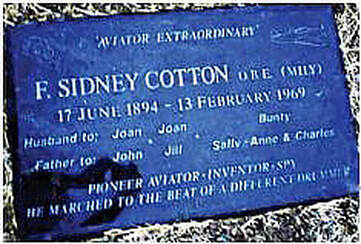

Frederick Sidney Cotton 1894 – 1969 (Dec 2018)

Sidney Cotton was raised on his father’s cattle station in Queensland. He was 20 when war broke out in Europe. Always interested in technology, he saw this as an opportunity to learn to fly and left Australia to join the RFC. On the voyage, he became involved in the navigation techniques used by the ship’s officers and changed his plan. He would join the Navy.

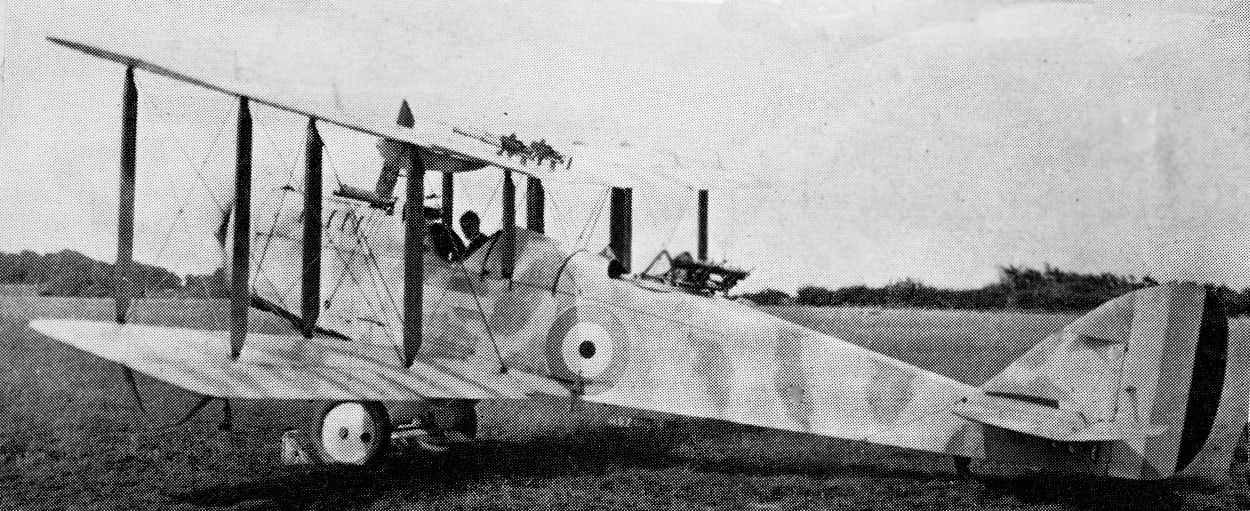

Within weeks of arriving in England, Flight Sub-Lieutenant Cotton was in a Maurice Farman Longhorn flying over an airfield near Chingford. His instructor demonstrated a circuit and landing. Under the impression that Cotton had some previous experience (he had only flown models) he promptly sent him off solo.

Sidney could have said something – he didn’t. It was a frightening experience. Hardly daring to move the controls, he gently opened the throttle and watched the Longhorn lift into the air and carry him away from the field. When he did experiment with a turn he overdid the banking and spent the next few minutes struggling to get back to level flight. Diving and climbing, twisting and turning his erratic flying attracted the attention of the other students. His first headlong attempt at landing failed and he zoomed up again. More gingerly, he trickled in for a second time and accidentally carried out a perfect landing in the marked circle.

The excited observers rushed forward and congratulated him. They thought he had been demonstrating advanced manoeuvres. Cotton learned a lesson from this episode. He had found how much he could get away with by sheer bluff.

The excited observers rushed forward and congratulated him. They thought he had been demonstrating advanced manoeuvres. Cotton learned a lesson from this episode. He had found how much he could get away with by sheer bluff.

Three days later he was posted to Andover to learn to fly the B.E. 2c. After brief instruction in navigation and using Morse code he was sent to Dover, as a qualified pilot, with just 5 hours in his log book. There he was told to take up a Breguet, an unhandy French design with a sensitive ‘all-flying’ tail. Although this made it tricky to fly its unreliable engine caused more trouble and in his first flight he force landed several times.

Nevertheless, he was immediately posted to the squadron based at Couderquerque near Dunkirk where he flew patrols over the Channel and later bombing raids on German airfields. The Breguets were even used as escort fighters.

Nevertheless, he was immediately posted to the squadron based at Couderquerque near Dunkirk where he flew patrols over the Channel and later bombing raids on German airfields. The Breguets were even used as escort fighters.

Sidney often spent time in the hangar working on his aeroplane, trying different fittings and modifications. He was there one day when there was an urgent call for the whole flight to take off. With no time to don the cumbersome fur-lined flying clothes he climbed into the aeroplane wearing just his dirty old overalls. When they all landed the other pilots complained about the cold and Sidney was surprisingly warm. He realized that his oil-soaked overalls were more effective than fur lining.

On his next leave he approached a London outfitter and had them make a flying suit with a thin fur lining, a layer of airproof silk and an outside layer of waterproof cotton. The outfitters made more and sold them to other pilots. It became known as the Sidcot suit and was so successful that thousands were made for all military fliers. Sidney made no money from this. His father had a hatred of war profiteers and Sidney hadn’t thought of making any claim for his design.

On his next leave he approached a London outfitter and had them make a flying suit with a thin fur lining, a layer of airproof silk and an outside layer of waterproof cotton. The outfitters made more and sold them to other pilots. It became known as the Sidcot suit and was so successful that thousands were made for all military fliers. Sidney made no money from this. His father had a hatred of war profiteers and Sidney hadn’t thought of making any claim for his design.

His next posting was to the newly formed No 3 (Naval) Squadron led by Raymond Collishaw. The pilots were mostly Australians and Canadians and included Charles Kingsford Smith and Chris Draper (later to be known as the Mad Major who flew under 15 Thames bridges). The squadron were equipped with the Sopwith 1½ Strutter. Volunteers were called for a major raid which was being planned on a factory near Stuttgart which made Mauser guns. Sidney put his name down.

They all moved to a field near the Swiss border. Sidney ‘disguised’ his Strutter as a fighter, fitting a gun ring on the rear cockpit with a painted shape to hint at a gunner’s presence. It didn’t do him any good. His engine began to lose power as they crossed the Vosges mountains. Sidney had to weave through the valleys. Flying low he attracted much light ack-ack fire and thought it wise to turn back. He spluttered across the lines before his engine finally stopped and he landed in a field. He had escaped from a disaster. Fifty planes had flown on the raid – only thirteen came back.

They all moved to a field near the Swiss border. Sidney ‘disguised’ his Strutter as a fighter, fitting a gun ring on the rear cockpit with a painted shape to hint at a gunner’s presence. It didn’t do him any good. His engine began to lose power as they crossed the Vosges mountains. Sidney had to weave through the valleys. Flying low he attracted much light ack-ack fire and thought it wise to turn back. He spluttered across the lines before his engine finally stopped and he landed in a field. He had escaped from a disaster. Fifty planes had flown on the raid – only thirteen came back.

On another raid he got lost in fog. Flying low, he realised he was above an airfield. He turned tightly and landed. As he taxied in he saw that the parked aeroplanes bore black crosses. He hurriedly took off again, unnoticed and headed west.

Next he moved to No 8 (Naval) squadron near Dunkirk again and was delighted to be flying the new Sopwith Pup. The Germans regularly sent a lone bomber to attack the airfield at dawn and dusk. Sidney determined to ambush him. He took off early and climbed and climbed. It took an hour to reach 18,000’. He was breathing deeply to combat the lack of oxygen when he saw the Taube far below. He turned and dived to attack – and passed out. He came to at 3000’ in the spinning Pup. His nose and ears were bleeding and he was in some pain but he recovered from the spin and landed. The squadron doctor diagnosed a burst ear drum and he was sent to England for treatment.

After a period on sick leave he was posted to Hendon where Handley Page were preparing one of the first O/400 bombers for a secret operation. It was to fly to the Greek island of Lemnos and then carry out bombing raids on Constantinople and the two German battleships docked there. It was in May 1917 when it was ready to go. At the last minute, one of the large fuel tanks was found to be leaking. It was a Saturday and the HP factory at Cricklewood was empty and locked. Sidney solved the problem in typical Cotton fashion. He had the factory guard arrested and detained. Then he broke into the factory and took a fuel tank. The guard was released, the tank fitted and the O/400 took off for its long flight to Greece. (The raid was a success, Frederick H-P complained strongly but overlooked Cotton’s offence when he was paid for the tank).

