The One-eyed Record Breaker - Wiley Post - 1898-1935. (June 2018)

Wiley Post - aged 19

Wiley Post - aged 19

Wiley Post was born in Texas in 1898, the youngest son of a farmer. But he had no interest in farming, or in school. It wasn’t until he was 14 and saw ‘one of them new-fangled airplanes’ that he found an aim in life – he wanted to fly. He learned what he could about things mechanical and saved up enough money to take a seven-month course at the Sweeney Auto School.

When the US entered the First World War in 1917, he enrolled in the Students Army Training Corps which he hoped might lead to flying training. He did learn about radio, then the war ended and the Corps was disbanded. Having paid a barnstormer for his first flight he realised that he would need lots of money to make his own way in aviation. So he took a job in the developing oilfields of Oklahoma.

It was a rough life. In 1921, Wiley fell foul of the law and was convicted of armed robbery of a car. The harsh sentence of 10 years in the Oklahoma State Reformatory was eased by the granting of parole after 13 months. In 1924 he heard of a ‘flying circus’ which was due to visit a nearby town. Wiley went there and met Burrell Tibbs and his ‘Texas Topnotch Fliers’. He found out that their parachute jumper wouldn’t be performing because of an injury. Immediately he offered to do the jump and was so persistent that Tibbs agreed.

His performance impressed Tibbs and Wiley was able to talk himself into a job with the Circus. Travelling between venues he was able to get snatches of instruction in flying the Jennies. Soon he realised that he could make more money jumping for himself, rather than as part of the team. He could charge $200 for a jump, hiring a pilot and plane for just $25.

In two years, he made 99 jumps and also picked up more free instruction from a friendly Jenny owner. In 1926 this man actually sent Wiley off on his first solo flight. It was far too early and Wiley lost control two or three times. He realised he needed a course of proper instruction and, of course, the money to pay for it. He went back to the Oklahoma oilfields to get a regular income.

It was a fateful move. One day he was supervising the drilling of a new well when a metal fragment struck his left eye. The eye became infected and it threatened to spread to the other eye. The doctors recommended that his left eye should be removed. It seemed as though, without depth perception, his aviation dream had been shattered. Nevertheless, he practised estimating a distance to, say, a tree and pacing it out to check.

When a workman’s compensation scheme gave him a payment of almost $1700, he used $200 to by a damaged Canuck (a Canadian built Jenny) and spent $340 to have it repaired. At this time in Oklahoma there was no such thing as a pilot’s licence so Wiley could legally fly – and charge – passengers. He began barnstorming and just about made a living for himself and his new wife. Then his Canuck was damaged in a ground accident in Mexico. He got it back to the repair shop but couldn’t afford to have it fixed.

In two years, he made 99 jumps and also picked up more free instruction from a friendly Jenny owner. In 1926 this man actually sent Wiley off on his first solo flight. It was far too early and Wiley lost control two or three times. He realised he needed a course of proper instruction and, of course, the money to pay for it. He went back to the Oklahoma oilfields to get a regular income.

It was a fateful move. One day he was supervising the drilling of a new well when a metal fragment struck his left eye. The eye became infected and it threatened to spread to the other eye. The doctors recommended that his left eye should be removed. It seemed as though, without depth perception, his aviation dream had been shattered. Nevertheless, he practised estimating a distance to, say, a tree and pacing it out to check.

When a workman’s compensation scheme gave him a payment of almost $1700, he used $200 to by a damaged Canuck (a Canadian built Jenny) and spent $340 to have it repaired. At this time in Oklahoma there was no such thing as a pilot’s licence so Wiley could legally fly – and charge – passengers. He began barnstorming and just about made a living for himself and his new wife. Then his Canuck was damaged in a ground accident in Mexico. He got it back to the repair shop but couldn’t afford to have it fixed.

He had to sell the Canuck. J Bart Scott gave him $350, had the plane repaired and employed Wiley as his pilot, flying passengers and instructing pupils. Wiley was earning just $3 per flying hour and, when customers were few in the winter of 1927, life was hard. He began to look around for another job.

He was asked to fly to see two oilmen who were considering using an aeroplane in their business (they had missed a deal by arriving later than a sharper competitor).

Wiley impressed them sufficiently to get the job as their pilot at $200 a month, flying them around in a TravelAir 3-seat biplane. But in Wiley’s life of ups and down there was always a cloud on the horizon.

He was asked to fly to see two oilmen who were considering using an aeroplane in their business (they had missed a deal by arriving later than a sharper competitor).

Wiley impressed them sufficiently to get the job as their pilot at $200 a month, flying them around in a TravelAir 3-seat biplane. But in Wiley’s life of ups and down there was always a cloud on the horizon.

The Aeronautics Branch of the US Department of Commerce had devised a licensing system for airmen and its use was spreading. Wiley could not do his job properly whilst avoiding airfields where there were government inspectors. He needed a ‘Transport Pilot’s’ licence. This specified competence and medical standards. How could he qualify with one eye? Fortunately, in the case of ‘trained and experienced aviators’ it was possible for waivers to be granted. Wiley easily passed the written test and was allowed a ‘probationary period’ to reach 700 hours as pilot-in-charge. This was sufficient for his monocular eyesight to be accepted and he was granted a full air transport licence in September 1928. He had achieved his boyhood goal at the age of 30.

The oilmen soon tired of open cockpit flying and looked for a better plane. Alan Loughhead was touring Texas and Oklahoma demonstrating his new Vega with a comfortable cabin and a fast cruise. After one flight in it, the oilmen placed an order. Wiley flew the TravelAir to California and came back in a Vega, the 24th off the production line. (This model did not have the cowl over the engine’s cylinders, nor the streamlined pants over the wheels. They were yet to be produced). Florence Hall, the owner, named it after his daughter, Winnie Mae. They were not to enjoy it for long. The following year was 1929 when the stock market crashed and the Vega was sold back to the factory. Wiley was fortunate to be taken on by Lockheed as a test and delivery pilot.

The oilmen soon tired of open cockpit flying and looked for a better plane. Alan Loughhead was touring Texas and Oklahoma demonstrating his new Vega with a comfortable cabin and a fast cruise. After one flight in it, the oilmen placed an order. Wiley flew the TravelAir to California and came back in a Vega, the 24th off the production line. (This model did not have the cowl over the engine’s cylinders, nor the streamlined pants over the wheels. They were yet to be produced). Florence Hall, the owner, named it after his daughter, Winnie Mae. They were not to enjoy it for long. The following year was 1929 when the stock market crashed and the Vega was sold back to the factory. Wiley was fortunate to be taken on by Lockheed as a test and delivery pilot.

Hall’s business picked up remarkably quickly and in June 1930 he was able to place another order for a Vega which again carried the name Winnie Mae on its white, purple-trimmed fuselage.

Hall was an aviation enthusiast and had in the past sponsored several events. Wiley had no trouble in persuading him to enter the Vega in the forthcoming aerial derby, a race from Los Angeles to Chicago.

Wiley arranged for a 10:1 supercharger to be fitted replacing the engine’s standard 7:1 unit. This needed an enlarged intake which sat in front of the pilot’s windscreen, worsening the already seriously restricted view from the cockpit.

