Slingsby – and its Arrows of Fortune (Jan 2018)

It’s only a little factory in rural Yorkshire and yet one of its ordinary and least sophisticated products had a major influence on the number of home-grown pilots in commercial airlines. The spark which launched many an airborne career was solo flight in a Mark 3 – three four-minute circuits in an Air Cadets basic training glider, the Slingsby T-31. However, Slingsby’s story is not entirely about gliders and gliding, though its roots are firmly based there.

Fred Slingsby was born in 1894 and grew up in Scarborough where he started working life as a carpenter, like his father. His skills served him well when he went to war and found himself in the Royal Flying Corps, servicing and repairing aeroplanes in France. His training as a gunner got him into the rear seat of a biplane, ready to fend off any enemy trying to interfere with the vital job of reconnaissance. But he had had no training for the event which won him a Military Medal. His pilot was killed by a too-close burst of Archie. Fred left his gun and managed to take control of the aeroplane, fly it home and land it safely.

He left the RAF in 1920 and bought a partnership in a small furniture factory in Scarborough, Slingsby, Russell and Brown. In 1930, the Austrian Robert Kronfeld visited England and demonstrated the capabilities of his sailplane. The impact of this flight launched the gliding movement in England. On the basis of his ‘piloting’ experience, Fred joined in, became a founder member of the Scarborough Gliding Club and built gliders for the club. His workmanship drew the attention of some wealthier members of the London Gliding Club including Philip Wills, who ran a shipping company in the City. He wanted an advanced sailplane built. Slingsby agreed, though his workshop was a number of small buildings and the only space long enough to build the wing was a corridor.

To promote gliding (only the London Club at Dunstable had any stability) Wills helped to establish the Yorkshire Gliding Club on an excellent site at Sutton Bank. The principal support came from one of the sponsors of Fred’s furniture factory. Major Jack Shaw had a little airfield near his home in Kirbymoorside, a small town in a fold of the Yorkshire moors near Sutton Bank. To give employment to the townspeople he offered Fred a small factory there and serious glider manufacture began in 1934.

Slingsby had built a two-seat glider, a German designed Falcon 3, which helped to introduce many people to gliding – people who were not prepared to follow the usual route of months of building primary gliders then spending most of their time dragging them about rough fields and pulling bungee ropes to launch other on seconds-long hops.

Fred Slingsby was born in 1894 and grew up in Scarborough where he started working life as a carpenter, like his father. His skills served him well when he went to war and found himself in the Royal Flying Corps, servicing and repairing aeroplanes in France. His training as a gunner got him into the rear seat of a biplane, ready to fend off any enemy trying to interfere with the vital job of reconnaissance. But he had had no training for the event which won him a Military Medal. His pilot was killed by a too-close burst of Archie. Fred left his gun and managed to take control of the aeroplane, fly it home and land it safely.

He left the RAF in 1920 and bought a partnership in a small furniture factory in Scarborough, Slingsby, Russell and Brown. In 1930, the Austrian Robert Kronfeld visited England and demonstrated the capabilities of his sailplane. The impact of this flight launched the gliding movement in England. On the basis of his ‘piloting’ experience, Fred joined in, became a founder member of the Scarborough Gliding Club and built gliders for the club. His workmanship drew the attention of some wealthier members of the London Gliding Club including Philip Wills, who ran a shipping company in the City. He wanted an advanced sailplane built. Slingsby agreed, though his workshop was a number of small buildings and the only space long enough to build the wing was a corridor.

To promote gliding (only the London Club at Dunstable had any stability) Wills helped to establish the Yorkshire Gliding Club on an excellent site at Sutton Bank. The principal support came from one of the sponsors of Fred’s furniture factory. Major Jack Shaw had a little airfield near his home in Kirbymoorside, a small town in a fold of the Yorkshire moors near Sutton Bank. To give employment to the townspeople he offered Fred a small factory there and serious glider manufacture began in 1934.

Slingsby had built a two-seat glider, a German designed Falcon 3, which helped to introduce many people to gliding – people who were not prepared to follow the usual route of months of building primary gliders then spending most of their time dragging them about rough fields and pulling bungee ropes to launch other on seconds-long hops.

Fred prepares to take up a passenger in the Falcon 3. A trousered Amy Johnson looks on as Fred kneels by the cockpit of a Slingsby Kite.

