Amelia Earhart (1897 – 1937) (Oct 2018)

She was, and probably still is, America’s most famous ‘aviatrix’. Yet she was never a particularly skilled or natural pilot. She was 23 before she took her first flight. She found that just being airborne was so exciting that she became determined to become a pilot.

Her upbringing had been somewhat fractured. Her father, qualified as a lawyer, had changed jobs frequently and the family lived in several states so Amelia’s education was partly at home and partly from short periods in local schools. Although intelligent and confident she gathered few close friends and was seen as a loner. She developed an interest in the achievements of successful women and although by no means a militant feminist she felt that women should play a larger part in the running of what was clearly ‘a man’s world’.

Her upbringing had been somewhat fractured. Her father, qualified as a lawyer, had changed jobs frequently and the family lived in several states so Amelia’s education was partly at home and partly from short periods in local schools. Although intelligent and confident she gathered few close friends and was seen as a loner. She developed an interest in the achievements of successful women and although by no means a militant feminist she felt that women should play a larger part in the running of what was clearly ‘a man’s world’.

Thus it was that she deliberately chose a woman to teach her to fly. Mary Anita Snook, known as Neta, was a pioneer aviator who had been flying since before the war (that’s 1917 in the USA). She agreed to give Amelia lessons for $1 a minute in the air, paid in Liberty bonds from Amelia’s savings. (Amelia's ‘regular’ earnings came from two part-time jobs but mainly from the haulage of gravel for a construction company in an old truck which she had bought cheaply on an impulse).

The Canary and Neta Snook

The Canary and Neta Snook

She still hadn’t gone solo when she decided that she couldn’t be a real flier until she had her own plane. The airfield was owned by Bert Kinner, a motor mechanic and Cadillac dealer. He had built a plane and an engine and taught himself to fly. Several crashes later, the single seater had become a two seater. It was not in top condition and its engine was unreliable. But it was available and provided Amelia would allow Kinner the use of the plane ‘for demonstrations’. The price was attractive.

Neta was not happy. She didn’t think the tiny 17 ft span Airster was suitable or safe. She offered to teach Amelia all over again for free. The plane was repainted bright yellow and named ‘The Canary’. There were the usual ‘crack ups’ and forced landings, of course. Amelia eventually soloed in the Canary (which broke a shock absorber on take-off causing a ‘thoroughly rotten landing’).

Neta was not happy. She didn’t think the tiny 17 ft span Airster was suitable or safe. She offered to teach Amelia all over again for free. The plane was repainted bright yellow and named ‘The Canary’. There were the usual ‘crack ups’ and forced landings, of course. Amelia eventually soloed in the Canary (which broke a shock absorber on take-off causing a ‘thoroughly rotten landing’).

Then Neta got married and gave up flying so Amelia went across the road to another flying school and learned ‘air navigation and aerobatics’ – in a Canuck (a Canadian-built Jenny). Between lessons, she asked for a sealed barograph to be placed in the Canary saying she was going to ‘calibrate the ceiling’. She climbed steadily until the Canary’s motor faltered. In an open cockpit, without oxygen, she had reached 14,000 ft and could claim the Woman’s Altitude Record. It was a cloudy and rather foggy day and she decided to come down quickly. She kicked the Canary into a spin and held it there until she could see the ground, less than 3,000 ft below. She was suitably embarrassed when the dangers of this manoeuvre were pointed out by more experienced pilots. Seven months later, on 15th May 1923 she was issued with an FAI Pilot’s Licence, the sixteenth woman in the world to receive one.

By 1925, Amelia’s parents had divorced and she was living near Boston employed as a social worker in a settlement house – a reformist movement experiment to bring together the rich and the poor. She was still flying, when she could afford it, and had joined the local chapter of the National Aeronautic Association. Her keenness and energy got her elected as the Vice-President of the chapter. At the same time, she was acting as Bert Kinner’s sales representative although he was still having trouble with his new 5-cylinder engine so she hadn’t much to sell.

One day, Amelia got a phone call from a Capt. Railey, an ex-Army pilot and PR man. He asked her if she would like to fly the Atlantic. It was just months after Lindbergh’s famous flight. Although wary of a hoax she agreed to see him in his Boston office.

At the interview, the story emerged. Amy Guest was heir to a Pittsburgh steel fortune and had married an Englishman who happened to be the Air Minister. Amy had bought Friendship, the Fokker Trimotor which Admiral Byrd had used in his flight in search of the North Pole. She planned to use it to become the first woman to fly across the Atlantic to ‘unite our two countries’. Unfortunately for her, the family had put down its collective foot. Nevertheless Amy was intent on furthering the cause of women and was looking for a suitable replacement. She asked Admiral Byrd to organise the project. He was an occasional visitor to the Boston NAA, had noticed Amelia and thought she could be right for the role.

Amelia thought so too and eagerly signed the contract. This made her ‘captain of the flight’ and her decisions would be final. The pilots would be hired and paid but any money Amelia earned from royalties or advertising would be given to the fund. She was sworn to secrecy.

Byrd chose Bill Stultz and Slim Gordon as pilot and co-pilot. Both were experienced and capable. The rest of the organising he handed over to the man who had published his book, George Putnam. The Friendship had been serviced and fitted with floats. It was moored in Boston harbour waiting for the right weather forecast. Two other women were believed to be planning a trans-Atlantic flight so there was some urgency to leave at the earliest opportunity.

May and June dragged slowly by. On 1st July, Amelia was told to book into a Boston hotel. She took her normal flying clothes, breeches, lace up boots, leather jacket plus a borrowed flying suit. She was wakened at 3.30 am and driven to the harbour. The crew were taken to the Friendship by a tug boat.