Back in Hendon, Cotton put pen to paper and submitted to the Admiralty his plan to bomb Berlin. It produced an interview with Commander Godfrey Paine, head of operations of the RNAS. Sidney explained that he would use DH-4 bombers fitted with Napier engines (the RR Eagles normally fitted used too much fuel). They would bomb Berlin then fly on to land in Russia. The plan was accepted and Sidney moved to Napier’s factory.

The Napier engines worked well enough apart from the cooling system which gave constant trouble. The water quickly reached boiling point. The Admiralty lowered its sights and aimed to carry out photographic reconnaissance of Wilhelmshaven until the cooling problem was solved. They moved Cotton’s unit to Bacton in Norfolk and told him to keep busy on anti-Zeppelin patrols.

Sidney fitted a 10 gallon water tank under his pilot’s seat with a hand pump to top up the boiled-off water. Another pilot, called Fane, was sent to join him with a second DH-4. Meanwhile, his anti-Zeppelin task was boosted by having twin Lewis guns, loaded with tracer and incendiary bullets, fitted to the upper wing to fire at an upward angle.

Since progress was being made with extending the range of the DH-4 Cotton was given the order to send Fane on a patrol to Terschelling in the Frisian Islands. Sidney protested. Fane’s DH-4 had not been fitted with the extra water tank, so he would do the patrol himself in his modified aeroplane. He was told to obey the original order. Sidney went to London to see Paine. The interview developed into a row, not about the operation but about obeying orders. Sidney said he would resign his commission. Paine told him to wait in London for a few days.

Another officer called Gilligan was appointed to take over the unit. He too was reluctant to send Fane on an operation likely to fail so, without consulting Paine, took Fane’s DH-4 himself. He reached Terschelling without trouble. Then he sighted a Zeppelin and climbed to intercept. But, of course, the engine boiled and he had to break off the attack. Halfway back to Yarmouth, the engine seized and they had to ditch the DH. A flying boat was sent to search for the crew but that, too, had engine problems and also had to ditch. Happily, the crews of both aeroplanes were found by a cruiser.

None of this was seen by Cdr Paine as any justification for Cotton’s disobedience of orders. He offered Sidney a posting to Greece for ‘another chance’. ‘No thanks’, Sidney said. ‘You were wrong and I was right. I shall go back to Australia and join the air service there’. He saluted and walked out.

He didn’t leave England immediately. He had met Joan MacLean, a Scottish actress. Although he had always been awkward with girls he impressed her enough to agree to marry him. It was 16th October 1917 - he was 23, she was 17. They travelled to Australia via America and during the trip Sidney ran out of money. He had to cable his father for help. This was rather a shock to Joan – she had the impression that he was ’rolling in money’.

From the family home, now in Tasmania, Sidney wrote to the newly formed Australian Flying Corps offering his services. Several weeks went by until the reply came. The Corps had contacted the Admiralty in London who told them ‘He is of a difficult temperament and is unsuitable for employment in a uniformed service’.

Never able to stay idle he ran his father’s apple-drying factory for a while. Next he tried to set up a farm rental company. Other ventures failed and he fell out with his father so he and Joan left for England.

Next he moved to No 8 (Naval) squadron near Dunkirk again and was delighted to be flying the new Sopwith Pup. The Germans regularly sent a lone bomber to attack the airfield at dawn and dusk. Sidney determined to ambush him. He took off early and climbed and climbed. It took an hour to reach 18,000’. He was breathing deeply to combat the lack of oxygen when he saw the Taube far below. He turned and dived to attack – and passed out. He came to at 3000’ in the spinning Pup. His nose and ears were bleeding and he was in some pain but he recovered from the spin and landed. The squadron doctor diagnosed a burst ear drum and he was sent to England for treatment.

After a period on sick leave he was posted to Hendon where Handley Page were preparing one of the first O/400 bombers for a secret operation. It was to fly to the Greek island of Lemnos and then carry out bombing raids on Constantinople and the two German battleships docked there. It was in May 1917 when it was ready to go. At the last minute, one of the large fuel tanks was found to be leaking. It was a Saturday and the HP factory at Cricklewood was empty and locked. Sidney solved the problem in typical Cotton fashion. He had the factory guard arrested and detained. Then he broke into the factory and took a fuel tank. The guard was released, the tank fitted and the O/400 took off for its long flight to Greece. (The raid was a success, Frederick H-P complained strongly but overlooked Cotton’s offence when he was paid for the tank).

Back in Hendon, Cotton put pen to paper and submitted to the Admiralty his plan to bomb Berlin. It produced an interview with Commander Godfrey Paine, head of operations of the RNAS. Sidney explained that he would use DH-4 bombers fitted with Napier engines (the RR Eagles normally fitted used too much fuel). They would bomb Berlin then fly on to land in Russia. The plan was accepted and Sidney moved to Napier’s factory.

The Napier engines worked well enough apart from the cooling system which gave constant trouble. The water quickly reached boiling point. The Admiralty lowered its sights and aimed to carry out photographic reconnaissance of Wilhelmshaven until the cooling problem was solved. They moved Cotton’s unit to Bacton in Norfolk and told him to keep busy on anti-Zeppelin patrols.

Sidney fitted a 10 gallon water tank under his pilot’s seat with a hand pump to top up the boiled-off water. Another pilot, called Fane, was sent to join him with a second DH-4. Meanwhile, his anti-Zeppelin task was boosted by having twin Lewis guns, loaded with tracer and incendiary bullets, fitted to the upper wing to fire at an upward angle.

Since progress was being made with extending the range of the DH-4 Cotton was given the order to send Fane on a patrol to Terschelling in the Frisian Islands. Sidney protested. Fane’s DH-4 had not been fitted with the extra water tank, so he would do the patrol himself in his modified aeroplane. He was told to obey the original order. Sidney went to London to see Paine. The interview developed into a row, not about the operation but about obeying orders. Sidney said he would resign his commission. Paine told him to wait in London for a few days.

Another officer called Gilligan was appointed to take over the unit. He too was reluctant to send Fane on an operation likely to fail so, without consulting Paine, took Fane’s DH-4 himself. He reached Terschelling without trouble. Then he sighted a Zeppelin and climbed to intercept. But, of course, the engine boiled and he had to break off the attack. Halfway back to Yarmouth, the engine seized and they had to ditch the DH. A flying boat was sent to search for the crew but that, too, had engine problems and also had to ditch. Happily, the crews of both aeroplanes were found by a cruiser.

None of this was seen by Cdr Paine as any justification for Cotton’s disobedience of orders. He offered Sidney a posting to Greece for ‘another chance’. ‘No thanks’, Sidney said. ‘You were wrong and I was right. I shall go back to Australia and join the air service there’. He saluted and walked out.

He didn’t leave England immediately. He had met Joan MacLean, a Scottish actress. Although he had always been awkward with girls he impressed her enough to agree to marry him. It was 16th October 1917 - he was 23, she was 17. They travelled to Australia via America and during the trip Sidney ran out of money. He had to cable his father for help. This was rather a shock to Joan – she had the impression that he was ’rolling in money’.

From the family home, now in Tasmania, Sidney wrote to the newly formed Australian Flying Corps offering his services. Several weeks went by until the reply came. The Corps had contacted the Admiralty in London who told them ‘He is of a difficult temperament and is unsuitable for employment in a uniformed service’.

Never able to stay idle he ran his father’s apple-drying factory for a while. Next he tried to set up a farm rental company. Other ventures failed and he fell out with his father so he and Joan left for England.

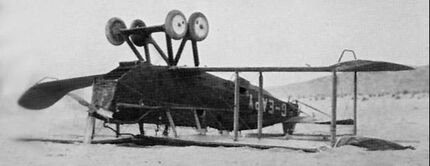

Using his previous contacts he managed to get a job with Napiers, nursing the idea that it could lead to attempting a flight from England to Australia. The Aircraft Manufacturing Company, run by Sefton Brancker – another wartime contact - had prepared the one and only DH-14A, powered by a Napier engine, and with the potential of extending its range for a trans-Atlantic flight.

This Atlantic plan was scotched by Alcock and Brown and Sydney’s plan for the Australia flight by Ross and Keith Smith, leaving just the first flight to South Africa as a record still in waiting. Sidney persuaded Brancker to let him try and also to give him the DH 14 if he succeeded. Napier helped by lending him an engineer, named Townsend.

In the midst of these preparations, Sidney came home one night and found a note from Joan. She had gone to New York on the promise of an acting job. He was left with his 12 month old son whom he parked temporarily with Joan’s parents before sending him later to be with his mother. Sidney and Joan were to meet briefly just once more before divorcing in 1925.

