The Polar Flights of Amundsen and Byrd (July 2022)

Reaching the Pole (either North or South) had long been man’s ambition but it wasn’t until the 20th Century dawned that explorers took the challenge seriously enough. It was such a terrible journey, the climate was awful, they were sure that the conditions would be difficult, how would they know that they had reached it - and the only way to get there was to walk. So it caught the world’s attention when Robert Peary, after several years of trekking around Greenland and northern Canada, claimed to have reached the Pole on 6th April 1909. It wasn’t until 1911 that Congress would officially recognize his claim (there was a rival whose claim was rejected), by which time there were two expeditions heading for the South Pole.

On 14th December, 1911, Roald Amundsen’s team were the first men to stand at the South Pole. 35 days later Robert Falcon Scott reached the Norwegians’ tent with its flag flying proudly above it. Ironically, although Scott and his men failed in their quest to be first to reach the Pole and had tragically died on the return journey they were hailed as the heroes. They stole most of the acclamation. And in Britain at least, and in much of the world, the man primarily associated with the South Pole is Captain Scott, not Roald Amundsen.

But not in Norway. Born in 1872, Amundsen was the fourth son of a wealthy shipping magnate and sent to the best schools. His mother insisted he should train as a doctor and he spent three years at university as an indifferent student. He had become fascinated by the exploits of polar travellers, particularly John Franklin who died with all his men in the search for the north west passage in 1845. When his mother died in 1893 he left university and joined a sealing ship to learn navigation in high latitudes and how to cope in Arctic weather. In 1896, he joined a Belgian research ship. When this spent a winter trapped in ice, Amundsen completed his ‘polar’ education.

But not in Norway. Born in 1872, Amundsen was the fourth son of a wealthy shipping magnate and sent to the best schools. His mother insisted he should train as a doctor and he spent three years at university as an indifferent student. He had become fascinated by the exploits of polar travellers, particularly John Franklin who died with all his men in the search for the north west passage in 1845. When his mother died in 1893 he left university and joined a sealing ship to learn navigation in high latitudes and how to cope in Arctic weather. In 1896, he joined a Belgian research ship. When this spent a winter trapped in ice, Amundsen completed his ‘polar’ education.

Amundsen was more properly airborne in April 1913 during a lecture tour in America. His first flight was in a Curtis floatplane and when he came home he began instruction on a Farman Longhorn. His flights were at intervals over several months and just before taking his tests for his licence, he and his instructor experienced a ‘heavy landing’ (well, quite a comprehensive crash).

Undeterred, the next day, 18th September 1915, he took his test and, at the age of 42, became the first Norwegian civilian to qualify for a pilot’s licence. FAI (Norge) Aviator’s Certificate No. 1 was closely followed by a telegram of congratulation from King Haakon VII.

Undeterred, the next day, 18th September 1915, he took his test and, at the age of 42, became the first Norwegian civilian to qualify for a pilot’s licence. FAI (Norge) Aviator’s Certificate No. 1 was closely followed by a telegram of congratulation from King Haakon VII.

Norway was neutral in the 1914-18 war. It benefitted from a shipping boom and Amundsen’s family made enough money to finance’s Roald’s next expedition. He planned a ‘voyage’ - a drift in the frozen sea - towards the pole in the relatively unexplored region north of Russia. He had a special ship built, one with rounded bilges so that it would rise rather than being crushed by the freezing sea. He named it Maude, after the queen. There were reports that he was going to take an aeroplane, a Curtis Oreole, that was being built for him. This didn’t happen. America entered the war in April 1917 and disrupted this plan.

Maude sailed from Tromso on 15 June 1918 without an aeroplane. It drifted, not towards the pole, more along the line of the north-east passage. It eventually emerged from the ice in the spring of 1921 near Alaska. It meant that Amundsen had now achieved a complete circumnavigation of the polar sea and with the vast amount of scientific data which had been collected the expedition was deemed to be a success.

Maude sailed from Tromso on 15 June 1918 without an aeroplane. It drifted, not towards the pole, more along the line of the north-east passage. It eventually emerged from the ice in the spring of 1921 near Alaska. It meant that Amundsen had now achieved a complete circumnavigation of the polar sea and with the vast amount of scientific data which had been collected the expedition was deemed to be a success.

It was delivered to Point Barrow at the wrong time of year and spent the winter bundled up in a shed. Early in May, 1923, it was fitted with skis and test flown. This revealed that the drag of the skis reduced the range by a serious amount. Haakon Hammer, Amundsen’s business manager, went to Svalbard to see whether it was practical to lay down caches of fuel and survival equipment on the ice if the Junkers needed them to finish its journey. But how would they find them?

In Alaska, Amundsen was learning that a heavily loaded ski equipped aeroplane needed a long runway of very smooth ice. These and other difficulties convinced him that the Junkers was not the aeroplane for a cross-polar flight. He had to have a machine that did not use draggy skis or floats yet could take off and land on water, snow and ice. There was such an aeroplane - the Dornier Wal.

In Alaska, Amundsen was learning that a heavily loaded ski equipped aeroplane needed a long runway of very smooth ice. These and other difficulties convinced him that the Junkers was not the aeroplane for a cross-polar flight. He had to have a machine that did not use draggy skis or floats yet could take off and land on water, snow and ice. There was such an aeroplane - the Dornier Wal.

Hammer, an American of Danish origin was an eternal optimist and he went off to Italy where Dornier had his factory (to avoid contravening the terms of the Versailles Treaty). He negotiated the purchase of three Dornier Wal flying boats at $40,000 each. This put Amundsen in a very difficult position. He had no money - he owed his brother $20,000 lent to support a previous expedition. Still in America, he launched on a lecture tour and wrote articles for magazines. That did not raise enough money. The prospect of bankruptcy loomed.

Salvation came out of the blue in the form of a telephone call. Lincoln Ellsworth had first met Amundsen in France during the war and later had shown some interest in joining the Maude expedition (through the north east passage). Now he had a much more interesting proposition. He would provide the bulk of the funding for the next polar venture if he was allowed to go along with it.

Amundsen thought he was rather old at 44 to be launching on his first arctic experience but - he was fit, a qualified pilot and a confident friendly individual who would fit in a team. And he had the money - $85,000. He had negotiated an advance of his inheritance from his millionaire father, who imposed a condition of his own. He insisted that all six crew members of the Wals should have parachutes.

Salvation came out of the blue in the form of a telephone call. Lincoln Ellsworth had first met Amundsen in France during the war and later had shown some interest in joining the Maude expedition (through the north east passage). Now he had a much more interesting proposition. He would provide the bulk of the funding for the next polar venture if he was allowed to go along with it.

Amundsen thought he was rather old at 44 to be launching on his first arctic experience but - he was fit, a qualified pilot and a confident friendly individual who would fit in a team. And he had the money - $85,000. He had negotiated an advance of his inheritance from his millionaire father, who imposed a condition of his own. He insisted that all six crew members of the Wals should have parachutes.

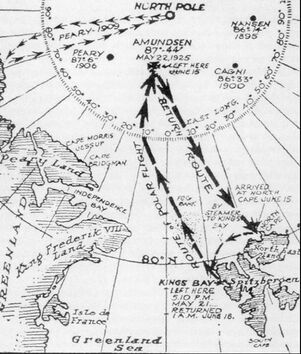

The expedition assembled at King’s Bay in Svalbard in April 1925. The two flying boats, registered N-24 and N-25, arrived as deck cargo on a motor ship and were off loaded at the jetty of the coal mining company (Norwegian and Russian mines had been producing coal since 1916). Amundsen’s aim was not to reach the pole - Peary had done that in 1909 - but to explore the area between Svalbard and the pole. This could include a landing on the ice and the Dorniers carried collapsible sledges, skis, equipment and sufficient food for up to a month on the ice (Ellsworth had to learn to ski).

Navigation would be tricky. The angle of the sun above the often hazy horizon would always be small and the magnetic compass not reliable (so near the pole that the lines of magnetic force would be near vertical). They had sun compasses which were only reliable when the correct time was known. Their three chronometers would be checked with a time signal radioed daily from the Eifel Tower. They had specially made drift meters and, of course, blind flying instruments driven by venturis. Radios had been ordered to check direction of the King’s Bay beacon and to communicate with their base there.

