Louis Arbon Strange, DSO, OBE, MC, DFC & Bar 1891-1966 (Sept/Oct 17)

Raised on his father’s farm in Dorset, Louis became a passionate horseman, following the hounds and competing in point to point events. As soon as he could, aged 17, he joined the Queen’s Own Dorsetshire Yeomanry and greatly enjoyed the training in scouting and shooting. In 1910 a troop of the Yeomanry were asked to assist the police in controlling the crowds expected to attend the Bournemouth Flying Display and Louis was a keen volunteer.

The Frenchman, Leon Morane, took his Bleriot to 4000ft, Cody and Grahame White thrilled the crowds and, sadly, the death of Charles Rolls all emphasised the excitement and danger of aviation. Louis took his first flight the following year and his chief impression was how an aeroplane at just a modest height gave such a wonderful view of the countryside. This came back to him at the Yeomanry exercises in 1913 when a plane flew over his troop. His forcibly expressed opinion that aeroplanes would replace cavalry for reconnaissance caused a fierce argument. It got to the point where Louis placed bets with his colleagues that he would fly over them the following year.

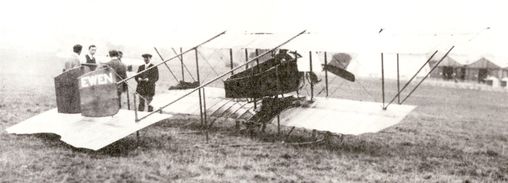

It was an idle boast. How could he find the time to learn to fly when he was so busy on the farm? The opportunity came when he was treating a ewe with foot rot. The animal kicked him in the ribs and he was told to stop working for a time. Enough time to fit in a visit to Hendon where he joined the Ewen School to learn to fly.

The Frenchman, Leon Morane, took his Bleriot to 4000ft, Cody and Grahame White thrilled the crowds and, sadly, the death of Charles Rolls all emphasised the excitement and danger of aviation. Louis took his first flight the following year and his chief impression was how an aeroplane at just a modest height gave such a wonderful view of the countryside. This came back to him at the Yeomanry exercises in 1913 when a plane flew over his troop. His forcibly expressed opinion that aeroplanes would replace cavalry for reconnaissance caused a fierce argument. It got to the point where Louis placed bets with his colleagues that he would fly over them the following year.

It was an idle boast. How could he find the time to learn to fly when he was so busy on the farm? The opportunity came when he was treating a ewe with foot rot. The animal kicked him in the ribs and he was told to stop working for a time. Enough time to fit in a visit to Hendon where he joined the Ewen School to learn to fly.

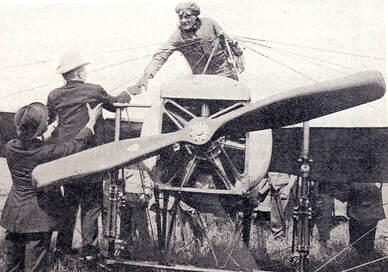

Squeezed into a little tub behind the instructor he was allowed to reached forward to follow the pilot’s movement of the stick to ‘get the feel’ of flying. Then they changed seats and he did ‘rolls’ – taxying. First straights, then figures of eight. Faster rolls followed until the Caudron was briefly airborne.

It took time, fitting these periods of tuition into periods of calm weather, usually very early in the morning. Finally, on 5th August 1913, Louis was officially observed taking two flights, each of 5 kilometres, included figures of eight and successful landings, with the engine stopped, within 50 metres of a chosen spot. The RAeC Certificate, No 575, was the key to a flying career. He applied for a transfer from the Yeomanry to the Royal Flying Corps Reserve. Whilst waiting for that to come through he travelled most weekends to Hendon. He flew the Grahame-White Boxkite and progressed so well that he was offered the chance to take passengers for ‘joyrides’ and even become an instructor. How could he refuse?

fBy the end of the year he was a well established figure at Hendon, flying every type of aeroplane, winning races and indulging in ‘ragtime’ flying – looping, steep turns and dives, side-slips, even spins. In 1914, his reputation as a cross-country racer grew. The prestigious London-Manchester-London race took place in June. One of eight starters, Louis was flying an 80 hp Bleriot. Over 100,000 people waited at Manchester for the fliers to arrive and Louis was first, 35 minutes ahead of his nearest rival. The Lord Mayor of Manchester pushed through the crowd to shake his hand and clambered up, standing on an undercarriage bracing wire. When Louis refuelled, he took off on the return leg. The mayoral bulk had been too much for the bracing wire and it snapped, wrapping rouind and shattering both the propeller and Louis' chance of a gold trophy and £650.

Back at Hendon, he was introduced to the new sport of flour bombing and soon began winning competitions

Back at Hendon, he was introduced to the new sport of flour bombing and soon began winning competitions

Meanwhile, his application for a transfer to the RFC bore fruit. He was interviewed by Major Sefton Brancker and his deputy, Major Trenchard. He was called to join Course No 6 at the Central Flying School at Upavon in May 1914. The CFS, run by Capt Godfrey Paine, was not meant to teach anyone to fly – officers were expected to have paid for their own tuition elsewhere. The only requirement was to fly straight and level to be a platform for effective observation. ‘Stunting’ was expressly forbidden and Louis’ advanced piloting skills were not required.

The official view was reinforced one day after the fuel pipe on Louis’ Bleriot broke and he was sprayed with petrol. He held his breath to avoid being overcome by the fumes. By pushing on full rudder and side slipping, he was able to keep the petrol spray away from his face. He slipped down from 5,000 ft until he was low enough to switch off the engine and land. Capt Paine was watching this and delivered a full flow of invective and purple profanity for breaking the rules and endangering one of His Majesty’s aeroplanes. Towards the end of the course, Louis Strange took part in the annual military exercises. He had great pleasure in flying over the Dorsetshire Yeomanry and landed alongside them to collect the bets placed the previous year.

The outbreak of war came in time to cancel the end of course examinations. Louis was posted to Gosport to join the newly-formed 5 Squadron preparing to move to France. On 14th August four squadrons assembled at Dover. Louis was flying a Farman F-20 which was rather overloaded. His passenger was a bulky Air Mechanic. They both had their own kit and rifle and Louis added an unofficial machine gun. The mechanic had never flown before and fortified himself with a bottle of whisky. On landing at Dover, they ran into an unmarked ditch and broke a longeron. The whisky bottle had gone but the consumed contents meant that the drunken passenger had to be placed under arrest.

The official view was reinforced one day after the fuel pipe on Louis’ Bleriot broke and he was sprayed with petrol. He held his breath to avoid being overcome by the fumes. By pushing on full rudder and side slipping, he was able to keep the petrol spray away from his face. He slipped down from 5,000 ft until he was low enough to switch off the engine and land. Capt Paine was watching this and delivered a full flow of invective and purple profanity for breaking the rules and endangering one of His Majesty’s aeroplanes. Towards the end of the course, Louis Strange took part in the annual military exercises. He had great pleasure in flying over the Dorsetshire Yeomanry and landed alongside them to collect the bets placed the previous year.

The outbreak of war came in time to cancel the end of course examinations. Louis was posted to Gosport to join the newly-formed 5 Squadron preparing to move to France. On 14th August four squadrons assembled at Dover. Louis was flying a Farman F-20 which was rather overloaded. His passenger was a bulky Air Mechanic. They both had their own kit and rifle and Louis added an unofficial machine gun. The mechanic had never flown before and fortified himself with a bottle of whisky. On landing at Dover, they ran into an unmarked ditch and broke a longeron. The whisky bottle had gone but the consumed contents meant that the drunken passenger had to be placed under arrest.

Louis borrowed a Rolls Royce to collect a new longeron from Farnborough. It was 6 a.m. before he had finished fitting it to the Farman. Meanwhile, the mechanic had escaped from the guard tent. It took a trawl of the Dover pubs by the police to find him and Louis finally left for France at midday. After a crossing in poor visibility and showers, they finally arrived at Amiens to cheers from the rest of the RFC contingent and thousands of welcoming Frenchmen. The mechanic stood up, waving another empty whisky bottle and earning himself 56 days No1 Field Punishment.

The squadrons moved to Auberge and watched the regiments of the BEF marching past towards their positions at Mons. There was great excitement when a German Taube was spotted overhead. Louis had devised a mounting with rope and a pulley for his Lewis gun and a strap allowing his observer to stand up safely when shooting. They immediately took off. It was hopeless, of course. The overloaded Farman had no hope of climbing to the Taube’s 5000 ft altitude. When he landed, Louis felt the wrath of the CO and was told to unship the machine gun and engage the enemy ‘properly’, with a rifle.