(When Amy Johnson arrived in Darwin on her historic light to Australia in 1930, one of the cables of congratulation came from Scarborough Gliding Club. She was invited to become the club’s president.Being a proud Yorkshire lass, she cabled back ‘Honoured to accept’).

Soon, Slingsby Sailplanes were producing the majority of the gliders being flown in British clubs, from basic trainers, to increasingly high performance sailplanes - the Kirby Kite, the Gull (the first glider to soar across the Channel), Gull 2 and 3. Jack Shaw thought that they deserved to be in better factory buildings. He learned that the London and North Eastern Railways were selling off their carriage washing sheds at Neasden. Shaw had these transported to Kirbymoorside and re-erected with stylish buttressed walls. The new factory opened, with somewhat muted celebration, on 4th September 1939.

Although the outbreak of war on the day before the factory’s opening had grounded all civilian gliders Slingsby were soon busy building rudders for Avro Ansons, the first of several contracts for wooden components for many aeroplanes, including Mosquitos. A special order was for another glider.

(When Amy Johnson arrived in Darwin on her historic light to Australia in 1930, one of the cables of congratulation came from Scarborough Gliding Club. She was invited to become the club’s president.Being a proud Yorkshire lass, she cabled back ‘Honoured to accept’).

Soon, Slingsby Sailplanes were producing the majority of the gliders being flown in British clubs, from basic trainers, to increasingly high performance sailplanes - the Kirby Kite, the Gull (the first glider to soar across the Channel), Gull 2 and 3. Jack Shaw thought that they deserved to be in better factory buildings. He learned that the London and North Eastern Railways were selling off their carriage washing sheds at Neasden. Shaw had these transported to Kirbymoorside and re-erected with stylish buttressed walls. The new factory opened, with somewhat muted celebration, on 4th September 1939.

Although the outbreak of war on the day before the factory’s opening had grounded all civilian gliders Slingsby were soon busy building rudders for Avro Ansons, the first of several contracts for wooden components for many aeroplanes, including Mosquitos. A special order was for another glider.

A small unit had been established at Worth Matravers in Dorset to find out whether wooden gliders would be detected by radar. All gliders have many small metal parts so Slingsby was asked to build one of his Kite sailplanes entirely of wood. The ‘secret’ non-metallic Kite had all its control wires replaced by wooden rods. It was still detected by radar though not as easily as the gliders with metal components.

The Air Ministry drew up a specification for a proposed assault glider, intending that it would be released some distance from the target for a long silent approach. Slingsby responded with the Hengist, to carry 14 troops. The landing loads were to be taken by an inflatable rubber bag. Only fourteen were produced. The specification was modified and production orders went to the larger Horsa.

Slingsby also built the Baynes Bat. Leslie Baynes conceived a plan to carry a tank into action under a 100 ft span glider wing. A one third sized prototype was tested by Flt Lt Robert Kronfeld, the very man who had inspired Britain to glide in 1930. The tests were entirely successful but the project came to naught, largely because of the lack of a suitable tank.