In January 1920 the DH-14 was ready and Sidney and Townsend took off from Hendon. Minutes later, the oil pressure valve blew out and the oil-soaked aviators slithered into Handley Page’s aerodrome at Cricklewood. After a quick change of valve – and clothes - they set off again. This time they got as far as Paris before more engine trouble forced them down again. Napier sent their chief engineer to fix the engine properly.

In the midst of these preparations, Sidney came home one night and found a note from Joan. She had gone to New York on the promise of an acting job. He was left with his 12 month old son whom he parked temporarily with Joan’s parents before sending him later to be with his mother. Sidney and Joan were to meet briefly just once more before divorcing in 1925.

In January 1920 the DH-14 was ready and Sidney and Townsend took off from Hendon. Minutes later, the oil pressure valve blew out and the oil-soaked aviators slithered into Handley Page’s aerodrome at Cricklewood. After a quick change of valve – and clothes - they set off again. This time they got as far as Paris before more engine trouble forced them down again. Napier sent their chief engineer to fix the engine properly.

They reached Rome. Pre-flight checks next morning revealed a loose propeller. The bearing behind the prop had been starved of oil and had broken down. It took a day and a half to get a new one fitted and Sidney thought they could reach Catania in Sicily before nightfall. The headwind they met proved otherwise. With no hope of reaching Sicily Sidney resorted to a convenient beach near Naples.

A tyre burst and the aeroplane turned over onto its back. The DH-14 came home in a packing case. Brancker sold Sidney the wreck for £500 – then repaired it for nothing.

Before the repairs were finished, Sidney entered it in the Aerial Derby - two 100 mile circuits of Greater London. He arranged for the repairers to streamline any projections and give the fabric a hard shiny dope finish. He was confident this would increase his cruising speed and, more mportantly, fool the handicappers.

In the race, all was going well. None of the faster planes behind had caught up with him and he was nearing the end of the first lap. He had just overtaken Bert Hinckler in his Baby Avro when the engine suddenly burst into flames. He switched off the petrol and sideslipped until the flames burned out. At only 800 feet he had to find a landing field quickly. Turning tightly he almost spun and found himself too low to clear a looming line of trees. He passed between two trees which tore off the wings and he and the fuselage finished upside down in a barley field. The DH was a write off. Cannily, he had taken out insurance before the race and although he now had no aeroplane he was suddenly £5000 richer.

A tyre burst and the aeroplane turned over onto its back. The DH-14 came home in a packing case. Brancker sold Sidney the wreck for £500 – then repaired it for nothing.

Before the repairs were finished, Sidney entered it in the Aerial Derby - two 100 mile circuits of Greater London. He arranged for the repairers to streamline any projections and give the fabric a hard shiny dope finish. He was confident this would increase his cruising speed and, more mportantly, fool the handicappers.

In the race, all was going well. None of the faster planes behind had caught up with him and he was nearing the end of the first lap. He had just overtaken Bert Hinckler in his Baby Avro when the engine suddenly burst into flames. He switched off the petrol and sideslipped until the flames burned out. At only 800 feet he had to find a landing field quickly. Turning tightly he almost spun and found himself too low to clear a looming line of trees. He passed between two trees which tore off the wings and he and the fuselage finished upside down in a barley field. The DH was a write off. Cannily, he had taken out insurance before the race and although he now had no aeroplane he was suddenly £5000 richer.

The advert in The Aeroplane said ‘Pilots wanted. Plenty of risk - good pay’. Sidney couldn’t resist. He met Major Clayton-Kennedy, a Canadian who had won a contract for seal-spotting in Newfoundland. He had two DH-9s which he was going to use. Sidney thought them unsuitable for long-range work in the Newfoundland winter and arranged to bring his own aeroplane, a Westland Limousine which he intended to buy with his insurance money – it would use the Napier Lion which he had salvaged from the DH-14 crash. Although the pilot was in an open cockpit the passengers, up to six of them, sat in an enclosed cabin.

With an old friend as second pilot and two mechanics Sidney set sail from Liverpool in November 1920. On arrival in St John’s, Newfoundland, he met a pilot who, with no idea who he was told him ‘There’s only one flying suit any good out here and that’s the Sidcot’.

With an old friend as second pilot and two mechanics Sidney set sail from Liverpool in November 1920. On arrival in St John’s, Newfoundland, he met a pilot who, with no idea who he was told him ‘There’s only one flying suit any good out here and that’s the Sidcot’.

Clayton-Kennedy’s contract was already in trouble and the sealing-ship captains threatened to pull out. Sidney took over. Provided he was given all the aircraft and equipment he would re-negotiate the terms of the contract. He found a suitable place for an airfield at Botwood and began building a hangar. It needed ice-picks to dig into the frozen ground. As an extra money earner he arranged with the Postal Service to deliver mail to villages by air drop from the DH 9s and so established the first air mail in Newfoundland.

The Napier Lion in the Westland failed yet again and Sydney brought it back to England to have it re-built. Whist in London he found a wealthy investor who put up £100,000 to keep the business going. He was able to buy more planes and equipment and established another first (in a ski-equipped DH-9) – carrying airmail between Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. He signed a contract with a map-making company and began taking photographs - with a hand-held camera clamping the stick between his knees. He was working hard but none of his efforts was making much money and he had escaped from death more than once in the harsh ice-bound winters. In the summer of 1923, he sold all his assets and left Newfoundland with $25,000.

The Napier Lion in the Westland failed yet again and Sydney brought it back to England to have it re-built. Whist in London he found a wealthy investor who put up £100,000 to keep the business going. He was able to buy more planes and equipment and established another first (in a ski-equipped DH-9) – carrying airmail between Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. He signed a contract with a map-making company and began taking photographs - with a hand-held camera clamping the stick between his knees. He was working hard but none of his efforts was making much money and he had escaped from death more than once in the harsh ice-bound winters. In the summer of 1923, he sold all his assets and left Newfoundland with $25,000.

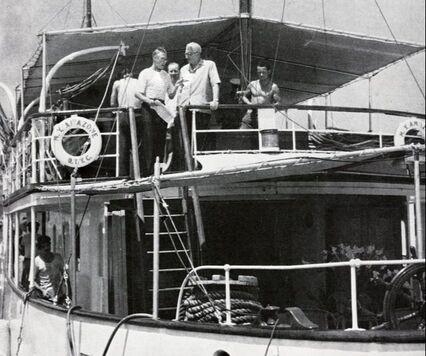

Actually, he had more than just the money. He came home with someone who was to become his wife.

Near one of the airstrips in Newfoundland used by Cotton’s aeroplanes was an isolated farmhouse. The Henry family who lived there became friendly with the pilots, particularly with Sidney and also Thomas Breakell, an English ex-RFC pilot who had come out to Newfoundland to fly one of the Westland Limousines. The Henrys had two young daughters, Joan and Kathleen, who had been educated by their mother. Joan was 15 and Mrs Henry wanted her to have some formal education in England and Sidney generously contributed £2000 to offset the costs of travel and schooling.

Sidney visited the family regularly whenever he travelled to England. It might have been a combination of hero-worship, hatred of the formal school on the Costa Geriatrica of Bournemouth and gratitude but when she was 18, Joan married the 31 year old Sydney. (The marriage was to last until 1944). Thomas Breakell also married a Henry girl, Kathleen, and went on to a long career in airlines.

Mrs Henry, Kathleen, Thomas Breakell, unknown, Joan, Sidney Cotton.

(Pic. Louise Downer, Née Breakell, granddaughter of Thomas).

Mrs Henry, Kathleen, Thomas Breakell, unknown, Joan, Sidney Cotton.

(Pic. Louise Downer, Née Breakell, granddaughter of Thomas).

For the next few years Sidney travelled in America trying out any venture that would make money. None of them made enough. The most promising appeared when he was pursuing his interest in aerial photography. A Frenchman called Louis Dufay had invented a new method of producing colour prints and tried to sell it to film manufacturers, including Ilford. They all turned him down. A film technician who had retired from Ilford had experimented with Dufay’s system and showed Sidney some of his prints. The quality was good and its chief feature was that it could be developed by the photographer. Its competitor, Kodachrome, which was coming onto the market, had to be returned to Kodak for developing. Sidney tracked down Dufay’s financial backer and made a deal.

Thus it came about that a company called Dufaycolor was registered in 1933 with Sidney holding 52% of the shares. The quality of the prints depended on the number of tiny dots of primary colours that could be engraved on the film emulsion using stainless steel rollers. Sidney found that the finest rollers were being produced by a company in Germany. He got them to make some special rollers that produced nearly twice as many dots that any they had previously made. Then he went back to Ilford. They had the facilities to mass produce and market Dufaycolor films. The advantages of doing this were obvious and they readily agreed to set up a separate company in which Sidney, of course, had a minor share.