Within a few days, the retreat from Mons began and the squadron moved back through a series of temporary fields. Sometimes they would return from a patrol to find their field abandoned and found their squadron by spotting one of the lorries, still painted in Bovril red. After the Battle of the Marne, things settled down and the old Farmans were withdrawn, replaced by Avro 504s. Louis fitted his Lewis gun so that the observer, in the front seat, could shoot backwards over the head of the pilot. There were several frustrating and fruitless encounters which helped only by showing how not to get into an effective attacking position. Success finally came on 22nd November, when Louis was flying with Lt. Small.

Within a few days, the retreat from Mons began and the squadron moved back through a series of temporary fields. Sometimes they would return from a patrol to find their field abandoned and found their squadron by spotting one of the lorries, still painted in Bovril red. After the Battle of the Marne, things settled down and the old Farmans were withdrawn, replaced by Avro 504s. Louis fitted his Lewis gun so that the observer, in the front seat, could shoot backwards over the head of the pilot. There were several frustrating and fruitless encounters which helped only by showing how not to get into an effective attacking position. Success finally came on 22nd November, when Louis was flying with Lt. Small.

At 7000 ft over Armentières they met an Aviatik two-seat reconnaissance plane. Louis manoeuvred the Avro so that Freddy Small could fire off a drum of bullets. The German observer defended himself effectively with a Leober pistol and wounded Small in the hand. He was still able to change the drum and they turned again towards the Aviatik.

Small’s next shots were rewarded with a stream of smoke from the Mercedes engine and the Aviatik landed behind the British lines. They dived for home where Louis borrowed a motor-cycle to rushed off and examine his trophy. There was surprisingly little evidence of damage other than a few smashed instruments. He was told that the observer, a Prussian Guards officer, had thought the n.c.o. pilot had landed because he was wounded. When he found him uninjured, he knocked him to the ground and began kicking him viciously before he was restrained.

1915 began for Lt. Strange with promotion to Captain as Flight Commander in 6 Squadron at Poperinghe. Equipped with the BE 2c they were learning to use the new wireless sets to communicate with the artillery. Several machines carried fixed cameras to produce photographic mosaics. When they were ordered to do bombing raids, they had to leave all extra equipment and observers on the ground.

On his second operation from Poperinghe he flew one of several aircraft armed with four French 25 lbs bombs and several hand grenades, ordered to carry out individual attacks on German communications. It was a chance to use the bombing skills he had learned with flour bombs at Hendon. Louis was archied as he crossed the lines and nearly got lost in the cloudy and misty conditions. Spotting the station at Courtrai he dived down to 500 ft. A sentry on the platform fired at him so he threw out a grenade. There were two trains standing in the station and Louis released his bombs on them from 100 ft. Later reports confirmed that the trains had been crowded with troops. Many were killed and the damage caused the station to be blocked for three days. For this, and ‘other acts of gallantry’, Louis was awarded the Military Cross.

The daily routine was spotting for the guns and reconnaissance, suffering the regular attrition caused by increasingly effective German AA fire. Without a machine gun, the weight was just too much for the BE 2c, opportunities for aggression were definitely limited but not entirely absent. One on patrol, Louis and his observer were harassed by an Aviatik armed with a machine gun. The German launched six not very accurate attacks and Louis got fed up dragging the unwieldy BE 2 out of the line of fire. Then he found himself between the Aviatik and the dazzling setting sun. Undetected, he crept close enough for his observer to fire one shot from his rifle. The Aviatik rolled over and spun towards the ground. They were unable to see any wreckage and it would have been unwise to search for it in the inevitable ground fire. A ‘driven down’ claim was satisfaction enough.

The daily routine was spotting for the guns and reconnaissance, suffering the regular attrition caused by increasingly effective German AA fire. Without a machine gun, the weight was just too much for the BE 2c, opportunities for aggression were definitely limited but not entirely absent. One on patrol, Louis and his observer were harassed by an Aviatik armed with a machine gun. The German launched six not very accurate attacks and Louis got fed up dragging the unwieldy BE 2 out of the line of fire. Then he found himself between the Aviatik and the dazzling setting sun. Undetected, he crept close enough for his observer to fire one shot from his rifle. The Aviatik rolled over and spun towards the ground. They were unable to see any wreckage and it would have been unwise to search for it in the inevitable ground fire. A ‘driven down’ claim was satisfaction enough.

In April, a Martinsyde ‘fighter’ was allocated to the squadron. Powered by an 80 hp engine, it had an indifferent performance and was difficult to fly, being rather unstable. Nevertheless, its attractive feature was the forward firing Lewis gun mounted on the top wing to shoot clear of the propeller. On the same day that the Martinsyde was delivered, Louis took it up for his first flight. It could have been his last.

He had spotted an Albatross two-seater and was climbing hard after it. The German observer began firing at long range and a lucky bullet punctured the oil tank. Castor oil leaked out and flooded the floor of the fuselage. The oil ran towards the tail, the nose reared up, the fighter fell into a tail slide and then a spin. Although Louis recovered from the spin he found the Martinsyde impossible to control. The oil sloshed about and the fighter climbed and dived in response. Then the engine stopped. Louis discovered that a sideslip, at the time considered to be a dangerous aerobatic manoeuvre, was the most stable way to descend. He quickly lost the last 3000 ft and somehow forced landed in a hop field, happily, behind the lines.

It was on 8th May, 1915 when Louis was in action again, this time trying to shoot down an Aviatik. They were at 8,500 ft, neither able to climb much higher and exchanging shots with no apparent effect. Louis had emptied the drum of the Lewis gun and he reached up to change it, normally a one-handed job. It seemed to be stuck so he wedged the stick between his knees and used two hands. It still wouldn’t move. To get a better grip he raised himself from his seat. His safety belt ‘must have slipped down’ and his knees lost their grip on the stick. The Martinsyde stalled and flicked into a spin – an inverted spin.

Louis was thrown out of the cockpit, dangling upside down and hanging onto the drum, grateful now that it remained firmly jammed. Its edge was cutting painfully into his fingers. He risked releasing one hand to reach up behind his head to find a strut to grab. The other hand followed to find another strut. His chin was now jammed against the wing. All he could see was the propeller ahead and the revolving town of Menin below. He stopped speculating on where he was going to crash and forced himself to take some action. Repeatedly kicking upwards behind him he at last got one foot inside the cockpit rim. The second followed and finally he was able to kick the stick into a corner of the cockpit.

With a lurch, the Martinsyde recovered from the spin. Louis fell into the cockpit with a bump. He was surprised to find that he could hardly see over the edge of the cockpit. The cushion had fallen out during the spin and, more crucially, his fall had broken the seat. He was sitting on its wreckage which was jamming the controls. Meanwhile, the engine had re-started and they were roaring down at full throttle in a dive towards a much closer Menin.

It was on 8th May, 1915 when Louis was in action again, this time trying to shoot down an Aviatik. They were at 8,500 ft, neither able to climb much higher and exchanging shots with no apparent effect. Louis had emptied the drum of the Lewis gun and he reached up to change it, normally a one-handed job. It seemed to be stuck so he wedged the stick between his knees and used two hands. It still wouldn’t move. To get a better grip he raised himself from his seat. His safety belt ‘must have slipped down’ and his knees lost their grip on the stick. The Martinsyde stalled and flicked into a spin – an inverted spin.

Louis was thrown out of the cockpit, dangling upside down and hanging onto the drum, grateful now that it remained firmly jammed. Its edge was cutting painfully into his fingers. He risked releasing one hand to reach up behind his head to find a strut to grab. The other hand followed to find another strut. His chin was now jammed against the wing. All he could see was the propeller ahead and the revolving town of Menin below. He stopped speculating on where he was going to crash and forced himself to take some action. Repeatedly kicking upwards behind him he at last got one foot inside the cockpit rim. The second followed and finally he was able to kick the stick into a corner of the cockpit.

With a lurch, the Martinsyde recovered from the spin. Louis fell into the cockpit with a bump. He was surprised to find that he could hardly see over the edge of the cockpit. The cushion had fallen out during the spin and, more crucially, his fall had broken the seat. He was sitting on its wreckage which was jamming the controls. Meanwhile, the engine had re-started and they were roaring down at full throttle in a dive towards a much closer Menin.