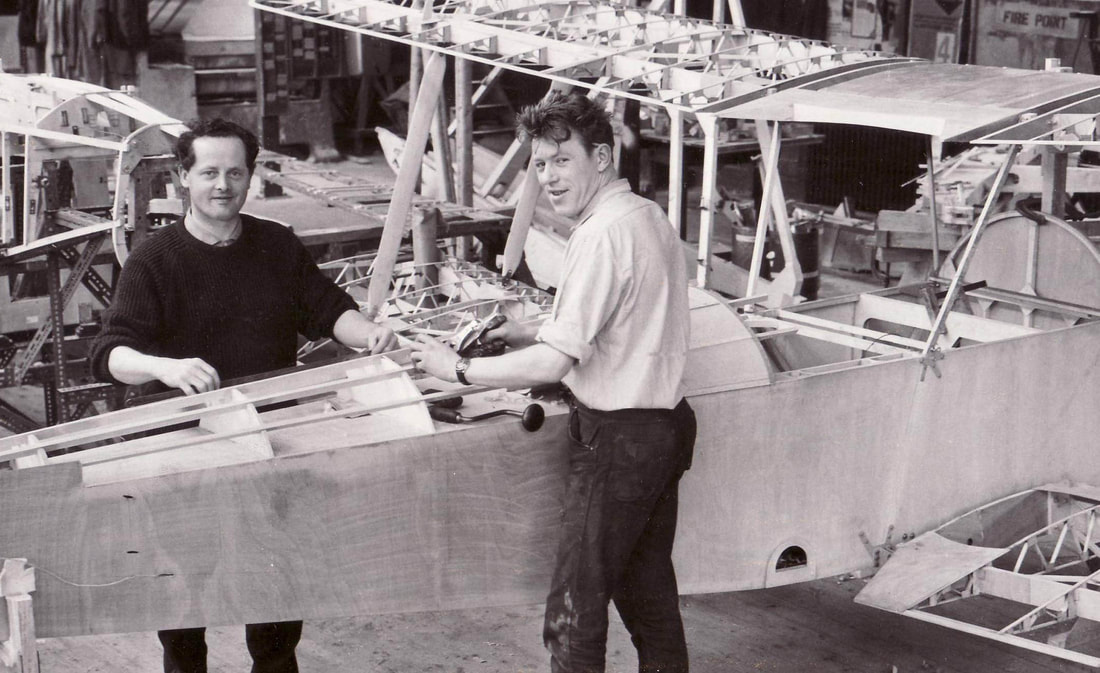

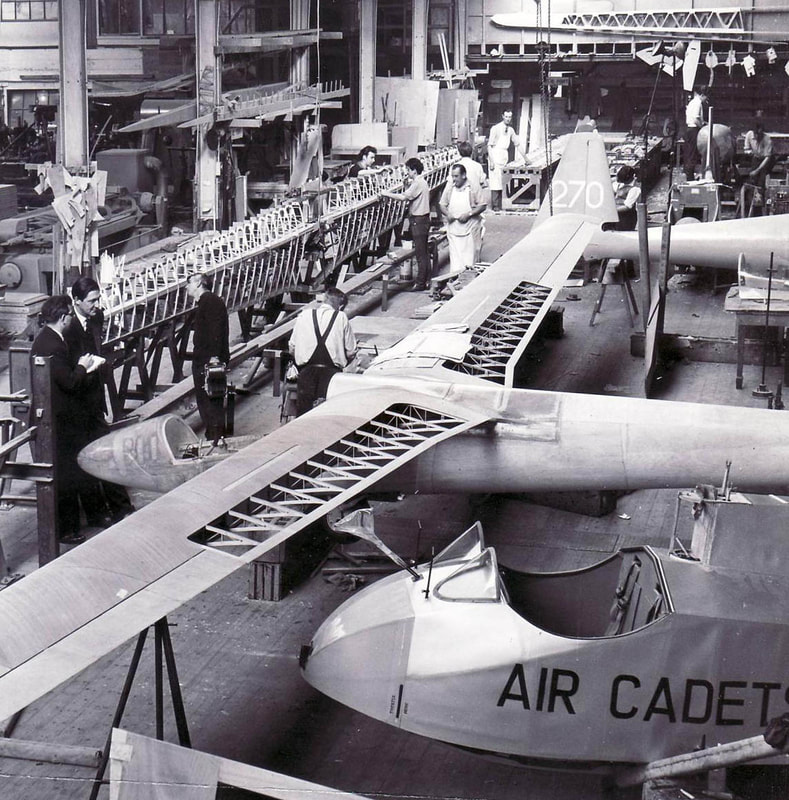

In 1941 the Air Defence Cadet Corps was restructured as the Air Training Corps. It was to be provided with gliding training, initially using a few requisitioned civilian gliders. Far too few for the large number of gliding schools established (87 by 1945), so Slingsby got an order for his T. 7 Kirby Kadet single seat trainer, which had first flown in 1935. Over 300 properly spelled Cadet Mk 1s were built and kept the factory busy throughout the war.

Slingsby later added the Mk. 2, the Tutor, with a slightly larger wing.

Slingsby later added the Mk. 2, the Tutor, with a slightly larger wing.

When the war ended, many in the aircraft industry expected that there would be a large market for small aircraft for all those trained pilots who would want to carry on flying in peaceful skies. It didn’t happen, but Slingsby was prepared with a really cheap aeroplane. He modified the Tutor by raising the wing to squeeze in a cockpit underneath it and hung a 25 or 40 hp engine on the nose. The Motor Tutor was demonstrated around the clubs and performed at air displays, frolicking about at low level and turning tightly, all within the airfield boundary.

The Motor Tutor generated little interest in sales and there was some difficulty in getting it certified by the Air Registration Board. It all seemed a dead loss until Fred salvaged some value from the project by abandoning the engine and putting the front cockpit back on the nose – an instant two seat glider trainer. It was adopted by the Air Training Corps and many other training organisations across the world. Over two hundred of the Cadet Mk 3s were sold. It was no good as a soaring machine but it was an excellent trainer. In appears in many pilots’ logbooks, recording their first solo flight.