By 1925, Amelia’s parents had divorced and she was living near Boston employed as a social worker in a settlement house – a reformist movement experiment to bring together the rich and the poor. She was still flying, when she could afford it, and had joined the local chapter of the National Aeronautic Association. Her keenness and energy got her elected as the Vice-President of the chapter. At the same time, she was acting as Bert Kinner’s sales representative although he was still having trouble with his new 5-cylinder engine so she hadn’t much to sell.

One day, Amelia got a phone call from a Capt. Railey, an ex-Army pilot and PR man. He asked her if she would like to fly the Atlantic. It was just months after Lindbergh’s famous flight. Although wary of a hoax she agreed to see him in his Boston office.

At the interview, the story emerged. Amy Guest was heir to a Pittsburgh steel fortune and had married an Englishman who happened to be the Air Minister. Amy had bought Friendship, the Fokker Trimotor which Admiral Byrd had used in his flight in search of the North Pole. She planned to use it to become the first woman to fly across the Atlantic to ‘unite our two countries’. Unfortunately for her, the family had put down its collective foot. Nevertheless Amy was intent on furthering the cause of women and was looking for a suitable replacement. She asked Admiral Byrd to organise the project. He was an occasional visitor to the Boston NAA, had noticed Amelia and thought she could be right for the role.

Amelia thought so too and eagerly signed the contract. This made her ‘captain of the flight’ and her decisions would be final. The pilots would be hired and paid but any money Amelia earned from royalties or advertising would be given to the fund. She was sworn to secrecy.

Byrd chose Bill Stultz and Slim Gordon as pilot and co-pilot. Both were experienced and capable. The rest of the organising he handed over to the man who had published his book, George Putnam. The Friendship had been serviced and fitted with floats. It was moored in Boston harbour waiting for the right weather forecast. Two other women were believed to be planning a trans-Atlantic flight so there was some urgency to leave at the earliest opportunity.

May and June dragged slowly by. On 1st July, Amelia was told to book into a Boston hotel. She took her normal flying clothes, breeches, lace up boots, leather jacket plus a borrowed flying suit. She was wakened at 3.30 am and driven to the harbour. The crew were taken to the Friendship by a tug boat.

The first attempt at take-off was a failure. The plane stuck to the glassy water. Stultz taxied back and they threw out some of the spare tins of gasoline. By this time a breeze was ruffling the water and after a long run the Friendship lifted and was on its way. The watchers on the tug had not seen what was going in inside the plane during the take-off. During the dumping of the fuel cans the door latch had been broken. Amelia held the door shut until Slim Gordon came back, attached a rope and tied it to another heavy gas can.

Once in the air, the increasing slipstream forced the door open and the can, with Amelia hanging on, was dragged across the cabin floor. Her cries weren’t heard by the pilots but, luckily, Slim noticed the crisis in the cabin and rushed back to tie the door more securely. He returned to his seat and Amelia sat on a can and began keeping the log which she had been warned she would have to turn into a book after the flight.

Once in the air, the increasing slipstream forced the door open and the can, with Amelia hanging on, was dragged across the cabin floor. Her cries weren’t heard by the pilots but, luckily, Slim noticed the crisis in the cabin and rushed back to tie the door more securely. He returned to his seat and Amelia sat on a can and began keeping the log which she had been warned she would have to turn into a book after the flight.

Flying along the coast of Nova Scotia they ran into heavy fog. Stultz turned back a little way and landed in Halifax harbour to get an up dated weather forecast. After a few hours, they tested the fog again but had to return to Halifax where they spent the night in a small hotel. The next day they were able to fly on to Trepassey, a small fishing port on the south east tip of Newfoundland. And there they were stuck for the next thirteen days.

Several times, when the weather relented, they tried to rise from the choppy waters of the bay. After each attempt more equipment and fuel was ditched, to no avail. The pilots even taxied the plane onto a beach to overhaul the engines between tides. Another problem emerged.

It became evident that Stultz was an alcoholic. Whilst Slim Gordon and Amelia played cards Stultz retired to his room with a bottle. The cables between Trepassey and Putnam grew more agitated until Amelia decided to use the terms of her contract and take charge. On a day when the weather seemed to allow an attempt to take off she and Slim hauled the snoring Schultz out of bed into a cold shower. They fed him copious cups of black coffee and dragged him down to the harbour and Into Friendship. By the time the final loading and take off checks were finished the surly Shultz seemed sober enough to go.

It took four attempts to get airborne but finally, they were on their way, sixteen days after they had left Boston. For an Atlantic flight nothing unusual happened apart from having to arrange time for Stultz to sleep off his hangover. They had the normal problem of dodging build ups of cloud to find clear air, the radio died and they worried about their navigation until they saw land. They followed the coast until they came down to taxi into Burry Port in South Wales after a flight of 20 hours, 40 minutes. The next day they flew on to Southampton and Amelia at last had a chance to take control and fly the Friendship.

In the first official photograph of the welcoming party Amelia is flanked by Slim Gordon and Stultz (in the flying suit). Alongside is Mrs Foster Welch, the Mayor of Southampton. She was the first of many dignitaries to meet Amelia on a whirlwind tour of England – Amy Guest of course, who had paid for everything, Lady Astor, Bernard Shaw, even the Prince of Wales. The pilots tagged along.

Amelia found time to meet Lady Mary Heath who had flown an Avro Avian from South Africa to England. She took a fancy to the Avian and asked George Putnam to buy it and have it shipped to America. They all sailed home on the SS Roosevelt.

