Subaeronautical Tales (Aug 2014)

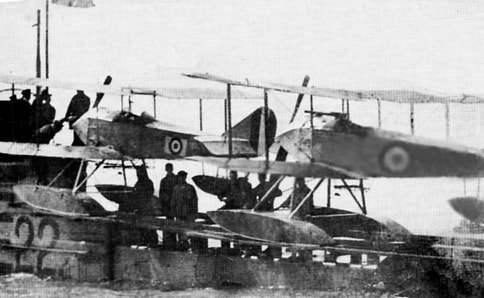

When the first World War began the German army put its Schlieffen plan into effect and attacked France via Belgium. The port of Zeebrugge was quickly overrun and provided a useful base for U-boats. The base commander was also a pilot and had two Friefrichshafen FF29 reconnaissance seaplanes available. He conceived the idea of extending the range of vision of his U-boats by using one of the seaplanes. In January, 1915, the little U-12 set sail into the wintry Channel with a bulky biplane lashed to its foredeck. Some thirty miles offshore, the sub’s forward tanks were flooded and the Friedrichshafen floated off. Despite the heavy swell, the take-off was successful and the plane flew along the Kent coast before returning to Zeebrugge. Recommendations to develop the practice of sub-aviation were firmly squashed by higher authority as impractical and the idea lay fallow until much later in the war.

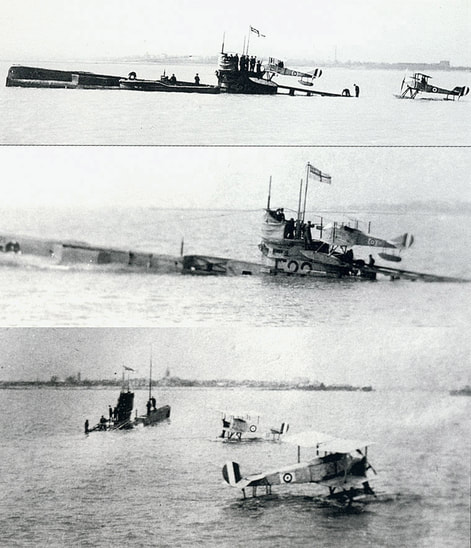

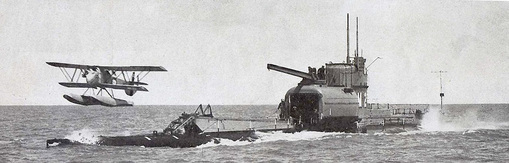

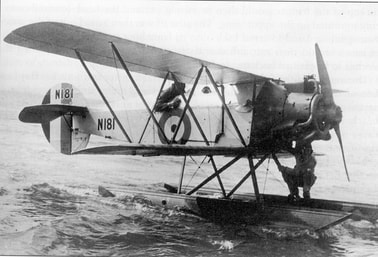

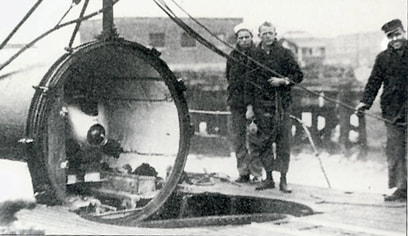

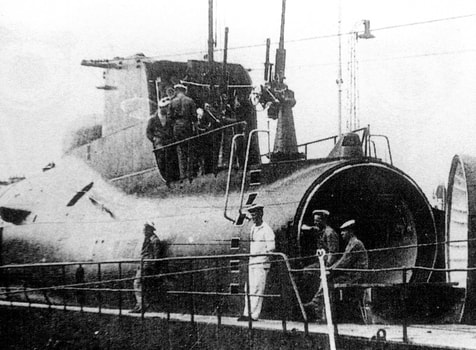

The idea of aeroplanes being launched by submarines survived the war and aircraft designers in several countries rose to the challenge of making a compact, easily erected seaplane. In 1920, the Royal Navy had launched the 1600 ton M-2 which was fitted with an enormous 12 inch gun. An international treaty agreed to limit submarine guns to 8 inches so the M-2’s gun was removed and replaced by a hangar. The seaplane which Parnall built to fit the hangar was named the Peto, after a former commander of the M-2. Its 28’ 5” wingspan folded to only 8 ft and the 135 hp Mongoose engine gave a top speed of 113 mph.

