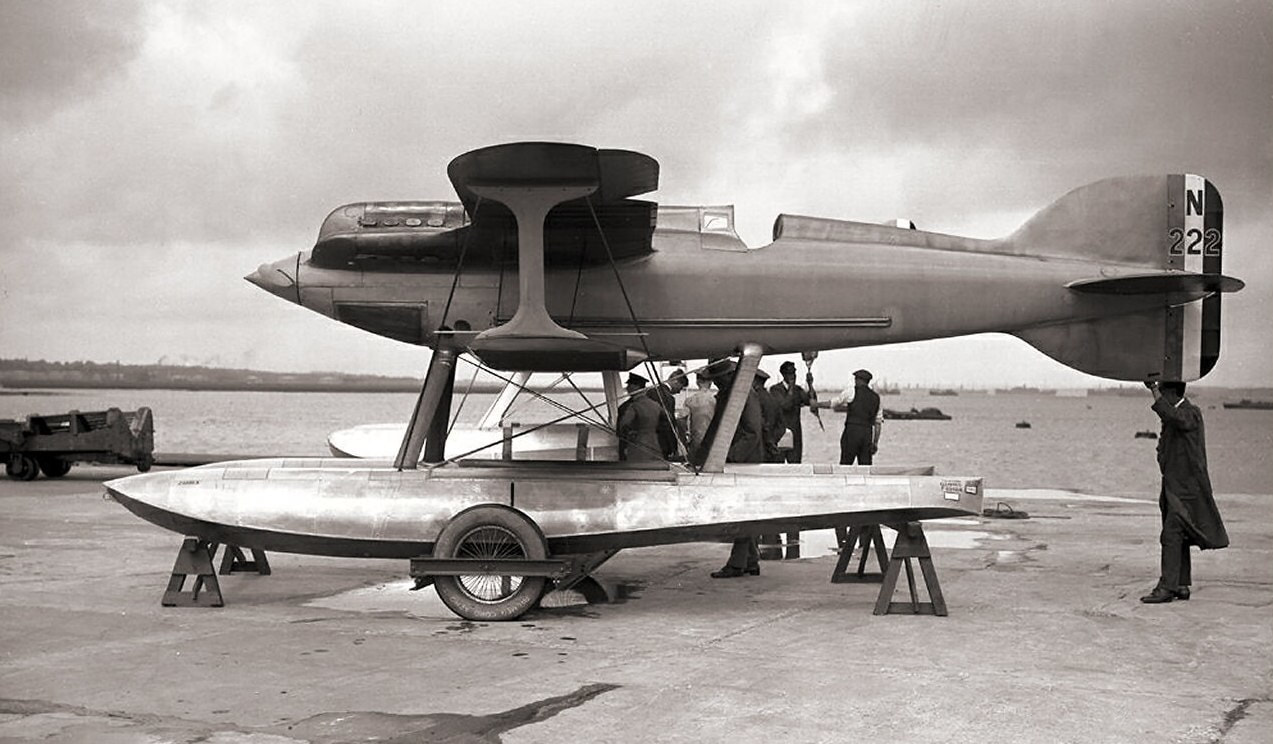

It was back to Venice in 1927. The Italian’s State support had changed the race from a sporting competition between aero clubs to a demonstration of national prestige. Various government committees in London agonised their way to a fudge where money would be found to build machines produced by Supermarine, Gloster and Shorts to be used for the 'advanced training of RAF pilots' in a newly formed High Speed Flight. The US government, of course, had turned its back completely on seaplane racing. This was too much for many American sportsmen who raised $100,000 for a plane to be built by the Kirkham Company, mainly ex-Curtis employees. They planned an advanced biplane powered by a Packard engine which was effectively two 12 cylinder V engines joined together to become a 24 cylinder X monster. It might have worked but they ran out of time. They asked for a delay to sort out their engine problems. The Italians, who were having similar trouble, were inclined to agree to this. The RAF’s attitude was that if they had to be involved they would do the job properly. They insisted on sticking to the rules. The Kirkham-Packard faded into history.