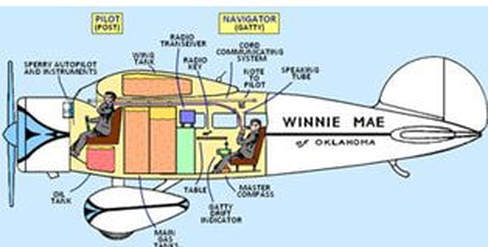

By replacing the seats with an extra fuel tank Wiley knew he would have the range to reach New York after over-flying Chicago, a secondary aim. In planning the route, he sought the advice of Harold Gatty, an Australian living in California, who was acknowledged to be an expert in navigation.

By replacing the seats with an extra fuel tank Wiley knew he would have the range to reach New York after over-flying Chicago, a secondary aim. In planning the route, he sought the advice of Harold Gatty, an Australian living in California, who was acknowledged to be an expert in navigation.

In the event, the carefully prepared plans failed – partly. It wasn’t long after take-off that Wiley realised that his compass had failed and he was seriously off course. He had to resort to what was known as pilotage – map reading. He reckoned it cost him 40 minutes in the race – and he had to abandon his transcontinental speed record attempt. Still, despite the off-course excursion he logged the shortest time to Chicago and won the race. The $7500 was a good consolation prize.

The publicity surrounding the aerial derby rocketed Wiley from an unknown jobbing pilot with a questionable background and a missing eye to a position of fame as an expert, race winning folk hero. Winnie Mae’s owner and pilot talked about doing something more – something unusual.

The possibilities and plans condensed into a round-the-world flight. Three Douglas World Cruisers had taken 175 days to get round in 1924 and the Graf Zeppelin took 21 days. That was a record that Winnie Mae could beat.

The publicity surrounding the aerial derby rocketed Wiley from an unknown jobbing pilot with a questionable background and a missing eye to a position of fame as an expert, race winning folk hero. Winnie Mae’s owner and pilot talked about doing something more – something unusual.

The possibilities and plans condensed into a round-the-world flight. Three Douglas World Cruisers had taken 175 days to get round in 1924 and the Graf Zeppelin took 21 days. That was a record that Winnie Mae could beat.

Once again, he involved Harold Gatty. Trained as a ship’s navigator Gatty moved to the States in 1927 and now ran a navigation school for aviators. Wiley concentrated on preparing the Vega.

He had the Pratt and Whitney Wasp completely overhauled in the TWA workshops, removing the electric starter to save weight. He got the Lockheed factory to reduce the angle of incidence of the wing. This was to align the fuselage with the airflow at his high cruising speed and so minimize drag. It would mean faster landing speeds – about 80 mph - so he had the length of the tail skid reduced allowing him to raise the nose a little higher at touchdown.

He had the Pratt and Whitney Wasp completely overhauled in the TWA workshops, removing the electric starter to save weight. He got the Lockheed factory to reduce the angle of incidence of the wing. This was to align the fuselage with the airflow at his high cruising speed and so minimize drag. It would mean faster landing speeds – about 80 mph - so he had the length of the tail skid reduced allowing him to raise the nose a little higher at touchdown.

Harold Gatty would be sitting in the cabin with the extra fuel tank and his seat was not fixed so that he could move fore and aft to compensate for the changing CG position as the fuel was used. They installed a speaking tube which proved to be almost useless because it also carried the blare of the engine. Instead they had to resort to a string passing round two pulleys to pass notes to each other. A Morse key operated radio was fitted. It was intended only to call for rescue if the Vega had to force land at some inaccessible spot. Wiley resented its dead weight.

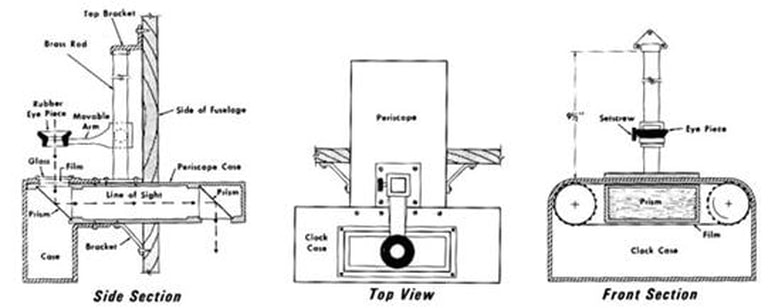

The instrument panel was re-arranged to group the blind-flying instruments together and a duplicate set of some instruments was fitted in the cabin for Gatty. An extra hatch was cut in the roof with a windshield to allow him to make sightings. To aid his navigation he designed an ingenious instrument to check drift and groundspeed.

Gatty showing his instrument to the Army.

Gatty showing his instrument to the Army.

It was a periscope fitted in a hole at the side of the fuselage. Through the eyepiece Gatty could see the ground below. A loop of clear film with graduated markings was fitted so that they superimposed on the view of the ground. The film rollers were driven by clockwork and the markings moved across the view at a steady speed. Gatty moved the eyepiece to zoom in on the ground view until the speed of movement of the ground and the markings were the same. His scale and the height of the aeroplane then told him the precise ground speed. Another rotating graticule measured the drift. Tests proved that It worked equally well over land, water and ice.

Wiley was well aware that a serious factor in the flight would be staying awake. He was urged to get himself fit with an exercise programme. ‘That’s useless’, he said. ‘All I’m going to do is sit’. He had a comfortable seat made with adjustable arm rests and turned his attention to something that no-one had ever considered, or needed to – what we now call jet lag. Passing through many time zones his sleep would be disrupted as well as limited. In the months before the flight he slept at different hours every day so that he had no regular pattern. He also practised sitting relaxed for long periods trying to keep his mind blank without falling asleep.

There was a political problem to overcome. They contacted all the countries they would be flying through or over but they couldn’t do this with Russia. In 1931, the USA did not recognise the Soviet Union and their planned route went right through Russia from west to east with several refuelling stops on the way. Florence Hall was able to help. Through his business contacts he found some-one who regularly dealt with the Russian Amtorg Trading Corporation. Via personal contacts and calling in favours they eventually got the required permission for the flight.

When all was finally ready Post and Gatty flew Winnie Mae to New York on 23rd May. They planned to take off from Roosevelt Field in Long Island, which had been the departure point for Lindbergh and the other Orteig Prize competitors four years before. There they waited for the prognostications of Dr James Kimball of the US Weather Bureau. Forecasting was an inexact science in 1931 and Kimball was looking at a wide area from the USA, across the wide Atlantic and into Europe.

There was a political problem to overcome. They contacted all the countries they would be flying through or over but they couldn’t do this with Russia. In 1931, the USA did not recognise the Soviet Union and their planned route went right through Russia from west to east with several refuelling stops on the way. Florence Hall was able to help. Through his business contacts he found some-one who regularly dealt with the Russian Amtorg Trading Corporation. Via personal contacts and calling in favours they eventually got the required permission for the flight.

When all was finally ready Post and Gatty flew Winnie Mae to New York on 23rd May. They planned to take off from Roosevelt Field in Long Island, which had been the departure point for Lindbergh and the other Orteig Prize competitors four years before. There they waited for the prognostications of Dr James Kimball of the US Weather Bureau. Forecasting was an inexact science in 1931 and Kimball was looking at a wide area from the USA, across the wide Atlantic and into Europe.

