1924 Two Seater Aeroplane Competition (Oct 2020)

The air of optimism for the advancement of aviation which pervaded the Royal Aero Club and the Air Ministry was still present in 1924. The competitions of the previous two years had produced no positive result yet the format was still attractive and seemed worth repeating. This time it would be for practical two-seater aeroplanes, a much better goal. And all aeroplanes and engines would have to be British – no foreign competition allowed. (Well, didn’t the French have a similar rule for their competition?). First prize would be £2000 with £1000 for second. Other prizes would reward take off and landing performance, reliability and most laps flown throughout the competition. There were the usual requirements for two men to dismantle, or fold their aeroplane, move 100 metres through a 2.5 metre gap and re-assemble and fly it within one hour.

Perversely, the designers of these ‘practical’ craft would still be hampered by a restriction on the size of the engines which could be used, a maximum of 1100 cc and weighing no more than 170 lbs. This, despite the fact that there was no suitable British engine near this size either in production or on the drawing board. In the event, modified Bristol Cherub and Douglas twin motor cycle engines powered most of the competitors who gathered at Lympne at the end of September.

Perversely, the designers of these ‘practical’ craft would still be hampered by a restriction on the size of the engines which could be used, a maximum of 1100 cc and weighing no more than 170 lbs. This, despite the fact that there was no suitable British engine near this size either in production or on the drawing board. In the event, modified Bristol Cherub and Douglas twin motor cycle engines powered most of the competitors who gathered at Lympne at the end of September.

Avro arrived with its elegant Avis. They entered the same aeroplane twice so that they could use two different engines – a Cherub driving a tiny ‘toothpick’ propeller or a Blackburne Thrush 3 cylinder radial (seen here).

Flown by the great Bert Hinckler there was continuous trouble with both engines and they figured nowhere in the results.

Another aeroplane entered twice was this Parnall Pixie, powered by the ubiquitous 32 hp Cherub.

Flown by the great Bert Hinckler there was continuous trouble with both engines and they figured nowhere in the results.

Another aeroplane entered twice was this Parnall Pixie, powered by the ubiquitous 32 hp Cherub.

Its double entry was to allow it to fly both as a monoplane and as a biplane.

A second Pixie, flown only as a biplane, used the Blackburne Thrush. Here it’s being piloted by Wg Cdr Sholto Douglas. This one finished 6th in the contest. The other Pixie dropped out on the third day.

A second Pixie, flown only as a biplane, used the Blackburne Thrush. Here it’s being piloted by Wg Cdr Sholto Douglas. This one finished 6th in the contest. The other Pixie dropped out on the third day.

The Short Satellite attracted much attention. Although the design didn’t start until the beginning of July – less than three months before the contest – the Short team’s entrant had an advanced light alloy monocoque fuselage. It was powered by a direct-drive 32 hp Cherub whose tiny prop spun at 4000 rpm. Later Cherubs had a geared drive whose larger slower turning props were much more efficient. The pilot, John Lankester Parker, test flew the Satellite but it just wasn’t capable of performing properly carrying both the pilot and a passenger.

R J Mitchell’s Supermarine Sparrow had ailerons on both wings which could be lowered as flaps. This feature proved to be useless because the increase in drag overpowered the little Cherub. Henry Biard (later of Schneider Trophy fame) tried hard – he had suffered 19 forced landings before the meeting. At Lympne it all came to naught when a conrod ventilated the crankcase.

Westland entered two aeroplanes. This is the Woodpigeon. It came in for some criticism from the judges for its ‘lack of aerodynamic refinement’. The thick interplane strut alongside the fuselage, needed for wing folding, disturbed the airflow and caused a lot of drag. Overweight and underpowered (Thrush engine) it fared badly in the strong winds which plagued the contest.

Westland’s second entry, the Thrush powered Widgeon, was a parasol monoplane designed by W E W ‘Teddy’ Petter. Its unusual wing planform reveal it to be some sort of ancestor of the Lysander. Sadly, it wasn’t allowed to show its capabilities. On the very first day it took off for its full-load trial. There was a turbulent gusty wind and as the Widgeon left the ground a down draught thrust one wing down. It touched the ground and the Widgeon cartwheeled into a heap of wreckage.

Later, it was rebuilt and a 60 hp Genet radial fitted. This transformed the Widgeon and with minor re-design it was put into production and 26 were bought by private owners.

Hawker’s Cygnet is familiar to us because of the two delightful replicas currently based at Old Warden.

Designed by W G Carter and Sydney Camm two were entered, one with an Anzani engine to be flown by Walter ‘Scruffy’ Longton who had won a prize with the E E Wren in the 1923 Competition.