The British team took to Venice three of Mitchell’s S.5s, two Gloster IVs, designed by Henry Folland and one Short Crusader, designed by W G Carter of Hawker. The Crusader was unusual in that it was powered by an air cooled engine, the Bristol Mercury. It flew well but the boosted engine had serious ignition problems. It would suddenly cut out, throwing the pilot forward against his straps. Immediately it would fire normally jerking the pilot back in his set. On arrival in Venice, the Crusader, known in the team as Curious Ada, was assembled and the tanks filled for a run over the full course. After take off the left wing dropped. Correction with the ailerons just seemed to make it worse. The port wing hit the sea at 150 mph and the Crusader broke up. Schofield escaped uninjured. When the wreck was salvaged the aileron cables were found to have been crossed on assembly.

The team chosen for the race were two S.5s, flown by Flt Lts Webster and Worsley with Flt Lt Kinkead in the Gloster. Thousands of spectators were frustrated by the weather. A strong wind caused a 24 hour postponement. The next day seemed little better but gradually improved and the starting gun was fired at 2.29 pm.

Kinkead took off first followed by de Bernardi in the Macchi M.52. Soon all the others were lapping the course. First to fail was the Macchi of Ferrarin, closely following by the con-rod of de Bernardi’s Fiat engine. To match the Italian mood, it began to rain. The Napier Lions of the British team continued to roar although Kinkead detected an unusual vibration. Wisely, he throttled back and landed. There was a crack extending through three quarters of his propeller shaft. Finally, the fuel line in Guazzetti’s Macchi broke leaving just the two S.5s to complete the course. Webster won at an average speed of 281.65 mph, setting a new world speed record. Worsley was close behind.

Kinkead took off first followed by de Bernardi in the Macchi M.52. Soon all the others were lapping the course. First to fail was the Macchi of Ferrarin, closely following by the con-rod of de Bernardi’s Fiat engine. To match the Italian mood, it began to rain. The Napier Lions of the British team continued to roar although Kinkead detected an unusual vibration. Wisely, he throttled back and landed. There was a crack extending through three quarters of his propeller shaft. Finally, the fuel line in Guazzetti’s Macchi broke leaving just the two S.5s to complete the course. Webster won at an average speed of 281.65 mph, setting a new world speed record. Worsley was close behind.

Jacques Schneider attended a meeting in January 1928 when the discussion centred on the races for his Trophy and how it had spurred such a rapid progression in seaplanes’ performance. The annual effort and expenditure were becoming increasingly difficult to justify and it was agreed that it would be better if the races were held every two years. A few months later, Jacques Schneider died and it was regarded as a fitting mark of respect that no race was held in 1928.

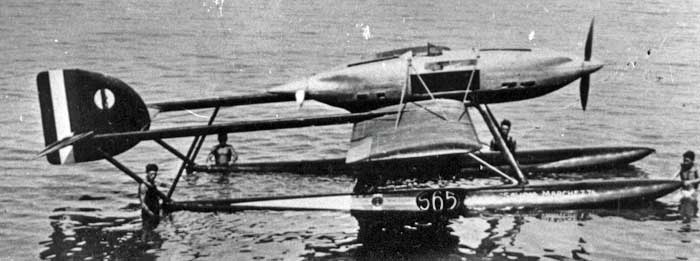

There was no limit on the Italian effort to win the race which was as far ahead as September 1929. The usual Macchi mount was beefed up to take an Isotta-Fraschini Asso engine, a huge V-18 which should produce 1,800 hp. There would be no shortage of engines – no fewer than 27 were ordered. It was a prudent decision: several exploded in testing. Fiat built the C.29, a Macchi look-alike which was different under the skin using a steel tube structure and wings with duralumin spars and skin. Revolutionary designs came from Savoia-Marchetti and Piaggio.

The opposite rotating propellers of the Savoia S65 solved at a stroke the fierce torque which plagued the single engined machines. The Piaggio- Pegna P.7C got rid of floats entirely. The fuselage was built as a water tight boat. The engine drove a small water propeller at the tail, to drive the machine forward until the speed was sufficient for the plane to rise on two hydrofoil surfaces. Then a clutch would engage the main propeller and the PC.7 would take off. A brilliant idea. Unfortunately, the clutch of the water propeller never worked properly.