Putnam’s organisation had been working hard. All of New York seemed to have congregated to greet Amelia - spraying fireboats, playing bands and the ultimate acknowledgement of fame, a ticker tape parade. Three days in New York, two days in Boston, Williamsburg, Chicago, Toledo . . . Amelia had leapt from weekend club flyer to international heroine just for being, as she put it, ‘no better than a sack of potatoes’.

Several times, when the weather relented, they tried to rise from the choppy waters of the bay. After each attempt more equipment and fuel was ditched, to no avail. The pilots even taxied the plane onto a beach to overhaul the engines between tides. Another problem emerged.

It became evident that Stultz was an alcoholic. Whilst Slim Gordon and Amelia played cards Stultz retired to his room with a bottle. The cables between Trepassey and Putnam grew more agitated until Amelia decided to use the terms of her contract and take charge. On a day when the weather seemed to allow an attempt to take off she and Slim hauled the snoring Schultz out of bed into a cold shower. They fed him copious cups of black coffee and dragged him down to the harbour and Into Friendship. By the time the final loading and take off checks were finished the surly Shultz seemed sober enough to go.

It took four attempts to get airborne but finally, they were on their way, sixteen days after they had left Boston. For an Atlantic flight nothing unusual happened apart from having to arrange time for Stultz to sleep off his hangover. They had the normal problem of dodging build ups of cloud to find clear air, the radio died and they worried about their navigation until they saw land. They followed the coast until they came down to taxi into Burry Port in South Wales after a flight of 20 hours, 40 minutes. The next day they flew on to Southampton and Amelia at last had a chance to take control and fly the Friendship.

In the first official photograph of the welcoming party Amelia is flanked by Slim Gordon and Stultz (in the flying suit). Alongside is Mrs Foster Welch, the Mayor of Southampton. She was the first of many dignitaries to meet Amelia on a whirlwind tour of England – Amy Guest of course, who had paid for everything, Lady Astor, Bernard Shaw, even the Prince of Wales. The pilots tagged along.

Amelia found time to meet Lady Mary Heath who had flown an Avro Avian from South Africa to England. She took a fancy to the Avian and asked George Putnam to buy it and have it shipped to America. They all sailed home on the SS Roosevelt.

Putnam’s organisation had been working hard. All of New York seemed to have congregated to greet Amelia - spraying fireboats, playing bands and the ultimate acknowledgement of fame, a ticker tape parade. Three days in New York, two days in Boston, Williamsburg, Chicago, Toledo . . . Amelia had leapt from weekend club flyer to international heroine just for being, as she put it, ‘no better than a sack of potatoes’.

When the flood of requests for appearances receded Amelia worked on her book which was based on the log and notes she had made during the flight. Putnam then arranged for her to fly the Avian to the West coast, like a holiday trip but really to show the public that she was an aviator in her own right, with her own aeroplane. Every stop involved some kind of a civic welcome and a speech from Amelia. She didn’t like speaking in public. She needed 15 minutes alone to compose herself beforehand. When she did take the stage she spoke well and audiences found her interesting, friendly and modest.

When she got back she was asked to be ‘Aviation Editor’ (which meant a monthly column) of Cosmopolitan, a fashion magazine. More earnings came from product sponsorship. She took part in the first Women’s Air Derby and led the protest against the ‘easier’ course which had been set for the women. It was changed so that they flew the same course as the men. Using a Lockheed Vega she flew in the race and went on to set a number of point-to point speed records. She was one of the founders of the Ninety-Nines, the group for women aviators. What became almost her ‘day job’ was promoting two small newly formed air lines, not easy in the depressed economy at the time.

A major change in her life style came after George Putnam and his wife divorced. George asked her to marry him. Her instinctive reaction was to say ‘no’. She had always seen marriage as the principal example of the subjugation of women. Hadn’t it ruined the career of Neta, her first instructor?

However, she and George were so closely involved – he had ‘discovered’ her and now managed her - that it seemed that marriage might even help in their activities. She kept George at bay for two years. In the end, she drew up a pre-nuptial contract to make sure that they would live ‘parallel’ lives and that she would be released if she couldn’t stand marriage. The wedding was in a small private ceremony on 7th February 1931.

Less than a year later, Amelia told G.P. that she was going to fly the Atlantic. A second hand Lockheed Vega was quietly bought and prepared by Bernt Balchen, the Polar aviator. When the weather seemed favourable, Balchen, with Amelia in the cabin, flew the Vega to Harbor Grace in Newfoundland. On 20th May, 1932, the fifth anniversary of Lindbergh’s take-off, Amelia left Harbor Grace. As darkness fell she ran into a severe storm. The rev. counter failed and her altimeter wasn’t working. The Vega began to pick up ice and dropped into a spin. She recovered in sight of the waves. Then the exhaust manifold split and the blare of light destroyed her night vision. Somehow, she recovered and got back on course, eventually finding Ireland and landing near Londonderry after 14 hrs 56 mins in the air.

When she got back she was asked to be ‘Aviation Editor’ (which meant a monthly column) of Cosmopolitan, a fashion magazine. More earnings came from product sponsorship. She took part in the first Women’s Air Derby and led the protest against the ‘easier’ course which had been set for the women. It was changed so that they flew the same course as the men. Using a Lockheed Vega she flew in the race and went on to set a number of point-to point speed records. She was one of the founders of the Ninety-Nines, the group for women aviators. What became almost her ‘day job’ was promoting two small newly formed air lines, not easy in the depressed economy at the time.

A major change in her life style came after George Putnam and his wife divorced. George asked her to marry him. Her instinctive reaction was to say ‘no’. She had always seen marriage as the principal example of the subjugation of women. Hadn’t it ruined the career of Neta, her first instructor?