The second had a Scorpion engine and was flown by Freddie Raynham, the first man to survive a spin back in 1911.

Designed by W G Carter and Sydney Camm two were entered, one with an Anzani engine to be flown by Walter ‘Scruffy’ Longton who had won a prize with the E E Wren in the 1923 Competition.

The second had a Scorpion engine and was flown by Freddie Raynham, the first man to survive a spin back in 1911.

Their performance was not outstanding but they came 3rd and 4th and Freddie Raynham won the £100 second prize for the best ‘Get-off and Pull-up’ (short take-off and landing runs). He also registered the slowest speed of controlled flight, 37.42 mph. Scruffy’s Cygnet – that’s the one in the picture above - went on flying, usually as the star of any show it attended right up to 1972, when it retired gracefully to Cosford.

Second place in the competition went to the Bristol Brownie. (The name came from the Girl Guides’ Junior Brigade and it’s conceivable that there must have been a link somewhere back to the Bristol Scout). Designed by Frank Barnwell, from whose drawing board came the Bristol F2.B Fighter, the Brownie was a thoroughly workmanlike machine with a steel tube fuselage. Its pilot, Cyril Uwins had the luxury of choice of no fewer than four sets of wings – two of wood, one of metal and one composite. Inevitably, it was powered by a Cherub (the better version of course, with the geared drive) which didn’t dare misbehave since Bristol had made it themselves.

Second place in the competition went to the Bristol Brownie. (The name came from the Girl Guides’ Junior Brigade and it’s conceivable that there must have been a link somewhere back to the Bristol Scout). Designed by Frank Barnwell, from whose drawing board came the Bristol F2.B Fighter, the Brownie was a thoroughly workmanlike machine with a steel tube fuselage. Its pilot, Cyril Uwins had the luxury of choice of no fewer than four sets of wings – two of wood, one of metal and one composite. Inevitably, it was powered by a Cherub (the better version of course, with the geared drive) which didn’t dare misbehave since Bristol had made it themselves.

Bristol went home with the £1000 second prize, plus £500 for the best take-off and landing. Converted to a single seater, the Brownie had a successful career in air racing and soldiered on until 1928.

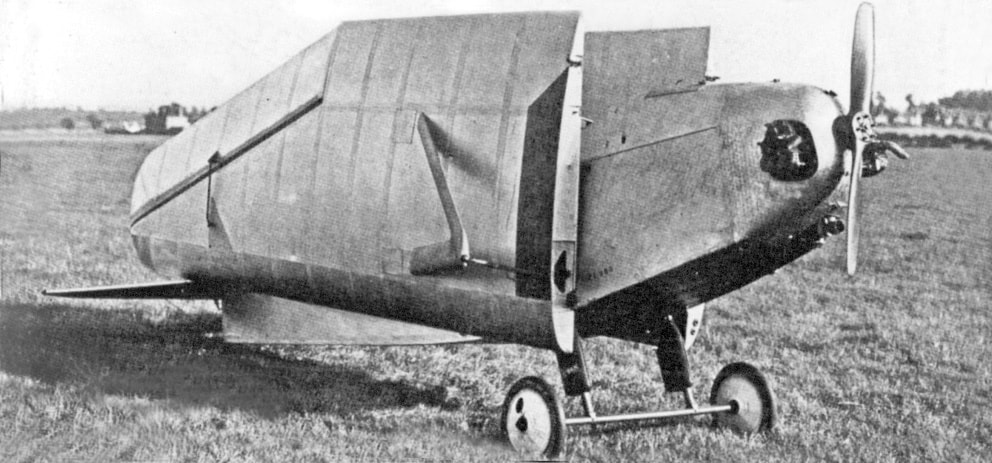

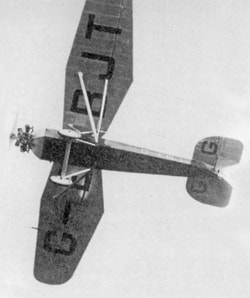

And who won the contest? The previous year the Air Navigation and Engineering Company had triumphed with their Anec I, designed by the talented Australian Bill Shackleton. They were back in 1924 with the slightly enlarged Anec II, the seat for the passenger fitted under the wing with access for awkward entry via a hatch in the wing’s upper surface.

And who won the contest? The previous year the Air Navigation and Engineering Company had triumphed with their Anec I, designed by the talented Australian Bill Shackleton. They were back in 1924 with the slightly enlarged Anec II, the seat for the passenger fitted under the wing with access for awkward entry via a hatch in the wing’s upper surface.