The launch sequence started whilst still submerged. The crew of 5 squeezed into the watertight hangar and electric heaters warmed the engine oil. On the surface, the lowered hangar door was part of the launching ramp and the Peto was pushed onto the ramp and the engine started. The aircrew climbed aboard as the wings were being unfolded and the sub turned into wind. With a 2.7g launch, the Peto was airborne in less than 40 ft. The time from surfacing to climb out was less than 5 minutes.

After alighting near the sub, a crane hoisted the Peto aboard. During the trials, the seaplane often flew back to its base and, on one occasion, a low-level run over a row of beach huts ended in disaster. A float caught the last hut in the row, completely destroying it. The Peto duly spread itself along the beach in a crumpled heap. The hut’s occupant, a prominent local doctor, stepped out of the wreckage and stomped to the Peto and began loudly abusing and cursing the, surprisingly unhurt, aircrew. They managed to stem the flow of abuse only when they pointed out to the doctor (and the gathering crowd) that he was completely naked. The ensuing outcry, whose echoes reached as far as the Admiralty, resulted in the replacement of the sub’s captain and also of both the aircrew. This was a particularly hard blow because they had been enjoying both flying pay and submariners’ pay.

Trials continued until 26 January, 1932 when the M-2 left Portland to join an exercise with other submarines. There was no further contact and the sub was presumed lost. When the wreck was finally found on the seabed of Portland Bay it was clear that the crew had been preparing to launch the Peto but the careful timing of blowing the ballast tanks and opening the hangar doors had gone wrong and the sub was flooded. The Admiralty abandoned all trials of using aircraft on submarines.

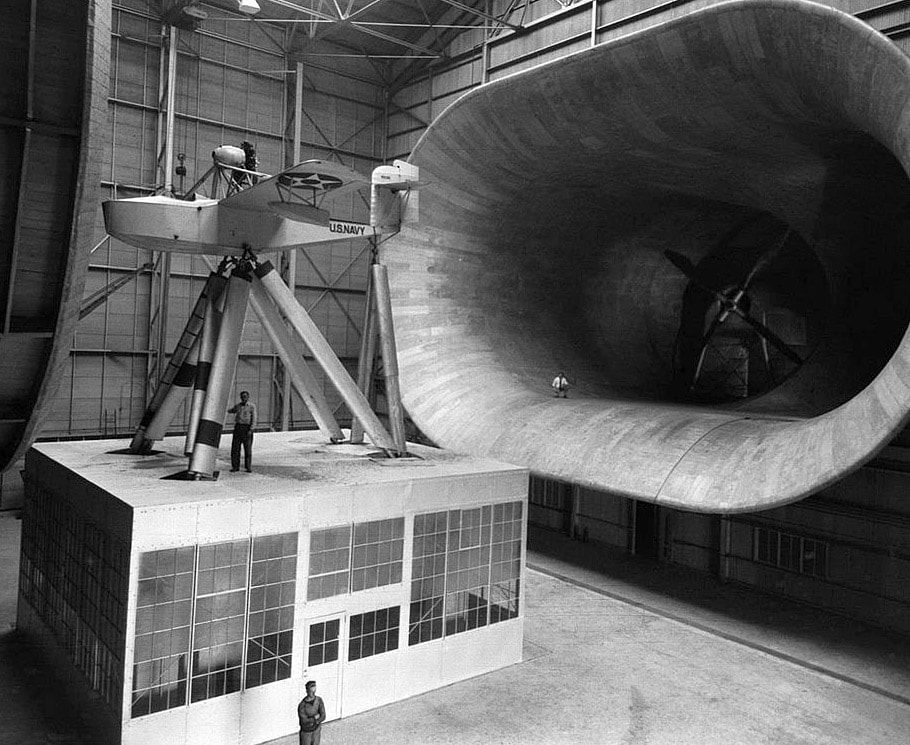

Elsewhere, the work went on apace. The USA produced a number of designs, the first being the compact Martin MS-1 to fit into USS S-1. This was soon followed by the Loening XSL-1 flying boat, which had the honour of being the first full size aircraft tested in the Navy’s new wind tunnel.

Trials continued until 26 January, 1932 when the M-2 left Portland to join an exercise with other submarines. There was no further contact and the sub was presumed lost. When the wreck was finally found on the seabed of Portland Bay it was clear that the crew had been preparing to launch the Peto but the careful timing of blowing the ballast tanks and opening the hangar doors had gone wrong and the sub was flooded. The Admiralty abandoned all trials of using aircraft on submarines.