He had already recruited a small group of film technicians who were looking at ways to improve the process. When Ilford explained their slow progress was caused by a lack of trained technicians he told them he already had them. When they said they were working on suitable developing tanks for amateur use he said ‘You mean, like these’. He also offered properly designed and printed cartons to contain the films and tanks. They had never worked with anyone like Sidney before and it caused serious boardroom rows and almost the cancellation of the contract. However commonsense prevailed, pride was swallowed and production of 35mm and 16mm Dufaycolor film commenced.

80% of colour film usage was in America, to where Sidney now turned his attention. First, he set up a company, Dufaycolor Incorporated. He arranged exhibitions of colour prints and stands at trade shows and crossed the Atlantic frequently always taking his special bodied drop-head Rolls Royce coupé to add impact to his sales pitch. Sales of Dufaycolor rose dramatically, particularly when the National Geographic magazine specified it as their preferred colour film. Other film manufacturers wanted to get involved and Sidney signed agreements in several countries. In one year he made the trans-Atlantic voyage twenty times. But his urgent method of doing business made him few friends and he was losing control of several of his companies who seldom saw him.

Then in 1936 he got a demand for £13000 from the Official Receiver for unpaid taxes for a firm which had gone into bankruptcy in 1927. Sidney had been the major shareholder and unaware that the money had been unpaid because of a genuine mistake. Having a Receiving Order meant he could not hold any directorships and he had to resign from all his companies. When it was all resolved, the Receiver settled for £5000. Sidney, however, was unable to regain his place on the boards of many of his companies.

To compound his misfortune, he and his wife separated. With all of Sidney’s travelling, Joan had been living a very different life and the separation merely formalised the status quo. They finally divorced in 1944.

One morning in September 1938 Sidney received a phone call. A man called Fred Winterbotham asked to come and see him. Like Cotton, Fred had been a pilot in WWI but his subsequent career had been very different. He had joined MI6 and by then was Chief of Air Intelligence. He asked Sidney if he would be interested in doing some aerial photography. At the time, Sidney was negotiating with Agfa in Germany who wanted a licence to put Dufaycolor on their film base. Winterbotham offered the use of an aircraft to fly to and from Germany, secretly taking photographs on the way. He would be paid a generous allowance to cover all his expenses. It was exactly the kind of deal that Sidney liked.

Thus it came about that a company called Dufaycolor was registered in 1933 with Sidney holding 52% of the shares. The quality of the prints depended on the number of tiny dots of primary colours that could be engraved on the film emulsion using stainless steel rollers. Sidney found that the finest rollers were being produced by a company in Germany. He got them to make some special rollers that produced nearly twice as many dots that any they had previously made. Then he went back to Ilford. They had the facilities to mass produce and market Dufaycolor films. The advantages of doing this were obvious and they readily agreed to set up a separate company in which Sidney, of course, had a minor share.

He had already recruited a small group of film technicians who were looking at ways to improve the process. When Ilford explained their slow progress was caused by a lack of trained technicians he told them he already had them. When they said they were working on suitable developing tanks for amateur use he said ‘You mean, like these’. He also offered properly designed and printed cartons to contain the films and tanks. They had never worked with anyone like Sidney before and it caused serious boardroom rows and almost the cancellation of the contract. However commonsense prevailed, pride was swallowed and production of 35mm and 16mm Dufaycolor film commenced.

80% of colour film usage was in America, to where Sidney now turned his attention. First, he set up a company, Dufaycolor Incorporated. He arranged exhibitions of colour prints and stands at trade shows and crossed the Atlantic frequently always taking his special bodied drop-head Rolls Royce coupé to add impact to his sales pitch. Sales of Dufaycolor rose dramatically, particularly when the National Geographic magazine specified it as their preferred colour film. Other film manufacturers wanted to get involved and Sidney signed agreements in several countries. In one year he made the trans-Atlantic voyage twenty times. But his urgent method of doing business made him few friends and he was losing control of several of his companies who seldom saw him.

Then in 1936 he got a demand for £13000 from the Official Receiver for unpaid taxes for a firm which had gone into bankruptcy in 1927. Sidney had been the major shareholder and unaware that the money had been unpaid because of a genuine mistake. Having a Receiving Order meant he could not hold any directorships and he had to resign from all his companies. When it was all resolved, the Receiver settled for £5000. Sidney, however, was unable to regain his place on the boards of many of his companies.

To compound his misfortune, he and his wife separated. With all of Sidney’s travelling, Joan had been living a very different life and the separation merely formalised the status quo. They finally divorced in 1944.

One morning in September 1938 Sidney received a phone call. A man called Fred Winterbotham asked to come and see him. Like Cotton, Fred had been a pilot in WWI but his subsequent career had been very different. He had joined MI6 and by then was Chief of Air Intelligence. He asked Sidney if he would be interested in doing some aerial photography. At the time, Sidney was negotiating with Agfa in Germany who wanted a licence to put Dufaycolor on their film base. Winterbotham offered the use of an aircraft to fly to and from Germany, secretly taking photographs on the way. He would be paid a generous allowance to cover all his expenses. It was exactly the kind of deal that Sidney liked.

Within weeks Sidney was flying a Lockheed 12A. Powered by twin P & W Wasp engines it had a range of over 1000 miles. It was registered to Imperial Airways. Sitting alongside was Bob Niven, a quiet Canadian appointed by Winterbotham. In the cabin behind was a girl called Pat Martin, Sidney’s mistress.

Sidney had met Pat Martin in 1933 when she was 18. She was an accomplished horsewoman even though she had been born with club feet and wore metal braces on her legs. The 39 year old Cotton whisked her into a world of high living, driving between his county house and London flat in his RR coupé. He arranged for the operation to straighten her club feet and gave her an electric wheelchair during her convalescence. Now he told her enough about what he was doing to make her an effective part of his cover story.

The Lockheed was flying to French Somalia at the Southern end of the Red Sea. Sidney had a number of cover stories but the real purpose of the flight was to test the long range tanks and the three F 24 cameras fitted in the floor of the cabin. The Lockheed was painted overall in a new colour named Camotint, later called duck egg blue and intended to merge the plane with a blue sky. The first refuelling stop was in Malta. The next day a sight-seeing flight over Sicily happened to pass over a number of Italian military sites. Then it was on to Egypt, via the Dodecanese islands of Leros and Rhodes, being fortified by the Italians.

Around the Red Sea, the RAF were forbidden to fly over Italian occupied Eritrea and Abyssinia but this ban was ignored by the high flying Lockheed. The route home was just as productive in photographic targets since it followed the coast of Libya to Benghazi. Overall, the flight was a great success in the photographs it produced and also in the highlighting of areas of problems to be overcome.

The Lockheed was flying to French Somalia at the Southern end of the Red Sea. Sidney had a number of cover stories but the real purpose of the flight was to test the long range tanks and the three F 24 cameras fitted in the floor of the cabin. The Lockheed was painted overall in a new colour named Camotint, later called duck egg blue and intended to merge the plane with a blue sky. The first refuelling stop was in Malta. The next day a sight-seeing flight over Sicily happened to pass over a number of Italian military sites. Then it was on to Egypt, via the Dodecanese islands of Leros and Rhodes, being fortified by the Italians.

Around the Red Sea, the RAF were forbidden to fly over Italian occupied Eritrea and Abyssinia but this ban was ignored by the high flying Lockheed. The route home was just as productive in photographic targets since it followed the coast of Libya to Benghazi. Overall, the flight was a great success in the photographs it produced and also in the highlighting of areas of problems to be overcome.

In preparation for the flights over Germany three of their latest Leica Reporter cameras were bought. Sidney had them fitted in the belly of the plane one pointing vertically downwards, the others angled outward. They were concealed by a sliding portion of the fuselage skin which could be opened by a windscreen wiper motor. That accidentally solved the condensation problem. When the panel opened warm air was sucked out of the cabin past the lenses which stayed clear and not affected by condensation which would otherwise cloud the lenses above 8,000 feet.

To give the pilot a better view downwards Sidney had a Perspex teardrop window made. He took out a patent on this and licensed it to Triplex. In the end, over 10,000 were produced and Sidney again adopted his anti-war-profiteer stance and made no claim. In tests, he positioned the Lockheed correctly over the target and the Leicas worked perfectly up to 20,000 feet.

To give the pilot a better view downwards Sidney had a Perspex teardrop window made. He took out a patent on this and licensed it to Triplex. In the end, over 10,000 were produced and Sidney again adopted his anti-war-profiteer stance and made no claim. In tests, he positioned the Lockheed correctly over the target and the Leicas worked perfectly up to 20,000 feet.

For more serious work, two of the RAF’s newest cameras were borrowed. Winterbotham himself helped to file off all the numbers which could identify them as RAF cameras. The Lockheed was, after all, a civilian plane. These cameras were concealed by having the fuel tank built around them.