Club gliding flourished and competitions increased demand for better performing sailplanes. Slingsby updated his pre-war Gull design and entered two in the 1948 international competition in Switzerland. They did well enough to justify further development. Fred designed a new wing of 18 metre span. The Sky was finished in time to be exhibited in the 1951 Festival of Britain. It proved to be very successful. In the 1954 World Championships in Spain, Philip Wills flew it to became World Champion. Other Skys (Skies?) were in 3rd and 4th places.

In 1955, Major Shaw died. His shares in Slingsby Sailplanes had to be sold to settle death duties and there was a threat of a hostile takeover which could have closed the Kirbymoorside factory. A fund-raising campaign within the gliding movement raised sufficient money to set up the Shaw-Slingsby Trust, chaired by Philip Wills.

After the world beating Sky, came the Skylark and the Dart both using laminar flow wings. These needed careful profiling and are fine examples of Slingsby’s craftsmanship in wood.

After the world beating Sky, came the Skylark and the Dart both using laminar flow wings. These needed careful profiling and are fine examples of Slingsby’s craftsmanship in wood.

Fred Slingsby’s health started to deteriorate in 1962 and he retired two years later. His contribution to gliding was recognised by the awards of the Paul Tissandier Diploma by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale and Fellowship of the RAeS. He died peacefully in 1973 at the age of 77.

Other aircraft built at Kirbymoorside included the aerobatic Tipsy Nipper. Its production run was abruptly ended in November 1968 by a disastrous fire at the factory.

The damage was severe enough to force the company into receivership. It was bought by the Vickers Marine Group. The factory was re-built and production of gliders and small aircraft resumed with increasing use of GRP.

Sailplane design and building materials had moved on, with German designers leading the field. Slingsby took out a licence to build a German Glasflugel glider and it was successfully marketed as the Kestrel. In an attempt to catch up, the 15 metre span Vega was designed and built. Although using advanced construction methods with a carbon fibre wing spar, it was not a great success.

At the time, the factory was busy producing four miniature submarines and other marine components. The Vickers management were never seriously interested in gliders; they made too little profit. Insufficient time and resources were made available to sort out all the Vega’s bugs and redesign tweaks before the scheduled launch date at the 1978 World Championships. It did not make a good impression. Although most of its faults were rectified, the Vega was never seen as a competitive sailplane. Its reputation was not enhanced when an Italian pilot had to bail out when the wings broke off.(the fault was traced to a sub-contractor’s faulty wing bolts). It was damned by a much quoted comment ‘Fly one? I wouldn’t walk under one.’ Production ended in 1982. It was the last glider to bear the Slingsby name.

Slingsby changed owners again. In 1979 Vickers were under pressure to reduce their overdraft. They sold the Kirbymoorside factory to British Underwater Engineering, a company providing diving services to the North Sea oil industry. It was renamed Slingsby Engineering.

Slingsby changed owners again. In 1979 Vickers were under pressure to reduce their overdraft. They sold the Kirbymoorside factory to British Underwater Engineering, a company providing diving services to the North Sea oil industry. It was renamed Slingsby Engineering.

In 1981, still very much in the aircraft business, Slingsby bought the development rights of the Fournier RF-6. The first models were built largely of wood. Re-engineered in plastics and renamed the Firefly, it sold well. It is an excellent aerobatic two-seat trainer and was adopted by the RAF. Other military users include Brazil, Jordan and, pictured right, the Hong Kong Auxiliary Air Force.

The Firefly attracted the attention of the USAF. At the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, the cadets were trained in the T-41 Mescalero (that’s the Cessna 172 to you and me). Those who performed well enough moved on later to the T-37 Tweet twin jet trainer. The old, much-used T-41 fleet was well overdue for replacement. The Firefly could do what the T-41 couldn’t i.e. introduce cadets to the aerobatic manoeuvres they would later start learning on the much more expensive to operate Tweet. The decision to buy the Firefly was not taken lightly. There was much opposition in Congress against buying a ‘little plasticky European plane’ but eventually, after a thorough test programme by a team of USAF test pilots, the contract was signed in 1992 for $34 million, no less. 56 Fireflies were ordered to be based at the Academy and 57 at a training group in Hondo, Texas. The model chosen was the T-67M, the most powerful with a Lycoming 260 hp engine. It would be the first all-composite aircraft operated by the USAF.

