Arthur Edmond Clouston 1908-1984 (Nov 2015)

Arthur Clouston was running his second hand car business in New Zealand when he heard that Charles Kingsford Smith in Southern Cross was making the first trans-Tasman flight to New Zealand. Driving across the Southern Alps through the night he hoped to reach Christchurch before Smithy landed. He was too late. His consolation was that, since all the spectators had left the airfield, he was free to have an unhurried examination of the Southern Cross. He was so inspired that he immediately joined the Blenheim Flying Club to learn to fly. It soon became evident that he was a natural pilot and he soloed after only 4½ hours.

What next? The New Zealand Air Force in 1932 had an establishment of just six commissioned pilots and offered no career prospect so he sold his car business and travelled to England to apply for an RAF Commission. He found that the process would take months because of the long backlog of applicants. A trawl through an aircraft industry telephone directory resulted in a ‘job’ (£1.50 per week) as a student with Fairey. It kept the wolf from the door and offered valuable experience.

When at last he was called for interview he failed, because of high blood pressure. ‘Come back in a month’ they said. He did – and failed again. Finally, at the third try, he was accepted and soon found himself at No. 3 FTS, Spitalgate. After 2 hours dual, he was sent solo and was immediately upgraded to the senior course. On qualifying, he was posted to 25 Sqn, then flying Hawker Furies. When it was 25’s turn to perform at the Hendon Air Display Clouston was one of the pilots chosen to fly in the difficult tied-together formation, looping and rolling their Furies.

At the end of his four-year commission, he was offered a 10 year extension He refused this, intending to return to New Zealand to become an airline pilot. The Air Ministry countered with a unique job offer. Test pilot posts at Farnborough were normally filled by service officers on a two-year posting. Clouston was asked to go there as the first civilian permanent test pilot. He gladly seized the opportunity to fly a wide range of types, to and beyond normally acceptable limits.

One of these was the noisy, vibrating and cumbersome Avro Rota gyroplane. It was a hardly a practical aeroplane with its blades set at a fixed angle. A small cine camera was fixed to the hub to study the behaviour of the flexing blades. Then Clouston was contacted by Raoul Hafner, an Austrian who was working in England. He had built a new kind of autogyro and wanted Clouston to test it.

He agreed to do this at weekends and found that the controllable angle of incidence of Hafner’s rotor transformed the gyroplane’s handling. It was hired by the RAE for extensive testing and Hafner’s cyclic and collective pitch control of rotors became incorporated into all subsequent gyroplanes and helicopters. (Hafner later became Chief Designer at Bristol Helicopters and Technical Director at Westland).

The Airspeed Courier was the first British commercial aeroplane to be fitted with a retractable undercarriage. The Air Ministry bought one for research into airframe icing which was not well understood. Clouston and his scientific assistant deliberately sought out cu-nim clouds, normally avoided by all sensible pilots. In the cloud they encountered severe turbulence, hail and lightning. As ice built up on the wings, their research would often be interrupted by engine failure, followed by a long glide to earth and a dead-stick landing. No fault could find with the engine but it happened so frequently that the engineers became sceptical of Clouston’s forced landings.

hen, after one landing back at the airfield, they noticed water dripping from the carburettor intakes. It was from the melting ice that had blocked the air intake.

hen, after one landing back at the airfield, they noticed water dripping from the carburettor intakes. It was from the melting ice that had blocked the air intake.

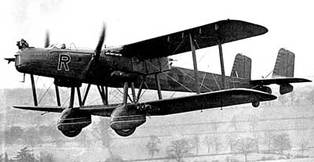

A more suitable aeroplane for their work was the Handley Page Heyford. Its two engines gave a greater margin of safety and its carburettors were mounted alongside warm engine oil. It proved to be very effective in attracting so much ice on its wings and struts that the accumulated weight caused the bomber to sink earthwards despite full power from the engines. As the ice melted at lower levels, chunks of ice would break off and be flung sideways by the propellors. Unfortunately, these were in line with the pilot’s seat and Clouston suffered many bruises including one blow which briefly knocked him out.

The trials were completed using a Northrop 2E with a powerful 1200 hp engine. Much was learned about the conditions in which ice forms and the development of suitable counter measures including inflatable rubber boots and anti-freeze mixture fed onto the wing leading edge.

The trials were completed using a Northrop 2E with a powerful 1200 hp engine. Much was learned about the conditions in which ice forms and the development of suitable counter measures including inflatable rubber boots and anti-freeze mixture fed onto the wing leading edge.

Alongside his work as a test pilot, Clouston became interested in private flying and enjoyed flying his own Aeronca C.3. When the Flying Flea craze swept Britain he felt he had to try one. He borrowed a Flea which had flown successfully behind a Scott motorcycle engine. After a long run it clambered into the air and Clouston coaxed it up to 600 feet, probably a record for the Flea. With only the adjustment of the angle of the forward wing and a large rudder for skidding turns he found the Flea ‘treacherous to manœuvre’ and closed the throttle to glide down. Instantly the Flea turned upside down. The ‘control’ flopped about and he pulled on the trailing edge of the wing. Nothing worked. He opened the throttle wide and the Flea righted itself just 100 feet from the ground. He kept the throttle fully open until he landed. A careful check showed that the CG was too far aft.