Sidney then put on his Dufay hat and went to visit Herr Schöne, Agfa’s representative. He travelled by air - several times and at first with no cameras fitted. Sidney was sure that the aeroplane had been thoroughly searched more than once. The Germans became familiar with the pale blue Lockheed. The Commandant of Tempelhof Airport, Rudolf Bottger, invited Sidney to fly to an air rally to be held at Frankfurt. Sidney took an Australian reporter and C G Grey, editor of ‘The Aeroplane’. He also fitted two Leica cameras. They got a warm welcome at the rally. Bottger said he’d love a flight in the Lockheed. Sidney mentioned that his favourite aunt had always said the Rhine at Mannheim was particularly nice. Could we fly there? Bottger went off to get official clearance.

On the flight, he sat beside Sidney enjoying the view from 2000 feet. He could not, of course, see Sidney pressing the button which was firing the Leicas as they flew over several military installations. The following day, there were so many aircraft leaving the rally that Sidney’s weaving flight above the Siegfried line was unnoticed. The visit to the rally had been a great success.

Herr Schöne was proud of his friendship with Goering. He had shown him some of the marvellous Dufay pictures and Goering said he’d like to meet this Australian. So Sidney was invited to Karinhall, Goering’s country estate, together with a Dufay film crew to take a series of photographs of the house.

He flew from Heston on 17th August 1939 taking a slightly roundabout route to photograph some airfields north of Berlin. Schöne met him. ‘Security wants to know why you were flying so far north’ he said. ‘Oh, I always fly a great circle course’, said Sidney. ‘Ah yes. Like Lindbergh’ smiled Schöne.

Sidney was impressed by Goering’s luxurious estate and delighted by the friendly reception he was given. Whilst the building was extensively recorded on film by the Dufay team a plan formed in Sidney’s mind. If only he could get Goering to come to Britain for direct talks then the threatened war might be avoided. He contacted Lord Halifax, the British Foreign Secretary and fervent peacemaker who agreed with the plan. Via Schöne Sidney offered to fly Goering himself in the Lockheed. To his utter surprise, his offer was accepted.

Sidney’s plan was to pick up Goering from a small airfield near Munich and fly him to White Waltham. He even proposed that he would use his own car, rather than an official limousine, to deliver Goering to Chequers. Winterbotham was told of the scheme and did not like it at all. He thought it was ‘crackpot’. He couldn’t stop it – it had been approved by the Prime Minister, no less, but he worked out a code to send messages to Sidney when he went back to Berlin.

Sidney took his Canadian co-pilot, Bob Niven, when he flew back to Germany. As Australian and Canadian nationals there was a thin detachment from Anglo-German relations which might possibly have been useful if things went wrong. They took out the Lockheed’s fixed cameras but kept a couple of Leicas in their hiding place in the cabin. The trigger for the operation was a hand-written letter Sidney had brought from Lord Halifax. They waited in a Berlin hotel, expecting to make the flight with Goering on 24th August.

On the evening of the 23th, Sidney received a telegram from Mary (Winterbotham) saying his mother was very ill and asking for him. Also he was visited by an official from the German Foreign Office telling him he had to leave Germany. He wasn’t told the reason but it was because Hitler had signed a non-aggression pact with Stalin which effectively cleared the way for an invasion of Poland. Later that evening Sidney learned that his mother was sinking fast and urgently need to see her son.

At dawn next morning, the Lockheed taxied towards the runway ready to take off. A steady red light from the control tower halted them. They stopped, with the engines ticking over. After a while, a car arrived with a very agitated airfield commandant. ‘All flying is banned. We are trying to get special permission for you to go.’ It took another long wait and a phone call to Goering for clearance to be given. It came with a detailed route across north Germany to the Dutch border. ‘If you deviate from this, you will be shot down’.

They stuck to the route, always looking for possible subjects for the Leicas. Flying at precisely 300 metres there was little of interest to be seen in the 250 miles to the Dutch border. Then they flew clear of the cloud and Niven looked over his shoulder. Glistening in the sunshine he saw in the distance a line of warships in the Wilhelmshaven roads. The quality lens of the Leica transferred the image to film.

Two days later, Cotton and Niven planned a flight to Copenhagen ‘on business’. Sidney’s mistress, Pat Martin, insisted on coming with them. It helped their cover and she had proved to be useful on their ‘holiday’ to East Africa. They flew as close as they could to the German East Frisian Islands. Niven operated the F.24 cameras and Pat clicked away with the hand held Leica from the co-pilot’s seat. More useful pictures were taken as they flew directly over the German airfield on Sylt.

Sidney was skating on very thin ice. His Goering plan had infuriated MI6 and the Foreign Office. Both wanted to get rid of him. But his photographs had made such an impact in high places that his work was in demand, particularly by the Royal Navy. Unknown to Cotton, the Navy was planning to take over his organization from MI6 because he was supplying excellent photographs whilst the RAF Photographic Unit seemed unable to get any. Sidney was asked to go and talk to AVM Richard Peck.

Peck was surprised to learn that Sidney had no special equipment and yet was achieving such good results. He admitted that the RAF had been asked by the Navy for up to date photographs of the Dutch ports of Flushing and Ijmuiden by they had lost some Blenheims and failed to get anything useful. Would Cotton come back to another meeting tomorrow with RAF pilots and technicians?

Back in his office, Sydney looked out at the weather. It was a perfect day. Why not? He rang Heston and told Bob Niven to get the Lockheed ready. ‘White Flight taking off’. It was the agreed message to inform RAF Air Traffic Control whenever they were airborne. They flew over the targets at 11,000 feet and landed at Farnborough where the processing technicians had been warned to do a rush job and print 12” x12” enlargements. They were mounted in a special album.

The meeting the following day was crowded. Unexpectedly, Air Marshal Sir Richard Peirse, the Vice-Chief of Air Staff, had decided to attend the meeting. Sidney let the discussion ramble on waiting for the right moment to produce his album. ‘Is this the sort of thing you want?’ Everyone was impressed. AVM Peck assumed the pictures had been taken in peacetime. ‘You wouldn’t expect this superb quality in wartime. When were they taken?’ Sidney produced his bombshell – ‘3.15 yesterday afternoon’. The meeting erupted. ‘You can’t do this . . . flouting authority. . . should be arrested. . . ‘. It went on and on until Sidney could stand it no longer and left, slammimg the door behind him.

The next day he was called to the office of the Chief of Air Staff, Air Chief Marshal Sir Cyril Newall. Although he deplored Sydney’s methods the CAS suggested that Cotton should take over the RAF’s Photographic unit. Sidney refused. He realised that he could not work restrained by service red tape. He offered to run a special unit in his own way and based at a civil airfield. If that was the way to get the results he wanted Newall agreed. Sidney was made a Wing Commander and would report directly to AVM Peck. He was given the services of a squadron leader from the Establishments section to steer him through the selection and appointment of personnel. Bob Niven became a flight lieutenant and Shorty Longbottom, a pilot he had met on his trip to East Africa, was his first in-service posting. Soon, the little unit of 5 officers and 17 other ranks was setting up shop in an Airwork hangar and the clubhouse of the pre-war flying club at Heston.

Sidney was introduced to the RAF’s director of Research and Development, a helpful Air Commodore Tedder. Sidney wanted two Spitfires but all were earmarked to build up Fighter Command’s squadrons. The RAF’s PR aircraft was the Blenheim and Tedder advised him to start with two of those and also to liaise closely with Farnborough if he intended to make any modifications. He did. He had all unnecessary equipment, including the guns, removed and all paint stripped off. Any holes were filled with plaster of paris, any projections smoothed and streamlined, spinners fitted to the propellers and a blister window for the pilot. Finally, they were painted in semi-gloss Camotint. It resulted in a speed increase of 18 mph but it didn’t make the Blenheim suitable as a PR aircraft. However, all the work would prove to have a benefit.

Sidney then put on his Dufay hat and went to visit Herr Schöne, Agfa’s representative. He travelled by air - several times and at first with no cameras fitted. Sidney was sure that the aeroplane had been thoroughly searched more than once. The Germans became familiar with the pale blue Lockheed. The Commandant of Tempelhof Airport, Rudolf Bottger, invited Sidney to fly to an air rally to be held at Frankfurt. Sidney took an Australian reporter and C G Grey, editor of ‘The Aeroplane’. He also fitted two Leica cameras. They got a warm welcome at the rally. Bottger said he’d love a flight in the Lockheed. Sidney mentioned that his favourite aunt had always said the Rhine at Mannheim was particularly nice. Could we fly there? Bottger went off to get official clearance.

