Aleut Alert

Mention ‘Pacific island’ and you will conjure up an image of surf breaking on golden sand, palm trees swaying in a warm breeze and ‘Bali-Hai’ lilting in the background. That couldn’t be further from reality if the Pacific island had been one of the Kuriles or Aleutians, those twin necklaces which link Japan and Alaska via the Russian peninsula of Kamchatka. Far from the main action in the south where US Marines were storming palm-fringed beaches, the 7th Infantry Division’s Pacific island was Unalaska, specifically the US Naval Base at Dutch Harbor. They had just finished their training in desert warfare in California and expected to be going overseas to North Africa but a ‘special order’ had diverted them to Alaska. They trooped ashore in their standard uniforms and looked forward to some hurried exercises - in more appropriate clothing - before their first ever amphibious landing. They were to re-take the islands which had been invaded by the Japanese who were now firmly encamped on American soil.

The invaders had sailed from Japan as part of Admiral Yamamoto’s force that was going to take Midway Island. Invading the Aleutians had always been in the Japanese Grand Strategic plan though some of the senior generals thought that it wouldn’t be necessary. Doolittle’s raid in April had convinced them. They were sure it had been launched from the Aleutians. The invasion was on. Admiral Hosogaya’s two carriers, five cruisers and their supporting ships split from Yamamoto’s main force and turned north.

It was early in the morning of 2nd June 1942 when 17 Japanese planes - bombers and fighters - swept in over Dutch Harbor, bombing and strafing. It would have been more. Half the attackers got lost in dense fog patches. They returned next day in greater strength and did more damage. The Americans had known they were coming. They had cracked the Japanese navy’s code. P-40s from the airfield on Umnak had some success during the raid. Ten Japs were shot down, the Americans lost 11. PBY Catalinas searched for the Jap carriers and B-17s and B-25 stood by to attack. They were not needed. The carriers slipped away in the foul weather.

It was early in the morning of 2nd June 1942 when 17 Japanese planes - bombers and fighters - swept in over Dutch Harbor, bombing and strafing. It would have been more. Half the attackers got lost in dense fog patches. They returned next day in greater strength and did more damage. The Americans had known they were coming. They had cracked the Japanese navy’s code. P-40s from the airfield on Umnak had some success during the raid. Ten Japs were shot down, the Americans lost 11. PBY Catalinas searched for the Jap carriers and B-17s and B-25 stood by to attack. They were not needed. The carriers slipped away in the foul weather.

Further west the Japanese transports approached Attu and Kiska to land their troops. There was no opposition. On Kiska there was a weather station, manned by 19 men and a dog and on Attu 42 native Aleuts and two American employees of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Because they had a radio station, the Americans were questioned as spies. The man was shot, his wife, the Aleuts and the weather men were taken to an internment camp in Japan. The Japanese set about fortifying the islands and, particularly, building airstrips on Kiska.

The Americans too began covering swampy tundra with PSP - pierced steel planking. They landed on unoccupied Adak and Amchitka and established airfields and forward bases from which to launch their planned landings on Kiska and Attu. Throughout the rest of 1942 thousands of troops and a fleet of warships were moved to bases in Alaska in case the Japanese invaded the mainland.

The Americans too began covering swampy tundra with PSP - pierced steel planking. They landed on unoccupied Adak and Amchitka and established airfields and forward bases from which to launch their planned landings on Kiska and Attu. Throughout the rest of 1942 thousands of troops and a fleet of warships were moved to bases in Alaska in case the Japanese invaded the mainland.

There were frequent skirmishes between the opposing forces, some engagements of fire between warships, air raids when the weather permitted - if there wasn’t a dense blanket of fog it always seemed to be blowing a gale, The Americans met a curiosity - a floatplane fighter, the Nakajima Rufe. These were based where the ground wasn’t suitable for airstrips. It was no mean opponent, above the draggy floats was a genuine Zero.

After 18 days close fighting the end came on 29th May. The last Japanese died in a screaming final charge. 2350 enemy bodies were counted, 28 were captured alive. Of the more than 15,000 US troops who landed on Attu, 550 died and 1150 were wounded. Another 2,100 had been taken out of action by disease and non-battle injuries.

They looked forward to Kiska with some trepidation - another 10,000 Japs on a larger island. The Navy fired 330 tons of shells at it. The Air Force dropped 424 tons of bombs on it. Observers said they had seen no movement on the island. Had the Japs retreated to a strongpoint in the hills? More than 34,000 troops, including 5,500 Canadians, were better prepared and equipped than they had been for the Attu assault and on 15th August, in unusually calm weather, the landings began.

Three weeks before the 5,000 Japs who had occupied the island had slipped away so the landings were completely unopposed. There was a bit of friendly fire here and there and the destroyer Amner Read struck a mine so there were only 313 American casualties in the taking of Kiska.

Ever since the first air raids on Dutch Harbor there had been occasional air raids on the American bases and ships, not launched from carriers but from the distant Kuriles. At the northern tip of the Kuriles, all of which were part of Japanese territory, was Paramushiro, the largest of the Kurile islands, heavily fortified with a naval base and five airfields. Alongside was the much smaller of Shimusu, with two airfields and a radar station. From these islands Mitsubishi Betty bombers had raided the Aleutians and launched torpedos against American ships.

They looked forward to Kiska with some trepidation - another 10,000 Japs on a larger island. The Navy fired 330 tons of shells at it. The Air Force dropped 424 tons of bombs on it. Observers said they had seen no movement on the island. Had the Japs retreated to a strongpoint in the hills? More than 34,000 troops, including 5,500 Canadians, were better prepared and equipped than they had been for the Attu assault and on 15th August, in unusually calm weather, the landings began.