There were many false starts and it took a whole month before Dr Kimball produced a favourable forecast shortly after midnight on 23rd June. Wiley was ready to go but the grass airfield was wet with rain and the well fuelled Winnie Mae was heavy. They waited a few hours for the surface to dry and take off was at 4.55 am, still in darkness.

Just under seven hours later, they landed at Harbour Grace in Newfoundland, from where Alcock and Brown had set off in their Vimy in 1919. In the picture the small fairing over Gatty’s periscope drift meter is visible below the cabin windows.

Just under seven hours later, they landed at Harbour Grace in Newfoundland, from where Alcock and Brown had set off in their Vimy in 1919. In the picture the small fairing over Gatty’s periscope drift meter is visible below the cabin windows.

Their next leg was 1,900 miles across the Atlantic with long periods of blind flying for Wiley until landing at RAF Sealand in Cheshire. Harold found that he didn’t like Wiley’s technique of not changing tanks until the engine spluttered and coughed. Wiley wanted to be sure that the tank was really empty.

They flew on to Hanover. After take off, both men were suffering from lack of sleep and neither could remember having refuelled there. So they flew back and added a few gallons, sufficient to reach Berlin where they were greeted by large crowds and playing bands. They seized the chance of sleeping most of the night and left early next morning for Moscow. Low clouds and heavy rain dogged their navigation on the 994 mile flight. Gatty deliberately aimed for a point north of Moscow so that, when they sighted the Volga they knew they had to turn right to find their destination.

Although there were few people to greet them, they were taken to a nine-course banquet, with many representatives from the Western press. They sat through numerous toasts, drinking only water and eating little. After fitting in two hours sleep, they prepared to leave. The Russians had refuelled Winnie Mae but used Imperial instead of US gallons. The plane was overloaded by nearly 400 lbs. The Russians were bemused when Post and Gatty siphoned off the excess fuel. The engine was started by pulling a rope attached to a boot which was fitted over a prop blade tip.

At Novosibirsk there was another banquet, three hours sleep disturbed by bed bugs and on to Irkutsk, then Blagoveskchensk to land in the dark. The Russians had laid out a string of oil fires to mark the landing run on the flooded airfield. Gatty moved his seat back to help slow the landing. Winnie splashed through two inches of water before ploughing a furrow and sinking axle deep into the mud. The welcoming committee included two Danish telegraph operators who spoke English. They arrived on an ancient tractor, not powerful enough to pull Winnie to a drier spot. After much multi-lingual chat they all went off, taking Harold, to get a bigger tractor and some food. Wiley, irritated beyond words, stayed in the aeroplane and went to sleep.

Harold was taken to the house of one of the Danes. He enjoyed a hot meal, a bath and two hours sleep. Then they went back to wake up Wiley. The tractor hadn’t arrived. Much chat later, they brought a couple of horses. The flood had drained away but the mud still held Winnie fast. It was another five hours – another valuable sleeping bonus – before the ground was dry enough for the horses and a bit of digging to release Winnie and towed her to a drier part of the field for refuelling. They had been on the ground for over 12 hours, losing time but gaining sleep.

At the next stop, Khabarovsk, Wiley and Harold reviewed the situation. They were 5½ days into the journey – behind their planned time – and ahead of them lay the most difficult stage. The maps they’d be given by the Russians were sketchy with mountains vaguely indicated. Then there were wide stretches of water before reaching the stop in Solomon, Alaska. Wiley got a Japanese weather report hinting they would be a gap in the string of depressions passing across the Bering Straits. He decided to cancel the last Russian stop at Petropavolovsk and fly directly to Solomon. They caught a few hours sleep and at 6.56 pm local time, lifted the fully fuelled Winnie into the air.

Conditions were rough. Sometimes they flew low to avoid headwinds, sometimes climbing to avoid mountains which were higher than the maps said and also climbing higher into clear air for Harold to take essential sun shots. Approaching Alaska, Wiley let down beneath the cloud layers to identify his position. They were on course for Solomon and, after 2,500 miles and 17 hours in the air, they landed on the beach airstrip.

Taxiing back along the beach the wheels began to sink in a patch of soft sand. Wiley gave a quick burst of throttle but the wheels stuck and the tail rose into the air. Wiley switched off quickly and the tail sank back. However the propeller had struck the sand and both tips were bent forwards. They assembled their tools, a wrench, a hammer with a broken shaft and a convenient stone. Banging and bending got the blades somewhere near normal and they prepared to start the still warm engine. Harold turned the prop for a brief prime and called ‘All clear’. Wiley switched on and ‘whirled the booster’. One of the cylinders kicked and the blade flew back and struck Harold on the shoulder. Luckily, he had been hit by the flat side of the blade which gave him only a nasty bruise. Had the prop turned the other way he would have almost certainly been killed.

They flew on to Hanover. After take off, both men were suffering from lack of sleep and neither could remember having refuelled there. So they flew back and added a few gallons, sufficient to reach Berlin where they were greeted by large crowds and playing bands. They seized the chance of sleeping most of the night and left early next morning for Moscow. Low clouds and heavy rain dogged their navigation on the 994 mile flight. Gatty deliberately aimed for a point north of Moscow so that, when they sighted the Volga they knew they had to turn right to find their destination.

Although there were few people to greet them, they were taken to a nine-course banquet, with many representatives from the Western press. They sat through numerous toasts, drinking only water and eating little. After fitting in two hours sleep, they prepared to leave. The Russians had refuelled Winnie Mae but used Imperial instead of US gallons. The plane was overloaded by nearly 400 lbs. The Russians were bemused when Post and Gatty siphoned off the excess fuel. The engine was started by pulling a rope attached to a boot which was fitted over a prop blade tip.

At Novosibirsk there was another banquet, three hours sleep disturbed by bed bugs and on to Irkutsk, then Blagoveskchensk to land in the dark. The Russians had laid out a string of oil fires to mark the landing run on the flooded airfield. Gatty moved his seat back to help slow the landing. Winnie splashed through two inches of water before ploughing a furrow and sinking axle deep into the mud. The welcoming committee included two Danish telegraph operators who spoke English. They arrived on an ancient tractor, not powerful enough to pull Winnie to a drier spot. After much multi-lingual chat they all went off, taking Harold, to get a bigger tractor and some food. Wiley, irritated beyond words, stayed in the aeroplane and went to sleep.

Harold was taken to the house of one of the Danes. He enjoyed a hot meal, a bath and two hours sleep. Then they went back to wake up Wiley. The tractor hadn’t arrived. Much chat later, they brought a couple of horses. The flood had drained away but the mud still held Winnie fast. It was another five hours – another valuable sleeping bonus – before the ground was dry enough for the horses and a bit of digging to release Winnie and towed her to a drier part of the field for refuelling. They had been on the ground for over 12 hours, losing time but gaining sleep.

At the next stop, Khabarovsk, Wiley and Harold reviewed the situation. They were 5½ days into the journey – behind their planned time – and ahead of them lay the most difficult stage. The maps they’d be given by the Russians were sketchy with mountains vaguely indicated. Then there were wide stretches of water before reaching the stop in Solomon, Alaska. Wiley got a Japanese weather report hinting they would be a gap in the string of depressions passing across the Bering Straits. He decided to cancel the last Russian stop at Petropavolovsk and fly directly to Solomon. They caught a few hours sleep and at 6.56 pm local time, lifted the fully fuelled Winnie into the air.