On 21 May all was ready, apart from the radios which had not yet been delivered. Despite this, Amundsen,elected to leave. In retrospect, it seems odd that he did this. Maybe it was because he had spent so many years travelling in the arctic without a radio that he was just reverting to normal practice.

Navigation would be tricky. The angle of the sun above the often hazy horizon would always be small and the magnetic compass not reliable (so near the pole that the lines of magnetic force would be near vertical). They had sun compasses which were only reliable when the correct time was known. Their three chronometers would be checked with a time signal radioed daily from the Eifel Tower. They had specially made drift meters and, of course, blind flying instruments driven by venturis. Radios had been ordered to check direction of the King’s Bay beacon and to communicate with their base there.

On 21 May all was ready, apart from the radios which had not yet been delivered. Despite this, Amundsen,elected to leave. In retrospect, it seems odd that he did this. Maybe it was because he had spent so many years travelling in the arctic without a radio that he was just reverting to normal practice.

The sea was still frozen and N-25, with its two 380 hp RR Eagle engines roaring needed a push-start to taxi down the slope to the sea ice. The normal load for a Wal was 5,700 kgs. Both the Wals were overloaded to 6600 kgs and would not have been able to take off from water, but it was expected that the sea ice could take the load.

It could, though the ice was visibly bending and sea water was rushing into the hollows. After a long run of nearly 50 seconds the pilot, Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen, lifted N-25 off and climbed away. N-24 had slewed through 90° when being pushed down to the ice and this seems to have caused some damage. During the take-off, Leif Dietrichson heard a noise that sounded like rivets popping and the boat began to take in water. He kept going and after a prolonged run of some 1400 metres, the Wal lifted off.

They flew north in loose formation. Amundsen tried his sextant but found that the horizon was so hazy that he could get no useful reading. However, the sun compasses worked well and they held their course. A bank of cloud required them to climb to 3000’ to stay in clear air. They estimated that they had reached 82° north when they cleared the cloud. They expected to find large flat areas of ice suitable for a landing but it was broken in small irregular pieces with thin snakes of water between. It was some hours later that a large lead appeared and Riiser-Larsen lined up for a landing. The sea was largely slush with pieces of floating ice and the N-25 slowed to a stop with the wings passing over bergs which littered the ‘dry’ ice. N-24 found a different lead and Dietrichson swung the boat up onto the ice out of the sea, conscious of the sprung rivets.

They assessed their situation. At 87° 50’ north, they were 528 nm from King’s Bay and 130 nm from the pole. N-24 was likely to sink so they had to rely on N-25 to carry them all home. If they were unable to take off no-one would know where to search for them because without a radio they had had no contact with King’s Bay. They had to transfer N-24’s remaining fuel to N-25 and the boats were at least ¾ of a mile apart. Dietrichson tried to taxi N-24 towards the other boat but the front engine would not start. Even with full throttle on the rear engine and three men pulling the boat would not move. They gave up. Everyone had been awake for more than 24 hours so they had some hot soup and slept.

The next day, or about 090° on the sun compass, the crew of N-24, Dietrichson, Lincoln Ellsworth and Omdal made their way towards N-25, dragging the folding boat loaded with supplies. They made slow progress, climbing over humps of jagged ice and avoiding leads of slushy water. Ellsworth managed to get across one gap between the floes but when Dietrichson followed he slipped and fell into the water. Omdal fell after him, in the process knocking out five teeth. They kicked off their skis and tried to swim against the current which was pulling them under the edge of the sea ice. Ellsworth heard their shouts. He took off his own skis and lay down, spreading his weight over the ice. He held out the skis over the water towards the struggling men. They grabbed the tips and Ellsworth slowly hauled them to safety.

That perilous journey was repeated often in the following days as fuel, food and essential equipment was transferred to N-25. There was a much harder, prolonged task in prospect. It was unlikely that a convenient lead of water, straight and long enough for take off would open up alongside the flying boat. They would have cut and flatten a runway in the wilderness of humps and blocks. Unfortunately they had no suitable tools. Ice was cut with axes and knives and snow stamped down with boots. They worked all and every day, punctuated by three small meals on reduced rations. They slept in any convenient space in the hull of the boat. The temperature was always below freezing point.

Amundsen kept up a routine of keeping records of weather and ice conditions and recalculating their position to record drift. He also took photographs and film to supplement the log of the expedition. Twice he used an explosive device whose echo indicated the depth of the sea. It showed the sea to be 3,750 metres deep. From time to time, they started the engines and did a short take-off/fast taxi run to assess the suitability of the area they had flattened.

It wasn’t until 14th June, by which time Amundsen estimated that they had shifted more than 500 tons of ice, that they thought a take off was possible. They marked the distances down the runway with strips of dark material and loaded only the minimum of essential equipment and the remainder of the food.

It could, though the ice was visibly bending and sea water was rushing into the hollows. After a long run of nearly 50 seconds the pilot, Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen, lifted N-25 off and climbed away. N-24 had slewed through 90° when being pushed down to the ice and this seems to have caused some damage. During the take-off, Leif Dietrichson heard a noise that sounded like rivets popping and the boat began to take in water. He kept going and after a prolonged run of some 1400 metres, the Wal lifted off.

They flew north in loose formation. Amundsen tried his sextant but found that the horizon was so hazy that he could get no useful reading. However, the sun compasses worked well and they held their course. A bank of cloud required them to climb to 3000’ to stay in clear air. They estimated that they had reached 82° north when they cleared the cloud. They expected to find large flat areas of ice suitable for a landing but it was broken in small irregular pieces with thin snakes of water between. It was some hours later that a large lead appeared and Riiser-Larsen lined up for a landing. The sea was largely slush with pieces of floating ice and the N-25 slowed to a stop with the wings passing over bergs which littered the ‘dry’ ice. N-24 found a different lead and Dietrichson swung the boat up onto the ice out of the sea, conscious of the sprung rivets.

They assessed their situation. At 87° 50’ north, they were 528 nm from King’s Bay and 130 nm from the pole. N-24 was likely to sink so they had to rely on N-25 to carry them all home. If they were unable to take off no-one would know where to search for them because without a radio they had had no contact with King’s Bay. They had to transfer N-24’s remaining fuel to N-25 and the boats were at least ¾ of a mile apart. Dietrichson tried to taxi N-24 towards the other boat but the front engine would not start. Even with full throttle on the rear engine and three men pulling the boat would not move. They gave up. Everyone had been awake for more than 24 hours so they had some hot soup and slept.

The next day, or about 090° on the sun compass, the crew of N-24, Dietrichson, Lincoln Ellsworth and Omdal made their way towards N-25, dragging the folding boat loaded with supplies. They made slow progress, climbing over humps of jagged ice and avoiding leads of slushy water. Ellsworth managed to get across one gap between the floes but when Dietrichson followed he slipped and fell into the water. Omdal fell after him, in the process knocking out five teeth. They kicked off their skis and tried to swim against the current which was pulling them under the edge of the sea ice. Ellsworth heard their shouts. He took off his own skis and lay down, spreading his weight over the ice. He held out the skis over the water towards the struggling men. They grabbed the tips and Ellsworth slowly hauled them to safety.

That perilous journey was repeated often in the following days as fuel, food and essential equipment was transferred to N-25. There was a much harder, prolonged task in prospect. It was unlikely that a convenient lead of water, straight and long enough for take off would open up alongside the flying boat. They would have cut and flatten a runway in the wilderness of humps and blocks. Unfortunately they had no suitable tools. Ice was cut with axes and knives and snow stamped down with boots. They worked all and every day, punctuated by three small meals on reduced rations. They slept in any convenient space in the hull of the boat. The temperature was always below freezing point.

Amundsen kept up a routine of keeping records of weather and ice conditions and recalculating their position to record drift. He also took photographs and film to supplement the log of the expedition. Twice he used an explosive device whose echo indicated the depth of the sea. It showed the sea to be 3,750 metres deep. From time to time, they started the engines and did a short take-off/fast taxi run to assess the suitability of the area they had flattened.

It wasn’t until 14th June, by which time Amundsen estimated that they had shifted more than 500 tons of ice, that they thought a take off was possible. They marked the distances down the runway with strips of dark material and loaded only the minimum of essential equipment and the remainder of the food.