The judges were unimpressed. They thought the cramped cockpits were ‘quite inadequate for a person of average build’ and the ground clearance insufficient. The new Anzani engine had valve springs that were not suitable for normal operation and broke so often that the Anec was quickly eliminated from the contest.

Afterwards it was sold to a pilot who fitted a taller undercarriage and a better engine (a Cherub) and it performed quite well in an air race or two. It was registered G-EBJO and now sits in the Shuttleworth Collection.

Afterwards it was sold to a pilot who fitted a taller undercarriage and a better engine (a Cherub) and it performed quite well in an air race or two. It was registered G-EBJO and now sits in the Shuttleworth Collection.

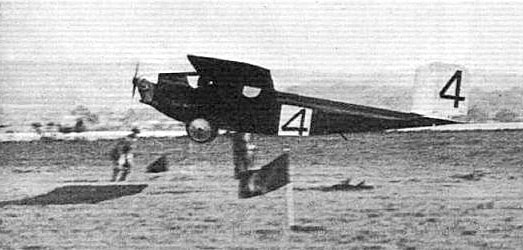

Before the competition Bill Shackleton had been hired by the Aviation Division of Beardmore, the giant Glasgow Engineering and Shipbuilding Company, specifically to take part in the contest at Lympne. It is hardly surprising that his design looked very like the Anec II, albeit with subtle differences. Although it was officially the Beardmore W.B. XXIV it was known by all as the Wee Bee. Like the Anec, it was criticised for its cramped cockpits even though the pilot, ahead of the wing had a much better view. Maurice Piercey kept his engine running to give a performance even better than the Brownie’s – 70.1 mph against 65.2 in the speed test. The Aeroplane magazine was fulsome in its praise. ‘The Wee Bee’, it said ‘was one of the most astonishingly efficient aeroplanes yet produced’.

Efficient it might have been but that was not sufficient to attract the attention of anyone looking for a touring aeroplane or a trainer to teach people to fly. Beardmore did not set up a production line and the sole Wee Bee appeared in a few races – and even was a class winner once. In 1933 it was sold to an Australian who seems to have enjoyed flying it until it suffered a crash in 1939. It was deemed to be not worthy of re-building.

A notable absentee from the Lympne trials was Geoffrey de Havilland. He had appeared in the 1922 Gliding Competition and at the 1923 contest his DH53 Humming Bird had made its mark. However, he had no interest in the two-seater contest because of its requirement to use ‘piddling little engines’. He knew that to get decent performance much more power was needed. Already in his factory he had a touring biplane, the DH51. That had been built to take advantage of the large number of cheap war-surplus engines available, notably the 90 hp RAF.1A V8 engine. (RAF is Royal Aircraft Factory). It had so much power that he was able to enlarge the passenger cockpit and fit in two seats. The DH 51 had already flown on 1st July 1924.

Inevitably, there was a problem. The RAF engine had a single ignition system and so could not gain a Certificate of Airworthiness. DH bought three of the engines which the Air Disposal Company had modified with a dual ignition system. They were fitted to the prototype and the two other DH51s which had been built. He now had three, potentially legal, efficient, expensive and unsaleable tourers.

(One was exported to Africa in 1926 and became the first Kenyan registered aircraft, another went to Australia in 1927 and the third appeared in various air races and events until 1933 when it was scrapped).

(One was exported to Africa in 1926 and became the first Kenyan registered aircraft, another went to Australia in 1927 and the third appeared in various air races and events until 1933 when it was scrapped).

Meanwhile the search for a suitable sensibly sized engine went on. De Havilland approached Frank Halford who had developed the Airdisco engine and persuaded him to design one half the size of the big V8. And that, effectively is what Halford did. He took four of the cylinders, pistons and gearing and designed a new crankshaft and crankcase. The result was the 60 hp Cirrus, the first 4-cylinder inline air cooled engine to go into production.

The DH 60 Moth emerged in 1925 and Geoffrey de Havilland himself carried out the first flight on 22nd February. Powered by the Cirrus engine the Moth set the standard for privately owned two seat tourers and club trainers.

The DH 60 Moth emerged in 1925 and Geoffrey de Havilland himself carried out the first flight on 22nd February. Powered by the Cirrus engine the Moth set the standard for privately owned two seat tourers and club trainers.

The Moth – and one or two others - established the format of ‘the peoples’ light aeroplane’. It’s evident that this was the principal aim of the Air Ministry and the Royal Aero Club in the first place when they organised their competitions. Unfortunately they introduced artificial restrictions and pointless goals which hindered rather than encouraged progress. In retrospect, observers and commentators concluded that Officialdom’s only achievement was that they had shown how not to do it.