Conditions were rough. Sometimes they flew low to avoid headwinds, sometimes climbing to avoid mountains which were higher than the maps said and also climbing higher into clear air for Harold to take essential sun shots. Approaching Alaska, Wiley let down beneath the cloud layers to identify his position. They were on course for Solomon and, after 2,500 miles and 17 hours in the air, they landed on the beach airstrip.

Taxiing back along the beach the wheels began to sink in a patch of soft sand. Wiley gave a quick burst of throttle but the wheels stuck and the tail rose into the air. Wiley switched off quickly and the tail sank back. However the propeller had struck the sand and both tips were bent forwards. They assembled their tools, a wrench, a hammer with a broken shaft and a convenient stone. Banging and bending got the blades somewhere near normal and they prepared to start the still warm engine. Harold turned the prop for a brief prime and called ‘All clear’. Wiley switched on and ‘whirled the booster’. One of the cylinders kicked and the blade flew back and struck Harold on the shoulder. Luckily, he had been hit by the flat side of the blade which gave him only a nasty bruise. Had the prop turned the other way he would have almost certainly been killed.

They took on enough fuel to reach Fairbanks where Alaska Airways fitted a spare prop. Confidently telling reporters they would be in New York in two days they took off in the light of the ‘midnight sun’ for Edmonton in Canada. It was a difficult leg. Both men were exhausted and they struggled through bad weather over the Rockies though it cleared in time for them to pick up the railway tracks. They followed the ‘iron beam’ to Edmonton and landed on yet another rain-soaked soggy grass field.

Wiley was concerned that he wouldn’t be able to take off from the field. A Canadian airline pilot suggested that he should use Portage Avenue in town. The city fathers agreed and while Wiley and Harold slept workman removed wires and posts from the side of the paved road. They also washed the mud-spattered Winnie Mae to make her presentable for the arrival in New York.

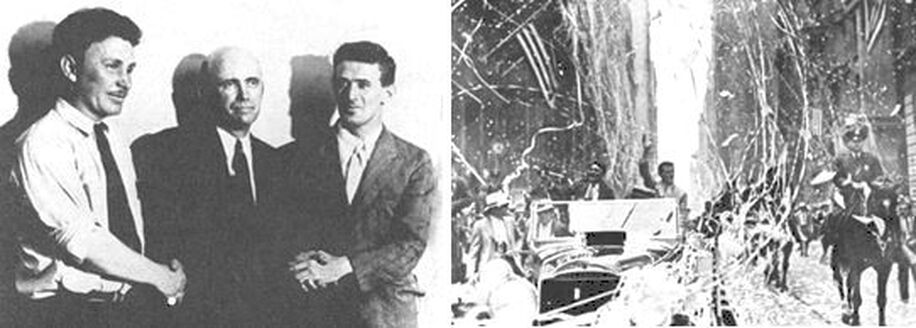

Next morning, they sped down the paved road and lifted off for Cleveland, the final refuelling stop. The large crowd that greeted them there had only 30 minutes to cheer them. As soon as enough fuel had been taken on they were off on the last leg. Other planes joined Winnie Mae for the final moments of the flight over New York City and Wiley brought the now famous Vega in to land before 10,000 people gathered on the airfield. The 15,474 mile flight had taken 8 days, 15 hours and 51 minutes although only 107 hours and 2 minutes of that was flying time.

Next morning, they sped down the paved road and lifted off for Cleveland, the final refuelling stop. The large crowd that greeted them there had only 30 minutes to cheer them. As soon as enough fuel had been taken on they were off on the last leg. Other planes joined Winnie Mae for the final moments of the flight over New York City and Wiley brought the now famous Vega in to land before 10,000 people gathered on the airfield. The 15,474 mile flight had taken 8 days, 15 hours and 51 minutes although only 107 hours and 2 minutes of that was flying time.

Overwhelmed by their reception – photographs, press, radio and filmed interviews, lunches and dinners it took ten days for Wiley to catch up on his sleep and escape with his wife to visit family and friends. Then they were plunged into a round of flying visits to Oklahoma, naturally, a tour of a-city-a-day visits and special visits to thank contributors to the flight like the Pratt and Whitney factory whose Wasp had performed faultlessly.

In all this, the major contributor, Florence Hall, was deprived of the use of his aeroplane and the services of his pilot. They agreed that he would sell the Vega to Wiley and his daughter was happy that the aeroplane could continue to carry her name. Before the flight some PR experts had predicted that Wiley would earn thousands of dollars in appearance fees after a successful flight. It was not to be. The country was still deeply in recession. Wiley ruefully calculated that his net earnings were not much more than $500. On the other hand, he hadn’t done it for the money but for the challenge.

The two record breakers wrote a book, rather hastily, aided by a professional writer and they embarked on a lecture tour. After five months, Harold Gatty went back to his business.

In all this, the major contributor, Florence Hall, was deprived of the use of his aeroplane and the services of his pilot. They agreed that he would sell the Vega to Wiley and his daughter was happy that the aeroplane could continue to carry her name. Before the flight some PR experts had predicted that Wiley would earn thousands of dollars in appearance fees after a successful flight. It was not to be. The country was still deeply in recession. Wiley ruefully calculated that his net earnings were not much more than $500. On the other hand, he hadn’t done it for the money but for the challenge.

The two record breakers wrote a book, rather hastily, aided by a professional writer and they embarked on a lecture tour. After five months, Harold Gatty went back to his business.

Wiley contemplated future flights, possibly non-stop from New York to Berlin or maybe from Tokyo to Seattle. Winnie Mae – now his Winnie Mae – was fully serviced and he planned fitting new instruments and other improvements. This was noted by the aviation community and aroused some speculation but Wiley said nothing. In truth, he wasn’t sure himself what he wanted to do. He was looking for something new to do which he hoped would further the cause of aviation.

There was an attempt to beat the 1931 Post and Gatty record. Bennett Griffin and Jimmy Mattern bought Post’s long range tanks and fitted them to their own Vega. They rigged another set of controls and instruments in the cabin so that the pilot could catch some sleep – although the only view for the rear pilot was through the side windows. In July 1932 they flew a similar route and were making good time until over Russia when the roof hatch blew off and damaged the fin. In the resulting crash, the pilots were unhurt but the Vega was wrecked.