Repeated attempts to take off failed. The problem seemed to be that the temperature had risen from its usual minus 12°C to almost 0° and the drag of the slush made the acceleration sluggish. The next day, the temperature had fallen and there was a slight wind, straight down the runway. It was at 2230 on 15th June that N-25 lifted off the ice and Riiser-Larsen set course for Svalbard. Cruising at 80 knots they flew for eight hours, frequently checking the drift, occasionally in fog and at no time did they see anywhere suitable for a landing. They celebrated the first sighting of Spitzbergen by eating all the food. Riiser-Larsen landed in the sea and taxied into a bay. There were just 30 litres of fuel left in the tanks.

Back at King’s Bay on 21st May when the Dornier left there had been little concern when they did not return immediately. It was assumed that they had intentionally landed somewhere on the sea ice. But as the days passed it seemed that the aircraft had been damaged or crashed and that the survivors would be walking out, probably towards Greenland. Amundsen had left some notes about areas to be searched if his party failed to return and two ships set off to cover the edges of the sea ice between Svalbard and Greenland. The Norwegian Navy sent two floatplanes which, although they had only a short range, could carry out repeated searches in the area north of Svalbard. Two ice-breakers searched the sea ice north of Russia. Amundsen had specified that the searches should continue for no longer than six weeks, presumably based on the amount of food carried by the expedition.

On 18th June, there were still two weeks to go when Sjöliv, a small sealer, sailed into King’s Bay with six dirty, bearded gaunt explorers on its deck. The news went around the world and the men who had rescued themselves were hailed as heroes. The first exploration of the Arctic by air had been carried out and both out and return journeys had been by air.

For three days, they slept, surfacing only to eat and read the telegrams of congratulations which flooded in. Ellsworth learned that his father had died unaware that his missing son was alive and well. The N-25 was recovered and put on a ship to be taken to a naval base near Oslo. The explorers followed. They flew in the N-25 and alighted in Oslo harbour. Taken ashore, they were driven through the streets in open carriages to an official reception. Dinner with the king and queen followed where Ellsworth was awarded a gold medal for his action in saving the two involuntary swimmers. In retrospect, it was realised that this had saved the whole expedition because, without the help of Dietrichson and Omda,l the other four men would not have been capable of completing the runway before the food ran out.

As he had done after all his other polar journeys, Amundsen began writing a book. Much of the work had already been done in the comprehensive log he had kept and with the additional notes he had written every day throughout the expedition. At the same time he was working with Ellsworth and the rest of his team planning their next expedition.

The germ of an idea for this had emerged during the search for a suitable aircraft for polar exploration. An airship had come into their sights, specifically the Italian N1, but it was still under construction in 1925. An airship had many advantages over an aeroplane. It had much greater range, needed no special ground surface for landing and take off and, if there were to be any engine trouble, it would carry on flying whilst the engine was being repaired. And in the 20s it was seen as a much safer form of transport than the aeroplane. On the other hand, airships had a modest cruising speed, couldn’t cope with strong winds and needed a large ground handling crew.

Amundsen planned his 1926 expedition to be, initially at least, a repeat of the 1925 flight using this time the Italian N-1 dirigible instead of the Dornier flying boats.. The crew would launch from King’s Bay and fly towards the Pole. Then, with the longer range capability of the airship, they would fly on beyond the Pole and travel all the way to Alaska.

As he had done after all his other polar journeys, Amundsen began writing a book. Much of the work had already been done in the comprehensive log he had kept and with the additional notes he had written every day throughout the expedition. At the same time he was working with Ellsworth and the rest of his team planning their next expedition.

The germ of an idea for this had emerged during the search for a suitable aircraft for polar exploration. An airship had come into their sights, specifically the Italian N1, but it was still under construction in 1925. An airship had many advantages over an aeroplane. It had much greater range, needed no special ground surface for landing and take off and, if there were to be any engine trouble, it would carry on flying whilst the engine was being repaired. And in the 20s it was seen as a much safer form of transport than the aeroplane. On the other hand, airships had a modest cruising speed, couldn’t cope with strong winds and needed a large ground handling crew.

Amundsen planned his 1926 expedition to be, initially at least, a repeat of the 1925 flight using this time the Italian N-1 dirigible instead of the Dornier flying boats.. The crew would launch from King’s Bay and fly towards the Pole. Then, with the longer range capability of the airship, they would fly on beyond the Pole and travel all the way to Alaska.

Lincoln Ellsworth offered most of the money needed to buy the airship and there was a significant contribution from the Aero Club of Norway. The airship builder, Umberto Nobile, offered the use of the airship free of charge provided the Italian flag was flown throughout the flight. Amundsen didn’t want this at all. He intended the airship to be named Norge. to fly the Norwegian flag and to be piloted by his pilot, Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen. Negotiations were prolonged and the serious Norwegians found it difficult to deal with the flamboyant and, some said, ’slippery’ Nobile.

In the end, the airship, with some essential modifications, was bought for only $75,000 of Ellsworth’s $100,000 and Nobile and five Italian crewmen were hired for the flight. The modifications were to remove all passenger accommodation and any non-essential fittings and replace the large control car with a smaller unit to house only the captain, elevator and rudder coxswains, navigator and two radio operators in separate cabins. The soft nose had also to be removed and replaced with a fitting to moor to a mast. Masts were not used in Italy and Nobile had to go the Britain to study those developed by Major George Scott.

In the end, the airship, with some essential modifications, was bought for only $75,000 of Ellsworth’s $100,000 and Nobile and five Italian crewmen were hired for the flight. The modifications were to remove all passenger accommodation and any non-essential fittings and replace the large control car with a smaller unit to house only the captain, elevator and rudder coxswains, navigator and two radio operators in separate cabins. The soft nose had also to be removed and replaced with a fitting to moor to a mast. Masts were not used in Italy and Nobile had to go the Britain to study those developed by Major George Scott.

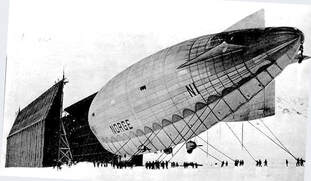

It was pure co-incidence that the Norwegian registration allocated to the airship, N 1, was the same as the manufacturer’s designation, Nobile 1 or N 1. The Norge was a relatively small airship but was still 100 metres long (by comparison the R101 was 235 metres long). The whole ship was a single gas-bag, filled with hydrogen and under it, inside the envelope, hung a rigid metal keel with walkways allowing the crew to move around inside the ship and, incidentally, providing the only flat surfaces on which they could sleep, with a lifebelt for a pillow and a raincoat for bedclothes. The cramped control cabin hung below the keel as did the three Maybach 260 hp engines, each driving a wooden two bladed pusher propeller.

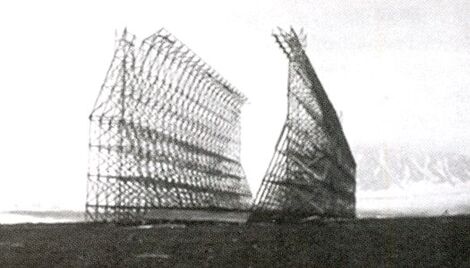

As 1925 was drawing to a close Nobile was modifying the airship and would go on to design and build the mooring masts which were to be erected at Oslo, Vadso in North Norway and King’s Bay. A mast is not a safe housing when strong winds blow so a shed was needed at King’s Bay. This was a huge undertaking and if had to be ready in time for Norge’s arrival in May. The builders would have to work through the Arctic winter.

The last supply ship of the year nudged the calf ice aside as it sailed into King’s Bay on 4th October. On board were the steel bolts and structional components for the shed and generous quantities of cement for its base. Everything was off loaded and taken to the site chosen for the shed. A second, specially chartered, ship arrived carrying tons of timber and other materials. Also off loaded were 32 builders and sufficient food and materials to house them throughout the winter.

As 1925 was drawing to a close Nobile was modifying the airship and would go on to design and build the mooring masts which were to be erected at Oslo, Vadso in North Norway and King’s Bay. A mast is not a safe housing when strong winds blow so a shed was needed at King’s Bay. This was a huge undertaking and if had to be ready in time for Norge’s arrival in May. The builders would have to work through the Arctic winter.

The last supply ship of the year nudged the calf ice aside as it sailed into King’s Bay on 4th October. On board were the steel bolts and structional components for the shed and generous quantities of cement for its base. Everything was off loaded and taken to the site chosen for the shed. A second, specially chartered, ship arrived carrying tons of timber and other materials. Also off loaded were 32 builders and sufficient food and materials to house them throughout the winter.