Louis throttled back, braced himself with his shoulders against the cockpit rim and his feet pressed on the rudder bar. He pulled out parts of the broken seat. This freed the controls and he recovered from the dive with little height to spare. His instruments weren’t working - they had all been damaged by his flailing feet. His strained seatless position was agonising. So stayed low, ignoring the pain in his back and the rifle fire from the Germans he passed over and flew directly back to his airfield at Abeele. After his severe fright and physical exertions Louis went to bed early. He slept for over twelve hours. Even then it was some days before he fully recovered.

The incident provoked an odd reaction from the Squadron CO. He criticised Louis for causing ‘unnecessary damage to the instruments and seat’.

Others have viewed it differently. The unique circumstances of this astonishing escape from death have reverberated over the years. They were recounted as late as 1959 in the ‘Top Spot’ magazine which told the tale in cartoon form, including this illustration.

The incident provoked an odd reaction from the Squadron CO. He criticised Louis for causing ‘unnecessary damage to the instruments and seat’.

Others have viewed it differently. The unique circumstances of this astonishing escape from death have reverberated over the years. They were recounted as late as 1959 in the ‘Top Spot’ magazine which told the tale in cartoon form, including this illustration.

Louis decided to team up with Lanoe Hawker. Hawker had a Bristol Scout, armed with a machine gun which they had fitted, fixed to fire forward at an angle clear of the propeller. The Martinsyde would engage the attention of a German allowing Hawker in the more manoeuvrable Scout to attack.

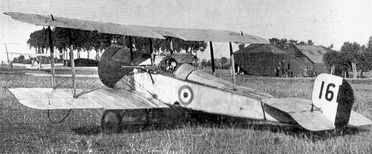

On July 15th, their plan worked well and Hawker shot down an Aviatik. Later in the day, he repeated the feat with a Rumpler. In those early days of aerial combat, this was a unique and extraordinary achievement. Hawker was awarded the Victoria Cross. The photograph shows the very aeroplane, No 1611, that he was flying that day.

In May the BE 2cs were replaced by FE 2bs which were much more capable and could patrol as high as 11,000 ft. Even at that height, Louis’ machine was hit by archie, the oil drained from the engine and it seized. They were well behind the German lines, gliding into a north westerly wind and making little ground as they sank lower.

Capture seemed inevitable and the observer sent messages home, identifying the field where they would land so that the artillery could destroy the FE after they had got clear. As they came neared the ground, they flew into a breeze from the east. This was enough to carry them over the lines to a happy anti-climax, a safe landing.

In August 1915, Louis had been in France for a year. The last of the survivors of the 37 pilots who had crossed the Channel with Louis had been posted home two months before. Louis protested, but his CO ordered him to go. This order was reinforced by Trenchard who wished him well.

He enjoyed his 10 days leave then was delighted to learn that he had been posted as a Flight Commander in 12 Squadron, forming at Netheravon and preparing to go to France. He was not so delighted that they were using BE 2cs, straight from the factory with no extra equipment. It was a hectic four weeks, fitting extra fuel tanks, wireless and bomb racks. Louis added bomb sight and gun mountings of his own design. The Squadron CO, Major Newall, went ahead by sea and Louis led the squadron over the Channel to St Omer.

At the inspection by General Trenchard he saw Louis, and told his ADC to have him sent back to England. Louis kept out of sight and moved to the front with the squadron and ‘got on with the war’. A few days later, a Bristol Scout was delivered. Louis was in the process of fitting his machine gun when Trenchard arrived. ‘Go home at once, Strange’, he boomed. ‘In that machine. Now’. It was a distinctly time-expired Maurice Farman and the wind was blowing at 35 knots. Louis saluted, climbed in and took off. He staggered far enough to land at his old squadron’s airfield where he spent the night before flying home.

He was posted to Gosport, to form the new 23 Squadron and have it ready and operational by 1st January, 1916. It was 21st September when he arrived at Gosport. The Station Commander said he’d never heard of 23 Squadron. ‘Ah’ said Louis. ‘I suppose I’m it’.

He had only the Avro 504 in which he’d arrived. He found an office, a sergeant and an old 50 hp Bleriot. Within a week, he had 44 men, including some pilots to begin training on borrowed Avros. His training was rigorous and relevant to operational conditions and even included night flying. This soon became noticed at RFC HQ and they regularly poached his best pilots for other squadrons. In the midst of all this hectic activity, Louis found time to get married. His best man was Lanoe Hawker.

By the due date, the squadron was ready, although its aeroplanes weren’t. The FE 2bs arrived late in January and the squadron flew off to France. Louis wasn’t with them. He watched them go from a hospital bed. He’d been diagnosed with appendicitis, a swab was left in after the operation and he needed a second operation. In all he spent 14 weeks in hospital which was more effective at keeping him in Home Establishment than Trenchard had been.

He was posted ‘for light duties’ to the Machine Gun School at Hythe. When he arrived the school was training 20 pupils per month. The men were living in tents and there was a shortage of equipment and accommodation for lectures. Stormy weather washed out the tents and small airfield and they had to move operations to Lympne. The Louis Strange philosophy was ‘Do it now’ and officialdom was too slow for him. He requisitioned a hotel for accommodation in the town, commandeered local buses for the daily transport to and from Lympne, used part of The Town Hall for lecture rooms and even took over the local golf course to use a as a rifle range. The repercussions of the complaints rumbled on in the Air Ministry for years.

Within six months the monthly output has risen to 120. The effectiveness of the school triggered the decision to open No 2 Machine Gun School at Turnberry, to be commanded by a newly promoted Lt Col. Strange. This time he was starting with nothing. He scrounged and requisitioned what he could and sent officers to ‘sit on the doorstep’ of government departments to get essential equipment. Soon the school was up and running. To his surprise Louis was sent to Loch Doon in Ayrshire where a third school had been opened. It quickly became evident that the chosen site was inadequate and political influence caused it to be abandoned.

He enjoyed his 10 days leave then was delighted to learn that he had been posted as a Flight Commander in 12 Squadron, forming at Netheravon and preparing to go to France. He was not so delighted that they were using BE 2cs, straight from the factory with no extra equipment. It was a hectic four weeks, fitting extra fuel tanks, wireless and bomb racks. Louis added bomb sight and gun mountings of his own design. The Squadron CO, Major Newall, went ahead by sea and Louis led the squadron over the Channel to St Omer.

At the inspection by General Trenchard he saw Louis, and told his ADC to have him sent back to England. Louis kept out of sight and moved to the front with the squadron and ‘got on with the war’. A few days later, a Bristol Scout was delivered. Louis was in the process of fitting his machine gun when Trenchard arrived. ‘Go home at once, Strange’, he boomed. ‘In that machine. Now’. It was a distinctly time-expired Maurice Farman and the wind was blowing at 35 knots. Louis saluted, climbed in and took off. He staggered far enough to land at his old squadron’s airfield where he spent the night before flying home.

He was posted to Gosport, to form the new 23 Squadron and have it ready and operational by 1st January, 1916. It was 21st September when he arrived at Gosport. The Station Commander said he’d never heard of 23 Squadron. ‘Ah’ said Louis. ‘I suppose I’m it’.

He had only the Avro 504 in which he’d arrived. He found an office, a sergeant and an old 50 hp Bleriot. Within a week, he had 44 men, including some pilots to begin training on borrowed Avros. His training was rigorous and relevant to operational conditions and even included night flying. This soon became noticed at RFC HQ and they regularly poached his best pilots for other squadrons. In the midst of all this hectic activity, Louis found time to get married. His best man was Lanoe Hawker.

By the due date, the squadron was ready, although its aeroplanes weren’t. The FE 2bs arrived late in January and the squadron flew off to France. Louis wasn’t with them. He watched them go from a hospital bed. He’d been diagnosed with appendicitis, a swab was left in after the operation and he needed a second operation. In all he spent 14 weeks in hospital which was more effective at keeping him in Home Establishment than Trenchard had been.

He was posted ‘for light duties’ to the Machine Gun School at Hythe. When he arrived the school was training 20 pupils per month. The men were living in tents and there was a shortage of equipment and accommodation for lectures. Stormy weather washed out the tents and small airfield and they had to move operations to Lympne. The Louis Strange philosophy was ‘Do it now’ and officialdom was too slow for him. He requisitioned a hotel for accommodation in the town, commandeered local buses for the daily transport to and from Lympne, used part of The Town Hall for lecture rooms and even took over the local golf course to use a as a rifle range. The repercussions of the complaints rumbled on in the Air Ministry for years.