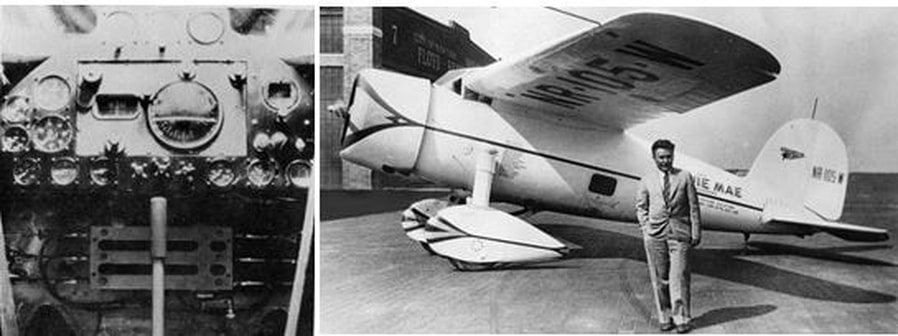

In 1933, Wiley tested the latest model of the Sperry autopilot – he called it ‘Mechanical Mike’- and also installed a gyro compass. He had the engine rebuilt with higher-compression pistons and a variable-pitch propeller fitted. Fuel tanks were installed in the cabin so that he could pump fuel between them to control the CG position. An aerial appeared on the fin. It was for a new type of radio which the US Army installed for Wiley (some details of its operation were still on the secret list). The radio was an Automatic Direction Finder that could indicate the direction of a radio beacon. A few navigation beacons were being set up, only in the USA. Elsewhere the ADF would work equally well with commercial radio transmitters.

There was an attempt to beat the 1931 Post and Gatty record. Bennett Griffin and Jimmy Mattern bought Post’s long range tanks and fitted them to their own Vega. They rigged another set of controls and instruments in the cabin so that the pilot could catch some sleep – although the only view for the rear pilot was through the side windows. In July 1932 they flew a similar route and were making good time until over Russia when the roof hatch blew off and damaged the fin. In the resulting crash, the pilots were unhurt but the Vega was wrecked.

In 1933, Wiley tested the latest model of the Sperry autopilot – he called it ‘Mechanical Mike’- and also installed a gyro compass. He had the engine rebuilt with higher-compression pistons and a variable-pitch propeller fitted. Fuel tanks were installed in the cabin so that he could pump fuel between them to control the CG position. An aerial appeared on the fin. It was for a new type of radio which the US Army installed for Wiley (some details of its operation were still on the secret list). The radio was an Automatic Direction Finder that could indicate the direction of a radio beacon. A few navigation beacons were being set up, only in the USA. Elsewhere the ADF would work equally well with commercial radio transmitters.

It soon became evident that Wiley intended to try to beat his own record and this time to fly solo. He added another special ‘instrument’. In his hand, he held a small lead ball which was attached to his finger by a string. If he fell asleep, his hand would relax, the ball would fall and the jerk would wake him.

All this activity didn’t go unnoticed by Griffin and Mattern. They had repaired their Vega and tossed a coin to decide who would challenge Wiley to be first in a solo round-the–world flight. Jimmy Mattern won the toss and hastily completed his preparations. He left New York on 3rd June1933. Just under 24 hours later he landed in Norway, although, until he climbed down from the cockpit, he thought it was Scotland. After that, he made good progress across Siberia. Then he disappeared. He had been two hours from Nome in Alaska when his engine failed. He force landed safely in uninhabited wilderness with no sign of rescue. There was a river nearby, so he built a raft and drifted downstream. It was two weeks before he came upon an Eskimo settlement and the world learned that he was safe.

Wiley was pleased to hear the news about Jimmy Matten and also relieved that the first the solo circumnavigation was yet to be completed. As before, he waited patiently in New York for the word of Dr Kimball. On 15th July the forecast seemed to be favourable and he climbed aboard Winnie Mae. He was wearing a smart double-breated suit, white shirt and blue tie. Not for him the showy breeches, helmet and goggles which other pilots wore. He was cheered on his way by 500 fans who had camped out for six weeks waiting for his departure.

Full to the brim with 645 gallons of fuel (87 octane for takeoff, 80 octane for cruise) the takeoff run took a long 29 seconds. Wiley headed off across the Atlantic, enjoying the luxury of his auto-pilot. Approaching Europe, he tuned in to the G2LO radio station at Manchester and was delighted to hear ‘a special broadcast for Wiley Post’. In the heavy cloud over Europe he detected a problem with the autopilot which became erratic. After 19 hours, 54 minutes he landed at Berlin, completing the first 3,942 mile direct flight between the capitals.

(The Atlantic was quite busy in 1933. On the day that Wiley left New York the 23 Savoia flying boats of Italo Balbo’s formation arrived in Chicago. Later that month, Jim and Amy Mollison flew their DH84 Seafarer from Wales to a crash landing in Connecticut).

Whilst the Vega was being refuelled other mechanics tried, but failed to fix the autopilot. Wiley left Berlin for Novosibirsk. On the way, he discovered that he was short of some maps of Russia so he diverted to Königsberg. There a leak was traced in the autopilot’s oil supply line but no-one could repair it. Then the weather closed in and Wiley caught up with some much needed sleep.

He suffered from terrible weather over Russia and Siberia and had to land three times to check his position. He was now a whole day behind schedule although relieved that he’d been able to get the autopilot repaired at Novosibirsk. At Khabarovsk in Eastern Siberia he faced a 3,100 mile leg across 15,000 ft mountains and stretches of ocean to Fairbanks in Alaska. Jimmy Mattern, still on the ground there, helped with reports of local weather.

Wiley was by no means fresh and he was grateful for the autopilot helping him to penetrate the clouds. At last he reached Alaska. He circled the Nome radio station and headed east for Fairbanks. Then more trouble struck. He found that he couldn’t pick up any transmission from Fairbanks. Both his radio and ADF had stopped working. He was soon completely lost.

All this activity didn’t go unnoticed by Griffin and Mattern. They had repaired their Vega and tossed a coin to decide who would challenge Wiley to be first in a solo round-the–world flight. Jimmy Mattern won the toss and hastily completed his preparations. He left New York on 3rd June1933. Just under 24 hours later he landed in Norway, although, until he climbed down from the cockpit, he thought it was Scotland. After that, he made good progress across Siberia. Then he disappeared. He had been two hours from Nome in Alaska when his engine failed. He force landed safely in uninhabited wilderness with no sign of rescue. There was a river nearby, so he built a raft and drifted downstream. It was two weeks before he came upon an Eskimo settlement and the world learned that he was safe.

Wiley was pleased to hear the news about Jimmy Matten and also relieved that the first the solo circumnavigation was yet to be completed. As before, he waited patiently in New York for the word of Dr Kimball. On 15th July the forecast seemed to be favourable and he climbed aboard Winnie Mae. He was wearing a smart double-breated suit, white shirt and blue tie. Not for him the showy breeches, helmet and goggles which other pilots wore. He was cheered on his way by 500 fans who had camped out for six weeks waiting for his departure.

Full to the brim with 645 gallons of fuel (87 octane for takeoff, 80 octane for cruise) the takeoff run took a long 29 seconds. Wiley headed off across the Atlantic, enjoying the luxury of his auto-pilot. Approaching Europe, he tuned in to the G2LO radio station at Manchester and was delighted to hear ‘a special broadcast for Wiley Post’. In the heavy cloud over Europe he detected a problem with the autopilot which became erratic. After 19 hours, 54 minutes he landed at Berlin, completing the first 3,942 mile direct flight between the capitals.

(The Atlantic was quite busy in 1933. On the day that Wiley left New York the 23 Savoia flying boats of Italo Balbo’s formation arrived in Chicago. Later that month, Jim and Amy Mollison flew their DH84 Seafarer from Wales to a crash landing in Connecticut).