The last sunset was on 25th October and the work went on under electric lights provided by the mining company’s power plant (when skies were clear there was a little gleam from the moon, which never sets in the Arctic winter). The shed was built in the worst possible conditions, in bitter cold, in snowstorms and gales. When the sun eventually rose, heralding spring, the structure was complete, needing only the covering of sailcloth and canvas doors to be hung.

Deliberately built without a roof its sole purpose was to allow the weightless airship to be grounded safely in strong wind conditions. Without the shed the ship would have been torn from its moorings by even a moderate wind.

All who saw the shed were much impressed by it. Reports of the expedition and Amundsen in his book lavished just praise on the men who had built it in the icy Arctic night.

Deliberately built without a roof its sole purpose was to allow the weightless airship to be grounded safely in strong wind conditions. Without the shed the ship would have been torn from its moorings by even a moderate wind.

All who saw the shed were much impressed by it. Reports of the expedition and Amundsen in his book lavished just praise on the men who had built it in the icy Arctic night.

Amundsen and Ellsworth went on another lecture tour in the US trying to raise more money for the expedition. In Washington they were introduced to Lt. Cdr Richard E Byrd Jnr, a man who had experience of flying in Arctic regions. A graduate of the US Naval Academy he was unfit, because of a sports injury, to carry out normal duties as a naval officer but when America entered the war in 1917 he was called up, learned to fly and became a navigation specialist. He was part of the team which planned the flight of three Curtis flying boats across the Atlantic in 1919, although only one completed the crossing. In 1925 he commanded the aerial unit, three Loening flying boats, that was part of a US Navy expedition to develop practical short wave radios that could operate within the Arctic Circle in the region of the North magnetic pole. Byrd questioned Amundsen and was particularly interested in when the sea ice at Svalbard was suitable for take offs and landings. Clearly, he had plans to return to the Arctic.

Amundsen needed more funds because the Italians had asked for more money - the airship mods and mast building had cost more than expected. They also wanted Nobile’s name to be added to the name of the expedition. Amundsen reluctantly agreed to this but he made it clear that, whilst Nobile was the captain of the airship he, Amundsen, would make all the decisions in how it was operated, i.e. changes of course, where to land, etc.

Once the sea route to Svalbard was open ships arrived with the essential supplies for the flight, 4,800 cylinders of hydrogen, fuel and oil for the engines, clothing and food for the crew, for the flight and for a possible survival camp or trek.

Norge itself, with its mixed Italian/Norwegian crew aboard, left Italy and flew west to avoid having to cross the Alps. They cruised over France at a steady 43 knots, weaving sometimes to take advantage of tailwinds. Landing at Pulham in Norfolk Norge was walked into the shed alongside the R33. Everyone enjoyed their brief but well-fed stay in Pulham - everyone but Titania, Nobile’s pet dog, which he insisted on bringing. She was locked up in quarantine.

The next leg was over a hazy North Sea until Norge climbed above the fog. Then, in perfect weather, they flew to Oslo where they were greeted by flag-waving crowds. The Norwegian flag was flying proudly at the tail but it was noted that a rather larger Italian flag hung on a weighted rope beneath the gondola. A forecast of approaching bad weather caused them to leave after only two hours on the mast.

Amundsen was waiting at King’s Bay. But the first thing to come into view was the smoke of an approaching ship. A radio message confirmed that it was the SS Chantier, the ship being used by Lt. Cdr Byrd to carry a Fokker tri-motor for his attempt to fly to the North Pole.

Amundsen needed more funds because the Italians had asked for more money - the airship mods and mast building had cost more than expected. They also wanted Nobile’s name to be added to the name of the expedition. Amundsen reluctantly agreed to this but he made it clear that, whilst Nobile was the captain of the airship he, Amundsen, would make all the decisions in how it was operated, i.e. changes of course, where to land, etc.

Once the sea route to Svalbard was open ships arrived with the essential supplies for the flight, 4,800 cylinders of hydrogen, fuel and oil for the engines, clothing and food for the crew, for the flight and for a possible survival camp or trek.

Norge itself, with its mixed Italian/Norwegian crew aboard, left Italy and flew west to avoid having to cross the Alps. They cruised over France at a steady 43 knots, weaving sometimes to take advantage of tailwinds. Landing at Pulham in Norfolk Norge was walked into the shed alongside the R33. Everyone enjoyed their brief but well-fed stay in Pulham - everyone but Titania, Nobile’s pet dog, which he insisted on bringing. She was locked up in quarantine.

The next leg was over a hazy North Sea until Norge climbed above the fog. Then, in perfect weather, they flew to Oslo where they were greeted by flag-waving crowds. The Norwegian flag was flying proudly at the tail but it was noted that a rather larger Italian flag hung on a weighted rope beneath the gondola. A forecast of approaching bad weather caused them to leave after only two hours on the mast.

Amundsen was waiting at King’s Bay. But the first thing to come into view was the smoke of an approaching ship. A radio message confirmed that it was the SS Chantier, the ship being used by Lt. Cdr Byrd to carry a Fokker tri-motor for his attempt to fly to the North Pole.

Lt Cdr Richard Byrd

Lt Cdr Richard Byrd

Amundsen was taken by complete surprise. He was aware that Byrd would be planning a Polar flight but didn’t know when it would happen. Now the timing of his arrival at King’s Bay had turned the expeditions into a competition. It didn’t have to be. After all, Peary had been first to reach the Pole and he had done it the hard way, on foot. To Amundsen, the Pole was just a waypoint on his greater journey to Alaska. He deliberately made no comment about Byrd and his venture.

All of the other Norwegians resented Byrd’s timing. Moored at the only dock was Heimal, a Norwegian Navy gunboat which was taking on coal and water. Its captain refused to move to let Chantier dock because, as he said, his instructions were to be available 24 hours a day to lead any rescue operation, should it be needed. Chantier anchored in the harbour. The crew lashed together four lifeboats and built a platform over them. The Fokker was partially dismantled and the ship’s derrick lowered it, piece by piece onto the platform. A fifth lifeboat fended off the ice floes as the platform was rowed to the shore.

All of the other Norwegians resented Byrd’s timing. Moored at the only dock was Heimal, a Norwegian Navy gunboat which was taking on coal and water. Its captain refused to move to let Chantier dock because, as he said, his instructions were to be available 24 hours a day to lead any rescue operation, should it be needed. Chantier anchored in the harbour. The crew lashed together four lifeboats and built a platform over them. The Fokker was partially dismantled and the ship’s derrick lowered it, piece by piece onto the platform. A fifth lifeboat fended off the ice floes as the platform was rowed to the shore.

The Americans set up their camp some distance away from the Norwegians and they worked independently. Both expeditions had signed deals with newspapers for exclusive rights of news and photographs and now a turf war broke out between the rival groups of newsmen since both had easy access to the others’ clients.

Bernt Balchen, one of Amundsen’s men, had previously met and struck up a friendship with Floyd Benet, Byrd’s pilot. Benet was a naval Warrant Officer, a skilled mechanic and pilot and Balchen found him easy-going and modest. Whilst they were chatting Balchen noticed one of Byrd’s Lieutenants waxing the Fokker’s skis. He advised him not to do that because he knew that the snow crystals would stick to the wax and it would be rubbed off. His advice was ignored. The Fokker was tested, failed to accelerate and one of the skis broke off. Amundsen had noticed this incident and diplomatically suggested to Byrd that he might like to borrow Balchen to help with adapting the Fokker to operate in arctic conditions. He had the skis strengthened with strips of hardwood cut from an oar. The planing surface was coated with a mixture of pine tar and resin, burnt in with a blow torch.

Bernt Balchen, one of Amundsen’s men, had previously met and struck up a friendship with Floyd Benet, Byrd’s pilot. Benet was a naval Warrant Officer, a skilled mechanic and pilot and Balchen found him easy-going and modest. Whilst they were chatting Balchen noticed one of Byrd’s Lieutenants waxing the Fokker’s skis. He advised him not to do that because he knew that the snow crystals would stick to the wax and it would be rubbed off. His advice was ignored. The Fokker was tested, failed to accelerate and one of the skis broke off. Amundsen had noticed this incident and diplomatically suggested to Byrd that he might like to borrow Balchen to help with adapting the Fokker to operate in arctic conditions. He had the skis strengthened with strips of hardwood cut from an oar. The planing surface was coated with a mixture of pine tar and resin, burnt in with a blow torch.