There was no limit on the Italian effort to win the race which was as far ahead as September 1929. The usual Macchi mount was beefed up to take an Isotta-Fraschini Asso engine, a huge V-18 which should produce 1,800 hp. There would be no shortage of engines – no fewer than 27 were ordered. It was a prudent decision: several exploded in testing. Fiat built the C.29, a Macchi look-alike which was different under the skin using a steel tube structure and wings with duralumin spars and skin. Revolutionary designs came from Savoia-Marchetti and Piaggio.

The opposite rotating propellers of the Savoia S65 solved at a stroke the fierce torque which plagued the single engined machines. The Piaggio- Pegna P.7C got rid of floats entirely. The fuselage was built as a water tight boat. The engine drove a small water propeller at the tail, to drive the machine forward until the speed was sufficient for the plane to rise on two hydrofoil surfaces. Then a clutch would engage the main propeller and the PC.7 would take off. A brilliant idea. Unfortunately, the clutch of the water propeller never worked properly.

France woke from its six year slumber and planned four entries. Progress was slow – and even slower on engine development so pilot training was on single seat fighters. It was just a month before the contest was due to start that one of the pilots died in a crash. Within a few days, France had withdrawn from the contest.

The RAF’s High Speed Flight was reactivated with entirely new personnel and training began using the Gloster IVs from the 1927 race plus Fairey Flycatcher amphibians. Henry Folland began work on the Gloster VI, sticking to the biplane format and Napier Lion engines. Two were delivered a month before the race was due.

R J Mitchell was recommended to use a Rolls Royce engine. From their successful Kestrel Rolls had made the 825 hp Buzzard and that was capable of further development. When approached, RR Managing Director had to be ‘forcefully persuaded’ by the Air Ministry. He felt that the reputation of his engineers would be tainted if they got involved in ‘sordid competition’. Sir Henry Royce himself, by now a semi invalid, was more enthusiastic and sketched out his ideas in the sand on a beach near his home. He expected the engine to produce as much as 1500 hp - even 1800. The S.5 would be too small to carry the heavier engine so Mitchell started work on the S.6 which was to be of all-metal construction with a semi-monocoque fuselage. Both floats contained fuel tanks.

By May, 1929 the RR ‘R’ engine was giving 1,545 hp but only for short periods. To simulate flying conditions the air intake should have been in a 300 mph airstream so a Kestrel was positioned to provide this. Two more Kestrels drove fans, one to cool the crankcase of the ‘R’ and the other to clear the noxious fumes from the test house. Since many tests went on into the night the noise of four aero engines running at full throttle sorely tried the patience of the residents of Derby.

To obviate problems of over-heating, valve distortion and pre-ignition a special fuel additive using benzole and tetra-ethyl lead had been concocted. When it was giving 1850 hp for 100 minutes, the first ‘R’ engine was delivered to Supermarine, seven weeks before the race.

The Italians arrived at Calshot with an imposing array of aeroplanes – two Macchi M 67s, two M.65s (one for practice) and also the Fiat and Savoia machines, not necessarily to fly, just to impress. First there was the water-tightness test, six hours sitting on the water which was carried out overnight. One of the S6s was seen to be listing. Mitchell was dragged from his bed to assess the situation. He decided that the S.6 probably wouldn’t sink. It didn’t and was beached to be quickly repaired next morning.

The RAF’s High Speed Flight was reactivated with entirely new personnel and training began using the Gloster IVs from the 1927 race plus Fairey Flycatcher amphibians. Henry Folland began work on the Gloster VI, sticking to the biplane format and Napier Lion engines. Two were delivered a month before the race was due.

R J Mitchell was recommended to use a Rolls Royce engine. From their successful Kestrel Rolls had made the 825 hp Buzzard and that was capable of further development. When approached, RR Managing Director had to be ‘forcefully persuaded’ by the Air Ministry. He felt that the reputation of his engineers would be tainted if they got involved in ‘sordid competition’. Sir Henry Royce himself, by now a semi invalid, was more enthusiastic and sketched out his ideas in the sand on a beach near his home. He expected the engine to produce as much as 1500 hp - even 1800. The S.5 would be too small to carry the heavier engine so Mitchell started work on the S.6 which was to be of all-metal construction with a semi-monocoque fuselage. Both floats contained fuel tanks.