However, she and George were so closely involved – he had ‘discovered’ her and now managed her - that it seemed that marriage might even help in their activities. She kept George at bay for two years. In the end, she drew up a pre-nuptial contract to make sure that they would live ‘parallel’ lives and that she would be released if she couldn’t stand marriage. The wedding was in a small private ceremony on 7th February 1931.

Less than a year later, Amelia told G.P. that she was going to fly the Atlantic. A second hand Lockheed Vega was quietly bought and prepared by Bernt Balchen, the Polar aviator. When the weather seemed favourable, Balchen, with Amelia in the cabin, flew the Vega to Harbor Grace in Newfoundland. On 20th May, 1932, the fifth anniversary of Lindbergh’s take-off, Amelia left Harbor Grace. As darkness fell she ran into a severe storm. The rev. counter failed and her altimeter wasn’t working. The Vega began to pick up ice and dropped into a spin. She recovered in sight of the waves. Then the exhaust manifold split and the blare of light destroyed her night vision. Somehow, she recovered and got back on course, eventually finding Ireland and landing near Londonderry after 14 hrs 56 mins in the air.

Then it was on to London to an overwhelming welcome – dance with the Prince of Wales – and Paris – Legion d’Honneur.

In New York –a ticker tape parade – the President presented the National Geographic Society’s gold medal and Congress awarded her the DFC. However, the real reward of the flight for Amelia was that she felt she had finally justified her fame and buried the ‘sack of potatoes’.

In August she became the first woman to fly coast to coast (2447.8 miles in 19hrs 5 mins). In July 1933 she did it again, cutting the record to 17hrs 7 mins.

In New York –a ticker tape parade – the President presented the National Geographic Society’s gold medal and Congress awarded her the DFC. However, the real reward of the flight for Amelia was that she felt she had finally justified her fame and buried the ‘sack of potatoes’.

In August she became the first woman to fly coast to coast (2447.8 miles in 19hrs 5 mins). In July 1933 she did it again, cutting the record to 17hrs 7 mins.

Christmas 1934 was spent in Hawaii. Amelia and G. P. had travelled there by sea, shipping also a Lockheed Vega ’just to fly round the islands’ said Amelia. But speculation that she intended to fly back to the US was rife and many voices were raised against any such flight. Just three weeks earlier Charles Ulm, who had flown with Kingsford Smith on the first flight across the Pacific in 1928, had left Hawaii with two companions on the way to Australia and they had disappeared. The disastrous Dole Derby in 1927, when ten flyers were lost was still in the memory and too many other fliers trying to reach the mainland had died.

On 11 January 1935, saying something about a ‘test take off’, Amelia left from a muddy Wheeler Field, heading for California. The expected struggle through bad weather without blind flying instruments was aggravated by the loss of a cover from a ventilation duct. A steady stream of cold air blew directly into one eye. Even though the target was a broad one Amelia had no means of checking her navigation and throttled back to save fuel. Two hours behind her schedule she landed in Oakland, desperately tired. There was a plan to ‘link the capitals’ and fly on to Washington but snowstorms over the mountains saved her the effort. Being the first person to make the flight from Hawaii solo was enough.

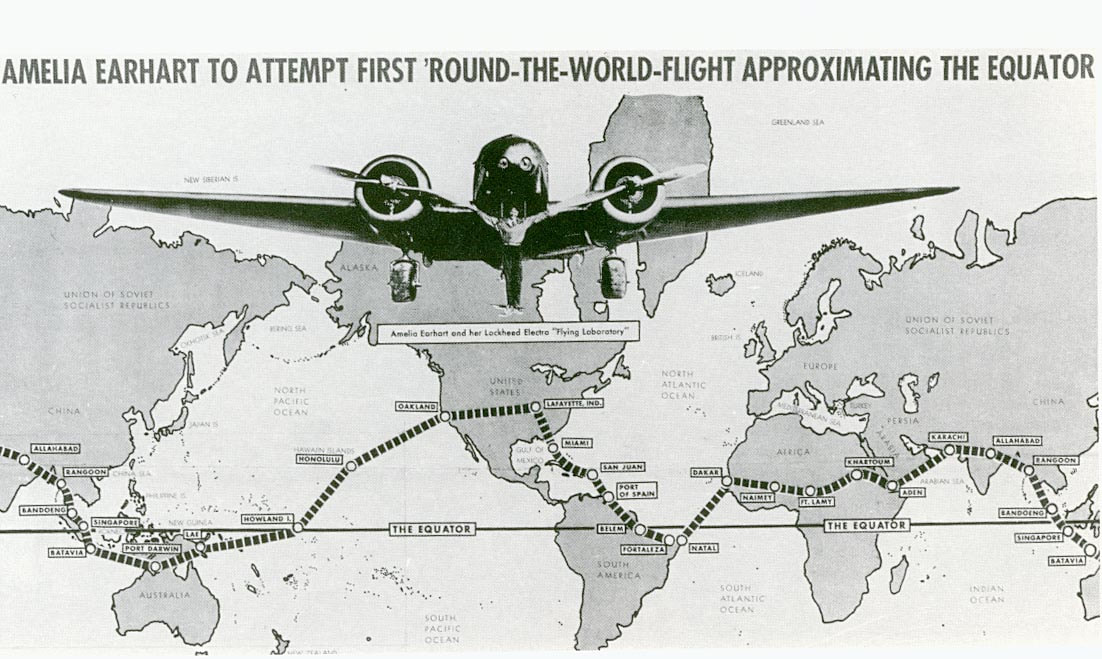

Even more in demand for talks – she was on stage 135 times in 1935 - Amelia found time to fit in record flights from Los Angeles to Mexico City and Mexico City to Newark. Early in 1936 she told Putnam that she had set her sights on flying round the world at the equator. No woman, or man, had done this.