On the flight, he sat beside Sidney enjoying the view from 2000 feet. He could not, of course, see Sidney pressing the button which was firing the Leicas as they flew over several military installations. The following day, there were so many aircraft leaving the rally that Sidney’s weaving flight above the Siegfried line was unnoticed. The visit to the rally had been a great success.

Herr Schöne was proud of his friendship with Goering. He had shown him some of the marvellous Dufay pictures and Goering said he’d like to meet this Australian. So Sidney was invited to Karinhall, Goering’s country estate, together with a Dufay film crew to take a series of photographs of the house.

He flew from Heston on 17th August 1939 taking a slightly roundabout route to photograph some airfields north of Berlin. Schöne met him. ‘Security wants to know why you were flying so far north’ he said. ‘Oh, I always fly a great circle course’, said Sidney. ‘Ah yes. Like Lindbergh’ smiled Schöne.

Sidney was impressed by Goering’s luxurious estate and delighted by the friendly reception he was given. Whilst the building was extensively recorded on film by the Dufay team a plan formed in Sidney’s mind. If only he could get Goering to come to Britain for direct talks then the threatened war might be avoided. He contacted Lord Halifax, the British Foreign Secretary and fervent peacemaker who agreed with the plan. Via Schöne Sidney offered to fly Goering himself in the Lockheed. To his utter surprise, his offer was accepted.

Sidney’s plan was to pick up Goering from a small airfield near Munich and fly him to White Waltham. He even proposed that he would use his own car, rather than an official limousine, to deliver Goering to Chequers. Winterbotham was told of the scheme and did not like it at all. He thought it was ‘crackpot’. He couldn’t stop it – it had been approved by the Prime Minister, no less, but he worked out a code to send messages to Sidney when he went back to Berlin.

Sidney took his Canadian co-pilot, Bob Niven, when he flew back to Germany. As Australian and Canadian nationals there was a thin detachment from Anglo-German relations which might possibly have been useful if things went wrong. They took out the Lockheed’s fixed cameras but kept a couple of Leicas in their hiding place in the cabin. The trigger for the operation was a hand-written letter Sidney had brought from Lord Halifax. They waited in a Berlin hotel, expecting to make the flight with Goering on 24th August.

On the evening of the 23th, Sidney received a telegram from Mary (Winterbotham) saying his mother was very ill and asking for him. Also he was visited by an official from the German Foreign Office telling him he had to leave Germany. He wasn’t told the reason but it was because Hitler had signed a non-aggression pact with Stalin which effectively cleared the way for an invasion of Poland. Later that evening Sidney learned that his mother was sinking fast and urgently need to see her son.

At dawn next morning, the Lockheed taxied towards the runway ready to take off. A steady red light from the control tower halted them. They stopped, with the engines ticking over. After a while, a car arrived with a very agitated airfield commandant. ‘All flying is banned. We are trying to get special permission for you to go.’ It took another long wait and a phone call to Goering for clearance to be given. It came with a detailed route across north Germany to the Dutch border. ‘If you deviate from this, you will be shot down’.

They stuck to the route, always looking for possible subjects for the Leicas. Flying at precisely 300 metres there was little of interest to be seen in the 250 miles to the Dutch border. Then they flew clear of the cloud and Niven looked over his shoulder. Glistening in the sunshine he saw in the distance a line of warships in the Wilhelmshaven roads. The quality lens of the Leica transferred the image to film.

Two days later, Cotton and Niven planned a flight to Copenhagen ‘on business’. Sidney’s mistress, Pat Martin, insisted on coming with them. It helped their cover and she had proved to be useful on their ‘holiday’ to East Africa. They flew as close as they could to the German East Frisian Islands. Niven operated the F.24 cameras and Pat clicked away with the hand held Leica from the co-pilot’s seat. More useful pictures were taken as they flew directly over the German airfield on Sylt.

Sidney was skating on very thin ice. His Goering plan had infuriated MI6 and the Foreign Office. Both wanted to get rid of him. But his photographs had made such an impact in high places that his work was in demand, particularly by the Royal Navy. Unknown to Cotton, the Navy was planning to take over his organization from MI6 because he was supplying excellent photographs whilst the RAF Photographic Unit seemed unable to get any. Sidney was asked to go and talk to AVM Richard Peck.

Peck was surprised to learn that Sidney had no special equipment and yet was achieving such good results. He admitted that the RAF had been asked by the Navy for up to date photographs of the Dutch ports of Flushing and Ijmuiden by they had lost some Blenheims and failed to get anything useful. Would Cotton come back to another meeting tomorrow with RAF pilots and technicians?

Back in his office, Sydney looked out at the weather. It was a perfect day. Why not? He rang Heston and told Bob Niven to get the Lockheed ready. ‘White Flight taking off’. It was the agreed message to inform RAF Air Traffic Control whenever they were airborne. They flew over the targets at 11,000 feet and landed at Farnborough where the processing technicians had been warned to do a rush job and print 12” x12” enlargements. They were mounted in a special album.

The meeting the following day was crowded. Unexpectedly, Air Marshal Sir Richard Peirse, the Vice-Chief of Air Staff, had decided to attend the meeting. Sidney let the discussion ramble on waiting for the right moment to produce his album. ‘Is this the sort of thing you want?’ Everyone was impressed. AVM Peck assumed the pictures had been taken in peacetime. ‘You wouldn’t expect this superb quality in wartime. When were they taken?’ Sidney produced his bombshell – ‘3.15 yesterday afternoon’. The meeting erupted. ‘You can’t do this . . . flouting authority. . . should be arrested. . . ‘. It went on and on until Sidney could stand it no longer and left, slammimg the door behind him.

The next day he was called to the office of the Chief of Air Staff, Air Chief Marshal Sir Cyril Newall. Although he deplored Sydney’s methods the CAS suggested that Cotton should take over the RAF’s Photographic unit. Sidney refused. He realised that he could not work restrained by service red tape. He offered to run a special unit in his own way and based at a civil airfield. If that was the way to get the results he wanted Newall agreed. Sidney was made a Wing Commander and would report directly to AVM Peck. He was given the services of a squadron leader from the Establishments section to steer him through the selection and appointment of personnel. Bob Niven became a flight lieutenant and Shorty Longbottom, a pilot he had met on his trip to East Africa, was his first in-service posting. Soon, the little unit of 5 officers and 17 other ranks was setting up shop in an Airwork hangar and the clubhouse of the pre-war flying club at Heston.

Sidney was introduced to the RAF’s director of Research and Development, a helpful Air Commodore Tedder. Sidney wanted two Spitfires but all were earmarked to build up Fighter Command’s squadrons. The RAF’s PR aircraft was the Blenheim and Tedder advised him to start with two of those and also to liaise closely with Farnborough if he intended to make any modifications. He did. He had all unnecessary equipment, including the guns, removed and all paint stripped off. Any holes were filled with plaster of paris, any projections smoothed and streamlined, spinners fitted to the propellers and a blister window for the pilot. Finally, they were painted in semi-gloss Camotint. It resulted in a speed increase of 18 mph but it didn’t make the Blenheim suitable as a PR aircraft. However, all the work would prove to have a benefit.

The Lockheed was still available for any request for photographs. It came from Sidney’s most appreciative customer. One day in September, he had a visitor in his flat, a naval intelligence officer, one Lt Cdr Ian Fleming. (They got on very well together and there has since been speculation that some of Sidney’s activities might have provided the inspiration for James Bond stories). The navy was concerned that the Germans could be setting up secret refuelling stations in neutral Ireland for their Atlantic U-boat operations. So Sidney and Bob Niven carried out several flights photographing the many bays and inlets on the Irish west coast.

Fighter Command were fitting out some Blenheims as long range fighters and ACM Sir Hugh Dowding heard that Cotton had increased the speed of a Blenheim. He called in at Heston to see it and had one of his pilots fly it. When he tried to get the fighter Blenheims which were being delivered to be ‘’Cottonized’ by the manufacturers he was told that it couldn’t be done. Sidney’s engineers were not too busy and he suggested that they could do the work. They modified eight Blenheims in a week and Dowding was delighted. ‘If there is anything I can do for you, let me know’, he said. Sidney took the plunge – ‘Could you lend me a couple of Spitfires?’ The next morning, two Spitfires landed at Heston. (Sidney was on the mat when Peck found out about this. Even Dowding came in for some criticism).

The Spitfires were duly ‘Cottonized’ and the maximum speed went up from 360 to 396 mph. A 29 gallon tank could go under the pilot’s seat and small tanks were squeezed into the leading edges. The range of the PR Spitfire was now 1250 miles. Fitting the camera in the fuselage behind the pilot was more difficult but a solution was found. The prototype Spitfire had a fixed pitch wooden two blade propeller weighing 88 lbs. The metal three blade variable pitch prop which replaced it in later production Spitfires weighed 375 lbs. To balance that, 32 lbs of lead weights were packed in the fuselage behind the tail. These were removed and the weight of the camera restored the balance. A heating duct was fitted reaching the camera’s housing which would prevent condensation. By October 1939 the unit was fully equipped for operations.