Three weeks before the 5,000 Japs who had occupied the island had slipped away so the landings were completely unopposed. There was a bit of friendly fire here and there and the destroyer Amner Read struck a mine so there were only 313 American casualties in the taking of Kiska.

Ever since the first air raids on Dutch Harbor there had been occasional air raids on the American bases and ships, not launched from carriers but from the distant Kuriles. At the northern tip of the Kuriles, all of which were part of Japanese territory, was Paramushiro, the largest of the Kurile islands, heavily fortified with a naval base and five airfields. Alongside was the much smaller of Shimusu, with two airfields and a radar station. From these islands Mitsubishi Betty bombers had raided the Aleutians and launched torpedos against American ships.

Roughly equivalent to the B-25 Mitchell or Heinkel 111 the Betties made their mark early in the war with the sinking of HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse off the coast of Malaya. Lightly built for speed they had no armour for the crew nor self-sealing fuel tanks. Defended by four 7.7 mm guns in nose, turret and waist positions, US fighters soon learned to avoid the sting in the tail, a 20mm cannon. But they found that just one short burst of fire was sufficient to cause the Betty to burst into flame. They called it ‘the flying cigar’ or the ‘one-shot lighter’.

With the Aleutians cleared of Japanese it was time to take the war to Japan - at least to the Kuriles. Two previous attempts to bomb Paramushino had been thwarted by thick cloud cover hiding the island.

On 18th July 18 six B-24 Liberators took off from Attu, each carrying six 500 lbs bombs. They flew west until they sighted the Kamchatka peninsular, which they skirted because, in this part of the world, it was neutral territory. They were pleased to see trees covering the mountainsides - the first trees they had seen for over a year. Crossing the narrow strait which separated Russia and Japan, the first three B-24s dropped their bombs on the airfield at the naval base on Shimsu, the second flight attacked shipping at Paramushiro

There was little opposition, just a few flak bursts. The Liberators took photographs of the Japanese installations, escaping before any Jap fighters took off.

The next raid, with nine B-24s, took place on 11th August. The Japanese had still not set up an effective early warning system although their fighters were ready to take off as soon as they heard the engines overhead. Six Oscars scrambled into the air. The Oscar (Nakajima Ki-43) was fitted with just two guns, mounted in the engine cowling. They were rifle calibre (0.303 in) though occasionally one of the guns was 0.50 in. They caught up with the bombers as they turned away from the target.

The next raid, with nine B-24s, took place on 11th August. The Japanese had still not set up an effective early warning system although their fighters were ready to take off as soon as they heard the engines overhead. Six Oscars scrambled into the air. The Oscar (Nakajima Ki-43) was fitted with just two guns, mounted in the engine cowling. They were rifle calibre (0.303 in) though occasionally one of the guns was 0.50 in. They caught up with the bombers as they turned away from the target.

Attacking from the front, they aimed at the engines and fuel tanks. One of Lt. Pottinger’s engines failed. As he fell back from the formation a second engine lost power. Its supercharger was on fire.

Capt. Lockwood had one engine feathered. The others were now using fuel at a high rate. There were 750 miles to go to get home. The crew began dumping heavy items, even the Norden bombsight overboard. Suddenly, all three running engines spluttered into silence. The engineer frantically turned fuel valves off and on. One after another, the engines came back to life and they were able, after a finely judged flight, to reach home.

One Oscar was late in taking off. The armourers had been working on its guns but could get only one to work. The pilot chased after a Liberator which had become separated from the formation. He turned in for a frontal attack, holding his fire until he was really close to the bomber. The few bullets he fired struck the wings and fuel streamed from the holed tank. Another Oscar attacked and the B-24 blew up. Two parachutes opened below. The escape from death was only a delay. The freezing water would kill them in minutes.

The now rather ragged formation of B-24s was pursued and attacked by the Oscars for 45 minutes. Some gunners claimed kills as they saw a Japanese fighter dive away ‘smoking’ but at last the attacks ceased and the Liberators were allowed to settle down, unhindered, to the long, cold, flight home.

On his own, and not going home was Lt Pottinger. The engine with the burning supercharger soon quit. The two remaining engines couldn’t sustain the bomber in level flight and serious weight-dumping began. Pottinger headed north towards the Kamchatka peninsula. Two Oscars were still taking turns to fire bursts at the limping Liberator. The tail gunner, Sergeant Thomas Ring, shot one down and as it dived away, its engine on fire, the other turned away.

Pottinger had no hope of reaching the Russian airfield at Petropavlosk. Twenty five miles short, he turned in over the coast. The bombardier came out of the nose and he and the gunners braced against a bulkhead. It was a rough landing. A waist gun broke free of its mounting and pitched forward into the gunners, injuring four of them.

It was some time before the Russians turned up and took them to a hospital. One gunner had his spleen removed by a Soviet doctor. He survived by blood donations from the other crew members. Tom Ring’s hip and pelvis were broken. He was lifted, unconscious from the crash and operated on in the hospital. He was recovering well when a blood clot induced a fatal stroke. The Russians and the Americans might have been allies in the war against Germany but here, in the Pacific, the Russians were strictly neutral. All the surviving Americans were interned and sent off on the long journey to internment camp.

Back in Attu, the raid was assessed. Even an optimist couldn’t claim there had been significant damage inflicted in the raid - and there were many, many targets to attack on the two heavily fortified Islands. Despite their bristling defending armament the unescorted bombers had suffered badly. Two were lost, two more were seriously damaged and most of the others had some damage. The next raid would be planned differently.

Capt. Lockwood had one engine feathered. The others were now using fuel at a high rate. There were 750 miles to go to get home. The crew began dumping heavy items, even the Norden bombsight overboard. Suddenly, all three running engines spluttered into silence. The engineer frantically turned fuel valves off and on. One after another, the engines came back to life and they were able, after a finely judged flight, to reach home.