Putnam went into top gear. The main requirement was money. Amelia had been appointed ‘Students’ Career Counsellor’ at Purdue University in Indiana. Unusual for a university it had a School of Aeronautics which majored on research. G.P. persuaded Purdue to set up a special research fund which could contribute to the purchase of an aeroplane. That made $50,000 available. Other donors gave their money freely and Putnam turned to more difficult matters.

On previous flights Amelia hadn’t bothered with flight permits. On one of her Mexico flights she had entered the US illegally and was threatened with a $500 fine, later waived. G.P wrote to the Department of Commerce for the permissions for the world flight. Also Amelia’s transport licence needed to be renewed and she needed an instrument rating. He contacted the Navy to provide refuelling facilities at Midway Island. To grease the wheels he wrote to Eleanor Roosevelt, the President’s wife. She had formed a firm friendship with Amelia and her knowledge of Putnam's requests to various Government departments would spur positive action.

The Navy’s response even reached the President himself. He wrote ‘Do what we can for Mrs. Putnam’. The Navy ruled out the use of Midway and offered the use of Howland Island. This uninhabited speck in the Pacific was two miles long and half a mile wide. It stood no more than 20 feet above sea level. Building an airstrip there would not be difficult and could be justified as another brick in the defensive wall being built to counter Japanese military expansion in the Pacific. The Navy would do that, provided Putnam paid the wages of four of the twelve labourers who would do the work. Offered with no charge was the stationing of a Coastguard Cutter near the island to provide radio communication and Direction Finding.

On 11 January 1935, saying something about a ‘test take off’, Amelia left from a muddy Wheeler Field, heading for California. The expected struggle through bad weather without blind flying instruments was aggravated by the loss of a cover from a ventilation duct. A steady stream of cold air blew directly into one eye. Even though the target was a broad one Amelia had no means of checking her navigation and throttled back to save fuel. Two hours behind her schedule she landed in Oakland, desperately tired. There was a plan to ‘link the capitals’ and fly on to Washington but snowstorms over the mountains saved her the effort. Being the first person to make the flight from Hawaii solo was enough.

Even more in demand for talks – she was on stage 135 times in 1935 - Amelia found time to fit in record flights from Los Angeles to Mexico City and Mexico City to Newark. Early in 1936 she told Putnam that she had set her sights on flying round the world at the equator. No woman, or man, had done this.

Putnam went into top gear. The main requirement was money. Amelia had been appointed ‘Students’ Career Counsellor’ at Purdue University in Indiana. Unusual for a university it had a School of Aeronautics which majored on research. G.P. persuaded Purdue to set up a special research fund which could contribute to the purchase of an aeroplane. That made $50,000 available. Other donors gave their money freely and Putnam turned to more difficult matters.

On previous flights Amelia hadn’t bothered with flight permits. On one of her Mexico flights she had entered the US illegally and was threatened with a $500 fine, later waived. G.P wrote to the Department of Commerce for the permissions for the world flight. Also Amelia’s transport licence needed to be renewed and she needed an instrument rating. He contacted the Navy to provide refuelling facilities at Midway Island. To grease the wheels he wrote to Eleanor Roosevelt, the President’s wife. She had formed a firm friendship with Amelia and her knowledge of Putnam's requests to various Government departments would spur positive action.

The Navy’s response even reached the President himself. He wrote ‘Do what we can for Mrs. Putnam’. The Navy ruled out the use of Midway and offered the use of Howland Island. This uninhabited speck in the Pacific was two miles long and half a mile wide. It stood no more than 20 feet above sea level. Building an airstrip there would not be difficult and could be justified as another brick in the defensive wall being built to counter Japanese military expansion in the Pacific. The Navy would do that, provided Putnam paid the wages of four of the twelve labourers who would do the work. Offered with no charge was the stationing of a Coastguard Cutter near the island to provide radio communication and Direction Finding.

On 20 March, 1936, Amelia took delivery of her new aeroplane. Paul Mantz, who had worked with Amelia and Putnam on other projects, drew up a list of essential equipment to be fitted to the Electra. Extra fuel tanks, of course, also a Sperry autopilot, hatch for navigator’s sighting, comprehensive radio, etc., etc. . Mantz was shocked when Putnam routinely rejected expensive equipment and wanted to settle for cheap or inferior gear. He seemed to have no concern for Amelia’s safety.

Amelia began learning to fly the Electra with Paul Mantz. She was not a good student. Mantz called himself a ‘precision pilot’. He had to be to deliver the unusual manoeuvres and stunts demanded by the film industry. He was annoyed by Amelia’s casual attitude and willingness to be distracted. He struggled to make her understand how to use the throttles to prevent swing on take-off. She also had some lessons with Kelly Johnson, the Electra’s designer. He was less critical of Amelia’s flying; he was concentrating on the use of the Cambridge analyser which helped to control the fuel supply and mixture to achieve maximum range.

Amelia began learning to fly the Electra with Paul Mantz. She was not a good student. Mantz called himself a ‘precision pilot’. He had to be to deliver the unusual manoeuvres and stunts demanded by the film industry. He was annoyed by Amelia’s casual attitude and willingness to be distracted. He struggled to make her understand how to use the throttles to prevent swing on take-off. She also had some lessons with Kelly Johnson, the Electra’s designer. He was less critical of Amelia’s flying; he was concentrating on the use of the Cambridge analyser which helped to control the fuel supply and mixture to achieve maximum range.