Within six months the monthly output has risen to 120. The effectiveness of the school triggered the decision to open No 2 Machine Gun School at Turnberry, to be commanded by a newly promoted Lt Col. Strange. This time he was starting with nothing. He scrounged and requisitioned what he could and sent officers to ‘sit on the doorstep’ of government departments to get essential equipment. Soon the school was up and running. To his surprise Louis was sent to Loch Doon in Ayrshire where a third school had been opened. It quickly became evident that the chosen site was inadequate and political influence caused it to be abandoned.

Louis was not displeased by this because he was posted to be Assistant Commandant of the Central Flying School at Upavon. He arrived in April 1917 – Bloody April, when the RFC were suffering high losses on the Western front – casualty rates were as high as 34%. The policy of ‘no empty seats at the table’ meant that pilots were being rushed to replace casualties with inadequate training. The casualty and accident rates in training were another cause for concern. Most ‘instructors’ were untrained, overworked and resented being there.

A visit to squadrons in France updated Louis’ knowledge of the current state of air fighting and he talked with his old friend, Lanoe Hawker. He was also aware of the methods being introduced by another friend and rebel, Robert Smith-Barry, who was developing revolutionary methods of flying training at Gosport, teaching, rather than avoiding, spins, crosswind landings, and aerobatics.

A visit to squadrons in France updated Louis’ knowledge of the current state of air fighting and he talked with his old friend, Lanoe Hawker. He was also aware of the methods being introduced by another friend and rebel, Robert Smith-Barry, who was developing revolutionary methods of flying training at Gosport, teaching, rather than avoiding, spins, crosswind landings, and aerobatics.

A serious problem at CFS was the high rate of crashes on first solos in the Sopwith Camel. Quite unofficially, he arranged for the fuel tank to be replaced by a smaller one so that a second set of controls could be squeezed in. The mutterings at the Ministry were quelled by the fall in the accident rate. They got the message and an SE 5a was, officially, similarly modified, Louis flew the first one to the CFS. He replaced the worst of the instructors and introduced training for the rest, including some of the best pupils. The evident success of his changes brought another posting, to command No 23 (Training) Wing based at Cranwell. In just two months there he doubled the output of pilots and halved the accident rate.

Throughout his time in England Louis had been pressing for a return to France. Suddenly, on 26th June, 1918, at 24 hours notice, the call came. He was to command the newly formed 80th Wing of the RAF. It was set up as an integrated strike wing and the seven squadrons were equipped with SE-5s, Camels, Bristol Fighters and DH-9s. The tide of battle on the Western front had turned. The last German offensives had been countered and the Allies were preparing their major counter attack. 80th Wing was tasked to attack enemy bases in support of the ground troops.

Instead of individual squadron raids when bomb laden DH 9s would be ‘escorted’ by unladen DH-9s, the escorts would be Bristol Fighters with top cover provided by Camels and SE5s. Careful planning and proper briefings were essential. The first raid was against a German airfield which Louis knew well from his previous time in France. 150 bombs and thousands of rounds of ammunition completely destroyed the airfield, hangars, buildings and supply dumps. All 65 of the wing’s aircraft returned safely.

Throughout his time in England Louis had been pressing for a return to France. Suddenly, on 26th June, 1918, at 24 hours notice, the call came. He was to command the newly formed 80th Wing of the RAF. It was set up as an integrated strike wing and the seven squadrons were equipped with SE-5s, Camels, Bristol Fighters and DH-9s. The tide of battle on the Western front had turned. The last German offensives had been countered and the Allies were preparing their major counter attack. 80th Wing was tasked to attack enemy bases in support of the ground troops.

Instead of individual squadron raids when bomb laden DH 9s would be ‘escorted’ by unladen DH-9s, the escorts would be Bristol Fighters with top cover provided by Camels and SE5s. Careful planning and proper briefings were essential. The first raid was against a German airfield which Louis knew well from his previous time in France. 150 bombs and thousands of rounds of ammunition completely destroyed the airfield, hangars, buildings and supply dumps. All 65 of the wing’s aircraft returned safely.

The next day, a second airfield was raided with equal success. Flying as No 2 to the squadron commander and dropping its four 20 lb bombs on the hangars was the Camel flown by Louis. He regularly flew with the wing, bombing and dog fighting. The effective formations, with squadrons stacked from 2000 to 8000 ft. and carefully planned attacks brought success and saved lives. He drove his men hard but he earned their respect and admiration and they followed willingly. For his outstanding leadership and courage in the last months of the war he was awarded both a DSC and a DFC.

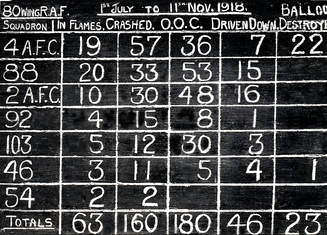

The wing’s scoreboard for the last 4 1/2 months of the war shows their proud record. (AFC are Australian squadrons, OOC means Out of control).

After a number of peace time posts, Louis ended as Commandant of the Flying Wing at the RAF College, Cranwell. The strain of over 1000 hours of flying, more than half in combat, recurring bouts of sciatica and a near death attack of the Spanish flu, had taken their toll and Wg Cdr Strange, DSO, MC, DFC, mentioned in dispatches three times, retired from the RAF in September 1921. He went back to Dorset to recuperate on his father’s farm.

After a number of peace time posts, Louis ended as Commandant of the Flying Wing at the RAF College, Cranwell. The strain of over 1000 hours of flying, more than half in combat, recurring bouts of sciatica and a near death attack of the Spanish flu, had taken their toll and Wg Cdr Strange, DSO, MC, DFC, mentioned in dispatches three times, retired from the RAF in September 1921. He went back to Dorset to recuperate on his father’s farm.

At the farm he rejoined his brother, Ronald, who had been invalided out of the Royal Navy. They set about helping their father to restore and expand his farm. Happily, several years of hard work restored their fitness.

Louis had flown little since his retirement but in 1928 decided to become involved in the development of light aircraft flying. Several clubs had been set up with government assistance and Louis thought that the Isle of Purbeck needed a club. He built a small hangar alongside the football field. This attracted little interest. He took advice from his friend Charles G Grey (influential journalist and commentator and long-time editor of The Aeroplane). He suggested that Louis should contact and possibly join forces with Oliver Simmonds.

Louis had flown little since his retirement but in 1928 decided to become involved in the development of light aircraft flying. Several clubs had been set up with government assistance and Louis thought that the Isle of Purbeck needed a club. He built a small hangar alongside the football field. This attracted little interest. He took advice from his friend Charles G Grey (influential journalist and commentator and long-time editor of The Aeroplane). He suggested that Louis should contact and possibly join forces with Oliver Simmonds.

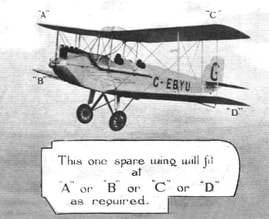

Simmonds had worked for Supermarine and left to design and build his own aeroplane. His big idea was to make components interchangeable. The fin and rudder were the same as the tailplane and elevator; the four main planes were identical. They could even be fitted upside down because the wing section was symmetrical.

The first Spartan was built in Simmonds’ house. The door and windows had to be removed to get it out. It was ready in time for Flt. Lt Webster, of the RAF High Speed Flight, to fly it in the 1928 King’s Cup, which gave useful publicity. It was at this point when Louis Strange joined Simmonds as co-director of the company, to act as test pilot and salesman.

The first Spartan was built in Simmonds’ house. The door and windows had to be removed to get it out. It was ready in time for Flt. Lt Webster, of the RAF High Speed Flight, to fly it in the 1928 King’s Cup, which gave useful publicity. It was at this point when Louis Strange joined Simmonds as co-director of the company, to act as test pilot and salesman.

First, he took the Spartan to Worth Matravers to get his Purbeck Flying Club established. It flew from Croydon to Tempelhof for the Berlin Air Show and Louis gave several demonstrations at Croydon. All this resulted in sufficient orders for production to begin at Southampton. Despite the initial mood of optimism the financial outlook darkened in 1929 and several orders were cancelled. It could have killed off Spartan Aircraft. Louis sought the help of an RFC friend, Harold Balfour, who persuaded Saunders Roe, at Cowes, to incorporate Spartan into Saro. With their advice, the symmetrical wing section was abandoned and production of the newly named Spartan Arrow resumed. A three-seat version was also built – favoured for joy riding.

Louis flew the Arrow in the 1930 King’s Cup and had considerable success in other air races. Any prize money he collected was taken back to the factory and distributed amongst the workers. In the 1932 King’s Cup, as evidence of the popularity of the design, Louis was one of seven pilots who flew Spartan Arrows.