One Oscar was late in taking off. The armourers had been working on its guns but could get only one to work. The pilot chased after a Liberator which had become separated from the formation. He turned in for a frontal attack, holding his fire until he was really close to the bomber. The few bullets he fired struck the wings and fuel streamed from the holed tank. Another Oscar attacked and the B-24 blew up. Two parachutes opened below. The escape from death was only a delay. The freezing water would kill them in minutes.

The now rather ragged formation of B-24s was pursued and attacked by the Oscars for 45 minutes. Some gunners claimed kills as they saw a Japanese fighter dive away ‘smoking’ but at last the attacks ceased and the Liberators were allowed to settle down, unhindered, to the long, cold, flight home.

On his own, and not going home was Lt Pottinger. The engine with the burning supercharger soon quit. The two remaining engines couldn’t sustain the bomber in level flight and serious weight-dumping began. Pottinger headed north towards the Kamchatka peninsula. Two Oscars were still taking turns to fire bursts at the limping Liberator. The tail gunner, Sergeant Thomas Ring, shot one down and as it dived away, its engine on fire, the other turned away.

Pottinger had no hope of reaching the Russian airfield at Petropavlosk. Twenty five miles short, he turned in over the coast. The bombardier came out of the nose and he and the gunners braced against a bulkhead. It was a rough landing. A waist gun broke free of its mounting and pitched forward into the gunners, injuring four of them.

It was some time before the Russians turned up and took them to a hospital. One gunner had his spleen removed by a Soviet doctor. He survived by blood donations from the other crew members. Tom Ring’s hip and pelvis were broken. He was lifted, unconscious from the crash and operated on in the hospital. He was recovering well when a blood clot induced a fatal stroke. The Russians and the Americans might have been allies in the war against Germany but here, in the Pacific, the Russians were strictly neutral. All the surviving Americans were interned and sent off on the long journey to internment camp.

Back in Attu, the raid was assessed. Even an optimist couldn’t claim there had been significant damage inflicted in the raid - and there were many, many targets to attack on the two heavily fortified Islands. Despite their bristling defending armament the unescorted bombers had suffered badly. Two were lost, two more were seriously damaged and most of the others had some damage. The next raid would be planned differently.

In the Kuriles, the Japanese were strengthening their defences. All the troops from Kiska were taken to an isolated base. (Actually they were allowed no contact with any other Japanese to prevent the news of the defeat - i.e. the evacuation of Kiska - spreading to the general population).

More airstrips for fighters were constructed. Hundreds of anti-aircraft guns, many of larger calibre which could reach the highest flying attackers. Two more of the new radar units arrived and, presumably in case the scientists’ new toy didn’t work, they even posted in a unit equipped with sound locators.

The Japanese navy, too, increased their presence on Paramushiro, the base of their most northerly fleet. Every extra warship was a formidable anti-aircraft battery.

More airstrips for fighters were constructed. Hundreds of anti-aircraft guns, many of larger calibre which could reach the highest flying attackers. Two more of the new radar units arrived and, presumably in case the scientists’ new toy didn’t work, they even posted in a unit equipped with sound locators.

The Japanese navy, too, increased their presence on Paramushiro, the base of their most northerly fleet. Every extra warship was a formidable anti-aircraft battery.

Exactly one month after their previous raid eight B-24s and twelve-25s took off before dawn for another attack on the Japanese islands. The plan was for the Liberators to bomb the naval base from high altitude, then for the Mitchells to come in at low level and seek ‘targets of opportunity’ in the shipping in the harbour. They were briefed that, if they had to land in Russia they would claim that they were on a navigation training exercise. This might go some way in not infringing Russia’s neutral status.

The Liberators, flying through a carpet of flak bursts, were able to drop their bombs before a swarm of Oscars and Zeros arrived. They flew on ahead, turned and attacked from the glare of the early morning sun. The faster fighters dived away after their attack The slower Rufes turned tightly and circled in and around the Liberators, shooting from every angle. The lead Liberator lost an engine, a second stopped, its prop windmilling. It dived down, the pilot trying to ditch. As it hit the sea, the turret gunner was still shooting at the Japs. The tail broke off and some survivors were seen swimming in the icy water. A second Liberator went down and circled the swimmers, trying to prevent them from being strafed. That Lib was hit by a cannon shell which exploded on the cockpit and the splinters of Plexiglass Injured everyone inside. The engineer and radioman came forward and lifted the pilots from their seats. They took over the controls - and with occasional advice from the wounded pilot managed to fly the Lib home and land it safely.

The B-25s found no shortage of targets when they attacked through an ‘unbelievable wall of flak’. Waiting for them were the fighters - ‘too many to count’ and three Mitchells were immediately shot down. All the others were damaged, five too badly to attempt to fly home. They followed two B-24s who were heading for Kamchatka. {Another damaged B-25 did fly home but crashed on landing killing half the crew.} One of the B-25s hoping to reach a Russian airfield was seen to be on fire. It went down and crashed in the sea. Another flew over a Russian naval base. They sent up flak at it - but missed.

On the disastrous US Air Force raid of 11th September (1943) twenty planes had been on the raid. Twelve were lost. It was the last daylight raid that the US 11th Air Force would make on the Kurile Islands. The US Navy, on the other hand, reasoned that they had more suitable equipment and could do a better job.

The B-25s found no shortage of targets when they attacked through an ‘unbelievable wall of flak’. Waiting for them were the fighters - ‘too many to count’ and three Mitchells were immediately shot down. All the others were damaged, five too badly to attempt to fly home. They followed two B-24s who were heading for Kamchatka. {Another damaged B-25 did fly home but crashed on landing killing half the crew.} One of the B-25s hoping to reach a Russian airfield was seen to be on fire. It went down and crashed in the sea. Another flew over a Russian naval base. They sent up flak at it - but missed.