The Fokker was named Josephine Ford after the daughter of Edsel Ford, a major sponsor of the flight.

Then a radio message was received. Norge was leaving Vadso on the last leg of its journey to Svalbard. On the approach to the Vadso mast, the port engine had failed. The crankshaft broke. Although there was a spare engine at Vadso Nobile elected to keep ahead of the bad weather and fly on with just two working engines. (An odd decision, which could have ruined the whole expedition. Afterwards, Nobile tried to excuse it because he had been continuously awake and controlling the airship for the previous 31 hours).

They were well out over the open sea and in sight of an iceberg when the wind rose and it began to snow. At this point the starboard engine stopped. The mechanics climbed out and found a ‘broken cross head’. Hanging on to the engine in harnesses, they partially dismantled it, took the broken parts into the ship and kneeling on the narrow walkway, managed to make an effective repair. After two hours in silence, the engine burst into life again and Norge limped on towards Svalbard.

Then a radio message was received. Norge was leaving Vadso on the last leg of its journey to Svalbard. On the approach to the Vadso mast, the port engine had failed. The crankshaft broke. Although there was a spare engine at Vadso Nobile elected to keep ahead of the bad weather and fly on with just two working engines. (An odd decision, which could have ruined the whole expedition. Afterwards, Nobile tried to excuse it because he had been continuously awake and controlling the airship for the previous 31 hours).

They were well out over the open sea and in sight of an iceberg when the wind rose and it began to snow. At this point the starboard engine stopped. The mechanics climbed out and found a ‘broken cross head’. Hanging on to the engine in harnesses, they partially dismantled it, took the broken parts into the ship and kneeling on the narrow walkway, managed to make an effective repair. After two hours in silence, the engine burst into life again and Norge limped on towards Svalbard.

A red balloon was flying overhead to guide the ship to its mooring mast, At its height of 130 ft and with an 8 ton red painted cone on top it was the tallest structure in the Arctic. The wind was light as the airship sank towards the ground and dropped its handling ropes. The mast was not needed. Norge was walked into its shed. Just one gust, short-lived but strong enough to drag the ship and its handling crew sideways, demonstrated the difficulties and danger of ground handling the huge weightless ship.

Work began immediately to repair Norge’s engines, install extra fuel tanks and load the essential supplies for the trans-polar flight. The Norwegians were keen to get to the Pole before the Americans but Amundsen refused to be rushed. In the interests of safety he insisted on great care being taken with every aspect of the flight. Nothing would be loaded aboard that was not essential. Nobile had dress uniforms for the Italians. They were taken off. The crew numbers were reduced and, in selecting who had to be left behind, the crew members were weighed.

Work began immediately to repair Norge’s engines, install extra fuel tanks and load the essential supplies for the trans-polar flight. The Norwegians were keen to get to the Pole before the Americans but Amundsen refused to be rushed. In the interests of safety he insisted on great care being taken with every aspect of the flight. Nothing would be loaded aboard that was not essential. Nobile had dress uniforms for the Italians. They were taken off. The crew numbers were reduced and, in selecting who had to be left behind, the crew members were weighed.

Inevitably, Commander Boyd was ready first and he waited only for the conditions to be right. The weather forecast on 8th May was favourable and around midday Boyd and Floyd Benet said their goodbyes and climbed aboard the Fokker. It was heavily loaded with fuel - in the tanks and in loose cans in the cabin for topping up the tanks - and with food and survival equipment sufficient for a walk to Greenland, including a sledge given to Boyd by Amundsen. The three 200 hp Wright Whirlwind engines were started and the Norwegians watched glumly as Josephine Ford taxied out toward her great adventure which would begin on the narrow strip of sea ice chosen for take off.

In minutes, they were taxying back. The temperature was at its highest around midday and the snow covering on the ice was sticky. The Fokker could not accelerate to take off speed. Once again, Balchen’s advice was sought. The solution was simple. In a few hours, the sun would dip below the horizon and the snow would freeze.

Which, of course, it did and so it was late in the day of 8th May 1926 that the very first aerial ‘assault’ on a Pole was launched when the US Navy team of Lt Cdr Byrd and his pilot, Floyd Bennett, took off from the ice runway at King’s Harbour, Spitzbergen.

In minutes, they were taxying back. The temperature was at its highest around midday and the snow covering on the ice was sticky. The Fokker could not accelerate to take off speed. Once again, Balchen’s advice was sought. The solution was simple. In a few hours, the sun would dip below the horizon and the snow would freeze.

Which, of course, it did and so it was late in the day of 8th May 1926 that the very first aerial ‘assault’ on a Pole was launched when the US Navy team of Lt Cdr Byrd and his pilot, Floyd Bennett, took off from the ice runway at King’s Harbour, Spitzbergen.

Byrd was an expert navigator and used ded reckoning - deduced, reaching conclusions from known facts - and the facts he had were few. He knew exactly where he was when he flew over the pinpoints on the northern coast of Spitzbergen. Once they were left behind nothing that was visible on the shifting ice sheet below had any fixed position on the earth’s surface.

The course was due north but the magnetic compass was not reliable in high latitudes. Much better was the sun compass, essentially a clock with a different dial. It gave an accurate reading of the direction of the sun, provided there weren’t any clouds. To check on any effect on his track of winds, Byrd would constantly be checking the plane’s movement over the ice for angle of drift and speed made good. He passed frequent notes to the pilot in the noisy semi-open cockpit with instructions to change course, once by as little as 3ª.

It is 665 nautical miles from King’s Harbour to the North Pole and Byrd constantly checked how far they had travelled. This could be done only by taking shots with a sextant to measure the angle between the sun and the horizon. Using a sextant in a swaying aeroplane is not easy and once Byrd spent so long trying to get a good shot that he began to suffer from snow blindness. Fortunately, he had brought some amber goggles. Of course, he needed to know exactly how high they were above the surface when he was shooting the sun and altimeter readings vary with variations in air pressure. So Byrd had a barometer to adjust the settings on the wayward altimeter.

From time to time Byrd and Floyd Bennett changed positions, partly for a break but also for Bennett to top up the tanks from the fuel cans stored in the cabin. Empty cans were dropped onto the ice to reduce weight. When he estimated that they still had an hour to go before they reached the pole, Byrd noticed that oil was leaking from the tank behind the starboard engine. Bennett predicted that the engine would soon stop and they wouldn’t get home on two engines. They couldn’t land to fix the leak. There was no flat area for a take off run in sight. The oil pressure didn’t drop and the engine sounded healthy and ran normally. The goal was so near that Byrd decided to press on. (The leak soon stopped. After they got home they found that It was a single rivet in the side of the tank which had worked loose).

Byrd calculated that they reached the pole at 09.02 on 9th May 1926. Floyd Benet turned 90ª for Byrd to take more shots of the sun then they circled the pole taking still photographs and cine. They flew a wider circle, enjoying the date changes that they were experiencing. Byrd went back to his navigation table. Every direction was south - which way was Spitzbergen? Although, at this critical point, the sextant slid off the table and broke its horizon glass the swinging sun compass pointed the way.

The long flight home seemed to go quickly - they must have picked up a tailwind. They could see the bursts of steam from their ship, the Chantier, its hooter whistling a greeting as the Josephine Ford lowered its skis onto the ice runway 15 hours and 30 minutes after its take off. Roald Amundsen was one of the first to offer fulsome congratulations. He had never regarded their two expeditions as being in a race to the pole. His coming flight in the airship Norge had a different and higher goal.

All the nationalities joined in the celebrations. The band from the Norwegian Heimdal played, there were fireworks, rockets and much flag waving. As the Americans congregated in the Chantier with its plentiful supplies of alcohol the Norwegians and Italians turned to the final preparations for their flight to Alaska.

The intention was to launch at about 1.00 a.m. Although the sun was up all day (and ‘night’) it was just after midnight when the air was coolest and most dense, giving the best lift for the airship. On 10th May the day after Byrd’s return to King’s Harbour, everything was ready. But the wind was blowing across the doors and Nobile insisted that it was unsafe to walk Norge out of its shed. As the air warmed up he had to off load 200 kilos of petrol and valve off gas three times.