Sidney was asked to go to see Air Marshal Arthur (‘Ugly’) Barratt, the C-in-C of the RAF contingent in France. Barratt had only Blenheims and Battles for PR work, flying usually between 5,000 and 10,000 feet but they were frequently intercepted and had been suffering heavy losses. Sidney was confident that his Spitfire was unlikely to be detected at 30,000 ft and that was the case when Shorty Longbottom flew the first high level PR sortie along the whole Siegfried line. The film was rushed back to Heston for processing and revealed another problem.

Fighter Command were fitting out some Blenheims as long range fighters and ACM Sir Hugh Dowding heard that Cotton had increased the speed of a Blenheim. He called in at Heston to see it and had one of his pilots fly it. When he tried to get the fighter Blenheims which were being delivered to be ‘’Cottonized’ by the manufacturers he was told that it couldn’t be done. Sidney’s engineers were not too busy and he suggested that they could do the work. They modified eight Blenheims in a week and Dowding was delighted. ‘If there is anything I can do for you, let me know’, he said. Sidney took the plunge – ‘Could you lend me a couple of Spitfires?’ The next morning, two Spitfires landed at Heston. (Sidney was on the mat when Peck found out about this. Even Dowding came in for some criticism).

The Spitfires were duly ‘Cottonized’ and the maximum speed went up from 360 to 396 mph. A 29 gallon tank could go under the pilot’s seat and small tanks were squeezed into the leading edges. The range of the PR Spitfire was now 1250 miles. Fitting the camera in the fuselage behind the pilot was more difficult but a solution was found. The prototype Spitfire had a fixed pitch wooden two blade propeller weighing 88 lbs. The metal three blade variable pitch prop which replaced it in later production Spitfires weighed 375 lbs. To balance that, 32 lbs of lead weights were packed in the fuselage behind the tail. These were removed and the weight of the camera restored the balance. A heating duct was fitted reaching the camera’s housing which would prevent condensation. By October 1939 the unit was fully equipped for operations.

Sidney was asked to go to see Air Marshal Arthur (‘Ugly’) Barratt, the C-in-C of the RAF contingent in France. Barratt had only Blenheims and Battles for PR work, flying usually between 5,000 and 10,000 feet but they were frequently intercepted and had been suffering heavy losses. Sidney was confident that his Spitfire was unlikely to be detected at 30,000 ft and that was the case when Shorty Longbottom flew the first high level PR sortie along the whole Siegfried line. The film was rushed back to Heston for processing and revealed another problem.

Sidney Cotton and AM Barrett

Sidney Cotton and AM Barrett

There was no RAF unit capable of producing large quantities of prints. Sidney went to the man who had run his aerial survey business in Newfoundland twenty years before. He now had his own company using up-to-date equipment and trained interpreters operating the most modern Swiss Wild stereoscopic machines. They were now unable to operate in wartime. AVM Peck was adamant that no civilian organization could be employed to do the work and Sidney would have to wait until a proper RAF was set up and trained. Nevertheless, Sidney ignored this ruling, swore the civilians to secrecy and got them to produce and interpret his prints. He also borrowed from them a much longer lens which gave a better scale to photographs taken from 30,000ft

In France, the British forces needed up-to-date information about Belgium. They were convinced that any German attack would avoid the Maginot Line and come through Belgium. The Belgians wanted no incident, however minor, which might infringe their neutrality and had banned any RAF flight over their territory. Sidney’s reaction was typical. The high-flying Spitfire’s cameras covered a wide swathe of territory and ‘the Belgians would never see it anyway’.

Although he was working with just a couple of caravans and one Spitfire he was quite pleased with the results which he showed to AVM Peck at the end of January 1940. Since the outbreak of war the RAF had photographed 2,500 square miles of enemy territory for the loss of 40 aircraft, mostly Blenheims. The French had photographed 6,000 square miles for the loss of 60 aircraft and the Spitfire had photographed 5,000 square miles in just three flights.

Sidney was asked by the Admiralty to photograph Wilhelmshaven to see if the Tirpitz was there. He told the Air Ministry because he was aware the all such requests had to be made at that level. He was surprised to learn how fierce the inter-service rivalry was. He was told that on no account could he deal with the Navy direct. So when he was invited to a meeting with Sir Dudley Pound, the First Sea Lord, to discuss the photographs he assumed his RAF senior officers knew about it. They didn’t. When Sir Richard Peirse came in he asked ‘What are you doing here Cotton?’ His annoyance increased when Sir Dudley Pound asked him to move down the table. Pound wanted Cotton alongside him when they discussed the photographs. In the meeting it became clear that, apart from Peck, none of his senior RAF officers knew that Sidney had been producing such excellent results. Pound even suggested the Navy should take over the unit, a suggestion which did not go down well.

The PR Unit was responding to requests from senior officers at the operational level - the RAF in France, Bomber Command and, of course the Navy. The photographs being produced were transforming their view of the value of properly analysed PR intelligence and the demand for more and wider coverage increased. Yet at the highest level - the Air Ministry in general and the Vice Chief of Air Staff in particular - there appeared to be only resentment at the success of the unit, even obstruction to its further development. They referred to the unit as ‘Cotton’s Club’ or Cotton’s Crooks’. This only encouraged Sidney to use his normal methods of getting things done, personal contacts and under the counter deals. Worse still, if the Air Ministry opposed something Sidney wanted to do, he couldn’t resist doing it.

In France, a mobile processing unit had been set up, conveniently near the French photographic intelligence unit with whom they had good co-operation. AM Barratt released one of his administrative officers to handle the day to day operations of the unit and General Gort, who commanded the British Expeditionary Force, kept Cotton busy. Hearing that the French were seriously concerned that Italy might join the war Sidney called on Pat Martin. She had several Italian friends and Sidney sent her to Rome on ‘intelligence gathering’. She flirted and intrigued her way via social gatherings for any useful information, even, at one point, being propositioned by Mussolini’s son. She came back convinced that Italy would join the war (which they did in June 1940).

Sidney’s little band of pilots were working hard with frequent long flights. He asked Winterbotham if MI6 would rent a flat in Paris so they could relax properly when not on operations. This was appreciated by the pilots. However, it was soon regarded by those in authority as another Cotton transgression. He was later accused of organizing wild parties with too many women. It was referred to as his ‘brothel’. Less well known was the fact that he was also running some of his many businesses and was still acting as agent for his gun-running Mexican friends who were organizing the supply of weapons to the French. Significantly, in his own frequent flights he preferred to use small French airfields wherever possible, away from the scrutiny of the RAF.

In early May, the Germans broke through Belgium and the work of the unit increased. The four Spitfires were often flying five flights a day. In the midst of this, came an unusual request. The French asked for photographs of Baku on the Caspian Sea. If Russia entered the war on the German side, the French intended to bomb the Russian oilfields. A Hudson was prepared and flew to Habbaniya in Iraq. It was given a civilian registration, painted in Camotint and duly carried out its survey flights. In a strange twist, when the Germans occupied France the photographs were seized and used during the attack on Russia.

The German armies were approaching Paris. Winterbotham asked Sidney to take a Hudson to Orly, escorted by two Spitfires. He was to rescue Richard Lewinski, one of the Polish coding experts who had brought the Enigma machine to France. The airport at Orly was crowded with people, all looking for some way out of France. Lewinski and his wife were waiting with their escort, a Commander Dunderdale. When he stepped out of the Hudson Sidney was approached by a man he knew well, Marcel Boussac, a millionaire who had made his fortune in fabrics. He offered a handsome sum of money for the two spare seats on the plane. Sidney said ‘Perhaps we can talk business’. Dunderdale overheard this and was furious. He rang Winterbotham who threatened Sidney with a court martial - or the Tower of London.

Boussac (who was later to found the Dior fashion house) had to walk away and the Hudson left with the Lewinskis aboard. It was no easy flight. England was fog bound and Sidney had to find an alternative airfield. They landed in Jersey and spent the night in a hotel. The following morning, they were wakened by machine gun fire from Messerschmitts strafing St Helier. Fortunately, the Hudson was undamaged and Sidney had it filled with fuel. He headed west far into the Atlantic before turning north and coming up the Bristol Channel finally to reach Heston. He remembered in time that he was attending the wedding of Bob Niven that afternoon. To add to the impact of the day it was his birthday and there was a letter waiting for him.