On the disastrous US Air Force raid of 11th September (1943) twenty planes had been on the raid. Twelve were lost. It was the last daylight raid that the US 11th Air Force would make on the Kurile Islands. The US Navy, on the other hand, reasoned that they had more suitable equipment and could do a better job.

Based on Amchatka was VB-136, a squadron of Lockheed PV-1 Ventura reconnaissance bombers. With the PBY Catalinas, they had been patrolling the seas to detect any Japanese shipping. They had been occasionally, in rare moments of excitement, attacking them. They were coming to the end of their tour of duty and looking forward to being relieved of the boredom of those long overwater flights in the bleak Alaskan weather.

But the date of their relief was put back and they were ordered to move to the over-crowed island of Attu, where a new airstrip had been built.. Attu was the Aleutian island closest to the Japanese bases on the Kuriles and - just - within range of the PV-1s. They were not to carry out any offensive raids on the Japs from their new base. The arrival, finally, of VB139 allowed VB-136 to fly back to the States in time to enjoy Christmas, 1943 ‘at home’.

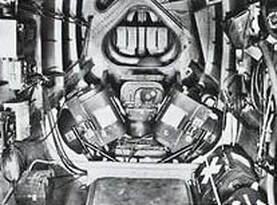

VB-139’s aeroplanes had been much modified. The reconnaissance part of their duties was enhanced by the latest cameras fitted in the nose. These reacted automatically to the flash of million candle power photo-flash bombs which activated the light sensitive trigger on the camera. Other vertical and oblique cameras were in the narrow tail section.

Another extra crew member was a navigator, a function previously handled by the co-pilot. The co-pilot could now live up to his name. The already cluttered instrument panel had another set of flying instruments added in front of him and he had a duplicate set of controls. With a radioman to handle communications and a gunner in the twin 0.50 turret the crew was now up to six. Needing no modification was one of the Ventura’s best features, its 2000 hp P&W R2800 engines. They gave the PV-1s an astonishing top speed of 322 mph, more than enough to get away from most of the Japanese fighters.

The crews trained hard in a series of long flights, carrying out dummy missions and compiling photographic coverage of the Aleutians and other isolated islands in the Bering Sea. It was on one of these flights that they had occasion to use the Direction Finding radio which had been installed at their base on Attu. Returning from a flight from one of those distant islands one crew had become hopelessly lost in the foul January weather. A last minute call that they were preparing to ditch was detected and they were given a course to steer. To everyone’s relief, they got home, landing ‘on fumes’.

The naval contingent on Attu was led by the ‘fire-eating’ Commander Geddes, who went to great lengths to ensure that his men were trained properly - and housed properly. He ‘obtained’ sufficient Quonset huts to ensure that every officer, six to a hut, had his own room. Another hut was a bar where they could relax, there was a theatre where they could enjoy shows and movies and a gym, where they could exercise.

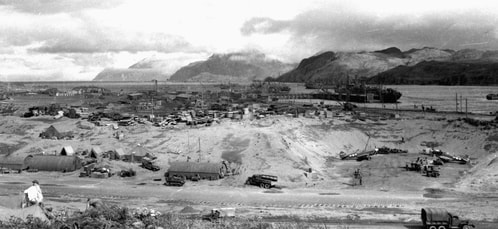

He built a headquarters which overlooked the airstrip at (rather ominously named} Murder Point, which opened into Massacre Bay. The HQ was sometimes referred to as ‘The Palace’, sometimes as ‘Sweat Hill’, a reaction to the men’s response to orders issued from there. The aircrews completed their fuel consumption tests and Geddes decreed that they were ready to take the war to the Kurile Islands.

The Japs had used the dark winter months to strengthen their defences against the expected invasion. They transferred two divisions from Manchuria to Shimushu. More artillery and anti-aircraft batteries were installed and 20+ picket boats, some with small radar sets, patrolled the seas 2-300 miles from the eastern coastline.

It was 19th January, 1944 when three VB-139 crews assembled for their briefing. Not only on the targets; close attention was paid to the weather and wind forecasts, both over the Kuriles and over the Aleutians at the time of their return. They were briefed on a possible diversion to Kamchatka, neutral Russia. Because of that extra fuel tank their bomb load was reduced to just three 500lbs bombs, supplemented by several cases of 20 lbs fragmentation bombs which would be thrown out of hatches.

It was 19th January, 1944 when three VB-139 crews assembled for their briefing. Not only on the targets; close attention was paid to the weather and wind forecasts, both over the Kuriles and over the Aleutians at the time of their return. They were briefed on a possible diversion to Kamchatka, neutral Russia. Because of that extra fuel tank their bomb load was reduced to just three 500lbs bombs, supplemented by several cases of 20 lbs fragmentation bombs which would be thrown out of hatches.

Engine start was 30 minutes before take off to ensure that all systems were thoroughly warm at the time of the overloaded take off. At the end of the runway, the fuel truck arrived at the last minute and the tanks were topped up. Any final briefing would be given by an officer who walked from plane to plane. The 34,000 lbs bombers - 3000lbs overload - had to reach 80 knots before take off and used most of the runway to do it. Venturas had no effective heating system so the crews had borrowed electrically heated suits from the army. They warmed only the torso. Hands and feet stayed icily cold. And the system could only cope with one suit at a time so the crew had to take turns to plug into the single socket.