The course was due north but the magnetic compass was not reliable in high latitudes. Much better was the sun compass, essentially a clock with a different dial. It gave an accurate reading of the direction of the sun, provided there weren’t any clouds. To check on any effect on his track of winds, Byrd would constantly be checking the plane’s movement over the ice for angle of drift and speed made good. He passed frequent notes to the pilot in the noisy semi-open cockpit with instructions to change course, once by as little as 3ª.

It is 665 nautical miles from King’s Harbour to the North Pole and Byrd constantly checked how far they had travelled. This could be done only by taking shots with a sextant to measure the angle between the sun and the horizon. Using a sextant in a swaying aeroplane is not easy and once Byrd spent so long trying to get a good shot that he began to suffer from snow blindness. Fortunately, he had brought some amber goggles. Of course, he needed to know exactly how high they were above the surface when he was shooting the sun and altimeter readings vary with variations in air pressure. So Byrd had a barometer to adjust the settings on the wayward altimeter.

From time to time Byrd and Floyd Bennett changed positions, partly for a break but also for Bennett to top up the tanks from the fuel cans stored in the cabin. Empty cans were dropped onto the ice to reduce weight. When he estimated that they still had an hour to go before they reached the pole, Byrd noticed that oil was leaking from the tank behind the starboard engine. Bennett predicted that the engine would soon stop and they wouldn’t get home on two engines. They couldn’t land to fix the leak. There was no flat area for a take off run in sight. The oil pressure didn’t drop and the engine sounded healthy and ran normally. The goal was so near that Byrd decided to press on. (The leak soon stopped. After they got home they found that It was a single rivet in the side of the tank which had worked loose).

Byrd calculated that they reached the pole at 09.02 on 9th May 1926. Floyd Benet turned 90ª for Byrd to take more shots of the sun then they circled the pole taking still photographs and cine. They flew a wider circle, enjoying the date changes that they were experiencing. Byrd went back to his navigation table. Every direction was south - which way was Spitzbergen? Although, at this critical point, the sextant slid off the table and broke its horizon glass the swinging sun compass pointed the way.

The long flight home seemed to go quickly - they must have picked up a tailwind. They could see the bursts of steam from their ship, the Chantier, its hooter whistling a greeting as the Josephine Ford lowered its skis onto the ice runway 15 hours and 30 minutes after its take off. Roald Amundsen was one of the first to offer fulsome congratulations. He had never regarded their two expeditions as being in a race to the pole. His coming flight in the airship Norge had a different and higher goal.

All the nationalities joined in the celebrations. The band from the Norwegian Heimdal played, there were fireworks, rockets and much flag waving. As the Americans congregated in the Chantier with its plentiful supplies of alcohol the Norwegians and Italians turned to the final preparations for their flight to Alaska.

The intention was to launch at about 1.00 a.m. Although the sun was up all day (and ‘night’) it was just after midnight when the air was coolest and most dense, giving the best lift for the airship. On 10th May the day after Byrd’s return to King’s Harbour, everything was ready. But the wind was blowing across the doors and Nobile insisted that it was unsafe to walk Norge out of its shed. As the air warmed up he had to off load 200 kilos of petrol and valve off gas three times.

It wasn’t until 0800 that Riiser-Larsen, who had been appointed by Amundsen as the airship’s pilot, took charge and in a brief lull in the wind, had the crew walk Norge, backwards, out of the shed. Now that the temperature was rising the airship’s load had to be further reduced. Anything unnecessary was thrown off, duplicated equipment, spare instruments and definitely the full set of dress uniforms which Nobile had brought for the Italians. All the crew members had been weighed and Amundsen reluctantly decided that three of them had be left behind.

One of them was Bernt Balchen. He was approached by Byrd and invited to join him for an unspecified future polar expedition. Balchen had formed a strong bond with Floyd Bennett and that led him to accept Byrd’s invitation - but with reservations. He greatly admired and was loyal to Amundsen, but there was no indication of what he intended to do after the Norge’s flight to Alaska. Secondly, he wasn’t convinced that Byrd had actually reached the North Pole. He knew the exact distance and flight time and if he was right about the Fokker’s cruising speed he calculated that Byrd could not have flown further north than 88ª, 150 nm south of the pole. He wanted to have an opportunity to check that and, hopefully, be re-assured that the claim was genuine.

The records and charts of the flight were assembled for submission to the American National Geographic Society. Byrd and Bennett were to go home to America to a ticker tape parade, the award of Medals of Honor and promotion. They were widely acclaimed to have been the first men to have flown to and around the North Pole.

It was 9.50 am on 11 May 1926 when Nobile called out ‘Hands Off’ and Norge gently lifted into the air. When it reached its pressure altitude of 1200 ft the engines were started and the voyage to another continent was under way.

The best range would be achieved by cruising at 43 knots on just two engines and in 75 hours Norge would travel over 3,200 nautical miles. It was essential, of course, to seek favourable winds. The wireless operator received weather reports and forecasts from Point Barrow in Alaska.

He was also a great help to the navigator in providing bearings from the wireless stations within range and the occasional time signal to check the chronometers and sun compasses.

The best range would be achieved by cruising at 43 knots on just two engines and in 75 hours Norge would travel over 3,200 nautical miles. It was essential, of course, to seek favourable winds. The wireless operator received weather reports and forecasts from Point Barrow in Alaska.

He was also a great help to the navigator in providing bearings from the wireless stations within range and the occasional time signal to check the chronometers and sun compasses.

The slipstream over the ship cooled the gas and made it slightly heavy. Rather than drop ballast, which was in limited supply, Nobile ordered 3ª of up elevator. This increased the angle of attack and provided dynamic lift. But it also increased drag. So maintaining level flight at the best speed was a delicate balancing act.

The riggers continuously patrolled all parts of the ship. One of their jobs was to check the valves on top of the ship to ensure that they were properly seated and not damaged by ice forming on them. One of the riggers climbed out of the hatch at the nose and walked along the top spine of the ship, all in a 40 knot sub-zero wind. Every footstep made a depression in the soft material and as he walked along a wave formed which oscillated and, unchecked, could have thrown him off the ship. The riggers had learned that it was safer to take one long step, followed by two short steps which confused the rhythm of the oscillation..

It was a very bright clear day and they saw an arctic fox and some bear tracks. The ground speed could be checked by timing the movement of the ship’s shadow passing a point on the ice - 29 kts. They climbed and checked again - 37 kts. The best groundspeed, 45 kts, was at 3,600 ft so they stayed at this height. Then it began to snow and they ran into fog. Ice formed on all angles and struts, increasing drag and weight. The propellers launched little projectiles of ice which ripped the fabric covering of the keel and fortunately not the fabric of the gasbag. Nobile climbed until they were clear of the fog. At that point the temperature was -10 °C. At no time during the flight was it warmer than -4°C even in the draught-free control cabin.

As they neared the pole Nobile brought the ship down to 600 ft and throttled back the engines. A sequence of sun shots confirmed the moment that they were over the Pole. At 01.30 GMT on 12 May 1926 the flags of Norway, the United States and Italy were ceremoniously dropped. Amundsen was irritated to see that the Italian flag was much larger that the other two. The relationship between the two men had never been good and now they were trapped together in the crowded freezing gondola it grew increasingly sour. Amundsen later commented that Nobile had turned Norge into ‘a circus wagon of the sky’.

At this point they had completed about one third of their journey. The engines opened up and course was set to the south along the 158°E meridian which would take them to Point Barrow, Alaska. They ran into fog again. It persisted all day. More ice formed and more fabric was ripped, some in the lower panels of the gasbag. The crew patched what they could. They were concerned about the loss of hydrogen, particularly when the ice on the ship made it too dangerous for a crew member to walk on it to check the gas valves.

Eventually the fog cleared and the navigator took a series of sun shots which showed that a crosswind had blown them off course. It needed a change of heading of 13° to counter it. On the morning of the third day, the coast of Alaska was sighted. Their landfall was just west of Point Barrow and Amundsen hoped to land at Nome on the west coast where there would be sufficient numbers of men to act as a landing crew. The direct route crossed a mountain range and the weather had worsened with poor visibility and strengthening winds. They worked their way along the coast as the cloud thickened. Soon they lost all sight of the ground. The sun was hidden so it was not possible to check their position. They climbed for safety and the airship pitched and rolled in the turbulent air.