Undeterred by this experience he offered to help a man who had set up a business making Fleas. He had a long order book from people who wanted a signed statement that their Flea had actually flown. Clouston agreed to take off, fly a half circuit and land for £5 a time. The first two flights earned him £10 in less than 10 minutes. After the third take-off, the engine lost power and, with nowhere else to land, he dropped into someone’s back garden. The Flea rolled a few yards and ended by demolishing an outside lavatory. When the irate owner approached, Clouston thought than any publicity would not help his career so he jumped over the fence and ran. Nevertheless, he was paid £2 10 shillings for the half flight.

Undeterred by this experience he offered to help a man who had set up a business making Fleas. He had a long order book from people who wanted a signed statement that their Flea had actually flown. Clouston agreed to take off, fly a half circuit and land for £5 a time. The first two flights earned him £10 in less than 10 minutes. After the third take-off, the engine lost power and, with nowhere else to land, he dropped into someone’s back garden. The Flea rolled a few yards and ended by demolishing an outside lavatory. When the irate owner approached, Clouston thought than any publicity would not help his career so he jumped over the fence and ran. Nevertheless, he was paid £2 10 shillings for the half flight.

As the likelihood of war increased Farnborough began research into the use of balloon barrages to deter enemy bombers. They needed to know what would happen when an aircraft flew into a wire. Clouston began the tests with a Miles Hawk trainer, throwing overboard a fishing line attached to a parachute. When he flew into the line it caught on the wing. The aircraft skidded slightly but, before the parachute broke away the friction raised smoke and left a slot in the leading edge several inches deep. Some-times, the line would whip around the wing and ailerons making control difficult.

When it once caught in the propeller the gyrating parachute wrapped the line around the elevator and rudder. Control became impossible and Clouston realised that they had to abandon the Hawk. His passenger happened to be on his first flight and when told to jump he refused, burying his head in the cockpit. Clouston passed him a scribbled note ‘Machine out of control. You must jump’. The frightened passenger undid his harness and got one leg over the side. At that point, the line broke and the controls freed. ‘Sit down’ shouted Clouston. The young scientist became more confused and continued to climb out of the cockpit. Luckily, his parachute pack caught on the side of the cockpit. Clouston loosened his own straps and grabbed the scientist’s flying suit. Eventually, he climbed back in. On landing he said ‘I knew the aeroplane was a bit frisky but I thought that was your flying’.

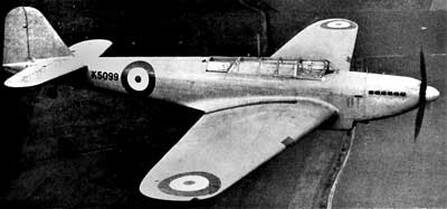

The tests continued using a more robust aeroplane, the Fairey P.4/34, the prototype of a light bomber. The metal wing coped easily with the fishing line so a thin metal line could be used. This was thrown out at 10,000 ft and was quite difficult to see. It often clung to the aeroplane in places where it was hard for Clouston to get rid of it and he would return to land with several hundred feet trailing behind. He tore out telephone cables, fused high tension wires and once pulled away the staging of some painters who were working on second floor windows. Then he collected a cycle rack and dropped eight bikes at intervals along the runway.

On one flight he flew into the cable at 170 mph and the cable caught the tip of one propeller blade. It whirled round, leaving deep gashes around the fuselage. A steel mesh canopy was made to protect him from decapitation. The scientists said that it would be foolish to risk the lives of two people so Clouston would fly solo on future tests. He was moved to Norfolk and wires were dangled from a barrage balloon positioned over open scrubland. Flying into thicker wire made the aeroplane very difficult to control and it often cut into the main spar before breaking off. When they decided that they had learned enough about the effect on the enemy they turned to protecting friendly aeroplanes. A sheath of steel on the leading edge made the wire slide towards the tip and special cutters, triggered by a cartridge were fitted on the wings. At the end of this perilous work, Clouston was deservedly awarded the AFC.

Apart from periods of leave for his long-distance record flying his test flying work continued. When war broke out he was recalled to the RAF as a Squadron Leader, still based at Farnborough. In 1940, when carrying out a test he saw a Heinkel and, although his Spitfire was unarmed, he chased the German all the way to the coast. Later it was thought prudent to arm the Farnborough fighters, purely for defence. Although he was strongly discouraged from any offensive action Clouston managed to shoot down a Heinkel and damage an Me 110.

He began tests to improve night fighters’ ability to see enemy aeroplanes. Flares on long cables were trailed behind a Hampden, flares were attached and lit – just once - to the under-wing bomb racks, photo-flash flares were fired forwards out of a rigged up gun - until one jammed and the fumes nearly asphyxiated the scientists - and finally a Helmore airborne searchlight was fitted in the nose of a Douglas Havoc to allow an accompanying fighter to shoot down the enemy. All proved useless although the experiments did pave the way for the Leigh Light that was fitted for anti-submarine attacks.