Elsewhere, the work went on apace. The USA produced a number of designs, the first being the compact Martin MS-1 to fit into USS S-1. This was soon followed by the Loening XSL-1 flying boat, which had the honour of being the first full size aircraft tested in the Navy’s new wind tunnel.

The Loening successfully passed its flying tests but suffered from damage in an accident when being transported by road to The Anacostia River air base. Then the river overflowed its banks lifting the newly-repaired flying boat off its beaching trolley. It was found inverted and expensively damaged yet again. This was an unfortunate time for the news of the sinking of the Royal Navy’s M-2 to arrive. The Navy Board quietly lost interest in the whole project.

Italy tested fold-up seaplanes produced by Piaggio and Macchi which came to naught. The Soviet navy tried a small flying boat with such poor flight and water performance that it got nowhere near a submarine. Even Poland, tucked away in the Baltic, built an ocean-going sub which hangared a small flying boat which had performed well in trials. Both were destroyed in the German attack on Poland in 1939.

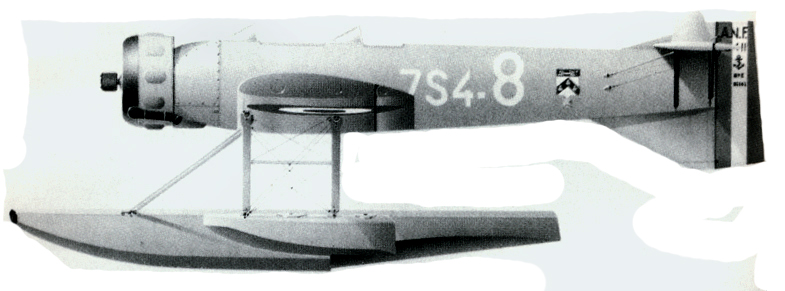

In 1934, the French navy proudly commissioned the Surcouf, a ‘commerce raider’. At over 4,000 tons it was the world’s largest submarine. Twin 8 in. guns were mounted ahead of the conning tower. Tucked in behind was a hangar which housed a Besson MB 411 observation floatplane.. In 1940 Surcouf was in poor repair in Cherbourg and escaped from the Germans by limping across the Channel to Plymouth. Most of the crew refused to join the Free French and were interned. The sub’s short chequered career ended when it was rammed at night by a freighter in the Caribbean. The Besson? There’s no record of its use. Whilst it was ashore for repairs in Plymouth it was destroyed by a passing air raid.

Italy tested fold-up seaplanes produced by Piaggio and Macchi which came to naught. The Soviet navy tried a small flying boat with such poor flight and water performance that it got nowhere near a submarine. Even Poland, tucked away in the Baltic, built an ocean-going sub which hangared a small flying boat which had performed well in trials. Both were destroyed in the German attack on Poland in 1939.

In 1934, the French navy proudly commissioned the Surcouf, a ‘commerce raider’. At over 4,000 tons it was the world’s largest submarine. Twin 8 in. guns were mounted ahead of the conning tower. Tucked in behind was a hangar which housed a Besson MB 411 observation floatplane.. In 1940 Surcouf was in poor repair in Cherbourg and escaped from the Germans by limping across the Channel to Plymouth. Most of the crew refused to join the Free French and were interned. The sub’s short chequered career ended when it was rammed at night by a freighter in the Caribbean. The Besson? There’s no record of its use. Whilst it was ashore for repairs in Plymouth it was destroyed by a passing air raid.

As the second World War approached a few countries seemed to be showing an interest in sub-borne aircraft but in Britain and the US the idea had long been abandoned. What about their future antagonists?

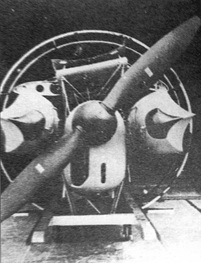

In Germany, it was as late as 1938 that the new Type XI class of boats were intended to have a U-bootsauge (U-boat’s eye). The Arado 231, a light seaplane with an endurance of four hours was produced. The centre section was angled so that its wings were set at slightly different heights and folded back one above the other. This masterpiece of assembly/breakdown could be completed in just four minutes. However, the flying characteristics of the Arado were very poor and take-off was impossible in anything more than lightly ruffled water. The whole project was quietly cancelled.