By May, 1929 the RR ‘R’ engine was giving 1,545 hp but only for short periods. To simulate flying conditions the air intake should have been in a 300 mph airstream so a Kestrel was positioned to provide this. Two more Kestrels drove fans, one to cool the crankcase of the ‘R’ and the other to clear the noxious fumes from the test house. Since many tests went on into the night the noise of four aero engines running at full throttle sorely tried the patience of the residents of Derby.

To obviate problems of over-heating, valve distortion and pre-ignition a special fuel additive using benzole and tetra-ethyl lead had been concocted. When it was giving 1850 hp for 100 minutes, the first ‘R’ engine was delivered to Supermarine, seven weeks before the race.

The Italians arrived at Calshot with an imposing array of aeroplanes – two Macchi M 67s, two M.65s (one for practice) and also the Fiat and Savoia machines, not necessarily to fly, just to impress. First there was the water-tightness test, six hours sitting on the water which was carried out overnight. One of the S6s was seen to be listing. Mitchell was dragged from his bed to assess the situation. He decided that the S.6 probably wouldn’t sink. It didn’t and was beached to be quickly repaired next morning.

A more serious problem surfaced when a set of new sparking plugs was being fitted to Waghorn’s engine the night before the race. A mechanic noticed a little fleck of white metal on one of the electrodes. The Rolls Royce engineering manager realised that it indicated a potential failure in the engine. A complete engine change was not allowed in the rules. The cylinder block could be changed but the RAF had no-one competent to do this. It happened that a group of RR engineers had come down from Derby to watch their engines perform. They were rounded up from various pubs and hotels in Southampton. Although lacking all the equipment that would have made the job easy they cheerfully sobered up and changed the block overnight. In the offending block they found a partially seized piston and a badly scored cylinder.

Waghorn was first to fly and set off aiming 70° to the right of the wind. The torque pushed the left float deep and the wing tip was just clear of the water. As the speed increased the spray cleared enough for him to see where he was going. The controls began to take effect and he was able to ease off the full right rudder he was holding on allowing the nose to turn gently into wind. He timed it well and lifted off cleanly at 100 mph directly into wind.

With all the shipping that had come to see the race, from destroyers down to rowing boats it was not easy to pick out the marker boats at the turns. He used, not full throttle, but enough to keep the temperature gauge at 95°. As he passed the flag-bedecked Ryde Pier at the end of the lap he punched a hole in the paper pinned to a board on the instrument panel. That was his lap counter. Dal Molin was the first Italian to fly and Waghorn was delighted when he gradually caught him up and overtook the Macchi. Six times he punched his lap counter and set off on his final lap. Suddenly, his engine cut out and immediately re-started. Then it began spluttering and Waghorn knew he was running out of fuel. He pulled up to 800 feet hoping he could still finish, even if he was just gliding. It was not to be. The engine stopped and he glided to a landing.

He slumped in the cockpit, overwhelmed by disappointment and self- recrimination. What had he done wrong? When the launch arrived to retrieve the S.6 he couldn’t understand why they were waving and shouting. Then he realised he had simply miscounted and had been flying an extra lap.

Dal Molin clearly was slower than Waghorn. The other Italians flew strongly and were recording some ominously fast laps until Cadringher became disorientated, overcome by exhaust fumes filling the cockpit. Monti, too, was affected by fumes and a smoked up windscreen. Then a broken joint sprayed him with steam and boiling water. He was able to put down safely and was taken to hospital.

Waghorn was first to fly and set off aiming 70° to the right of the wind. The torque pushed the left float deep and the wing tip was just clear of the water. As the speed increased the spray cleared enough for him to see where he was going. The controls began to take effect and he was able to ease off the full right rudder he was holding on allowing the nose to turn gently into wind. He timed it well and lifted off cleanly at 100 mph directly into wind.

