Might Have Beens (March 12)

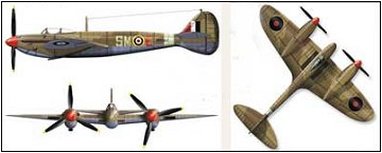

The Spitfire first flew in 1936 and was still in production at the end of the war. It progressed through many mark numbers – as far as Mk 26, with sundry Seafires – multiple versions of Merlins and Griffons, different types of wings and armament, tips elliptical, clipped and pointed. There was even a couple fitted with floats. But what about the twin-engined Spitfire?

Well, you might not have heard of it because of an unfortunate event during the Battle of Britain. Supermarine’s factory was bombed on 26 September, 1940 and the Luftwaffe destroyed the various parts and jigs of the two prototypes under construction, together with the mock-up of the Twin Spit, more correctly called the Supermarine S327. The Air Ministry cancelled the order. All we have left are these photographs of the mock-up.

The design was in response to an AM Specification F18/37. In fact, three proposals were submitted, all using the same wing plan and construction methods of the Spitfire. The Supermarine 327 had an armament of six 20 mm cannon in the wing roots. Also proposed, but rejected, were the Type 324, similar to the 327 but armed with twelve .303 Brownings, six in each wing, and the 325 which had Bristol Taurus engines, fitted as pushers. The maximum speed was estimated at 465 mph. We can get a better idea of what these designs would have looked like from the artwork of Peter Allen, now appearing on the boxes of the model kits which are currently available.

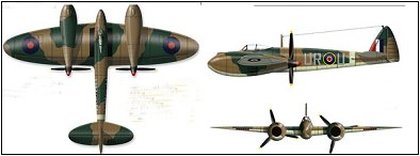

This is the Type 316.

The 317 had a twin-tail.

This is the Type 316.

The 317 had a twin-tail.

There was another casualty of that September air raid. The origins of this go back to an Air Ministry specification issued in1936. B12/36 invited tenders for a 4-engined bomber and Supermarine submitted the Type 316. After agreed changes it became the Type 317 and was accepted as the preferred choice. Two prototypes, fitted with Hercules engines were ordered and construction began. Prototypes of the Short S.29 were also ordered as back-up. Supermarine’s work was destroyed in the raid and the Suffolk, as it would have been named, was cancelled. Its understudy, the S29, designed to the same specification, entered service in 1941 as the Short Stirling.

In the early stages of the war, the Air Ministry became concerned about possible Luftwaffe attacks from high-flying bombers, against which there was no effective defence. Specification F7/41 called for a twin-engined heavy fighter with a pressure cabin. The Vickers Type 432 was accepted and two prototypes were ordered. Powered by two RR Merlin 61 engines it was armed by six 20mm cannon in a ventral blister. The first prototype flew in December 1942 but there were several problems – with ground handling, ailerons and engine installation. There was little indication that the estimated maximum speed of 435 mph would ever be reached. The order was cancelled and the Westland Welkin was ordered instead. In the end, the threat of high altitude bombing never materialised and defence against reconnaissance intruders was effectively handled by the Spitfire Mk VII.

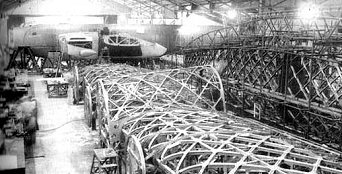

Another Vickers design which got no further than the prototype stage arose from Specification B3/42 for a high-altitude heavy bomber with a pressurised crew compartment and a maximum speed of 345 mph at 31,000 ft. Vickers offered the Windsor, three of which were built incorporating various features. Its defensive armament included barbettes mounted in the rear of each outboard engine nacelle and remotely controlled by the tail gunner in his own pressurised compartment.

The Windsor’s construction was interesting. It used the same geodetic structure as the Wellington and Warwick but their doped Irish linen covering was replaced by a skin made from woven steel wires and thin (1-thou) stainless steel ribbons, doped after assembly with PVC. On the ground, the wing tips drooped but they lifted in flight so the skin on the top of the wing was fitted more tightly than underneath. The proper fitting was tested with a tuning fork.

The three prototypes flew in October 1943, February and July 1944. The first was written off in a forced landing after 34 hours of testing, the others soldiered on until March 1946 when the programme was terminated.

The three prototypes flew in October 1943, February and July 1944. The first was written off in a forced landing after 34 hours of testing, the others soldiered on until March 1946 when the programme was terminated.

An oddity emerged from a project initiated by Winston Churchill. He thought the Army needed an assault glider capable of carrying a tank. L. E. Baynes proposed the Baynes Bat, a 100’ span ‘carrier wing’ to be fitted on top of the tank. A one-third scale model was tested in July 1943 by Robert Kronfeld and, although the wing performed well the project came to naught, partly because the army didn’t have a suitable tank.

The two people mentioned in connection with the Baynes Bat are worthy of a closer look. Leslie Baynes was an aircraft designer who had previously worked for Airco and Short Brothers, where he re-designed the Short Singapore flying boat. In 1931, he built the Scud, a tiny glider of 25’6” span which sold for just £95. Its fin/rudder was inter-changeable with the tailplanes. The Scud 1 (below, left) was followed by the more practical Scud 2 (below, right), with a wingspan of 40 ft. For several years, the Scud 2 held the British gain-of-height record. One was damaged when a hangar roof collapsed on it but was repaired and it still exists. You can see it today in Shuttleworth’s hangar as part of the Collection.

In 1937 Baynes took out a patent for a projected bomber. Its unusual feature was that the twin engines, mounted on the end of the wing, could rotate to provide vertical lift. The Heliplane was never built but in format it pre-dated the US experiments which culminated in the tilt-wing Osprey which came into service with the US Marines in 2007.

Robert Kronfeld was an Austrian who moved to Germany in the early 20s to take up the new sport of gliding. Whilst most of the other glider pilots were sliding to the bottom of the hill, Kronfeld pioneered the use of thermals for soaring and in 1929 won a 5000 mark prize for the first cross-country flight of 100 kms. His demonstration of soaring in England was the spark that led to the formation of the British Gliding Association and in 1931 he won the prize for the first glider flight across the English Channel. When the Nazis banned Jews from flying in 1933 Kronfeld came to England, becoming a British citizen in 1939. He joined the RAF and spent the war as a test pilot, reaching the rank of Squadron Leader and winning the Air Force Cross. Post-war he became Chief Test Pilot for General Aircraft and tested their flying wing design, the GAL 56. In 1949, during stalling trials, it crashed and he was killed. But his name lives on in various trophies which are awarded in gliding competitions.