In Germany, it was as late as 1938 that the new Type XI class of boats were intended to have a U-bootsauge (U-boat’s eye). The Arado 231, a light seaplane with an endurance of four hours was produced. The centre section was angled so that its wings were set at slightly different heights and folded back one above the other. This masterpiece of assembly/breakdown could be completed in just four minutes. However, the flying characteristics of the Arado were very poor and take-off was impossible in anything more than lightly ruffled water. The whole project was quietly cancelled.

A simpler solution emerged. It might not have had the range of an aeroplane but it was a practical way to increase the sub’s range of vision. The Focke-Achgelis Fa 330 Bachstelze (Wagtail) rotor kite could be assembled from its small container and launched by winch regardless of the sea state. In one test it was climbing through 120 metres just 7 minutes after the sub surfaced. It was very easy to fly (pilot training was a few days in a wind tunnel in France) and needed only 18 knots of wind to stay airborne on tow behind the sub. It extended the conning tower’s visible horizon from 5 miles to 25 miles and reporting was instant via the telephone wire incorporated in the launching cable

Over 200 were built but they proved unpopular. Recovery was a very slow process, taking as long as 20 minutes. Surprisingly, with an operating height of just 500 ft, the pilot wore a parachute. In an ‘emergency’, he could jettison the rotor which, as it flew off, pulled out his parachute. He then released his straps allowing the body of the kite to fall away and giving him just enough time as he descended to enjoy a grandstand view of his sub disappearing beneath the waves. These kites were used only in the Indian Ocean – and Bachstelze wreckage was found there to prove it - by transport U-boats on their way to the Japanese bases in Malaya.

There were at least two other German projects using U-boats as launch vehicles. In 1942, Fritz Steinhoff, the captain of U-511, brought his boat into dock near Peenemunde. His brother was a rocket scientist and Fritz somehow got permission for them to experiment with launching rockets from his sub. The rockets were attached to the sides of the conning tower and waterproofed by wax. It worked – very well. Every launch was successful, even from a depth of 75 ft. Happily for the Allies, officialdom didn’t seem to notice and nothing came of the experiment.

There were at least two other German projects using U-boats as launch vehicles. In 1942, Fritz Steinhoff, the captain of U-511, brought his boat into dock near Peenemunde. His brother was a rocket scientist and Fritz somehow got permission for them to experiment with launching rockets from his sub. The rockets were attached to the sides of the conning tower and waterproofed by wax. It worked – very well. Every launch was successful, even from a depth of 75 ft. Happily for the Allies, officialdom didn’t seem to notice and nothing came of the experiment.

Operation Pelican, on the other hand, originated at the highest level. Two Junkers 87C dive bombers, the type modified for use by the Graf Zeppelin, Germany’s cancelled aircraft carrier, were further modified to be dismantled and stowed inside two Class VIIC long range U-boats. High-explosive bombs, two for each Stuka, were also taken aboard. In September 1943 all tests were completed and the boats made ready to sail to the Caribbean. The target was the earth dam which contains Gatun Lake. This lake is part of the Panama Canal and holds its main water supply. Breeching it would seriously disrupt the US sea supply network. After their catapult launch and attack the bombers would fly to a neutral country where the crews would sit out the war in internment. At the last minute the operation was called off because it was believed the plan had been leaked to the Americans.