Fred Noonan

Fred Noonan

Inevitably, the round the world plan became common knowledge. The route planned was west across the Pacific to Australia for which Amelia would need a navigator. Then she thought she could carry on alone and rely on map and compass for the rest of the trip. The first choice as navigator seemed to be Harry Manning. He had been captain of the liner which brought Amelia home from her first Atlantic flight in 1928. He might have coped with ships but had no experience of navigating aeroplanes.

Four days before take-off, G.P found a back-up. Fred Noonan had experience of navigating Pan American’s Clipper Ships across the Pacific – until he was fired for alcoholism. Amelia was not keen – she remembered Stultz. Noonan assured her that he had conquered his addiction. Amelia didn’t want to hurt Manning so she said she’d take ‘two hitchhikers’ as far as Honolulu - Noonan and Mantz. Also on board were 6,500 First Day Covers, envelopes to be signed by Amelia. Putnam planned to sell them after the flight to re-coup some of his expenses.

Four days before take-off, G.P found a back-up. Fred Noonan had experience of navigating Pan American’s Clipper Ships across the Pacific – until he was fired for alcoholism. Amelia was not keen – she remembered Stultz. Noonan assured her that he had conquered his addiction. Amelia didn’t want to hurt Manning so she said she’d take ‘two hitchhikers’ as far as Honolulu - Noonan and Mantz. Also on board were 6,500 First Day Covers, envelopes to be signed by Amelia. Putnam planned to sell them after the flight to re-coup some of his expenses.

At Oakland on 17 March, 1937 Amelia sat in the co-pilot’s seat for the take-off. She would fly whilst Mantz, who had agreed to fly on this first leg only, sat in the left hand seat and would handle the throttles. He took the opportunity to reinforce his training. ‘Never jockey the throttles’, he said. ‘Use the rudder and don’t raise the tail too soon’. During the flight, Amelia flew for fifty minutes of every hour. Mantz thought she was unusually tired and easily irritated by Manning’s frequent appearances in the cockpit to take star sights or adjust the radio controls. When they reached Wheeler Field she asked Mantz to do the landing.

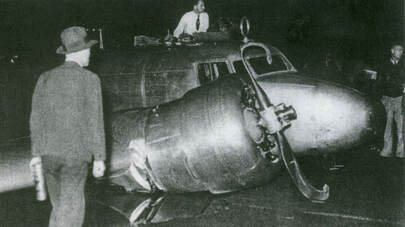

Take-off was planned for later that night after a few hours sleep but bad weather intervened. Noonan got drunk. It wasn’t till 20th March that they were able to leave in the early morning darkness. Speeding across the wet field, the Electra began to swing. A wing dropped, the right undercarriage leg collapsed and the Electra ground looped. There was a brief flash of flame but no more fire. Amelia, Manning and Noonan climbed out unhurt. ‘I think I hit a wet spot – a tyre blew out’ thought Amelia.

The reason for accident was not fully established though Mantz, who had watched it from the ground, was not in doubt. Amelia made arrangements to leave for California on a ship sailing at noon leaving the Army furious that they were expected to clear $100,000 worth of wreckage from their airfield. She also failed to report the accident – another $500 penalty. The Bureau of Commerce in Hawaii decided not to levy the fine. In the aftermath Putnam managed to offend almost everyone before having to pay expensive contractors to have the Electra shipped home.

Take-off was planned for later that night after a few hours sleep but bad weather intervened. Noonan got drunk. It wasn’t till 20th March that they were able to leave in the early morning darkness. Speeding across the wet field, the Electra began to swing. A wing dropped, the right undercarriage leg collapsed and the Electra ground looped. There was a brief flash of flame but no more fire. Amelia, Manning and Noonan climbed out unhurt. ‘I think I hit a wet spot – a tyre blew out’ thought Amelia.

The reason for accident was not fully established though Mantz, who had watched it from the ground, was not in doubt. Amelia made arrangements to leave for California on a ship sailing at noon leaving the Army furious that they were expected to clear $100,000 worth of wreckage from their airfield. She also failed to report the accident – another $500 penalty. The Bureau of Commerce in Hawaii decided not to levy the fine. In the aftermath Putnam managed to offend almost everyone before having to pay expensive contractors to have the Electra shipped home.

Back in California, Amelia agonised about trying again. She faced a storm of criticism in some newspapers, balanced by a wave of sympathetic support from her many friends. G.P. renewed his drive to raise more funds. $25,000 was needed for repairs to the Electra and another $25,000 for a new set of permissions and licences. The pattern of climate was changing and it would be better to make the flight eastbound. Manning had to go back to his sea job but Noonan was still available. Amelia didn’t want him but he was a good navigator and cheap.

The Electra was repaired with a few minor modifications. A navigator’s sighting hatch was fitted in the rear fuselage where Noonan would sit. They tested an inter-com system but Amelia couldn’t hear it above the noise of the engines so they settled for a fishpole hung in the fuselage above Amelia’s right shoulder which reached back to Noonan. Clothes pegs were used to hold hand written notes. Various radios were available. The best for direction finding was a 500 kcs marine radio which required a 250 ft trailing aerial. Amelia didn’t like that and it was quietly left behind. In any case, neither she nor Noonan could use Morse code. She would use only voice transmissions on 6,210 Hz by day and 3,105 Hz by night.

In the early morning of 1st June, 1937 the Electra left the runway at Miami and they crossed the Caribbean and coasted down to Natal in Brazil, averaging 4-5 hours sleep at nights. Noonan’s navigation was accurate and the plane was behaving although Amelia frequently suffered bouts of nausea from petrol fumes. They crossed the Atlantic, had minor diversions to avoid bad weather in Africa and, after two weeks, had reach Eritrea, just past the half-way point.