The letter was from the Air Ministry. They had decided that the unit had ‘passed its development phase’ and would now become part of Coastal Command. It would be commanded by Wg. Cdr Geoffrey Tuttle (Cotton’s deputy). This was a bitter blow for Sidney and a surprise for the staff of the unit. They were all loyal to ‘the best boss they ever had’. They tried to have him awarded a DSO. Naturally, that failed although Sidney was awarded a token OBE in the 1941 Honours List. Tuttle was almost embarrassed to take over the unit. (In later years, after he became Air Marshal Sir Geoffrey Tuttle he still addressed Sidney as ‘Sir’).

Now unemployed, Sidney was posted to RAF Uxbridge but told there was no need for him to live there, so he went home to his flat. He was told that there could be a place for him in the Royal Navy and he should order a uniform. Then he had to cancel it because the Air Ministry heard about it. They refused to supply any aircraft or equipment that the Navy would need to set up a PR unit. Sidney watched the Battle of Britain go by, followed by the nightly bombing of the Blitz. The German bombers seemed to be unmolested in the skies over London. There were no effective night fighters and although searchlights illuminated the bombers, the AA guns seemed to hit nothing. Sidney thought ‘Getting the light and day fighters together could work’.

He sought out an old friend, Bill Helmore. He was a scientist now working with Sir Henry Tizard in the Committee for Scientific Study of Air Defence. The airborne light idea had been mooted before but rejected. Helmore and Cotton thought they could make it work. Sidney first obtained his release from paid service in the RAF but he retained his rank in the Reserve. He and Helmore took out patents in their joint names for their planned light and Sidney started in his usual place – at the top. He wrote to Lord Beaverbrook, the Minister for Aircraft Production.

The eventual result was the release of a Douglas DB-7 which was modified to take Helmore’s powerful light and its two tons of batteries. Sidney worked with his usual drive and urgency and noticed that many senior people he met started by being co-operative, suddenly changing to be difficult or antagonistic. He recognized the hand of the Air Ministry. Then he received a letter saying he was discharged from the project with immediate effect. The next day he went to RAF Hunsden to collect his belongings. He was promptly arrested. Before he released Sidney, the Station Commander apologised and explained that he was ‘only obeying orders’.

Banned by the Air Ministry from working on the Turbinlight, Sidney now he was called to the offices of MI5. He was interviewed by the Director of Intelligence Security, Air Commodore Blackford and two other men, to whom he was not introduced and who stayed silent throughout the meeting. It was obvious that Blackford knew little about the project, and seemed surprised to learn that Sidney had initiated it. A series of probing questions followed to establish Sidney’s movements and who he had been meeting. There were hints that Sidney was being suspected of ‘passing on secrets to a foreign power’. A second meeting was arranged for the following day.

That night, Sidney had dinner with an American he knew who was acting as an envoy for President Roosevelt. He admitted, with some amusement, that they had received a letter from the Air Ministry warning that they should have no dealings with Sidney Cotton. Sidney prepared for the second meeting with MI5. He took letters from Beaverbrook which confirmed his involvement with the project. The ‘foreign power’ incident seemed to be when Sidney had shown the work on the Turbinlight to a group of Americans. He was able to produce a copy of a letter, from the Air Ministry, who had themselves invited the group there.

The MI5 investigation immediately collapsed but Sidney was wary of other actions which might disrupt his life. He took all his personal papers to the Australian High Commissioner and asked him to hold them in safe keeping so that they were available for any future defence. There was an interesting outcome to this affair.

In 1943, Sidney was contacted by Desmond Morton, at the time working in the Ministry of Economic Warfare. In 1940, he had been a personal assistant to Winston Churchill who was then First Lord of the Admiralty. Churchill had seen some of Sidney’s photographs and couldn’t resist needling the Air Ministry about their failure to produce any pictures (which had unwittingly fuelled the Air Ministry’s resentment of Sidney). Morton had heard rumours about Sidney’s banishment and was intrigued. In a series of meetings and lunches, Morton prised out the whole story.

He was appalled to learn how Sidney had been treated by government officials. He told Churchill, now the Prime Minister, who immediately ordered an investigation. Morton started with Arthur Street, who signed the letter which had sacked Sidney from the PRU in 1940. When Churchill heard the full story he wrote a letter to all the ‘interested parties’ officially clearing Sidney of any wrong-doing and giving full credit to his achievements. Morton acknowledged that it was too late for Sidney to get involved again but offered him any help he might need.

It was some years since he had lived with his wife, Joan. She had a flat in London and Sidney occasionally called on her, sometimes with a lavish gift, sometimes to take her out to dinner at the Dorchester. It was his way of saying ’goodbye’. They finally divorced in 1944.

Although he was working with just a couple of caravans and one Spitfire he was quite pleased with the results which he showed to AVM Peck at the end of January 1940. Since the outbreak of war the RAF had photographed 2,500 square miles of enemy territory for the loss of 40 aircraft, mostly Blenheims. The French had photographed 6,000 square miles for the loss of 60 aircraft and the Spitfire had photographed 5,000 square miles in just three flights.

Sidney was asked by the Admiralty to photograph Wilhelmshaven to see if the Tirpitz was there. He told the Air Ministry because he was aware the all such requests had to be made at that level. He was surprised to learn how fierce the inter-service rivalry was. He was told that on no account could he deal with the Navy direct. So when he was invited to a meeting with Sir Dudley Pound, the First Sea Lord, to discuss the photographs he assumed his RAF senior officers knew about it. They didn’t. When Sir Richard Peirse came in he asked ‘What are you doing here Cotton?’ His annoyance increased when Sir Dudley Pound asked him to move down the table. Pound wanted Cotton alongside him when they discussed the photographs. In the meeting it became clear that, apart from Peck, none of his senior RAF officers knew that Sidney had been producing such excellent results. Pound even suggested the Navy should take over the unit, a suggestion which did not go down well.

The PR Unit was responding to requests from senior officers at the operational level - the RAF in France, Bomber Command and, of course the Navy. The photographs being produced were transforming their view of the value of properly analysed PR intelligence and the demand for more and wider coverage increased. Yet at the highest level - the Air Ministry in general and the Vice Chief of Air Staff in particular - there appeared to be only resentment at the success of the unit, even obstruction to its further development. They referred to the unit as ‘Cotton’s Club’ or Cotton’s Crooks’. This only encouraged Sidney to use his normal methods of getting things done, personal contacts and under the counter deals. Worse still, if the Air Ministry opposed something Sidney wanted to do, he couldn’t resist doing it.

In France, a mobile processing unit had been set up, conveniently near the French photographic intelligence unit with whom they had good co-operation. AM Barratt released one of his administrative officers to handle the day to day operations of the unit and General Gort, who commanded the British Expeditionary Force, kept Cotton busy. Hearing that the French were seriously concerned that Italy might join the war Sidney called on Pat Martin. She had several Italian friends and Sidney sent her to Rome on ‘intelligence gathering’. She flirted and intrigued her way via social gatherings for any useful information, even, at one point, being propositioned by Mussolini’s son. She came back convinced that Italy would join the war (which they did in June 1940).

Sidney’s little band of pilots were working hard with frequent long flights. He asked Winterbotham if MI6 would rent a flat in Paris so they could relax properly when not on operations. This was appreciated by the pilots. However, it was soon regarded by those in authority as another Cotton transgression. He was later accused of organizing wild parties with too many women. It was referred to as his ‘brothel’. Less well known was the fact that he was also running some of his many businesses and was still acting as agent for his gun-running Mexican friends who were organizing the supply of weapons to the French. Significantly, in his own frequent flights he preferred to use small French airfields wherever possible, away from the scrutiny of the RAF.

In early May, the Germans broke through Belgium and the work of the unit increased. The four Spitfires were often flying five flights a day. In the midst of this, came an unusual request. The French asked for photographs of Baku on the Caspian Sea. If Russia entered the war on the German side, the French intended to bomb the Russian oilfields. A Hudson was prepared and flew to Habbaniya in Iraq. It was given a civilian registration, painted in Camotint and duly carried out its survey flights. In a strange twist, when the Germans occupied France the photographs were seized and used during the attack on Russia.

The German armies were approaching Paris. Winterbotham asked Sidney to take a Hudson to Orly, escorted by two Spitfires. He was to rescue Richard Lewinski, one of the Polish coding experts who had brought the Enigma machine to France. The airport at Orly was crowded with people, all looking for some way out of France. Lewinski and his wife were waiting with their escort, a Commander Dunderdale. When he stepped out of the Hudson Sidney was approached by a man he knew well, Marcel Boussac, a millionaire who had made his fortune in fabrics. He offered a handsome sum of money for the two spare seats on the plane. Sidney said ‘Perhaps we can talk business’. Dunderdale overheard this and was furious. He rang Winterbotham who threatened Sidney with a court martial - or the Tower of London.