It was hours before the ground appeared again. They saw a partly frozen sea with whitecaps on the sea between the ice. They were now too far south for the sun to be near the horizon and it couldn’t be seen from the gondola beneath the ship. The navigator had to make the hazardous journey, carrying his sextant, through the nose hatch and up the ladder towards the top of the ship to take his sights.

He calculated that they were over the sea just north of the eastern tip of Russia. It was fortunate that the way to Alaska was downwind. All the crew were exhausted and seriously short of sleep. This latter part of the journey had been the most difficult and tiring of whole trip. When the little settlement of Teller came into view Amundsen decided to land there.

Landing an airship is significantly different from landing an aeroplane and this landing would be particularly difficult. There was no ground crew to hold the ship down in the final stage and there was a strong wind blowing. Nobile headed into the wind and had the elevator lowered to force down the nose. The reaction was, as always, very slow and the crew were told to move along the narrow gangway towards the nose, carrying something heavy. Nobile valved off some of the gas. The ship responded and began to descend. The nose-down angle steadily increased and, even though they had no outside view the men in the nose became alarmed. They ran aft, shouting for Nobile to check the descent. He did - and just in time. Norge settled into level flight little more than 100 feet above the ground.

The crew had prepared a landing bag, a 7 metre long canvas tube with an anchor at one end. At the other end was a rope attached to the nose. The bag was stuffed with boxes of food and spares, weighing overall about 300 kgs. It would be dropped at the last second to lie flat on the ground first, to stop the ship’s forward movement and then to hold the nose into wind.

The riggers continuously patrolled all parts of the ship. One of their jobs was to check the valves on top of the ship to ensure that they were properly seated and not damaged by ice forming on them. One of the riggers climbed out of the hatch at the nose and walked along the top spine of the ship, all in a 40 knot sub-zero wind. Every footstep made a depression in the soft material and as he walked along a wave formed which oscillated and, unchecked, could have thrown him off the ship. The riggers had learned that it was safer to take one long step, followed by two short steps which confused the rhythm of the oscillation..

It was a very bright clear day and they saw an arctic fox and some bear tracks. The ground speed could be checked by timing the movement of the ship’s shadow passing a point on the ice - 29 kts. They climbed and checked again - 37 kts. The best groundspeed, 45 kts, was at 3,600 ft so they stayed at this height. Then it began to snow and they ran into fog. Ice formed on all angles and struts, increasing drag and weight. The propellers launched little projectiles of ice which ripped the fabric covering of the keel and fortunately not the fabric of the gasbag. Nobile climbed until they were clear of the fog. At that point the temperature was -10 °C. At no time during the flight was it warmer than -4°C even in the draught-free control cabin.

As they neared the pole Nobile brought the ship down to 600 ft and throttled back the engines. A sequence of sun shots confirmed the moment that they were over the Pole. At 01.30 GMT on 12 May 1926 the flags of Norway, the United States and Italy were ceremoniously dropped. Amundsen was irritated to see that the Italian flag was much larger that the other two. The relationship between the two men had never been good and now they were trapped together in the crowded freezing gondola it grew increasingly sour. Amundsen later commented that Nobile had turned Norge into ‘a circus wagon of the sky’.

At this point they had completed about one third of their journey. The engines opened up and course was set to the south along the 158°E meridian which would take them to Point Barrow, Alaska. They ran into fog again. It persisted all day. More ice formed and more fabric was ripped, some in the lower panels of the gasbag. The crew patched what they could. They were concerned about the loss of hydrogen, particularly when the ice on the ship made it too dangerous for a crew member to walk on it to check the gas valves.

Eventually the fog cleared and the navigator took a series of sun shots which showed that a crosswind had blown them off course. It needed a change of heading of 13° to counter it. On the morning of the third day, the coast of Alaska was sighted. Their landfall was just west of Point Barrow and Amundsen hoped to land at Nome on the west coast where there would be sufficient numbers of men to act as a landing crew. The direct route crossed a mountain range and the weather had worsened with poor visibility and strengthening winds. They worked their way along the coast as the cloud thickened. Soon they lost all sight of the ground. The sun was hidden so it was not possible to check their position. They climbed for safety and the airship pitched and rolled in the turbulent air.

It was hours before the ground appeared again. They saw a partly frozen sea with whitecaps on the sea between the ice. They were now too far south for the sun to be near the horizon and it couldn’t be seen from the gondola beneath the ship. The navigator had to make the hazardous journey, carrying his sextant, through the nose hatch and up the ladder towards the top of the ship to take his sights.

He calculated that they were over the sea just north of the eastern tip of Russia. It was fortunate that the way to Alaska was downwind. All the crew were exhausted and seriously short of sleep. This latter part of the journey had been the most difficult and tiring of whole trip. When the little settlement of Teller came into view Amundsen decided to land there.

Landing an airship is significantly different from landing an aeroplane and this landing would be particularly difficult. There was no ground crew to hold the ship down in the final stage and there was a strong wind blowing. Nobile headed into the wind and had the elevator lowered to force down the nose. The reaction was, as always, very slow and the crew were told to move along the narrow gangway towards the nose, carrying something heavy. Nobile valved off some of the gas. The ship responded and began to descend. The nose-down angle steadily increased and, even though they had no outside view the men in the nose became alarmed. They ran aft, shouting for Nobile to check the descent. He did - and just in time. Norge settled into level flight little more than 100 feet above the ground.

The crew had prepared a landing bag, a 7 metre long canvas tube with an anchor at one end. At the other end was a rope attached to the nose. The bag was stuffed with boxes of food and spares, weighing overall about 300 kgs. It would be dropped at the last second to lie flat on the ground first, to stop the ship’s forward movement and then to hold the nose into wind.

The crew prepared for the landing to go badly. If the ship hit hard and bounced It could take them up, too high to jump and in an uncontrollable airship short of gas and ballast and with 300 kgs hanging from the nose. They lined up along the walls of the gondola, knives at the ready to slash open the canvas walls and all jump out together. They would all be safe on the ground but the ship would almost certainly blow away and be lost.

It was a happy anti-climax that the landing went off perfectly. The anchor stopped the ship and it sighed gently onto the ice. Nobile pulled the rip panels to release the last of the gas. The 16 men (and Titania, Nobile’s dog) stepped out onto the ice. One of the crew ran out to sever the walkway to the port engine so that it folded neatly and was not driven into the keel.

Norge lay there, deflated but in remarkably good condition.

It was a happy anti-climax that the landing went off perfectly. The anchor stopped the ship and it sighed gently onto the ice. Nobile pulled the rip panels to release the last of the gas. The 16 men (and Titania, Nobile’s dog) stepped out onto the ice. One of the crew ran out to sever the walkway to the port engine so that it folded neatly and was not driven into the keel.

Norge lay there, deflated but in remarkably good condition.

The people of Teller (pop. 250, mostly native Alaskans) welcomed the travellers and gave them some real hot food - three days of gnawing frozen blocks of pemmican or chocolate was unsatisfying nourishment. They slumped into warm beds for as much as 20 hours sleep. Then they set about dismantling Norge, carefully and systematically. It was destined to be transported back to Italy to be rebuilt and fly again. Amundsen and Ellsworth left for Nome where they hired a room. For three weeks, they penned the whole story of the flight. 80,000 words were sent off to the New York Times in return for its sponsorship. Telegrams of congratulation flowed from the US President, from the Kings of Norway and Italy and from many other parts of the world.. A special silver medal was awarded to Amundsen by the US Congress. Nobile was promoted to General by Mussolini.

The team were re-united and sailed south to Seattle. They were welcomed by flag-bedecked and hooting ships, one of which sailed close with the passengers lined on the rails waving Italian tricolours and singing Italian songs. Nobile, wearing a full-dress uniform which he had hidden from Amundsen on the flight, acknowledged the applause with Fascist salutes. The expedition split up, the Norwegians and Italians travelling separately across America, giving talks at many stops on the way, before finally returning to their home countries to the most enthusiastic receptions of all.

There was an aftermath, two years later. Nobile managed to persuade Mussolini to finance another Arctic voyage in an airship. In Italia, an improved development of Norge, he left King’s bay on 23 May 1928 on an exploration of the area north east of Greenland. In bad weather, the ship got into difficulties and crashed heavily onto the ice. The control car with Nobile (and his dog) and eight other men inside it broke off. Another man, who had been killed in the crash, lay on the ice. The damaged and lightened ship rose and blew away, taking six men with it. The survivors’ radio signals were not picked up and the rescue was badly organised.