In Karachi she spent two days supervising the stamping of 7,500 covers and enjoying a camel ride. Her fuel analyser had broken and G.P. arranged for a KLM engineer to fix it when she reached Singapore. From Calcutta she reported that she was having ‘personal troubles’, interpreted that Noonan was drinking again. Monsoon rains over the Bay of Bengal caused the Electra to turn back twice.

At the end of the third week, she reached Bandung in Indonesia. It was a clear day, yet she circled the field for fifteen minutes before landing. She said she couldn’t see the aerodrome markers. Observers were concerned that she was suffering from accumulated fatigue. Three days were spent in Bandung, during which the KLM engineers worked on the fuel analyser and ‘other instruments’ that were giving trouble.

They reached Lae in New Guinea with the toughest leg ahead. Before the 2,556 mile flight they did their final checks. Amelia offloaded anything she thought unnecessary to reduce weight and increase range. She even threw out the survival equipment. She and Noonan went to different farewell parties and it was noticed that Noonan drank very little.

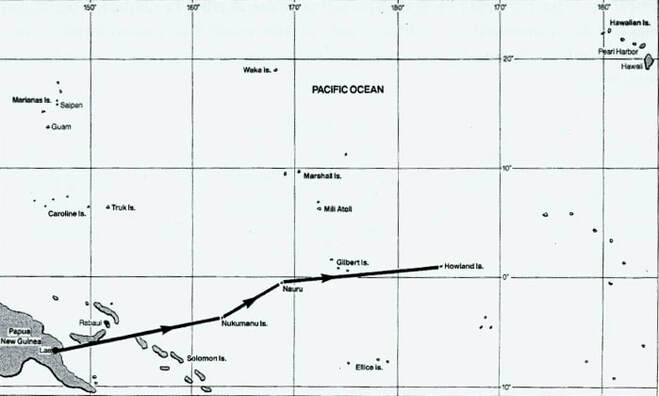

At 1022 on 2nd July the Electra became airborne just 50 yds before the end of the 1,000 ft dirt runway in ‘a hair-raising take-off’. A radioman of New Guinea Airways kept in touch with Amelia for the next seven hours until her signals faded.

At this point, the management of the flight was in the hands of three people – Putnam, who was autocratic and impulsive and often not well informed, Richard Black of the Department of Commerce who was on the Coastguard Cutter Itasca as Putnam’s representative, but always conscious of his department’s interests and finally, Captain W K Thompson of the Itasca who resented being dispatched to the far Pacific to provide services to a civilian. As well as Black, he had to take along a USAAC observer, Lt Cooper and two reporters.

Black and Cooper had borrowed an experimental D/F set from the Navy to set up on Howland and wanted to bring several Navy radiomen. Thompson said it was inadequate and he could not officially accept it but he allowed one extra radioman from the Coastguard technician to come aboard. Putnam told Black about the Electra’s radio frequencies and added that her D/F operated from 200 to 1400 kcs. Nobody realised that Amelia had left the key and aerial in Miami and was relying entirely on voice transmissions made every half hour on 6,210 Hz and 3,105 Hz, neither of which could be used by Itasca’s D/F equipment.

The Electra was repaired with a few minor modifications. A navigator’s sighting hatch was fitted in the rear fuselage where Noonan would sit. They tested an inter-com system but Amelia couldn’t hear it above the noise of the engines so they settled for a fishpole hung in the fuselage above Amelia’s right shoulder which reached back to Noonan. Clothes pegs were used to hold hand written notes. Various radios were available. The best for direction finding was a 500 kcs marine radio which required a 250 ft trailing aerial. Amelia didn’t like that and it was quietly left behind. In any case, neither she nor Noonan could use Morse code. She would use only voice transmissions on 6,210 Hz by day and 3,105 Hz by night.

In the early morning of 1st June, 1937 the Electra left the runway at Miami and they crossed the Caribbean and coasted down to Natal in Brazil, averaging 4-5 hours sleep at nights. Noonan’s navigation was accurate and the plane was behaving although Amelia frequently suffered bouts of nausea from petrol fumes. They crossed the Atlantic, had minor diversions to avoid bad weather in Africa and, after two weeks, had reach Eritrea, just past the half-way point.

In Karachi she spent two days supervising the stamping of 7,500 covers and enjoying a camel ride. Her fuel analyser had broken and G.P. arranged for a KLM engineer to fix it when she reached Singapore. From Calcutta she reported that she was having ‘personal troubles’, interpreted that Noonan was drinking again. Monsoon rains over the Bay of Bengal caused the Electra to turn back twice.

At the end of the third week, she reached Bandung in Indonesia. It was a clear day, yet she circled the field for fifteen minutes before landing. She said she couldn’t see the aerodrome markers. Observers were concerned that she was suffering from accumulated fatigue. Three days were spent in Bandung, during which the KLM engineers worked on the fuel analyser and ‘other instruments’ that were giving trouble.

They reached Lae in New Guinea with the toughest leg ahead. Before the 2,556 mile flight they did their final checks. Amelia offloaded anything she thought unnecessary to reduce weight and increase range. She even threw out the survival equipment. She and Noonan went to different farewell parties and it was noticed that Noonan drank very little.

At 1022 on 2nd July the Electra became airborne just 50 yds before the end of the 1,000 ft dirt runway in ‘a hair-raising take-off’. A radioman of New Guinea Airways kept in touch with Amelia for the next seven hours until her signals faded.