They flew through the turbulence of a front but the clouds cleared before they neared Kamchatka. The half hourly broadcast from the Russian’s marine radio beacon confirmed their navigation and they turned south for Shimusu. The first bomber opened the attack with a photo-flash bomb. Immediately three searchlights coned the bomber and the bursts of heavy flak and streams of tracer filled the sky. The other two bombers got the same treatment. They all had the impression that the flak was bursting behind them. Was that because the Japs didn’t realise how fast they were? Nevertheless they listened carefully to any unusual noises on the long flight home in case they had any flak damage. All went well and all three returned safely to Attu.

Geddes launched more attacks and the pattern was repeated. No aircraft was lost. In February his campaign rose to a crescendo. His ‘Empire Express’ went to Shimusu four nights in a row. On the last of these raids six PV-1s were joined by three PBYs and co-ordinated their attack with a fleet of cruisers and destroyers which bombarded the islands, damaging cargo ships as well as fortifications.

Bombers 31 and 28

Bombers 31 and 28

Then, in one respect, life got a little easier. A team of engineers came from Lockheed and fitted cross-feed lines and valves to all the tanks. On the other hand, the nights were getting shorter. If anything delayed take off time, the bombers would arrive over the Japanese islands after sunrise which would allow early detection and the possibility of being met by airborne fighters. However, it wasn’t the Japs who caused the first loss.

The runway, Massacre Bay in the foreground

The runway, Massacre Bay in the foreground

Five PV-1s were being prepared for a raid on 24th March, scheduled for a midnight take off. After all the usual fumbles and delays it was nearly 2.00 am when they lined up at the end of the runway, Bomber 25 took off first and climbed away into the clouds. Next to leave was Bomber 28. Its pilot, Lt James Moore, found it reluctant to lift off the runway. In the last few yards of the runway it began to fly. But it wasn’t climbing. Moore raised the undercarriage. The Ventura still refused to climb and slowly sank towards the waters of Massacre Bay. Its rounded belly touched the water and it skipped like a stone, falling back to crash into the sea. It burst into flames.

Five PV-1s were being prepared for a raid on 24th March, scheduled for a midnight take off. After all the usual fumbles and delays it was nearly 2.00 am when they lined up at the end of the runway, Bomber 25 took off first and climbed away into the clouds. Next to leave was Bomber 28. Its pilot, Lt James Moore, found it reluctant to lift off the runway. In the last few yards of the runway it began to fly. But it wasn’t climbing. Moore raised the undercarriage. The Ventura still refused to climb and slowly sank towards the waters of Massacre Bay. Its rounded belly touched the water and it skipped like a stone, falling back to crash into the sea. It burst into flames.

Moore was trapped in the cockpit. His boot was jammed under the rudder pedal. He unzipped the boot. Scrambling out into the icy water, he found the dinghy, which had inflated automatically. Another crewman joined him and they paddled away from the burning fuel and exploding ammunition. The other four crew died in the flames. In the aftermath, they reasoned that it was probably icing on the wing which had destroyed the lift. Another item to add to the pre take off check list.

The rescue boat was still circling the wreck when orders came from Sweat Hill - ‘Get the others rolling’. The last three bombers duly took off, passing directly over the spot where their dead comrades’ bodies were being pulled out of the water. It was now 3.00 am, fully three hours behind the originally planned take off. They would almost certainly arrive over the target in daylight.

The rescue boat was still circling the wreck when orders came from Sweat Hill - ‘Get the others rolling’. The last three bombers duly took off, passing directly over the spot where their dead comrades’ bodies were being pulled out of the water. It was now 3.00 am, fully three hours behind the originally planned take off. They would almost certainly arrive over the target in daylight.

Bomber 31 taking off on its daylight mission

Bomber 31 taking off on its daylight mission

On board Lt Whitman’s Bomber 31 was an extra crew member, a meteorologist. He would be briefing crews on future missions and was there to photograph cloud formations and get personal experience of weather fronts. He was delighted to have won his place on the toss of a coin. It was his first mission.

The four Venturas settled into their long cold flight, flying between and through cloud layers. In Bomber 25, the leading plane, the crew realised that the port engine was using excessive amount of fuel. The ‘how-goes-it’ chart told them they had insufficient fuel to complete the mission and get back home. Maintaining radio silence, they turned back.

The four Venturas settled into their long cold flight, flying between and through cloud layers. In Bomber 25, the leading plane, the crew realised that the port engine was using excessive amount of fuel. The ‘how-goes-it’ chart told them they had insufficient fuel to complete the mission and get back home. Maintaining radio silence, they turned back.

Half an hour later, the second bomber reached Kamchatka and swung south to follow the coast. Suddenly a turbulent updraft thrust them up from 9,000 to 14,000 ft. They had encountered an eruption from one of Kamchatka’s volcanoes. Soon they identified the target, first on radar then it became visible through heavy haze. Lt. Neal dived down and released his bombs three minutes after sunrise. The Japanese defences were relaxed, taken by surprise. There had been no daylight raids for months. The Ventura escaped unscathed.

Lt Norem, in the third bomber, estimated that he was about 30 minutes from Kamchatka. He was unable to hear its beacon because of static so turned on his radar. He was surprised to find he had overshot the peninsula and was over the Sea of Okhotsk to its west and heading for Vladivostok. He must have been blown there by an unforecast wind. He might have to fight against this on the long way home. Norem jettisoned his bombs and turned east. Now there was only Lt Whitman in Bomber 31 to attack the target - in daylight. His last transmission was heard. It was ‘Down. Down’.

Bomber 25 was the first to return to Attu after 6 hrs 37 mins in the air. Lt Neal, the only one to complete the five plane mission successfully, landed after 10 hrs 38 mins. Norem was last to return after 10hrs 53 mins. That afternoon six planes were launched to search the seas, hoping to find Whitman and his crew’s dinghy. Nothing was seen. Some days later Tokyo Rose’s radio broadcast from Japan announced that the crew had been captured. It was false, of course. Everyone hoped that they were safe in Russia.