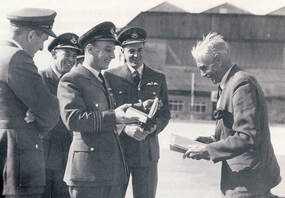

Saro had built a three-engined mailplane designed by Edgar Percival. He realised it had little future and sold the design to Saro. They passed it to Spartan who re-designed it to carry two crew and six passengers. Louis did the test flying and demonstrated it at the 1932 SBAC show. It was well received and Louis was asked to fly the Prince of Wales and later the Lord Mayor of London and the Director of Civil Aviation. He took it on a sales tour of Europe and came home with four orders from Yugoslavia. Later versions of the Cruiser had a more streamlined fuselage and trousered undercarriage.

Louis flew the Arrow in the 1930 King’s Cup and had considerable success in other air races. Any prize money he collected was taken back to the factory and distributed amongst the workers. In the 1932 King’s Cup, as evidence of the popularity of the design, Louis was one of seven pilots who flew Spartan Arrows.

Saro had built a three-engined mailplane designed by Edgar Percival. He realised it had little future and sold the design to Saro. They passed it to Spartan who re-designed it to carry two crew and six passengers. Louis did the test flying and demonstrated it at the 1932 SBAC show. It was well received and Louis was asked to fly the Prince of Wales and later the Lord Mayor of London and the Director of Civil Aviation. He took it on a sales tour of Europe and came home with four orders from Yugoslavia. Later versions of the Cruiser had a more streamlined fuselage and trousered undercarriage.

Spartan started an airline, between Croydon and Cowes, and the Cruiser was used by Northern and Scottish from their Liverpool base. It was used in India, Iraq and Egypt and had the potential for further development.

However Saro were extending their production of flying boats and the Cruiser was something of a distraction. Production ended after only 17 were built. Louis left to find another job.

However Saro were extending their production of flying boats and the Cruiser was something of a distraction. Production ended after only 17 were built. Louis left to find another job.

He was invited to join Willard Whitney Straight, a wealthy American who had lived in England from the age of thirteen. Louis became a director of the Straight Corporation, formed to develop a network of airfields, flying clubs and airlines. Airfields were opened from Plymouth to Inverness. The Corporation organised air shows and races and took over the struggling Western Airways. Louis devised a training programme, used initially for civilians and after 1936 for trainees from the expanding RAF’s newly formed Voluntary Reserve.

Louis joined the RAFVR himself – as a Pilot Officer. When war did break out in 1939 the Straight Corporation was placed under government contract to provide continued training support and air transport, carrying passengers and goods to France. Straight’s operational base was moved to its west country airfields, Plymouth, Weston-super-Mare and Exeter.

Louis was at Exeter when he heard one morning that the Experimental Flight at Farnborough had been given 24 hours’ notice to move to Exeter. He was concerned that the runways were rather short. Within an hour, he had hired a local contractor to uproot trees and hedges and flatten sufficient ground to add 400 yards to the runways. Just in time. The next evening, the Farnborough aircraft flew in. Three weeks later, officials from the Air Ministry Aerodrome Committee arrived to examine the possibility of extending Exeter’s runways. They were rather annoyed to find that they had been forestalled – and without authority.

It was expected by the airlines and charter companies that they would continue to provide an efficient transport service for the RAF. It was not to be. By December, 1939, all their aircraft and bases and been requisitioned and their personnel put into uniform. Louis himself was called up and posted to Kenley for ‘administrative duties’.

He was 49; the age limit for flying duties was 32. He badgered the Air Ministry and was rejected by several selection boards. Eventually, someone senior enough to have known and probably served under Louis in WWI pulled some strings and he was told he could return to General Duties if he could pass the medical. Since he had retired in 1921 on medical grounds that seemed to be a safe concession.

Typically, Louis dodged the examination. He dug out the Air Ministry medical certificate of fitness which had been issued with his Pilot’s ‘B’ Licence in 1928, submitted that and it was accepted. In April 1940 he was posted to 24 Squadron for flying duties.

Louis joined the RAFVR himself – as a Pilot Officer. When war did break out in 1939 the Straight Corporation was placed under government contract to provide continued training support and air transport, carrying passengers and goods to France. Straight’s operational base was moved to its west country airfields, Plymouth, Weston-super-Mare and Exeter.

Louis was at Exeter when he heard one morning that the Experimental Flight at Farnborough had been given 24 hours’ notice to move to Exeter. He was concerned that the runways were rather short. Within an hour, he had hired a local contractor to uproot trees and hedges and flatten sufficient ground to add 400 yards to the runways. Just in time. The next evening, the Farnborough aircraft flew in. Three weeks later, officials from the Air Ministry Aerodrome Committee arrived to examine the possibility of extending Exeter’s runways. They were rather annoyed to find that they had been forestalled – and without authority.

It was expected by the airlines and charter companies that they would continue to provide an efficient transport service for the RAF. It was not to be. By December, 1939, all their aircraft and bases and been requisitioned and their personnel put into uniform. Louis himself was called up and posted to Kenley for ‘administrative duties’.

He was 49; the age limit for flying duties was 32. He badgered the Air Ministry and was rejected by several selection boards. Eventually, someone senior enough to have known and probably served under Louis in WWI pulled some strings and he was told he could return to General Duties if he could pass the medical. Since he had retired in 1921 on medical grounds that seemed to be a safe concession.

Typically, Louis dodged the examination. He dug out the Air Ministry medical certificate of fitness which had been issued with his Pilot’s ‘B’ Licence in 1928, submitted that and it was accepted. In April 1940 he was posted to 24 Squadron for flying duties.

24 was based at Hendon, using a varied collection of requisitioned civilian transport aeroplanes, Rapides, Flamingos, DC-3s, Ensigns – even Italian Savoias. Before he could fly anything, Louis had to be checked out in a Tiger Moth. His ‘instructor’ was an embarrassed young Pilot Officer. At home he kept his father’s RFC ‘wings’ certificate, signed by Major L A Strange. Louis enjoyed being back in a busy flying life. He had to remember to salute most officers he met, even though some quite senior officers he met occasionally slipped back to calling him ‘Sir’.

The German advance into France began on 10th May and soon the situation became chaotic. 24 Sqn were tasked to fly urgently needed supplies of ammunition and rations to France. On 21st May, Louis was scheduled to take a DC-3 with a party of airmen to Merville where he was to act as Aerodrome Control Officer. On take-off, one engine failed and he scrambled into a seat in a DH Dragon. Just after they landed at Merville the airfield was strafed. An Ensign and a Savoia were damaged.

The Hurricane squadron which had been stationed there had hurriedly abandoned the field, leaving several unserviceable aircraft there, some apparently undamaged. They had deliberately been sabotaged simply by cutting the control wires of the variable pitch propellers. Before the Dragon left for Hendon, Louis asked it to come back with a servicing party and some spares to save those Hurricanes which could be flown out.

He and his little group of airmen began work with what they had. They found some telephone cable. Setting the props into fine pitch they attached the cable so that a single pull would change to coarse pitch.

He and his little group of airmen began work with what they had. They found some telephone cable. Setting the props into fine pitch they attached the cable so that a single pull would change to coarse pitch.

As they were working they heard the noise of an air combat overhead. Messerschmitts and Hurricanes whirled about with bursts of gunfire. One of the Hurricanes fell, trailing smoke. The pilot bailed out and it was clear that his parachute would land on the airfield. In a scene which could have been written for a film the pilot was taking off his harness when Louis walked up and said ‘Would you like another Hurricane?’ When 229 Sqn got home to Digby, thinking that Plt Off Tony Linney had been lost, they found that he had landed there before them.

The Germans were getting close to Merville and the Bren gun carriers of the army unit guarding the airfield were ordered to withdraw. They were soon replaced by a group of stragglers led by a DLI sergeant who set up an observation post in a nearby church belfry. A Tiger Moth hopped over the hedge and landed. He was looking for ‘a couple of stray Air Marshals’ who had gone missing. Then a Hurricane flew across the field and dropped a message bag. It was addressed to Louis. 24 Sqn would not be returning. The airmen were to be attached to the nearest British unit and he was to make his own way west and back to England

The Germans were getting close to Merville and the Bren gun carriers of the army unit guarding the airfield were ordered to withdraw. They were soon replaced by a group of stragglers led by a DLI sergeant who set up an observation post in a nearby church belfry. A Tiger Moth hopped over the hedge and landed. He was looking for ‘a couple of stray Air Marshals’ who had gone missing. Then a Hurricane flew across the field and dropped a message bag. It was addressed to Louis. 24 Sqn would not be returning. The airmen were to be attached to the nearest British unit and he was to make his own way west and back to England

A lieutenant drove up on a motor cycle followed by a lorry. He agreed to take the airmen just as the lookout in the church came to report a large group of Germans approaching. Everyone got ready for a smart getaway on the lorry – everyone but Louis. He climbed into one of the semi-serviceable Hurricanes. He had never flown a Hurricane, or anything nearly as powerful. As the engine warmed, he carefully studied the cockpit and the controls.