With all the shipping that had come to see the race, from destroyers down to rowing boats it was not easy to pick out the marker boats at the turns. He used, not full throttle, but enough to keep the temperature gauge at 95°. As he passed the flag-bedecked Ryde Pier at the end of the lap he punched a hole in the paper pinned to a board on the instrument panel. That was his lap counter. Dal Molin was the first Italian to fly and Waghorn was delighted when he gradually caught him up and overtook the Macchi. Six times he punched his lap counter and set off on his final lap. Suddenly, his engine cut out and immediately re-started. Then it began spluttering and Waghorn knew he was running out of fuel. He pulled up to 800 feet hoping he could still finish, even if he was just gliding. It was not to be. The engine stopped and he glided to a landing.

He slumped in the cockpit, overwhelmed by disappointment and self- recrimination. What had he done wrong? When the launch arrived to retrieve the S.6 he couldn’t understand why they were waving and shouting. Then he realised he had simply miscounted and had been flying an extra lap.

Dal Molin clearly was slower than Waghorn. The other Italians flew strongly and were recording some ominously fast laps until Cadringher became disorientated, overcome by exhaust fumes filling the cockpit. Monti, too, was affected by fumes and a smoked up windscreen. Then a broken joint sprayed him with steam and boiling water. He was able to put down safely and was taken to hospital.

D’Arcy Greig, Waghorn (who has had time to change) and Atcherley.

D’Arcy Greig, Waghorn (who has had time to change) and Atcherley.

D’Arcy Greig completed the course. His S.5 was slower than the S6s but he was there to post what was effectively an insurance time.

Atcherley, however could have won. He would have been second had he not missed a turning point. His goggles had been coated with oily water and he raised them to his forehead briefly to check his position. The slipstream whipped them away and he flew on with head down in the cockpit, squinting out from time to time.

He did achieve record speeds for 50 and 100 kilometres records but his second place went to Dal Molin. Waghorn’s winning speed was 328.64 mph.

Atcherley, however could have won. He would have been second had he not missed a turning point. His goggles had been coated with oily water and he raised them to his forehead briefly to check his position. The slipstream whipped them away and he flew on with head down in the cockpit, squinting out from time to time.

He did achieve record speeds for 50 and 100 kilometres records but his second place went to Dal Molin. Waghorn’s winning speed was 328.64 mph.

At the post-race banquet one of the Italians commented that he thought there might not be a next time for Italy. The cost of taking part is ‘simply staggering’. Ramsey MacDonald, Britain’s new Labour Prime Minister said, in words that were to haunt him ‘We are going to do our level best to win again’.

Three days after the race, in the echoes of the celebrations, Trenchard sent a minute to the Air Minister stressing that he was ‘against this contest. I can see nothing of value in it’. Five days later a Cabinet minute recorded that an RAF team would not again be entered, leaving any participation to the Royal Aero Club. Supermarine and Rolls Royce discussed the possibility of a joint entry but were told that they could not borrow the RAF’s aircraft or pilots again.

Despite these firmly expressed attitudes, the RAF used both the Gloster VI and one of the S.6s to raise the world speed record to 336.3 mph and 357.7 mph.

The argument to compete or not rumbled on through 1930. Persuasive arguments, deputations of MPs to the Prime Ministers had all failed. Decision time for the Royal Aero Club came in January 1931. It was clear that other countries were making preparations. The RAeC had promises amounting to £22,000. How could they possibly raise the estimated £80 - £100,000 to enter a team to achieve the ultimate goal of winning and retaining the Trophy. Then the PM received a telegram which said in part ‘To prevent the Socialist Government being spoilsports Lady Houston will be responsible for all extra expenses . . . ‘. The Chief of Air Staff, Sir John Salmond hurriedly arranged a meeting with Supermarine and Rolls Royce and confirmed that both companies and the RAF (Trenchard had retired in 1929), were willing to enter the contest. The PM was able to make his statement in the House on 29th January to general acclaim.

Three days after the race, in the echoes of the celebrations, Trenchard sent a minute to the Air Minister stressing that he was ‘against this contest. I can see nothing of value in it’. Five days later a Cabinet minute recorded that an RAF team would not again be entered, leaving any participation to the Royal Aero Club. Supermarine and Rolls Royce discussed the possibility of a joint entry but were told that they could not borrow the RAF’s aircraft or pilots again.