It seemed appropriate that when Clouston’s pleas to join an operational unit were successful in 1942 he was posted to 224 Squadron of Coastal Command, flying Liberators. When Leigh Lights came to be fitted, Clouston did the first operational tests.

Apart from periods of leave for his long-distance record flying his test flying work continued. When war broke out he was recalled to the RAF as a Squadron Leader, still based at Farnborough. In 1940, when carrying out a test he saw a Heinkel and, although his Spitfire was unarmed, he chased the German all the way to the coast. Later it was thought prudent to arm the Farnborough fighters, purely for defence. Although he was strongly discouraged from any offensive action Clouston managed to shoot down a Heinkel and damage an Me 110.

He began tests to improve night fighters’ ability to see enemy aeroplanes. Flares on long cables were trailed behind a Hampden, flares were attached and lit – just once - to the under-wing bomb racks, photo-flash flares were fired forwards out of a rigged up gun - until one jammed and the fumes nearly asphyxiated the scientists - and finally a Helmore airborne searchlight was fitted in the nose of a Douglas Havoc to allow an accompanying fighter to shoot down the enemy. All proved useless although the experiments did pave the way for the Leigh Light that was fitted for anti-submarine attacks.

It seemed appropriate that when Clouston’s pleas to join an operational unit were successful in 1942 he was posted to 224 Squadron of Coastal Command, flying Liberators. When Leigh Lights came to be fitted, Clouston did the first operational tests.

It was a dangerous time in the Bay of Biscay and Clouston took his share of the long 14 hour patrols. Ju 88s operated in packs and Clouston met a formation of five who took turns to attack his Liberator. Soon the gunners’ ammunition was exhausted and the only defence was by twisting and turning the heavy bomber. It was fifty minutes before the fighters broke away leaving Clouston and his co-pilot exhausted with aching arms and shoulders but with an intact Liberator.

When new American-built radar sets arrived the results were not good. Clouston invited the US officer attached to the squadron to fly on a patrol – unofficially, of course. He adjusted the radar so that it was working perfectly. He identified a rain squall in the distance and, under it, a U-boat on the surface. Clouston lined up for an attack. Diving out of the cloud at 1000 ft his depth charges straddled the sub which pitched vertically and sank.

After two years with 224 Squadron, Clouston was promoted to Group Captain and posted to a new station at Langham in Norfolk. It was to house two Beaufighter squadrons, one Australian, one New Zealanders. Although he wanted to fly on operations with his crews, he was firmly grounded.

When the war came to an end Clouston was immediately posted to Germany to take over a wartime airstrip with steel plate runways. This was Bückeberg, which was to be developed into a Headquarters and transport hub, using an unwilling workforce of 800 German soldiers. Clouston was again offered a permanent commission which, this time, he decided to accept. Shortly afterwards, the New Zealand Government invited him to become the Director-General of Civil Aviation. The Air Ministry refused to release him for this but did send him on a 2½ year posting to the RNZAF.

When new American-built radar sets arrived the results were not good. Clouston invited the US officer attached to the squadron to fly on a patrol – unofficially, of course. He adjusted the radar so that it was working perfectly. He identified a rain squall in the distance and, under it, a U-boat on the surface. Clouston lined up for an attack. Diving out of the cloud at 1000 ft his depth charges straddled the sub which pitched vertically and sank.

After two years with 224 Squadron, Clouston was promoted to Group Captain and posted to a new station at Langham in Norfolk. It was to house two Beaufighter squadrons, one Australian, one New Zealanders. Although he wanted to fly on operations with his crews, he was firmly grounded.

When the war came to an end Clouston was immediately posted to Germany to take over a wartime airstrip with steel plate runways. This was Bückeberg, which was to be developed into a Headquarters and transport hub, using an unwilling workforce of 800 German soldiers. Clouston was again offered a permanent commission which, this time, he decided to accept. Shortly afterwards, the New Zealand Government invited him to become the Director-General of Civil Aviation. The Air Ministry refused to release him for this but did send him on a 2½ year posting to the RNZAF.

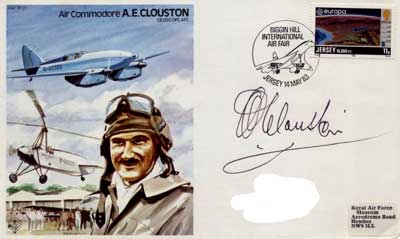

The rest of his career included commanding a night fighter OTU, Commandant of the Empire Test Pilots’ School, and finally, Commandant of the A&AEE, Boscombe Down. He retired in 1960 as an Air Commodore, CB DSO DFC AFC and went to live in Cornwall in a house named ‘Wings’.

The rest of his career included commanding a night fighter OTU, Commandant of the Empire Test Pilots’ School, and finally, Commandant of the A&AEE, Boscombe Down. He retired in 1960 as an Air Commodore, CB DSO DFC AFC and went to live in Cornwall in a house named ‘Wings’.