The take-off was surprisingly quick – and the telephone cable pitch control worked. He kept low until he met tracer fire from some German units so he zoomed up to 8,000 ft. He could see the coast and some RN ships off Boulogne when he ran into a pattern of heavy AA. He turned away and was promptly attacked by a group of six Me 109s.

The leader’s burst of fire missed. Louis pulled back the throttle and the other 109s overshot. Diving down to ground level, he was chased ‘up a village street and down the drive of a chateau’. Twisting along a wooded valley he reached the coast and flew towards the British ships. The Navy's traditional AA fire at anything flying deterred the Messerschmitts and Louis escaped across the Channel to land safely at Manston.

The take-off was surprisingly quick – and the telephone cable pitch control worked. He kept low until he met tracer fire from some German units so he zoomed up to 8,000 ft. He could see the coast and some RN ships off Boulogne when he ran into a pattern of heavy AA. He turned away and was promptly attacked by a group of six Me 109s.

The leader’s burst of fire missed. Louis pulled back the throttle and the other 109s overshot. Diving down to ground level, he was chased ‘up a village street and down the drive of a chateau’. Twisting along a wooded valley he reached the coast and flew towards the British ships. The Navy's traditional AA fire at anything flying deterred the Messerschmitts and Louis escaped across the Channel to land safely at Manston.

A few days later, he flew back to France. 24 Sqn had set up a detachment, initially at Le Bourget, near Paris. The Rapides flew passengers and urgent freight to and from many airfields from Bordeaux to southern England. As the German advance moved west, so the squadron’s base shifted until they were in Nantes, on the shores of the Bay of Biscay. Louis flew the last Rapide out of France, refuelling at Jersey on the way to Hendon. He was welcomed home with the news that, for his Hurricane escapade he had been awarded a bar to the DFC which he won in the first World War. He also received a posting – to Ringway near Manchester ‘for parachuting duties’.

The formation of a Parachute Training School was triggered by the Germans’ use of airborne troops in the invasion of France and Belgium. Churchill personally decreed that there should be a corps of at least 5,000 parachute troops. The group of six puzzled officers posted to Ringway had not been briefed and could get no directions from the Air Ministry. The pressure increased when a Captain and fifty soldiers arrived. Louis borrowed a Leopard Moth and flew to London. He learned that parachute training was the responsibility of the Director of Combined Operations whose harassed deputy happened to be an old friend of Louis’. The rushed plan to form the training school had started badly when the Sqn Ldr chosen to head it had broken his leg. There was no replacement available so Louis was promoted to Squadron Leader on the spot and told that he was the man for the job.

He went to Henlow where the Parachute Development Unit had some static line chutes and an experimental Whitley converted to drop parachutists from a rear platform or, a new innovation, via a hole in the floor. Louis was allowed to address Henlow’s team and call for volunteers to become parachute instructors at Ringway. There were 10 who agreed to come and the next day they went to Bassingbourn to do the first jumps ‘through the hole’.

The formation of a Parachute Training School was triggered by the Germans’ use of airborne troops in the invasion of France and Belgium. Churchill personally decreed that there should be a corps of at least 5,000 parachute troops. The group of six puzzled officers posted to Ringway had not been briefed and could get no directions from the Air Ministry. The pressure increased when a Captain and fifty soldiers arrived. Louis borrowed a Leopard Moth and flew to London. He learned that parachute training was the responsibility of the Director of Combined Operations whose harassed deputy happened to be an old friend of Louis’. The rushed plan to form the training school had started badly when the Sqn Ldr chosen to head it had broken his leg. There was no replacement available so Louis was promoted to Squadron Leader on the spot and told that he was the man for the job.

He went to Henlow where the Parachute Development Unit had some static line chutes and an experimental Whitley converted to drop parachutists from a rear platform or, a new innovation, via a hole in the floor. Louis was allowed to address Henlow’s team and call for volunteers to become parachute instructors at Ringway. There were 10 who agreed to come and the next day they went to Bassingbourn to do the first jumps ‘through the hole’.

Standard aircrew parachutes were modified for static line opening and parachute packers trained. A jumping zone was needed. Nearby was Tatton Park, the home of Lord Egerton, which would be ideal. However, several army units and government departments were competing to use the park. Louis found out that Lord Egerton had been a pioneer aviator. He went to see him to swap tales of ‘the early days’ and came back with authority to use the Park.

On 13th July, 1940 the first jumps into the Park were made by the instructors, jumping ’through the hole’. Naturally, one of the jumpers was Louis, making his first use of a parachute at the age of 49. He didn’t enjoy jumping but didn’t avoid it either. To quote one of the instructors ‘If something went wrong, he was there next morning in the first stick, number one to jump.’

They tested, and abandoned, jumping off the rear platform. As the training got under way and techniques were developed and parachutes and equipment modified to prevent streaming.

The secrecy surrounding their activities and the usual administrative obstacles compounded their problems. There were difficulties in getting personnel and equipment, inconvenient postings and frequent interference. After one fatal accident Major John Rock, the senior Army officer, received a signal from the War Office ordering him to stop parachute training, Louis’ signal from the Air Ministry told him to continue.

They tested, and abandoned, jumping off the rear platform. As the training got under way and techniques were developed and parachutes and equipment modified to prevent streaming.

The secrecy surrounding their activities and the usual administrative obstacles compounded their problems. There were difficulties in getting personnel and equipment, inconvenient postings and frequent interference. After one fatal accident Major John Rock, the senior Army officer, received a signal from the War Office ordering him to stop parachute training, Louis’ signal from the Air Ministry told him to continue.

Louis arranged, officially or otherwise, for the posting in of some of his pre-war ‘flying circus’ friends, all with extensive parachuting experience. He was able to use them to carry out a highly secret operation.

The Dutch Government-in-exile desperately needed to establish a contact in occupied Holland. A naval lieutenant, Lodo van Hamel, had volunteered to go and expected to be landed by boat. This was ruled out because the Germans were actively building coastal defences. Van Hamel was sent to Ringway for a rapid course in parachuting, including a night drop. Louis chose Earl Fielden (ex-Cobham’s Flying Circus) for the operation. They took one of their Whitleys to North Weald. The co-pilot, Louis, didn’t like the fact that his stripped Whitley, with no rear turret, was defenceless. He borrowed a machine gun and cobbled up a mounting in the empty nose turret.

On 23 August, 1940, they took off for Holland. The wind was stronger than forecast and in the cloudy conditions they had difficulty in finding their target. On the approach to the zone a searchlight caught them in its beam and they had to abandon the drop. Three days later, Fielden tried again (Louis had to go back to Ringway). He climbed to 8,000 ft, closed his engines and glided in for an accurate drop before the searchlight was switched on.

The Dutch Government-in-exile desperately needed to establish a contact in occupied Holland. A naval lieutenant, Lodo van Hamel, had volunteered to go and expected to be landed by boat. This was ruled out because the Germans were actively building coastal defences. Van Hamel was sent to Ringway for a rapid course in parachuting, including a night drop. Louis chose Earl Fielden (ex-Cobham’s Flying Circus) for the operation. They took one of their Whitleys to North Weald. The co-pilot, Louis, didn’t like the fact that his stripped Whitley, with no rear turret, was defenceless. He borrowed a machine gun and cobbled up a mounting in the empty nose turret.

On 23 August, 1940, they took off for Holland. The wind was stronger than forecast and in the cloudy conditions they had difficulty in finding their target. On the approach to the zone a searchlight caught them in its beam and they had to abandon the drop. Three days later, Fielden tried again (Louis had to go back to Ringway). He climbed to 8,000 ft, closed his engines and glided in for an accurate drop before the searchlight was switched on.

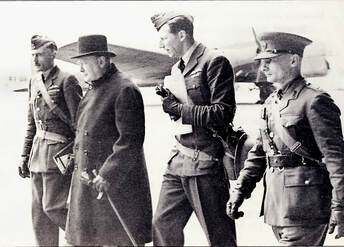

Louis Strange with Churchill, Wg Cdr Sir Nigel Norman and Lt. Col. John Rock

Louis Strange with Churchill, Wg Cdr Sir Nigel Norman and Lt. Col. John Rock

Winston Churchill gave short notice of his visit to Ringway in April 1941. Instead of his 5,000 target fewer than 400 men were on parade. The demonstrated jump was threatened by strong gusty winds but went off well enough. Churchill said little, clearly uinimpressed.