Lt Norem, in the third bomber, estimated that he was about 30 minutes from Kamchatka. He was unable to hear its beacon because of static so turned on his radar. He was surprised to find he had overshot the peninsula and was over the Sea of Okhotsk to its west and heading for Vladivostok. He must have been blown there by an unforecast wind. He might have to fight against this on the long way home. Norem jettisoned his bombs and turned east. Now there was only Lt Whitman in Bomber 31 to attack the target - in daylight. His last transmission was heard. It was ‘Down. Down’.

Bomber 25 was the first to return to Attu after 6 hrs 37 mins in the air. Lt Neal, the only one to complete the five plane mission successfully, landed after 10 hrs 38 mins. Norem was last to return after 10hrs 53 mins. That afternoon six planes were launched to search the seas, hoping to find Whitman and his crew’s dinghy. Nothing was seen. Some days later Tokyo Rose’s radio broadcast from Japan announced that the crew had been captured. It was false, of course. Everyone hoped that they were safe in Russia.

The first American aircraft to arrive in eastern Russia was as far back as 18th April 1942. Captain York’s B-25 - one of the Doolittle raiders - had bombed Tokyo and landed near Vladivostok. The second was Lt Pottinger’s B-24 which crashed in Kamchatka on 11th August 1943. Since then, there had been more than a trickle of damaged, short of fuel bombers which had diverted to the safe haven of Petropavlosk. A growing number of abandoned American bombers were parked in a corner of its airfield. The reception of the crews had varied. Those who had flown over a naval base had the traditional burst of gunfire, some had been met and escorted to landing by Polikarpov I-16 Rata fighters.

Most were met after landing by the point of a rifle and a gesture to come forward, one at a time to be searched for weapons. Some who used their pseudo-Russian to announce that they were ‘Americanski’ and were rewarded with hugs and the occasional kiss. Overall they were treated as uninvited guests.

When the US learned that the Doolittle raiders were in Russia the US Ambassador opened negotiations to have them re-patriated. It would have been easy enough to have slipped them on board one of the fleet of Russian merchant ships which plied between Vlad. and California. (More than 50% of America’s aid to Russia came that way.) However, Stalin had signed a Neutrality Pact with Japan in April 1941 even though he had plans to invade Manchuria, currently occupied by Japan. The German invasion of Russia in June 1941 put these plans on hold. All his forces were dealing with the German threat. It was essential that Russia’s neutrality in the Pacific should be maintained. The B-25 crew stayed in Vladivostok - for the time being. Nevertheless, after a suitable interval they were shuffled west by various means of transport - rail, lorry, even the occasional short flight. After thirteen long months, they wound up in Meshed, in northern Iran. (That’s in the Russian occupied part of Iran. The country had been overrun by the British and Russians after the Shah had refused to expel the large number of German technicians and ‘advisers’ working in his country.)

From Meshed, it was easy for the Americans, in ‘relaxed’ internment, to contact the British Ambassador in Teheran. He arranged for them to follow a roundabout route through various countries in Asia and Africa before eventually being flown to the US. There, it was stressed that their journeyings and escape must remain a close secret.

The Americans in Petropavlosk knew nothing of this, of course. They were accommodated in a log built barracks, sparsely furnished. On arrival, they had all been interrogated, a process they enjoyed because the interrogator was a young woman, their first female contact for months, Nevertheless, they all stuck to the ‘navigation training mission’ story and the Russians soon lost interest. Their movements were restricted - there was nowhere interesting to go anyway - and they spent their days playing games, cards and chess. The Russians did find a volley ball, which extended their activities. Some took lessons, learning to speak at least basic Russian. Meals, usually fish soup and black bread served three times a day, were no more than adequate. There was no spare clothing available and no reading material in English. They were soon aware that the Russians seemed to be living in extreme poverty. The only ‘news’ they heard was from the latest crew to divert to Kamchatka. There was one highlight in their boring existence It came one day when they were taken in small groups to the harbour where a kindly captain allowed them to use the ship’s showers

When the US learned that the Doolittle raiders were in Russia the US Ambassador opened negotiations to have them re-patriated. It would have been easy enough to have slipped them on board one of the fleet of Russian merchant ships which plied between Vlad. and California. (More than 50% of America’s aid to Russia came that way.) However, Stalin had signed a Neutrality Pact with Japan in April 1941 even though he had plans to invade Manchuria, currently occupied by Japan. The German invasion of Russia in June 1941 put these plans on hold. All his forces were dealing with the German threat. It was essential that Russia’s neutrality in the Pacific should be maintained. The B-25 crew stayed in Vladivostok - for the time being. Nevertheless, after a suitable interval they were shuffled west by various means of transport - rail, lorry, even the occasional short flight. After thirteen long months, they wound up in Meshed, in northern Iran. (That’s in the Russian occupied part of Iran. The country had been overrun by the British and Russians after the Shah had refused to expel the large number of German technicians and ‘advisers’ working in his country.)

From Meshed, it was easy for the Americans, in ‘relaxed’ internment, to contact the British Ambassador in Teheran. He arranged for them to follow a roundabout route through various countries in Asia and Africa before eventually being flown to the US. There, it was stressed that their journeyings and escape must remain a close secret.