Despite these firmly expressed attitudes, the RAF used both the Gloster VI and one of the S.6s to raise the world speed record to 336.3 mph and 357.7 mph.

The argument to compete or not rumbled on through 1930. Persuasive arguments, deputations of MPs to the Prime Ministers had all failed. Decision time for the Royal Aero Club came in January 1931. It was clear that other countries were making preparations. The RAeC had promises amounting to £22,000. How could they possibly raise the estimated £80 - £100,000 to enter a team to achieve the ultimate goal of winning and retaining the Trophy. Then the PM received a telegram which said in part ‘To prevent the Socialist Government being spoilsports Lady Houston will be responsible for all extra expenses . . . ‘. The Chief of Air Staff, Sir John Salmond hurriedly arranged a meeting with Supermarine and Rolls Royce and confirmed that both companies and the RAF (Trenchard had retired in 1929), were willing to enter the contest. The PM was able to make his statement in the House on 29th January to general acclaim.

Lady Houston (apparently it should be pronounced How-ston - not like mission control) was born Fanny Lucy Radmall in Lambeth. She became a chorus girl, known as ‘Poppy’. She was much married, mostly to older wealthy men with sundry titles and in her 40s she was a Baroness. She’d been an active suffragette and used her money generously to help many good causes. Her support for a home for ex-WWI nurses earned her a DBE. Her last marriage was to Sir Robert Houston, an MP and shipping magnate, described as ‘a hard, ruthless, unpleasant bachelor’. He met his match in Lucy who tore up the will in which he left her only £1 million. He died after less than two years marriage and Lucy inherited £5.5 million. A fervent patriot, she hated the Socialist government.

The time to prepare for the race was short. Rolls expected to get another 400 hp from the ‘R’ engine so the S.6 had to be strengthened. A change of rules had done away with the 6 hours on the water and replaced it with a requirement to take off and land fully loaded before starting the race. The stressing need for the fully loaded landing was particularly taxing.

Testing revealed a sensitivity for aileron flutter. It became really serious when one of the S6s experienced tail flutter which damaged the whole rear fuselage. Mitchell fitted balance weights to all control surfaces. Different propellers were tested. Solutions had to be found for a series of problems.

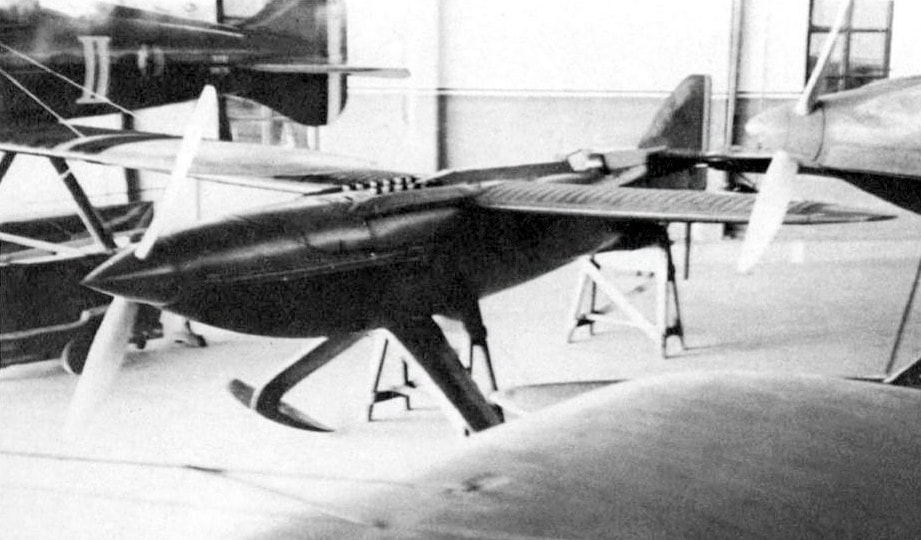

The situation was being paralleled in Italy. They had a new engine, actually two engines, one behind the other. The shaft of the rear engine ran inside the forward engine’s shaft and they drove contra-rotating propellers. It was a great step forward but development was frustratingly slow. Giovanni Monti was testing the new MC.72 when a bearing failed, the propellers touched and the machine dived into the lake, killing Monti. Dal Molin had died too, practising for a speed record. The Italians asked for a postponement. The French echoed the request. They had no suitable aeroplane ready. The RAeC checked the rules which allowed a day to day postponement but not the amount of time needed by the other teams. They turned down the request.