Before he left Louis took him to one side. Later he revealed that he had told the PM privately of the lack of support, even obstruction, of some Air Ministry departments and particularly of the reluctance of unit commanders to release men for what they saw as a vague training scheme. As a result, the Chiefs of Staff felt the wrath of Churchill’s pen. Trainees and equipment began to flow into Ringway.

Before he left Louis took him to one side. Later he revealed that he had told the PM privately of the lack of support, even obstruction, of some Air Ministry departments and particularly of the reluctance of unit commanders to release men for what they saw as a vague training scheme. As a result, the Chiefs of Staff felt the wrath of Churchill’s pen. Trainees and equipment began to flow into Ringway.

Louis was not at Ringway to enjoy it. His unorthodox methods had gained him few friends in high places. Two weeks after the PM’s visit, on 12th May, 1941, a posting notice arrived. His new job, he was told, was top secret. He went to Speke, near Liverpool, to become the Chief Flying Instructor at the MSFU – a newly formed unit. It was so new that the station commander at Speke knew nothing of it. Louis borrowed a Tiger Moth and flew to London.

At Air Ministry he learned that he was to train pilots to be launched by catapult from ships. MSFU was the Merchant Ships Fighter Unit. His own team of fitter, rigger, armourer, pilot and flight direction officer would arrive on 1st June. The RAE at Farnborough were already modifying the standard catapult used on RN cruisers to take the heavier Hurricane. He arranged for a crew of 10 to be posted to Farnborough to learn about the catapult and flew there himself. Some test launches of a Fulmar had been carried out, so he added a new flying experience by taking a launch himself. The 85 ft steel ramp used thirteen rockets to blast the trolley carrying the Fulmar at 3.5G to a speed of 75 mph. A second launch confirmed what he needed to know and he went back to Speke.

The CO of the unit had been appointed. Wg Cdr Moulton-Barrett was an efficient administrator and dealt with the operational procedures produced in relation with the Admiralty, RAF and various civilian organisations. Several 9,000 ton freighters were being modified to be CAMS, Catapult Aircraft Merchant Ships. The first team of six pilots was trained at Farnborough and the first trial launch from a merchant ship, the Empire Rainbow was on 31st May.

The training continued at Speke, now with its own catapult, first tested by Louis, of course. The flight direction officers controlled the launch with flag signals, red for hold, blue for prepare to launch, rotating blue for final preparations. Full throttle, one third flap, one third right rudder to counter swing, head back and elbow jammed to prevent elevator movement and - bang. The Hurricat would sink a little after the launch and needed the gentlest of pressure on the stick to raise the nose. That was the exciting part of the training. It also included a visit to Ringway for a parachute jump and dinghy training in the cold Mersey.

At Air Ministry he learned that he was to train pilots to be launched by catapult from ships. MSFU was the Merchant Ships Fighter Unit. His own team of fitter, rigger, armourer, pilot and flight direction officer would arrive on 1st June. The RAE at Farnborough were already modifying the standard catapult used on RN cruisers to take the heavier Hurricane. He arranged for a crew of 10 to be posted to Farnborough to learn about the catapult and flew there himself. Some test launches of a Fulmar had been carried out, so he added a new flying experience by taking a launch himself. The 85 ft steel ramp used thirteen rockets to blast the trolley carrying the Fulmar at 3.5G to a speed of 75 mph. A second launch confirmed what he needed to know and he went back to Speke.

The CO of the unit had been appointed. Wg Cdr Moulton-Barrett was an efficient administrator and dealt with the operational procedures produced in relation with the Admiralty, RAF and various civilian organisations. Several 9,000 ton freighters were being modified to be CAMS, Catapult Aircraft Merchant Ships. The first team of six pilots was trained at Farnborough and the first trial launch from a merchant ship, the Empire Rainbow was on 31st May.

The training continued at Speke, now with its own catapult, first tested by Louis, of course. The flight direction officers controlled the launch with flag signals, red for hold, blue for prepare to launch, rotating blue for final preparations. Full throttle, one third flap, one third right rudder to counter swing, head back and elbow jammed to prevent elevator movement and - bang. The Hurricat would sink a little after the launch and needed the gentlest of pressure on the stick to raise the nose. That was the exciting part of the training. It also included a visit to Ringway for a parachute jump and dinghy training in the cold Mersey.

Most trainees were RAF volunteers looking for excitement, maybe a run ashore in an American port or even, it was said in the case of Stap-me Stapleton, who made his name in the Battle of Britain, to avoid predatory creditors. One trainee was Tony Linney who had first met Louis when he was offered a Hurricane at Merville. The Navy didn’t bother with volunteers. They posted and trained their own pilots in No 804 ‘Catfighter’ Squadron.

In all, 35 ships were fitted with catapults and in 170 voyages, 12 were sunk. There were 9 combat launches in which 9 German aircraft were destroyed and 1 damaged. One pilot died after rescue from a bail out and 8 Hurricanes were lost (one landed in North Russia after combat). The last MSFU was disbanded in September 1943 by which time sufficient ‘Woolworth’ carriers were in service.

Louis spent a hectic four months at Speke, earning the respect and affection of all who passed through his hands. His worth was also recognised by the Air Officer Commanding at Speke, Air Marshal McCloughry. He had been a Major in the Australian Flying Corps and served in Louis’ 80th Wing in 1918. He offered Louis the command of RAF Valley, a base for four night fighter squadrons.

First he was sent on a week’s leave. It was his first real break in 18 months but not relaxing. He had been keeping a distant eye on his farm and problems there were getting so serious that he decided to sell up. Before things were properly organised his leave ended. He went to RAF Honiley to learn about night fighter operations before taking up his post at Valley.

After a few days there he collapsed from physical and mental exhaustion. Three long months in hospital were followed by enforced convalescence for a further nine months. His farm had been sold and he was invited to Devizes to stay with his old friend, Robert Smith Barry, also convalescing after a Blenheim crash. A move to Warmwell in Dorset gradually restored Louis’ health and he reported back to the Air Ministry. They were surprised to see him. He insisted on a medical examination to prove his fitness and, after a brief period with the recently formed RAF Airfield Construction Companies he was posted as station commander to RAF Hawkinge in December 1942.

In all, 35 ships were fitted with catapults and in 170 voyages, 12 were sunk. There were 9 combat launches in which 9 German aircraft were destroyed and 1 damaged. One pilot died after rescue from a bail out and 8 Hurricanes were lost (one landed in North Russia after combat). The last MSFU was disbanded in September 1943 by which time sufficient ‘Woolworth’ carriers were in service.

Louis spent a hectic four months at Speke, earning the respect and affection of all who passed through his hands. His worth was also recognised by the Air Officer Commanding at Speke, Air Marshal McCloughry. He had been a Major in the Australian Flying Corps and served in Louis’ 80th Wing in 1918. He offered Louis the command of RAF Valley, a base for four night fighter squadrons.

First he was sent on a week’s leave. It was his first real break in 18 months but not relaxing. He had been keeping a distant eye on his farm and problems there were getting so serious that he decided to sell up. Before things were properly organised his leave ended. He went to RAF Honiley to learn about night fighter operations before taking up his post at Valley.

After a few days there he collapsed from physical and mental exhaustion. Three long months in hospital were followed by enforced convalescence for a further nine months. His farm had been sold and he was invited to Devizes to stay with his old friend, Robert Smith Barry, also convalescing after a Blenheim crash. A move to Warmwell in Dorset gradually restored Louis’ health and he reported back to the Air Ministry. They were surprised to see him. He insisted on a medical examination to prove his fitness and, after a brief period with the recently formed RAF Airfield Construction Companies he was posted as station commander to RAF Hawkinge in December 1942.

It could not have been a better posting for him. It was a busy airfield on the front line of the RAF’s confrontation with the enemy. 91 Sqn’s Spitfires were carrying out sweeps over France and 277’s Walruses were on active air sea rescue duties. (Yet again he met Tony Linney, now a Squadron Leader in 277). Louis also controlled ten smaller RAF units in the area.