Whilst the Vega was being refuelled other mechanics tried, but failed to fix the autopilot. Wiley left Berlin for Novosibirsk. On the way, he discovered that he was short of some maps of Russia so he diverted to Königsberg. There a leak was traced in the autopilot’s oil supply line but no-one could repair it. Then the weather closed in and Wiley caught up with some much needed sleep.

He suffered from terrible weather over Russia and Siberia and had to land three times to check his position. He was now a whole day behind schedule although relieved that he’d been able to get the autopilot repaired at Novosibirsk. At Khabarovsk in Eastern Siberia he faced a 3,100 mile leg across 15,000 ft mountains and stretches of ocean to Fairbanks in Alaska. Jimmy Mattern, still on the ground there, helped with reports of local weather.

Wiley was by no means fresh and he was grateful for the autopilot helping him to penetrate the clouds. At last he reached Alaska. He circled the Nome radio station and headed east for Fairbanks. Then more trouble struck. He found that he couldn’t pick up any transmission from Fairbanks. Both his radio and ADF had stopped working. He was soon completely lost.

Looking for somewhere to land he spotted an airstrip at the small town of Flat. It was short - only 700 feet long and ominously, at the end was a ditch. With the lightest of landings and heavy braking he nearly made it. The right landing gear dropped in the ditch and crumpled, the tail came up and the propeller bit into the earth. Wiley was physically uninjured but exhausted and demoralised.

The workers of the Flat Mining Company rallied round. They rigged a derrick to hoist Winnie Mae out of the ditch. Wiley contacted Joe Crosson, a friend in Fairbanks, to bring him a replacement propeller.

The workers of the Flat Mining Company rallied round. They rigged a derrick to hoist Winnie Mae out of the ditch. Wiley contacted Joe Crosson, a friend in Fairbanks, to bring him a replacement propeller.

Whilst Wiley slept Joe and the miners worked through the night to repair the Vega. At daybreak the refreshed Wiley and repaired Winnie left Flat for Fairbanks and fuel. In a hurry to get away he had to wait there another eight hours before bad weather cleared at his next destination, Edmonton in Canada. When he did leave, he flew through the storms over the Rockies, at times being forced up to 20,000 feet.

After Edmonton, the last 2000 mile leg was almost downhill. In calm skies, with a working autopilot, Wiley allowed himself to doze, relying on his safety alarm – the lost lead ball replaced by a small wrench on the string.

After Edmonton, the last 2000 mile leg was almost downhill. In calm skies, with a working autopilot, Wiley allowed himself to doze, relying on his safety alarm – the lost lead ball replaced by a small wrench on the string.

He landed at New York in the dark and when he taxied up to the floodlit terminal buildings Winnie Mae was engulfed by a crowd of 50,000 people. He had encircled the globe in 7 days, 18 hours, 49½ minutes, beating his previous record (with Harold Gatty) by more than 21 hours. Wiley was annoyed. He wanted to do it in less than 7 days. Nevertheless, not only had he flown the fastest circumnavigation but he had done it twice – and his record time was to stand unchallenged until 1947, when the circumstances were entirely different.

With a radio reporter standing on the steps, Wiley is crawling back onto the

wing before sliding to the ground.

With a radio reporter standing on the steps, Wiley is crawling back onto the

wing before sliding to the ground.

Wiley was congratulated by Italo Balbo and his team of pilots. He visited Jim and Amy Mollison in hospital. However, in this august company of aviators his achievement was seen to stand above all others and he was cheered on his ticker tape parade and invited to visit the President in the White House. He was awarded the Gold Medal of the Federation Aeronautique Internationale. The only other American to be so honoured was Charles Lindbergh.

The usual round of appearances and speeches took Wiley around the country and it didn’t always go well. Two months after the flight, he was invited to Quincy, Illinois. Introducing him, the Mayor forgot his name ‘. . the intrepid flyer, Mr . . .’. He had to lean over and ask Wiley what it was. When Wiley rose he said ‘It’s a great honour to be asked to speak to the representatives of this great city of . . .’ and he turned to the Mayor to ask its name. Not everyone enjoyed the joke. Shortly after he took off the following morning the engine failed over a heavily wooded area. Wiley was slightly injured in the crash landing and had to spend a few days in hospital. His engineer came to retrieve the damaged Winnie Mae. He was astonished to find five and a half gallons of water in the fuel tanks.

Wiley Post reviewed his record breaking flights and considered how they could have been better. Winnie Mae was becoming outclassed by some of the newer planes being produced. Even so, he thought he could get more speed out of her by flying higher where the winds were stronger. When he heard of the MacRobertson Air Race, to be flown in October 1934, he began planning to put his theory into practice.

High speed winds had been detected by studying the movement of visible clouds but there was scant knowledge of what we now know as the jet stream. Wiley had experienced their effect when he had flown high to escape bad weather. He determined to learn more about them.

Flying at 30,000 or 40,000 feet would need more than oxygen. Some form of pressurisation was essential. Well aware that he had no hope of pressurising the wooden fuselage of the Vega he decided to develop a pressure suit for himself. His friend, Jimmy Doolittle, suggested he should contact the B F Goodrich tyre company. Wiley asked them to make a rubber suit to which could be pressured to 5lbs per square inch. This would make flying at 27,000 feet the equivalent of 5,000 feet. They did it for the remarkably low price of $75.

The usual round of appearances and speeches took Wiley around the country and it didn’t always go well. Two months after the flight, he was invited to Quincy, Illinois. Introducing him, the Mayor forgot his name ‘. . the intrepid flyer, Mr . . .’. He had to lean over and ask Wiley what it was. When Wiley rose he said ‘It’s a great honour to be asked to speak to the representatives of this great city of . . .’ and he turned to the Mayor to ask its name. Not everyone enjoyed the joke. Shortly after he took off the following morning the engine failed over a heavily wooded area. Wiley was slightly injured in the crash landing and had to spend a few days in hospital. His engineer came to retrieve the damaged Winnie Mae. He was astonished to find five and a half gallons of water in the fuel tanks.

Wiley Post reviewed his record breaking flights and considered how they could have been better. Winnie Mae was becoming outclassed by some of the newer planes being produced. Even so, he thought he could get more speed out of her by flying higher where the winds were stronger. When he heard of the MacRobertson Air Race, to be flown in October 1934, he began planning to put his theory into practice.

High speed winds had been detected by studying the movement of visible clouds but there was scant knowledge of what we now know as the jet stream. Wiley had experienced their effect when he had flown high to escape bad weather. He determined to learn more about them.

Flying at 30,000 or 40,000 feet would need more than oxygen. Some form of pressurisation was essential. Well aware that he had no hope of pressurising the wooden fuselage of the Vega he decided to develop a pressure suit for himself. His friend, Jimmy Doolittle, suggested he should contact the B F Goodrich tyre company. Wiley asked them to make a rubber suit to which could be pressured to 5lbs per square inch. This would make flying at 27,000 feet the equivalent of 5,000 feet. They did it for the remarkably low price of $75.

Made of double thickness rubberised parachute fabric, the two-piece suit was held together at the waist by a metal belt. Oxygen would be supplied separately from a bottle of liquid oxygen. The aluminium helmet had a double glazed visor, to combat condensation, and a small plate could be opened for unpressurised conversation and feeding.