The team were re-united and sailed south to Seattle. They were welcomed by flag-bedecked and hooting ships, one of which sailed close with the passengers lined on the rails waving Italian tricolours and singing Italian songs. Nobile, wearing a full-dress uniform which he had hidden from Amundsen on the flight, acknowledged the applause with Fascist salutes. The expedition split up, the Norwegians and Italians travelling separately across America, giving talks at many stops on the way, before finally returning to their home countries to the most enthusiastic receptions of all.

There was an aftermath, two years later. Nobile managed to persuade Mussolini to finance another Arctic voyage in an airship. In Italia, an improved development of Norge, he left King’s bay on 23 May 1928 on an exploration of the area north east of Greenland. In bad weather, the ship got into difficulties and crashed heavily onto the ice. The control car with Nobile (and his dog) and eight other men inside it broke off. Another man, who had been killed in the crash, lay on the ice. The damaged and lightened ship rose and blew away, taking six men with it. The survivors’ radio signals were not picked up and the rescue was badly organised.

The Norwegian and Danish authorities sent ships to help in the search and although Mussolini tried to prevent it, Amundsen got involved. He arranged for a French flying boat, a Latham 47, to pick him up at Tromso and fly him to King’s Bay. They took off on 18 June - and disappeared. Months later, a wing-tip float was washed up on the shore. This could have been an appropriate way for Amundsen to die. He is recorded to have said that when he died, he hoped it would be in a chivalrous way - in the great white silence.

The Italia survivors were spotted on 20th June. Nobile was the first to be brought out by a Swedish pilot. Then the weather closed in. The others - and the dog - were rescued piecemeal between 6th and 13th July by aeroplanes and icebreakers.

Back to 1926. The Norge crew were being celebrated on the West Coast and, in New York, Richard Byrd was being raised to the status of a hero. Bernt Balchen was excluded from receptions and other events because he had not been a member of the team at the time of the flight. He was pleased about this - he didn’t like publicity. But when Byrd, Bennett and some of the senior personnel went off on tour he was left behind to look after the Josephine Ford which was to be put on display in a department store. Then the Guggenheim Foundation arranged for the famous Fokker to tour the US - ‘to promote air-mindedness’ Balchen was to be the pilot, along with Floyd Bennett who had persuaded Byrd to release him from the tour.

This gave Balchen the opportunity to check all aspects of the Fokker’s performance and confirm its range and best cruising speeds. He reached the conclusion that Byrd could not have reached the North Pole, as he claimed. He kept this to himself, partly because he did not want to embarrass his friend, Floyd Bennett.

However, Richard Byrd was particularly interested in the range capability of the Fokker. Competitors were assembling to win the Orteig Prize - the trans-Atlantic flight to Paris. This is all outside the main theme of this article, apart from Byrd’s uneasy relationship with Bernt Balchen. It’s sufficient to record that Byrd ordered another Fokker F VII with more powerful engines. He chose a pilot who, it later transpired, couldn’t fly on instruments. Balchen was taken as ‘stand-by pilot and mechanic’. In the flight - which was a few weeks after Lindbergh’s - the pilot lost control in cloud and the Fokker spun. Balchen took over and recovered from the spin. It was another occasion when Byrd was indebted to Balchen whist being aware that Balchen had sufficient grounds to prove his North pole claim to be false and shatter his reputation.

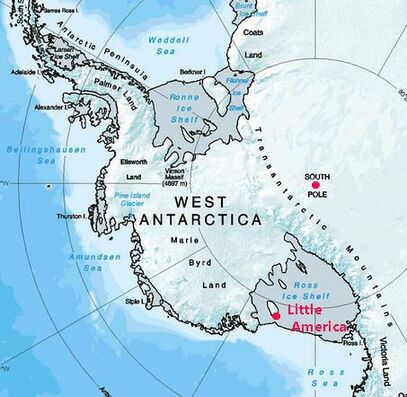

Byrd was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his trans-Atlantic flight. The pilots got no award. They were told it was because they were ‘not military’. Byrd discussed his next plans with them. He was going to fly to the South Pole. He would fly, not a Fokker, but a Ford Tri-motor. It was of all-metal construction (and Henry Ford had made a generous contribution to the expeditions finances). Balchen and Bennett were sent to Detroit to test the Tri-motor.

This gave Balchen the opportunity to check all aspects of the Fokker’s performance and confirm its range and best cruising speeds. He reached the conclusion that Byrd could not have reached the North Pole, as he claimed. He kept this to himself, partly because he did not want to embarrass his friend, Floyd Bennett.

However, Richard Byrd was particularly interested in the range capability of the Fokker. Competitors were assembling to win the Orteig Prize - the trans-Atlantic flight to Paris. This is all outside the main theme of this article, apart from Byrd’s uneasy relationship with Bernt Balchen. It’s sufficient to record that Byrd ordered another Fokker F VII with more powerful engines. He chose a pilot who, it later transpired, couldn’t fly on instruments. Balchen was taken as ‘stand-by pilot and mechanic’. In the flight - which was a few weeks after Lindbergh’s - the pilot lost control in cloud and the Fokker spun. Balchen took over and recovered from the spin. It was another occasion when Byrd was indebted to Balchen whist being aware that Balchen had sufficient grounds to prove his North pole claim to be false and shatter his reputation.

Byrd was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his trans-Atlantic flight. The pilots got no award. They were told it was because they were ‘not military’. Byrd discussed his next plans with them. He was going to fly to the South Pole. He would fly, not a Fokker, but a Ford Tri-motor. It was of all-metal construction (and Henry Ford had made a generous contribution to the expeditions finances). Balchen and Bennett were sent to Detroit to test the Tri-motor.

They were surprised to find that it was fitted with three Wright Whirlwind engines of only 220 hp. To reach the South Pole they would have to climb over the Queen Maud range of mountains, over 11,000 ft high. It was proposed to replace the centre engine with one of the new 525 hp Wright Cyclones. Extra fuel tanks would be needed and Balchen sketched out his design for the skis whose drag would affect the Tri-motor’s performance. When all this work had been done the pilots would take the Tri-motor to northern Canada for testing in Arctic conditions.

Anthony Fokker was annoyed when he learned that Byrd would not be using one of his trusty trimotors to fly to the pole but was somewhat mollified by an order for one of his new Super Universal machines, powered by a 425 hp P&W Wasp. Named Virginia (Byrd’s home state) it would be used for reconnaissance.

The Wasp would also power the expedition’s third aeroplane, a Fairchild FC-2W2, named Stars and Stripes. Its focus would be on photography and filming.

Byrd appointed Balchen in charge of the ‘aviation unit’. Three experienced pilots were recruited. Sadly one of them was not Floyd Bennett. During the testing of the Tri-Motor he had fallen ill, suffering from the after effects of a serious crash in another aeroplane. In hospital, he died. In tribute to their friend and to ensure that he was part of the expedition, in spirit, the Tri-Motor was named Floyd Bennett.

Byrd appointed Balchen in charge of the ‘aviation unit’. Three experienced pilots were recruited. Sadly one of them was not Floyd Bennett. During the testing of the Tri-Motor he had fallen ill, suffering from the after effects of a serious crash in another aeroplane. In hospital, he died. In tribute to their friend and to ensure that he was part of the expedition, in spirit, the Tri-Motor was named Floyd Bennett.

In December 1928 - the beginning of the ‘summer season’- the expedition set sail from New Zealand. Their ship was a fifty year old sealer, a three masted square rigged sailing ship, though fitted also with a steam engine. (It had previously been used by Amundsen in the Arctic). With its 34 inch thick timbers, sheathed with iron bark, it would be their lifeboat in time of trouble. Its name was changed from Viking to the distinctly ill-fiting City of New York. It was loaded with sufficient food and supplies for the crew to spend a year in the ice.

Equipment and supplies were loaded onto the Eleanor Bolling which also had aeroplanes, sleds and dogs as deck cargo. This was the first thin iron-hulled ship to be taken into the icy polar seas. Whilst it did have its moments when dodging ice floes it performed well. On the initial voyage, it towed the slow City of New York when a favourable wind wasn’t blowing then began a shuttle carrying supplies from Dunedin to the ice’s edge.