The training was more challenging than it had been on the T-41. More cadets were being removed as unsuitable for pilot training then before, saving millions in expensive jet training on the T-37 Tweet. There was an extra factor at Colorado Springs. Its airfield was 6,500 ft amsl. The engine could cope easily at that altitude but needed careful handling at a leaner mixture. A simple procedure was adopted which prescribed a standard engine setting needing no adjustments.

There was another issue. As long ago as 1949 the FAA had been seriously concerned about stall/spin accidents - 48% of fatalities had occurred in training. They decided to remove the requirement to teach recovery from spins from the Pilot’s Licence training syllabus – only prevention of stalling was to be taught. Some schools still offered spin training for those who wanted it. Most learner pilots didn’t.

The military was unaffected by this. They developed their own standard six-point spin recovery procedure. Without analysing this in detail, it’s pertinent to point out that the principal pilot action to recover from a spin is to apply opposite rudder. In the USAF’s procedure, curiously, this is point 4. Whilst the pilot is ticking off points 1 to 3, the aircraft is rapidly spinning away any height it has in reserve.

In February 1995, an instructor failed to apply rudder after a Firefly spun and he and the pupil died. In September 1996, an engine stopped during a simulated forced landing. The Firefly stalled and the occupants died. In June 1997, a pilot lost control during a turn downwind. Two more deaths. Clearly, the Firefly was at fault. The whole fleet was immediately grounded.

The military was unaffected by this. They developed their own standard six-point spin recovery procedure. Without analysing this in detail, it’s pertinent to point out that the principal pilot action to recover from a spin is to apply opposite rudder. In the USAF’s procedure, curiously, this is point 4. Whilst the pilot is ticking off points 1 to 3, the aircraft is rapidly spinning away any height it has in reserve.

In February 1995, an instructor failed to apply rudder after a Firefly spun and he and the pupil died. In September 1996, an engine stopped during a simulated forced landing. The Firefly stalled and the occupants died. In June 1997, a pilot lost control during a turn downwind. Two more deaths. Clearly, the Firefly was at fault. The whole fleet was immediately grounded.

Ten million dollars were spent ‘trying to fix the engine problems’. It was then decided that making them fit for sale would cost even more and would be ‘prohibitively expensive’. All T-3s were stored at Hondo, Texas until, nine years later, in 2006, they were finally and forcibly scrapped - a sad end to the tale.

To put all this in perspective - north of the 49th parallel, the Canadian Armed Forces used the Firefly as their basic trainer from 1992 to 2006 with no serious problem.

(The USAF’s spin training is now provided by civilian contractors. They fly the Diamond DA-20, a European plastic two-seat trainer, cleared for spinning and powered by an America Continental engine).

To put all this in perspective - north of the 49th parallel, the Canadian Armed Forces used the Firefly as their basic trainer from 1992 to 2006 with no serious problem.

(The USAF’s spin training is now provided by civilian contractors. They fly the Diamond DA-20, a European plastic two-seat trainer, cleared for spinning and powered by an America Continental engine).

Back at Kirbymoorside the variety of products coming from the factory was expanded to include hovercraft. Four of these were built for the Finnish Border Guard

Ownership of the company changed yet again. In 2007 it became part of the Triton Group, producing underwater remotely operated vehicles for the oil industry. These complex robotic manipulators were capable of working on salvage operations as deep as 4000 metres. In 2009, Triton came under some financial pressure. It was an ill wind in Florida which led to the closure of their factory there. All operations were transferred to Kirbymoorside where the factory was extended

The last change of owner came in January 2010. Marshall Aerospace recognised the value of the expertise of this little company up in rural Yorkshire and incorporated it as Marshall Slingsby Advanced Composites. It now produces a wide range of specialist components – helmets for pilots of the Typhoon and other fast jets, parts for the Hercules and Dassault Falcon, weapons carriers and torpedo tubes. Some of their components have even taken to the tracks, running on the Oslo and Madrid Metros.

UAVs also come out of the door. This little Herti was designed and built in just seven months. For this and their work on other UAVs they have been recognised with awards from BAE Systems and the RAeS. The company had built long wings for gliders in the past – up to 18 metres span. The composite wing for the Mantis programme was 24 metres long.

The spirit of Fred must be proud.

The spirit of Fred must be proud.