Now it was no longer a race, just a fly over. Flt Lt. John Boothman would fly the race course with Flt Lt Frank Long in reserve, if needed. Then Flt Lt George Stainforth would fly over the 3 kms speed course to set a new record.

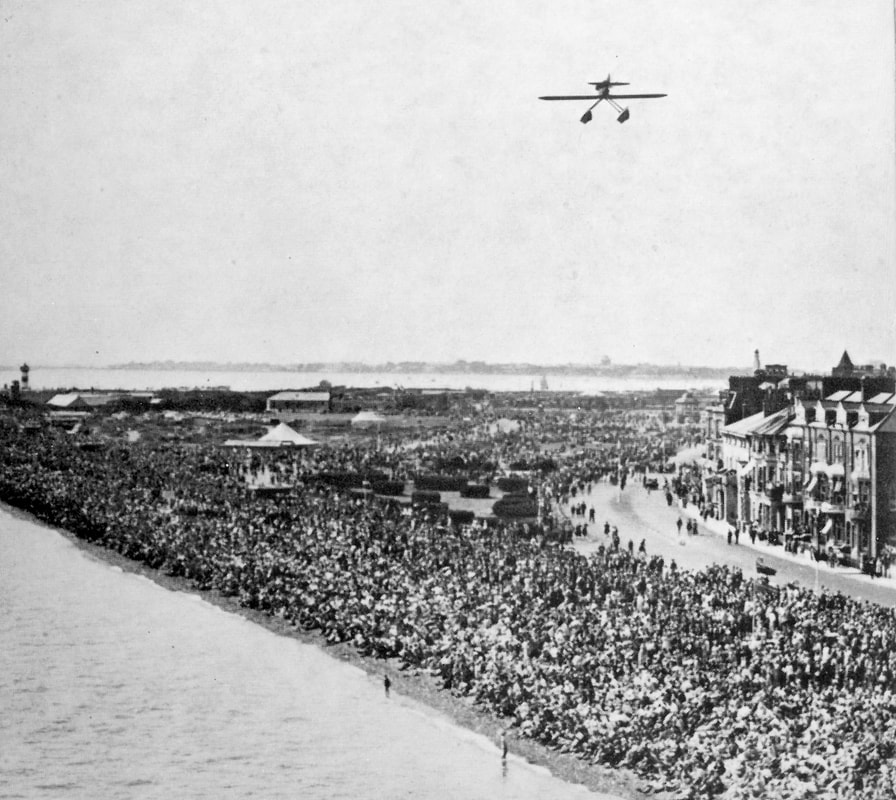

Saturday 12th September came at the end of a fine week although there was a forecast of rain later. It didn’t deter the spectators. Some estimates said a million people turned out. Every vantage point, every beach and hundreds of boats waited for midday, the scheduled start. The pontoons carrying the machines were towed into position. Then it began to rain, the wind blew stronger and the sea roughened. The flying was postponed to the following day.

All went home to dry out and to return in even greater numbers next day. The weather was beautiful with clear visibility. At 1 o’clock the S.6B was launched and Boothman climbed aboard.

Testing revealed a sensitivity for aileron flutter. It became really serious when one of the S6s experienced tail flutter which damaged the whole rear fuselage. Mitchell fitted balance weights to all control surfaces. Different propellers were tested. Solutions had to be found for a series of problems.

The situation was being paralleled in Italy. They had a new engine, actually two engines, one behind the other. The shaft of the rear engine ran inside the forward engine’s shaft and they drove contra-rotating propellers. It was a great step forward but development was frustratingly slow. Giovanni Monti was testing the new MC.72 when a bearing failed, the propellers touched and the machine dived into the lake, killing Monti. Dal Molin had died too, practising for a speed record. The Italians asked for a postponement. The French echoed the request. They had no suitable aeroplane ready. The RAeC checked the rules which allowed a day to day postponement but not the amount of time needed by the other teams. They turned down the request.