The Americans in Petropavlosk knew nothing of this, of course. They were accommodated in a log built barracks, sparsely furnished. On arrival, they had all been interrogated, a process they enjoyed because the interrogator was a young woman, their first female contact for months, Nevertheless, they all stuck to the ‘navigation training mission’ story and the Russians soon lost interest. Their movements were restricted - there was nowhere interesting to go anyway - and they spent their days playing games, cards and chess. The Russians did find a volley ball, which extended their activities. Some took lessons, learning to speak at least basic Russian. Meals, usually fish soup and black bread served three times a day, were no more than adequate. There was no spare clothing available and no reading material in English. They were soon aware that the Russians seemed to be living in extreme poverty. The only ‘news’ they heard was from the latest crew to divert to Kamchatka. There was one highlight in their boring existence It came one day when they were taken in small groups to the harbour where a kindly captain allowed them to use the ship’s showers

The swelling numbers of internees on Kamchatka at last had something to look forward to. The earliest arrivals, the Air Force fliers, were moved out. Sixty one of them boarded a train, a flying boat or a Lisunov Li-2 (that’s the Russian built C-47). They made their wandering way across Siberia to Tashkent. Finally, a truck convoy took them into Iran where they were simply handed over to the US forces there.

Other groups followed, all taking different routes, sometimes spending weeks in a camp or barracks.

Other groups followed, all taking different routes, sometimes spending weeks in a camp or barracks.

The last group of 90+ Americans were nearing Iran and found themselves ‘arrested’ and held in confinement, under guard. A story had appeared in the American press about the ‘escape‘ of the Doolittle crew. Waiting for the reaction of the Japanese the Russian attitude changed. They now seemed to regard the Americans as prisoners and treated them accordingly. Weeks passed. The morale and health of the ‘prisoners’ deteriorated. Thirty of them decided to escape. After all, it was only 18 miles to the Iranian border. But that 18 miles was largely snow covered mountains. Most were quickly recaptured. Some returned voluntarily. A curious Christmas, with muted celebration passed. Finally, on 29th January, 1945 they climbed into unheated railway trucks and travelled 150 miles west, a three day journey, to the border crossing. They transferred into, also unheated, trucks for another three night and day bumpy ride towards Teheran. There they were housed in an empty hospital, given unlimited American food, new uniforms and slept in clean bed sheets.

Back in the Aleutians, the attacking missions went on, increasing in intensity. A new commander of the Air Force units brought in squadrons of B-24 Liberators and B-25 Mitchells. The Mitchells were modified, like the Navy’s Venturas, to have extra fuel tanks fitted. Commander Geddes and his long suffering VB-139 went back to the mainland States and were replaced by VB-136 whose Venturas gave up bombs and attacked with eight 5-inch rockets. Six months later the refreshed VB-139 came back with PV-2 Harpoons. With a new larger wing they could carry 4000 lbs of bombs and more fuel. The bomb aimer’s position in the nose was replaced by an aggressive package of five 0.50in guns which, with the rockets, gave the PV-2 considerable strafing power. Two more fifties faced aft in the hatch in the tail.

Back in the Aleutians, the attacking missions went on, increasing in intensity. A new commander of the Air Force units brought in squadrons of B-24 Liberators and B-25 Mitchells. The Mitchells were modified, like the Navy’s Venturas, to have extra fuel tanks fitted. Commander Geddes and his long suffering VB-139 went back to the mainland States and were replaced by VB-136 whose Venturas gave up bombs and attacked with eight 5-inch rockets. Six months later the refreshed VB-139 came back with PV-2 Harpoons. With a new larger wing they could carry 4000 lbs of bombs and more fuel. The bomb aimer’s position in the nose was replaced by an aggressive package of five 0.50in guns which, with the rockets, gave the PV-2 considerable strafing power. Two more fifties faced aft in the hatch in the tail.

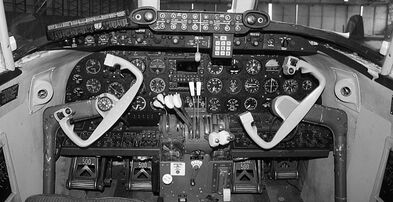

PV-2 Harpoon

PV-2 Harpoon

As the days lengthened in the spring of 1945 daylight raids were resumed, always at very low level. Ships of the US Navy used banks of dense fog to get close enough the Kuriles to bombard port installations and airfields. And all this time throughout the hard fought war against the Japanese and the climate, the losses continued. Planes were shot down, staggered to Russia or just disappeared

The Americans’ plans for the invasion of the Kuriles were dusted off but it never seemed the right time to activate them. Then, suddenly, it was all over. The atom bombs were dropped on the 6th and 9th August. On the 14th Emperor Hirohito announced to the world that Japan was surrendering.

The war wasn’t over in the Kuriles. At the Yalta Conference in February, 1945 Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin had set out their ideas for the shape of the post-war world. It included an invasion which Stalin intended to implement as soon as thousands of his soldiers had been transferred from the battlefields of Europe to Siberia. Until then determinedly neutral in the Pacific area, Stalin tore up the 1941 treaty with Japan and his armies stormed into Manchuria. It was on 8th August, between bombs as it were.

The long-anticipated invasion of the Kuriles was now going to happen, not by the Americans, but by Soviet soldiers. The landing craft that drove onto the fog-ridden beaches of Shimushu on the morning of 18th August were met by a party of Japanese waving a white flag. It was ignored. The Russians fired their guns at anything and everything. The Japanese commander called up his tank regiment. As the fog lifted aircraft from both sides joined in. By the time ‘orders from above’ calmed down the combatants every tank had been destroyed and the Russians had suffered more than 3,000 casualties. In contrast, Paramushiro was occupied a few days later without a fight.

The Russians took control of all the fifty six Kurile islands, very few having any occupants, many just isolated rocks breaking the surface. Japan claimed that they should retain sovereignty over the four southern islands - that claim is in abeyance. Russia also occupied Manchuria and North Korea, one to be absorbed by the Soviet Union, the other to have its own Communist ruler. By the time this brief war was over, more than 600,000 Japanese were POWs of the Soviets. Some civilians were released, most were sent to gulags, forced labour camps. Those who were still alive after an indeterminate number of years ‘service’ were released.