He launched into his usual 16 hour day, flying when he could, including on a borrowed Spitfire, and getting actively involved in every aspect of the station’s life. The airfield had changed a lot since he had led 12 Sqn from there to France in 1915 but work was still needed. The airfield was on the coast and 400 ft above sea level. Low cloud often reduced visibility. Drainage was poor, the dispersal areas were inadequate and without proper facilities and the runways were too short.

He drew up plans for improvement and submitted them through the proper channels. He also asked for permission to use some ‘secret’ airstrips which he knew had been built on Romney Marsh for diversions when Hawkinge was closed. Permission was immediately refused for this and there was no reaction to his improvement plans.

He launched into his usual 16 hour day, flying when he could, including on a borrowed Spitfire, and getting actively involved in every aspect of the station’s life. The airfield had changed a lot since he had led 12 Sqn from there to France in 1915 but work was still needed. The airfield was on the coast and 400 ft above sea level. Low cloud often reduced visibility. Drainage was poor, the dispersal areas were inadequate and without proper facilities and the runways were too short.

He drew up plans for improvement and submitted them through the proper channels. He also asked for permission to use some ‘secret’ airstrips which he knew had been built on Romney Marsh for diversions when Hawkinge was closed. Permission was immediately refused for this and there was no reaction to his improvement plans.

Another Spitfire overshot a short runway and ran into the hedge. That was enough for Louis to take action. He had quickly built up a good relationship with Lt. Gen Stopforth, the local army commander, giving help with temporary accommodation for his soldiers and providing aircraft to add realism to his exercises. He offered the General exercises for his Royal Engineers. Within a month, the drainage problems had been fixed, the runways extended and the dispersal areas improved. Several field kitchens appeared and a few acres of land had been appropriated.

When all this work came to the notice of the Sector’s Chief Engineer it produced an angry letter reminding Louis that he was just a tenant on the airfield, not its landlord. There was another, more serious, reaction. Louis received notice that he was demoted to Squadron Leader and posted to HQ No 12 Group as supernumerary.

There was no explanation but he knew where the notice had come from. He formally requested an interview with the C-in-C of Fighter Command, Air Marshal Trafford Leigh Mallory. When the interview was finally granted Louis was told that his big mistake had been to ignore proper procedures. Louis apparently countered that his biggest mistake had been as a Lt Colonel in not sending a junior Leigh Mallory back to his regiment after a misdemeanour. (Smith Barry had also been relieved of a command by Leigh Mallory).

Louis went to 12 Group, at Watnall, near Nottingham. In the mess, he was told that the AOC had no time for supernumeraries and he would soon be on his way. Then Jock Matthews, the AOC, walked in. He saw Louis and instinctively stood to attention and said ‘Good morning, sir’. Their last meeting had been in 1918 as Wing Commander and Pilot Officer.

When all this work came to the notice of the Sector’s Chief Engineer it produced an angry letter reminding Louis that he was just a tenant on the airfield, not its landlord. There was another, more serious, reaction. Louis received notice that he was demoted to Squadron Leader and posted to HQ No 12 Group as supernumerary.

There was no explanation but he knew where the notice had come from. He formally requested an interview with the C-in-C of Fighter Command, Air Marshal Trafford Leigh Mallory. When the interview was finally granted Louis was told that his big mistake had been to ignore proper procedures. Louis apparently countered that his biggest mistake had been as a Lt Colonel in not sending a junior Leigh Mallory back to his regiment after a misdemeanour. (Smith Barry had also been relieved of a command by Leigh Mallory).

Louis went to 12 Group, at Watnall, near Nottingham. In the mess, he was told that the AOC had no time for supernumeraries and he would soon be on his way. Then Jock Matthews, the AOC, walked in. He saw Louis and instinctively stood to attention and said ‘Good morning, sir’. Their last meeting had been in 1918 as Wing Commander and Pilot Officer.

Louis became an assistant to Ops Air 1, Gp Capt Brian Thynne (who had been a Spartan owner in the 30s, another useful connection). He was allowed to choose his own number and picked Ops Air 3c which ‘nobody understood so they thought I was something special and left me severely alone’. His job was to visit squadrons, from Northumberland to Norfolk, and sort out any problems. Since he reported directly to Ops Air 1 and the AOC he was in the ideal position to cut through red tape. He was able to offer practical help, passing on effective techniques, particularly in air strikes. He found that the methods he had developed in 80 Wing in WWI were still effective.

He was well received by the squadrons and never seen as an inspector, or ‘trapper’. One comment sums him up. ‘He was very popular and much admired. Meeting him was like touching a bare 220 volt wire. He exuded exuberant energy and a strong, attractive personality’. Louis was flying seventy hours a month and not only in liaison aircraft like the Anson and Proctor. He added Mustang, later marks of Spitfire, Beaufighter, and Mosquito to his log book.

At the end of 1943, Air Marshal Sir Roderick Hill took over from Leigh Mallory as C-in-C Fighter Command. He had served with Louis at Cranwell in 1920 and appreciated his worth. Louis became a Wing Commander again and was posted to 46 Group to train paratroops and Dakota crews. The group was so new that it had no HQ so they assembled initially with 38 Group at Netheravon. There he met many old Ringway friends and he was pleased at the co-operation readily offered by 38. Both the 38 group commander, AVM Hollingsworth and his own AOC, Air Comm. Fiddament had served under Louis, knew his method of working and let him get on with it. He was effectively training a force of parachute and glider-borne troops for the expected invasion.

His attention was mainly directed at the operational procedures for the aircrews, in para-dropping and glider towing, both by day and night. Many of the pilots hadn’t flown a Dakota or any other transport aircraft. At first, Louis borrowed instructors from 38 Group until he had trained his own. The first live drop by an aircraft of 46 Group was on 23 February and Louis was in the Dakota as co-pilot. The five squadrons at Down Ampney, Blakehill Farm and Broadwell were trained and ready by the target date of 1st June.

He received a personal letter from the AOC. ‘All of us know that, but for you, the Group would not have been ready on the day. How well you succeeded was proved by the glowing tributes paid to you when I was at Netheravon recently. I am deeply grateful to you. I would again serve under you, most willingly’.

As a Staff Officer fully briefed on Overlord, Louis was expressly forbidden from any active participation in D-Day, but he was there, in the lead Dakota, as ‘Group Observer, assistant despatcher, cabin boy and steward’. Nine days later, he was in France.

He established his HQ at one of the first airstrips hurriedly constructed 3 miles from Bayeux – and just 3 miles from the front. His job was to set up and control six airstrips, known as Temporary Staging Posts. 46 Group Dakotas would fly in supplies and evacuate wounded. Where he could, he insisted that the Pierced Steel Planking was laid on a bed of straw. It helped in keeping down dust in dry weather and mud in wet. In a cherry orchard, he found a fine horse. He checked with the local mayor that it was not French owned and had been abandoned by the Germans. He used ‘Cherry’, rather than a Jeep, to travel between his TSPs.

It was near one of his airstrips that he met a farmer, Monsieur L’Étrange, and learned something of his Norman ancestry. He was told that the name came to England as early as 1066. One of William’s arrowmakers was a Jean L’Étrange. It was customary for bowmen to burn their names on arrows in case they hit a target worthy of a reward. Local legend held that the arrow which killed King Harold bore the name L’Étrange.

Early in August 2nd Tactical Air Force moved its HQ to Normandy. Its AOC was Air Marshal Coningham, another one of Louis’ 1918 squadron commanders.

After the breakout from the bridgehead, TSPs were moved forward. Keen to get into Paris, Louis took his Anson to the first cleared strip at Orly. That had been allocated to the Americans but Louis was told that he could have Le Bourget once the Germans had left. His initial approach, on the ground, was repulsed by sniper fire. Next day, he managed to get there and found the airfield devastated by Allied bombing and German sabotage. Nevertheless, he ran up the RAF ensign on the damaged control tower. Realising that it would be some days before an airfield construction team would arrive he tracked down the local Maquis and persuaded them to bring in gangs of German prisoners and French collaborators. His TSP was open for operations 24 hours later.

Soon, he had moved to Amiens where he was told that his growing command had been elevated to Wing status – No. 111 Wing. In the move forward, Louis made a personal diversion. In 1918, he had ‘liberated’ the Chateau Lillois, home of the Comte de Meuss and later set up his HQ nearby, making friends with the family. Now, 24 years later, he took his little convoy of staff cars and trucks to the chateau, walked up to the door and rang the bell. The girl who opened the door was the image of her mother, the Comtesse. ‘Hello Jacqueline, he said, ‘Is your mother at home? Tell her Colonel Strange has called’.

When Brussels had been liberated, Louis was based at Evère, the city’s airport, and promoted, temporarily, to Group Captain.