Now it was no longer a race, just a fly over. Flt Lt. John Boothman would fly the race course with Flt Lt Frank Long in reserve, if needed. Then Flt Lt George Stainforth would fly over the 3 kms speed course to set a new record.

Saturday 12th September came at the end of a fine week although there was a forecast of rain later. It didn’t deter the spectators. Some estimates said a million people turned out. Every vantage point, every beach and hundreds of boats waited for midday, the scheduled start. The pontoons carrying the machines were towed into position. Then it began to rain, the wind blew stronger and the sea roughened. The flying was postponed to the following day.

All went home to dry out and to return in even greater numbers next day. The weather was beautiful with clear visibility. At 1 o’clock the S.6B was launched and Boothman climbed aboard.

Aiming to the right of the wind he opened the throttle and took off smoothly. After a wide circle he returned for the fully loaded landing. Because of its potential hazard it had deliberately never been tried in testing. This was to be the first and only attempt. He approached at a steady 160 mph expecting the machine to float for over a mile before touch down. It worked perfectly and the touchdown was smooth.

The rules required him to taxi for two minutes and he lined up to take off again before returning to the course. Diving down from 800 feet he flashed over the start line aiming for the first pylon which he rounded in an 80° banked turn. The engine temperature was steady at 88° so he held the throttle wide open although the temperature did vary later. Seven laps were completed at an average speed of 340.08 mph.

The rules required him to taxi for two minutes and he lined up to take off again before returning to the course. Diving down from 800 feet he flashed over the start line aiming for the first pylon which he rounded in an 80° banked turn. The engine temperature was steady at 88° so he held the throttle wide open although the temperature did vary later. Seven laps were completed at an average speed of 340.08 mph.

The eruption of cheering from the crowd blended with hooting and whistling from the assembled fleet of shipping.

Now it was Stainforth’s turn. He flew the straight course four times, twice against the wind and twice with it. The record was comfortably broken at 379.05 mph.

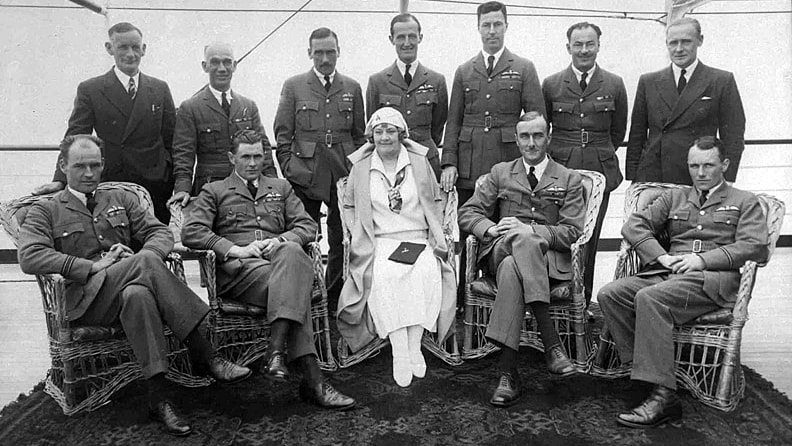

There were nationwide celebrations which were welcome at a time when the economic situation was bleak. Lady Houston held a special party on her yacht for the Schneider Trophy team. That’s R J Mitchell standing on the right.

Now it was Stainforth’s turn. He flew the straight course four times, twice against the wind and twice with it. The record was comfortably broken at 379.05 mph.

There were nationwide celebrations which were welcome at a time when the economic situation was bleak. Lady Houston held a special party on her yacht for the Schneider Trophy team. That’s R J Mitchell standing on the right.

John Boothman and George Stainforth went to Buckingham Palace, each to receive the Air Force Cross. The Trophy found a permanent home in the Royal Aero Club and, by ceasing to be available for competition probably saved the expenditure of millions of future governments’ money.

Finally – back with the Italians. They persevered with the MC.72 and elevated it to the peak of racing seaplanes. Although it killed another pilot it raised the world’s air speed record to 423.5 mph on 10 April 1933 again on 23 October 1934 to 440.7 mph. It then retired, proudly, to where it sits today, in the Italian Air Force Museum.