The suit was tested by Goodrich simply by inflating it to check for leaks then delivered to Wiley. He took it to Wright Field where the US Army had a decompression chamber normally used for testing altimeters. The suit seemed to work but it was evident that Wiley’s original specification would have to be more rigorous for effective use at higher altitudes. When the pressure was raised to more than 5 lbs per sq. in. it had leaked at joints and at the waist.

The army’s engineers and a doctor got interested and the design was modified using a new helmet with a screw-in circular face plate. In a significant improvement they added flexible ring joints at knees and elbows. There were inlets for both the pressurising air and oxygen.

The suit was tested by Goodrich simply by inflating it to check for leaks then delivered to Wiley. He took it to Wright Field where the US Army had a decompression chamber normally used for testing altimeters. The suit seemed to work but it was evident that Wiley’s original specification would have to be more rigorous for effective use at higher altitudes. When the pressure was raised to more than 5 lbs per sq. in. it had leaked at joints and at the waist.

The army’s engineers and a doctor got interested and the design was modified using a new helmet with a screw-in circular face plate. In a significant improvement they added flexible ring joints at knees and elbows. There were inlets for both the pressurising air and oxygen.

The second suit was ready for testing in July 1934. It was a hot and humid day when Wiley tried it on. The two piece design had been abandoned and the ‘entrance’ was a single slot near the neck. He had also put on a little weight since the first measurements were made. It was a real struggle and soon he became overheated and trapped. The longer he was in, the tighter it became. In the end, he had to be cut out of the suit.

The repair and rebuilding was quickly done and the opportunity was taken for further modifications. Rather than pressurise the suit by air from the engine’s supercharger (which could have been fatal if the engine stopped) Suit No 3 would be pressurised solely by oxygen. It was also made a little larger to be a better fit. Tests were made in the decompression chamber, initially to 21,000 feet then to increasing heights. The suit needed only minor modifications.

Wiley pulled together other research into high altitude living. He found that in reduced pressure the radio’s condensers could suffer from ‘frequency drift’ and that the engine’s ignition system needed to be sealed against ‘arcing’. As time went on, Wiley abandoned all thoughts of entering the MacRobertson race and looked towards the world altitude record. In 1932, Cyril Uwins had reached 43,976 feet in an open-cockpit Vickers Vespa biplane. This record was broken by Renato Donati of the Italian Air Force in a Caproni 114, also an open cockpit biplane on his 18th attempt. He reached 47,352 feet but suffered so badly from the cold and lack of oxygen that he had to be lifted from the cockpit and carried off to hospital. Wiley looked forward to a happier experience in his pressurised suit.

The repair and rebuilding was quickly done and the opportunity was taken for further modifications. Rather than pressurise the suit by air from the engine’s supercharger (which could have been fatal if the engine stopped) Suit No 3 would be pressurised solely by oxygen. It was also made a little larger to be a better fit. Tests were made in the decompression chamber, initially to 21,000 feet then to increasing heights. The suit needed only minor modifications.

Wiley pulled together other research into high altitude living. He found that in reduced pressure the radio’s condensers could suffer from ‘frequency drift’ and that the engine’s ignition system needed to be sealed against ‘arcing’. As time went on, Wiley abandoned all thoughts of entering the MacRobertson race and looked towards the world altitude record. In 1932, Cyril Uwins had reached 43,976 feet in an open-cockpit Vickers Vespa biplane. This record was broken by Renato Donati of the Italian Air Force in a Caproni 114, also an open cockpit biplane on his 18th attempt. He reached 47,352 feet but suffered so badly from the cold and lack of oxygen that he had to be lifted from the cockpit and carried off to hospital. Wiley looked forward to a happier experience in his pressurised suit.

Wiley walks towards Winnie Mae. The faceplate is not yet fitted and he’s crouching because the suit is made to be comfortable in the sitting position.

Winnie Mae had been stripped of all unnecessary equipment, even the engine starter. A special carburettor was fitted and the 7:1 supercharger replaced by a 13:1 unit. Phillips Petroleum developed some special 87 octane fuel. Wiley had signed a ‘release’ absolving suppliers from all responsibility from any event or failure.

The first serious flight was in late November 1934. Wiley was ‘approaching 48,000 feet’ when he was distracted by some trouble with an oxygen valve and running low on fuel. A couple of weeks later, he took off again. This time, his altimeter stuck at 35,000 feet. He continued climbing and ran into the real object of all his experiments and suit-building. Whilst heading west he checked his groundspeed and it was down to just 50 mph. He calculated that the windspeed was near 200 mph. The suit was working well. He was warm and entirely comfortable. He had found - and could use - exactly what would bring him race wins and distance records.

Overcome with euphoria he stayed up too long and ran out of fuel. At least he had enough height and time to select a suitable airfield for a dead stick landing. The press claimed that he had reached 50,000 feet. Wiley couldn’t confirm that. His altimeter had stuck and the barographs which would have allowed him to claim a record had both failed.

The altitude record was entirely incidental to Wiley. He planned to set distance and speed records – transcontinent, 6 hours, New York to London, 12 hours – he said. With only one landing in prospect (at the destination) he could reduce weight and drag by dropping the undercarriage after take-off. A wooden skid, sheathed with a metal plate was fitted under the fuselage and a smaller tail skid fitted. The propeller blades were painted red and green. Wiley would stop the engine before landing and crank the blades to the proper horizontal position so that the counterweight for the conrods would be in the lower position at the bottom of the engine.

Overcome with euphoria he stayed up too long and ran out of fuel. At least he had enough height and time to select a suitable airfield for a dead stick landing. The press claimed that he had reached 50,000 feet. Wiley couldn’t confirm that. His altimeter had stuck and the barographs which would have allowed him to claim a record had both failed.

The altitude record was entirely incidental to Wiley. He planned to set distance and speed records – transcontinent, 6 hours, New York to London, 12 hours – he said. With only one landing in prospect (at the destination) he could reduce weight and drag by dropping the undercarriage after take-off. A wooden skid, sheathed with a metal plate was fitted under the fuselage and a smaller tail skid fitted. The propeller blades were painted red and green. Wiley would stop the engine before landing and crank the blades to the proper horizontal position so that the counterweight for the conrods would be in the lower position at the bottom of the engine.

Hand starting at Burbank. Note how smoothly the skid is fitted below the fuselage. The intake above the engine is for the supercharger.

Everything was ready on 22nd February 1935 when Wiley took off from Burbank for New York. He dropped the gear and climbed into the clouds. Trouble struck early. After 31 minutes, the engine began to throw oil. Wiley prepared to land at Muroc Dry Lake, still loaded with 300 gallons of fuel..

Everything was ready on 22nd February 1935 when Wiley took off from Burbank for New York. He dropped the gear and climbed into the clouds. Trouble struck early. After 31 minutes, the engine began to throw oil. Wiley prepared to land at Muroc Dry Lake, still loaded with 300 gallons of fuel..

It was so skilfully done that it wasn’t heard by a man standing 400 yards away. His back was turned and the first he knew was when a ‘man in a Buck Rogers suit’ asked for help to undo the wing nuts on the back of his helmet.