For the thousands of Americans in the Aleutians VJ Day was a day of unmitigated celebration, a day of relief that their own particular war had come to an end, a war that had achieved so little and had cost so much, a war in which more men were killed by the climate than by the enemy. Their campaign became referred to as ‘The Forgotten War’. Historians date it June 1942 - August 1943. In fact, that’s just the soldiers’ war, during which the Japanese were cleared off Attu and Kiska was reoccupied. The airmen’s bombing campaign went on from August 1943 until the very last day of World War II. One cynic dismissed it as no more than ‘pecking at the walls of a fortress’. He asserted that the airmen’s war had not been forgotten - it had never even been noticed. And the cost - 38 B-24s, 34 B-25s, 42 PVs-1 and 2 and many of their crews.

The war wasn’t over in the Kuriles. At the Yalta Conference in February, 1945 Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin had set out their ideas for the shape of the post-war world. It included an invasion which Stalin intended to implement as soon as thousands of his soldiers had been transferred from the battlefields of Europe to Siberia. Until then determinedly neutral in the Pacific area, Stalin tore up the 1941 treaty with Japan and his armies stormed into Manchuria. It was on 8th August, between bombs as it were.

The long-anticipated invasion of the Kuriles was now going to happen, not by the Americans, but by Soviet soldiers. The landing craft that drove onto the fog-ridden beaches of Shimushu on the morning of 18th August were met by a party of Japanese waving a white flag. It was ignored. The Russians fired their guns at anything and everything. The Japanese commander called up his tank regiment. As the fog lifted aircraft from both sides joined in. By the time ‘orders from above’ calmed down the combatants every tank had been destroyed and the Russians had suffered more than 3,000 casualties. In contrast, Paramushiro was occupied a few days later without a fight.

The Russians took control of all the fifty six Kurile islands, very few having any occupants, many just isolated rocks breaking the surface. Japan claimed that they should retain sovereignty over the four southern islands - that claim is in abeyance. Russia also occupied Manchuria and North Korea, one to be absorbed by the Soviet Union, the other to have its own Communist ruler. By the time this brief war was over, more than 600,000 Japanese were POWs of the Soviets. Some civilians were released, most were sent to gulags, forced labour camps. Those who were still alive after an indeterminate number of years ‘service’ were released.

For the thousands of Americans in the Aleutians VJ Day was a day of unmitigated celebration, a day of relief that their own particular war had come to an end, a war that had achieved so little and had cost so much, a war in which more men were killed by the climate than by the enemy. Their campaign became referred to as ‘The Forgotten War’. Historians date it June 1942 - August 1943. In fact, that’s just the soldiers’ war, during which the Japanese were cleared off Attu and Kiska was reoccupied. The airmen’s bombing campaign went on from August 1943 until the very last day of World War II. One cynic dismissed it as no more than ‘pecking at the walls of a fortress’. He asserted that the airmen’s war had not been forgotten - it had never even been noticed. And the cost - 38 B-24s, 34 B-25s, 42 PVs-1 and 2 and many of their crews.

The weary troops packed their equipment, tidied up the debris of war and sailed to the sunnier climes of the lower 48. The unserviceable aircraft were shipped, and many serviceable ones flown to a huge dump at Anchorage to be scrapped.

The native Aleutians, strictly Unanagan people spent the war in a camp in mainland Alaska. They were returned to the islands but were not allowed to settle on Attu. That island, the closest to the Soviet empire, is controlled by the military. The US Coastguard occasionally use the large concrete runway which was built there. Most people who call the Aleutians home, live on the largest island, Unalaska, at the Eastern end of the chain.

The native Aleutians, strictly Unanagan people spent the war in a camp in mainland Alaska. They were returned to the islands but were not allowed to settle on Attu. That island, the closest to the Soviet empire, is controlled by the military. The US Coastguard occasionally use the large concrete runway which was built there. Most people who call the Aleutians home, live on the largest island, Unalaska, at the Eastern end of the chain.

Post Script.

In 1962 a survey team from a Russian Geology Technical School was in Kamchatka and came across the wreck of a crashed bomber. It was obviously a PV-1 Ventura. Was it the long missing Bomber 31? Seventeen years of harsh weathering had removed any markings which would have confirmed its identity. Other scattered wreckage was found nearby from another bomber which had not force landed, this one had flown into the ground. Human remains were found in or close to four flying jackets and helmets. The site had clearly been visited by wild animals and the team had the grisly job of collecting things like finger bones as well as other personal items which might help identify the bodies.

In 1962 a survey team from a Russian Geology Technical School was in Kamchatka and came across the wreck of a crashed bomber. It was obviously a PV-1 Ventura. Was it the long missing Bomber 31? Seventeen years of harsh weathering had removed any markings which would have confirmed its identity. Other scattered wreckage was found nearby from another bomber which had not force landed, this one had flown into the ground. Human remains were found in or close to four flying jackets and helmets. The site had clearly been visited by wild animals and the team had the grisly job of collecting things like finger bones as well as other personal items which might help identify the bodies.

All these were handed over to someone in authority, the local KGB (Security) man. He decided to take no action, to tell no one. It was only after another visit some years later by the geology team and much prompting that the items were sent off, eventually arriving in the States. They proved to be from the crew of Bomber 31 which had crashed after suffering from battle damage.

So this is not Bomber 31. But it is the last survivor of the hardly noticed war fought in the far fringes of the Pacific by a group of courageous airmen, It is their anonymous, silent, isolated and unvisited memorial.

So this is not Bomber 31. But it is the last survivor of the hardly noticed war fought in the far fringes of the Pacific by a group of courageous airmen, It is their anonymous, silent, isolated and unvisited memorial.