Signora essere buona (Oct 2014)

The story of ‘Lady Be Good’ – the Liberator which disappeared into the North African desert after a bombing raid – is well known. Less well known is that, two years previously, another event occurred, with remarkable parallels, involving an Italian Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 torpedo bomber.

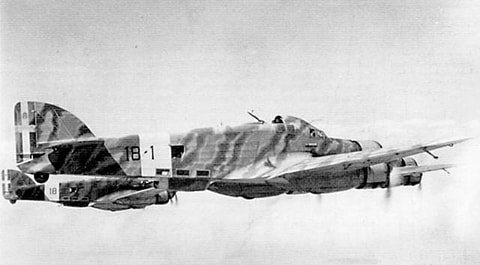

The SM 79 Spaviero (Sparrowhawk) first flew in 1934. It was hoped to enter the prototype in the MacRobertson race to Australia but it was not ready in time. Nevertheless, the fast three-engined bomber made its mark by setting several speed records. Less creditably, it was used alongside the German Condor Legion in the bombing raids of the Spanish Civil War. By 1940, when Italy entered the war, over 600 were in service as the Regia Aeronautica’s most numerous bomber using either normal bombs or torpedoes. Powered by three 740 hp Alfa-Romeo engines it could reach 270 mph and had an endurance of 4hrs 30 mins. The five or six crew members had five machine guns for defence but all had restricted fields of fire. Curiously, there was no intercom between the pilot and the bomb aimer.

The SM 79 Spaviero (Sparrowhawk) first flew in 1934. It was hoped to enter the prototype in the MacRobertson race to Australia but it was not ready in time. Nevertheless, the fast three-engined bomber made its mark by setting several speed records. Less creditably, it was used alongside the German Condor Legion in the bombing raids of the Spanish Civil War. By 1940, when Italy entered the war, over 600 were in service as the Regia Aeronautica’s most numerous bomber using either normal bombs or torpedoes. Powered by three 740 hp Alfa-Romeo engines it could reach 270 mph and had an endurance of 4hrs 30 mins. The five or six crew members had five machine guns for defence but all had restricted fields of fire. Curiously, there was no intercom between the pilot and the bomb aimer.

A squadron of SM 79s was based at Berka, near Benghazi in Libya. On 20th April, 1941 Captain Oscar Cimolini flew his Spaviero from Italy to join the squadron. Although he was completely unfamiliar with the area on the very next day he was sent off on his first operation. At 17.25 he took off to follow Lt Robone to attack a British convoy off Crete. At about 20.00 Robone launched his torpedo which struck an 8,000 ton steamer. The Spavieros turned away into the darkness to head for Benghazi. Robone returned to his base but nothing more was seen or heard of Cimolini and his aircraft. Searches found nothing and the crew were listed as missing in action.

Nineteen years later, on 21 July 1960, a geologist came across a skeleton half buried in the desert. Nearby they found uniform buttons, a half litre water bottle, an aircraft compass, binoculars, two watches, a pistol which had fired one shot, scraps of German and Italian newspapers and, most significantly, a set of keys. On the plate with the keys was a stamp - ‘S-79-MM 23881’. Searches in the records showed that MM 23881 was the serial number of Cimolini’s bomber and the skeleton was identified as that of Sgt. Maj. Giovanni Romanini, one of the gunners.

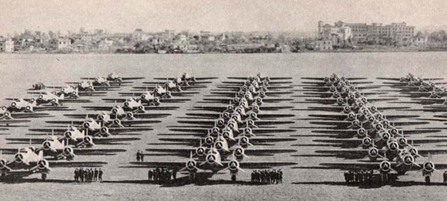

SM 79 ‘Signora essere buona’

SM 79 ‘Signora essere buona’

Four months later, another survey team discovered the wrecked SM79. It was 90 kms south of where Romanini’s body had been found and 500kms away from its airfield. Nearby were the remains of the other four crew members. Examination of the wreckage gave few clues to the sequence of events but it appears that the plane was force-landed successfully and the crew were able to get out, although probably with injuries. Romanini was fit enough to walk for help and set off northwards. He almost made it. His body was found just a few kilometres from a well used track.

Unlike ‘Lady Be Good’ the wreck was not recovered but the lost Spaviero’s story is suitably commemorated in Milan’s Volandia Museum of Flight where a diorama has been set up showing the skeleton of an SM 79 resting on the sand together with the cockpit of another which crashed ‘normally’ in the Lebanon.

Before we leave the disappearing Sparrows – there’s another parallel tale.

You’ll remember Aphrodite, the US experiments to convert old B-17s into explosive filled drones. Well – Col. Ferdinando Raffaelli had the same bright idea - he called it Operation Canary. Planning to attack one of the Allied Gibraltar to Malta convoys he took an old SM 79 and packed it with 1000 kg of explosives and radio-activated controls.

His moment arrived when Operation Pedestal left Gibraltar in August 1942 to relieve a starving Malta. 4 carriers, 2 battleships, 39 cruisers and destroyers shepherded 14 merchant ships through the Med. Raffaeli’s canary, along with 6 surface ships, 11 subs, 14 torpedo boats and lots of Luftwaffe was ready to knock the British off their pedestal. Painted overall yellow (that’s the ‘canary’ bit), to be easily followed by the controlling aircraft, the SM79 was flown by Major Mario Badii. They pointed at the convoy at their chosen altitude of 500 metres and, when everything was working properly, Badii baled out into the Med. and Raffaeli, in the following SM79, took control.

Then, inevitably, there was a problem. The transmitter stopped working. In the chaotic attack on the ships, it’s unlikely that anyone noticed the yellow bomber cruising steadily along and ignoring all the activity below.

Raffaeli turned for home and the Canary blasted out a small nest on a rockface in the Atlas mountains.

You’ll remember Aphrodite, the US experiments to convert old B-17s into explosive filled drones. Well – Col. Ferdinando Raffaelli had the same bright idea - he called it Operation Canary. Planning to attack one of the Allied Gibraltar to Malta convoys he took an old SM 79 and packed it with 1000 kg of explosives and radio-activated controls.

His moment arrived when Operation Pedestal left Gibraltar in August 1942 to relieve a starving Malta. 4 carriers, 2 battleships, 39 cruisers and destroyers shepherded 14 merchant ships through the Med. Raffaeli’s canary, along with 6 surface ships, 11 subs, 14 torpedo boats and lots of Luftwaffe was ready to knock the British off their pedestal. Painted overall yellow (that’s the ‘canary’ bit), to be easily followed by the controlling aircraft, the SM79 was flown by Major Mario Badii. They pointed at the convoy at their chosen altitude of 500 metres and, when everything was working properly, Badii baled out into the Med. and Raffaeli, in the following SM79, took control.

Then, inevitably, there was a problem. The transmitter stopped working. In the chaotic attack on the ships, it’s unlikely that anyone noticed the yellow bomber cruising steadily along and ignoring all the activity below.

Raffaeli turned for home and the Canary blasted out a small nest on a rockface in the Atlas mountains.