At this point, the management of the flight was in the hands of three people – Putnam, who was autocratic and impulsive and often not well informed, Richard Black of the Department of Commerce who was on the Coastguard Cutter Itasca as Putnam’s representative, but always conscious of his department’s interests and finally, Captain W K Thompson of the Itasca who resented being dispatched to the far Pacific to provide services to a civilian. As well as Black, he had to take along a USAAC observer, Lt Cooper and two reporters.

Black and Cooper had borrowed an experimental D/F set from the Navy to set up on Howland and wanted to bring several Navy radiomen. Thompson said it was inadequate and he could not officially accept it but he allowed one extra radioman from the Coastguard technician to come aboard. Putnam told Black about the Electra’s radio frequencies and added that her D/F operated from 200 to 1400 kcs. Nobody realised that Amelia had left the key and aerial in Miami and was relying entirely on voice transmissions made every half hour on 6,210 Hz and 3,105 Hz, neither of which could be used by Itasca’s D/F equipment.

The first part of the flight was in daylight and it’s very likely that Noonan used the larger islands on the route to check his position. After dark, he would use his sextant to take sightings on stars, a method which could establish a position to within three miles. The radio operator on Nauru picked up a radio message from Amelia though the static was too bad to decipher what was said. (A US ship well south of Nauru heard nothing). The timing of this message indicated that Amelia was behind schedule, obviously meeting headwinds stronger than forecast.

At 1744 GMT (sunrise at Howland but not yet at the Electra) the Itasca operators heard Amelia call ‘. . .bearing on 3105 . . . will whistle in mike . . .’. A minute later she said ‘About 200 miles out . .whistling . . . ‘. The whistling was hard to hear and not long enough to take a bearing. At 1815 she asked for another bearing, saying she was 100 miles out. They couldn’t have flown 100 miles in the 30 minutes since the previous call and it is probable that Noonan had recalculated their position by noting the precise time of the sunrise flash.

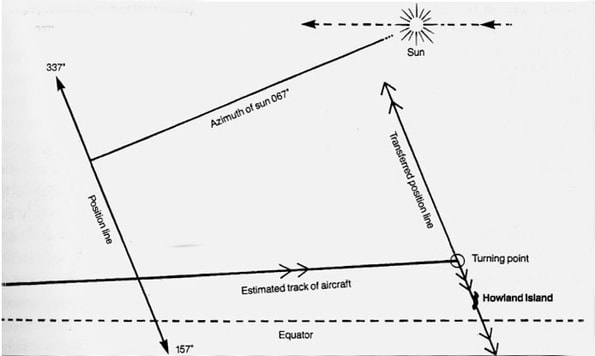

At 1915 ‘Gas is running low. . Been unable to reach you by radio. . . Flying at 1000 ft’. At 2014, Amelia sent her last message. ‘We are on a line of position 157 to 337. We are running north and south’. The heavy cloud build up that was forcing her down to 1000 ft could be seen from Itasca. The message was loud and clear but the Electra could not be seen. Nothing further was heard. Amelia, Noonan and the Electra had disappeared.

The search involved 4000 men, ten ships and 65 planes which scanned sea and islands. It went on for sixteen days until called off – by the Navy, at least. Almost immediately, a new search began based purely on speculation. It reached such lengths that the President had to make an official statement that Amelia had not been on a secret mission for the Government. It still smoulders on today.

That last message from Amelia has triggered many lines of enquiry. Why was she flying north and south instead of heading east? Well, Noonan had been a ship’s navigator and must have used a mariner’s technique when approaching a destination. He had plotted the distance to go and drawn a line on the chart at right angles to his course. Then when he reached the line, he knew that his destination was either north or south. How did he get Amelia to understand this from notes on scraps of paper?

At 1744 GMT (sunrise at Howland but not yet at the Electra) the Itasca operators heard Amelia call ‘. . .bearing on 3105 . . . will whistle in mike . . .’. A minute later she said ‘About 200 miles out . .whistling . . . ‘. The whistling was hard to hear and not long enough to take a bearing. At 1815 she asked for another bearing, saying she was 100 miles out. They couldn’t have flown 100 miles in the 30 minutes since the previous call and it is probable that Noonan had recalculated their position by noting the precise time of the sunrise flash.

At 1915 ‘Gas is running low. . Been unable to reach you by radio. . . Flying at 1000 ft’. At 2014, Amelia sent her last message. ‘We are on a line of position 157 to 337. We are running north and south’. The heavy cloud build up that was forcing her down to 1000 ft could be seen from Itasca. The message was loud and clear but the Electra could not be seen. Nothing further was heard. Amelia, Noonan and the Electra had disappeared.

The search involved 4000 men, ten ships and 65 planes which scanned sea and islands. It went on for sixteen days until called off – by the Navy, at least. Almost immediately, a new search began based purely on speculation. It reached such lengths that the President had to make an official statement that Amelia had not been on a secret mission for the Government. It still smoulders on today.

That last message from Amelia has triggered many lines of enquiry. Why was she flying north and south instead of heading east? Well, Noonan had been a ship’s navigator and must have used a mariner’s technique when approaching a destination. He had plotted the distance to go and drawn a line on the chart at right angles to his course. Then when he reached the line, he knew that his destination was either north or south. How did he get Amelia to understand this from notes on scraps of paper?

Why did they not deliberately aim to one side of the island so that they knew which way to turn, as Francis Chichester had done when he hopped from New Zealand to Australia via two small islands?

Did Noonan make the correct adjustment for his height when he timed sunrise? At 1000 ft it is 31 miles, at 2000 ft 44 miles, at 3000ft 70 miles.

And another thing, why . . . ?