It wasn’t a broken oil line that had brought Winnie down. On examination they found another incidence of sabotage. A quantity of emery dust had been placed in the supercharger’s intake. When this was sucked in it played havoc with the engine’s internals.

It wasn’t a broken oil line that had brought Winnie down. On examination they found another incidence of sabotage. A quantity of emery dust had been placed in the supercharger’s intake. When this was sucked in it played havoc with the engine’s internals.

Three weeks later, with a rebuilt engine, Wiley tried again. All went well until he passed Cleveland. Then his oxygen supply failed and he turned back to land at Cleveland. The good news was that he had averaged a ground speed of 279 mph, almost 100 mph faster than Winnie’s maximum speed. He had ridden the jet stream.

A third attempt ended after 1760 miles when the supercharger broke. Wiley was encouraged to try yet again. This time he landed at Wichita with a broken piston. Obviously, it was high time for Winnie’s retirement and she was bought by the Smithsonian Institution. She was tidied up and the normal undercarriage replaced. She sits there to this day, a tribute to Wiley’s circumnavigations and his pioneering work in developing the first practical pressure suit.

Wiley looked round for another aeroplane. In a dealer’s yard he found a fuselage from a damaged Lockheed Orion that had been in Service with TWA for two years. In the same yard was a wing rather longer than the standard Orion wing. It was from a Lockheed Explorer. This had been built as a special for long distance flights and crashed in Panama, writing off the fuselage. It was a cheap way to get a new plane - Wiley was rather short of funds after his pressure suit experiments. When Lockheed learned that he intended to produce a hybrid of the two parts they did not recommend it and made it clear that they would play no part in the rebuild.

A third attempt ended after 1760 miles when the supercharger broke. Wiley was encouraged to try yet again. This time he landed at Wichita with a broken piston. Obviously, it was high time for Winnie’s retirement and she was bought by the Smithsonian Institution. She was tidied up and the normal undercarriage replaced. She sits there to this day, a tribute to Wiley’s circumnavigations and his pioneering work in developing the first practical pressure suit.

Wiley looked round for another aeroplane. In a dealer’s yard he found a fuselage from a damaged Lockheed Orion that had been in Service with TWA for two years. In the same yard was a wing rather longer than the standard Orion wing. It was from a Lockheed Explorer. This had been built as a special for long distance flights and crashed in Panama, writing off the fuselage. It was a cheap way to get a new plane - Wiley was rather short of funds after his pressure suit experiments. When Lockheed learned that he intended to produce a hybrid of the two parts they did not recommend it and made it clear that they would play no part in the rebuild.

The original Orion was registered N12283. Wiley had to accept the NR ‘Restricted’ category for the hybrid, limiting it to be flown by pilot and crew – i.e. no passengers.

It was unclear what Wiley intended to do with his plane. It appeared that he intended to go on holiday with his wife to Alaska and Siberia, to say ‘thank you’ for all the help he had been given in his record flights. He was also going to take his old friend Will Rogers. Rogers was an actor and humorist who also ran a newspaper column. He’d just finished an exhausting film and needed a break to refresh himself and his column. They arranged to meet in Seattle and Wiley ordered a set of floats for his plane – there were more lakes than landing strips in Alaska.

In Seattle, Mrs Post learned that the men were going to take their fishing, hunting and camping gear. She decided to do something more interesting at home. The floats didn’t arrive and Rogers, who was paying for the trip, was impatient to get started. He was taking his typewriter to write up his experiences for his column. Wiley hunted around and found a set of floats from a Ford Trimotor. They were big. A Trimotor weighed 13,000 lbs fully loaded. The Orion-Explorer weighed 5,400lbs. Wiley had them fitted anyway.

In Seattle, Mrs Post learned that the men were going to take their fishing, hunting and camping gear. She decided to do something more interesting at home. The floats didn’t arrive and Rogers, who was paying for the trip, was impatient to get started. He was taking his typewriter to write up his experiences for his column. Wiley hunted around and found a set of floats from a Ford Trimotor. They were big. A Trimotor weighed 13,000 lbs fully loaded. The Orion-Explorer weighed 5,400lbs. Wiley had them fitted anyway.

The hybrid had been a little nose heavy before the floats were fitted. Now it was decidedly nose heavy. A glide landing would not be possible. The hybrid needed the slipstream from the engine to make its controls effective. Wiley was concerned that, with the unmatched floats, he might be infringing the terms of his plane’s Restricted category. He was anxious to get on his way and away from the press.

On 6th August 1935, they set sail from Seattle for Alaska. At Juneau they visited friends, waited a few days for the weather to clear and went on to Dawson and Fairbanks. There they met Joe Crosson, who had helped Wiley after his arrival in the ditch at Flat. Joe was the Chief Pilot of Alaska Airways and didn’t like what he saw. He urged Wiley to get more appropriate floats or, at least rearrange the fitting of the oversized floats they had.

Will Rogers was keen to meet an old Alaskan character who lived in Barrow on the north coast. Joe couldn’t persuade the travellers to postpone the flight and gave them advice on the route which was rather roundabout so as to simplify navigation. Nevertheless, the flight went well although they were running low on fuel before they reached Barrow. They saw a settlement by a lake, so they alighted there to find out exactly where they were. It was a sealing camp run by a group of Eskimos.

They were pleased to see the fliers and pressed them to have some food. Rogers enjoyed the chat with the Eskimos, collecting material for his column. They found they were only 16 miles from Barrow and they probably stayed at the lake too long. The engine was no longer warm when they taxied out into the lake and floatplanes can’t be stopped to run up the engine. Wiley lined up into wind and opened the throttle. The plane frothed through the water, rose onto the step and lifted off. As it began to climb away, the engine suddenly stopped.

Will Rogers was keen to meet an old Alaskan character who lived in Barrow on the north coast. Joe couldn’t persuade the travellers to postpone the flight and gave them advice on the route which was rather roundabout so as to simplify navigation. Nevertheless, the flight went well although they were running low on fuel before they reached Barrow. They saw a settlement by a lake, so they alighted there to find out exactly where they were. It was a sealing camp run by a group of Eskimos.

They were pleased to see the fliers and pressed them to have some food. Rogers enjoyed the chat with the Eskimos, collecting material for his column. They found they were only 16 miles from Barrow and they probably stayed at the lake too long. The engine was no longer warm when they taxied out into the lake and floatplanes can’t be stopped to run up the engine. Wiley lined up into wind and opened the throttle. The plane frothed through the water, rose onto the step and lifted off. As it began to climb away, the engine suddenly stopped.

The nose dropped and the plane dived into the shallow water. There was the flare of a brief fire and when the spray settled, the spectators saw the Orion lying upside down with a broken fuselage and one wing detached. Wiley had been killed by the impact and Rogers was dead in the water.

The nation was stunned by the accident, rating Wiley Post’s achievements as greater than the more famous Lindbergh’s. His round the world flights were outstanding at the time and his enduring legacy is undoubtedly the development of the first effective pressure suit, frequently acknowledged by today’s astronauts.

The nation was stunned by the accident, rating Wiley Post’s achievements as greater than the more famous Lindbergh’s. His round the world flights were outstanding at the time and his enduring legacy is undoubtedly the development of the first effective pressure suit, frequently acknowledged by today’s astronauts.