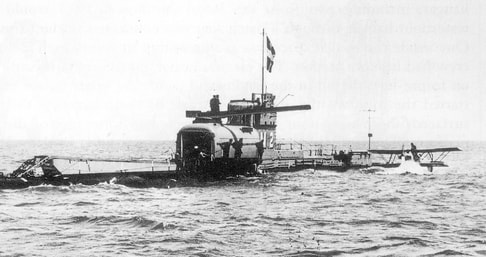

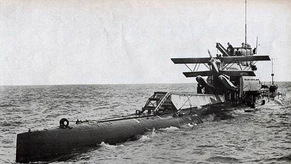

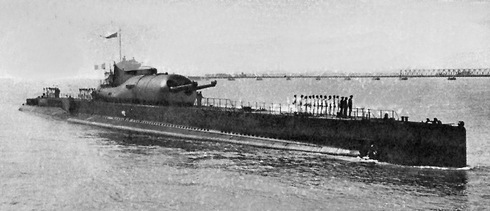

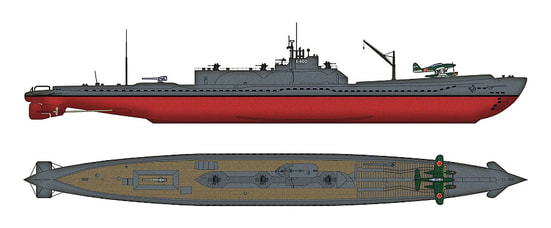

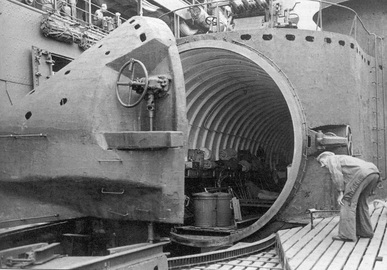

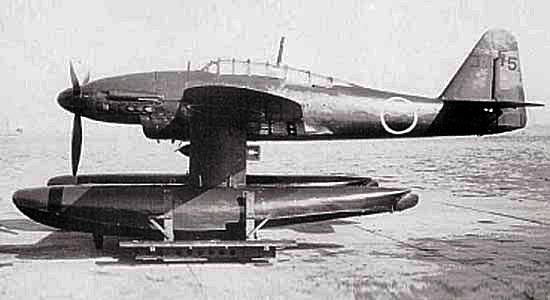

The U-boats which travelled to Malaya presented the Japanese with a couple of Bachstelze kites and were offered, in return, the Yokosuka E14Y1. These floatplanes were currently in service, carried on specially adapted subs, such as the I-15, seen here with its hangar forward of the conning tower

The Japanese, sitting as they were on the edge of the vast Pacific, had long been interested in extending the range of their submarines. As early as 1923, they began tests with a Heinkel seaplane. They also bought a Parnall Peto, surplus to the RN’s requirements after the M-2 sub sank in 1932. By December 1941 there were no fewer than 11 aircraft-carrying subs in service. Their first wartime operation was to provide the post Pearl Harbor attack photographs. Reconnaissance flights were flown over Sydney, Melbourne, New Zealand, the Aleutian Islands and Durban and Port Elizabeth in South Africa. After the Allies landed in Madagascar to take the island from the Vichy French a Yokosuka’s reconnaissance of the harbour allowed a midget submarine attack which sank a tanker and damaged the battleship HMS Ramilles.

|

Plans were formed to attack targets on the west coast of America, San Francisco, San Diego and – the Panama Canal, of course. These were watered down and changed to a fire attack on the forests of Oregon. On 9 September, 1942, W/O Nobuo Fujita launched from submarine I-25 and flew 50 miles inland to drop his two specially prepared bombs. He repeated the operation the next day. A third attack was cancelled because of rough seas. He made history by carrying out the first air raid on the mainland USA and undoubtedly caused fires but they were not as extensive as expected and made almost no impact on the course of the war.

|

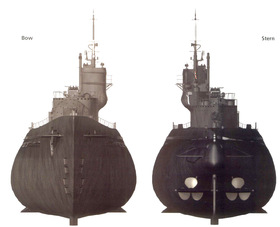

Spurred on by the desire to retaliate against the Doolittle raid in an equally spectacular way the Japanese decided to exploit the usefulness of aircraft-carrying subs by developing the giant I-400 class. These 400 ft long monsters had a displacement of 3,900 tons and a range of 37,500 miles. They carried three aircraft, the Aichi Sieran, powered by 1,400 hp engines and capable of carrying a torpedo or a 1,750 lb bomb.

Two were ready for service in July 1945 and, together with the smaller I-13 and I-14, each with two aircraft, set off to lead a 10–aircraft attack on the Gatun locks. The plan was to creep up the coast of South America to within striking distance of the Canal. After launch, the Sierans would jettison their floats to improve their performance and, on return to the subs, ditch the planes in the sea. However, soon after leaving Japan, the I-13 was detected and sunk. The remaining boats were diverted to attack the US carrier base in the Carolines but the war ended before they could go into action. When they surrendered the I-400s were a revelation to the Allies who studied them carefully. The Russians asked to examine them but the US Navy conveniently used them for gunnery practice and sank them in the deep Pacific.

Ballistic missiles were soon taken on board. This sub of the Ohio class is 520ft long, displaces 18,750 tons and carries 24 Tridents. The missile carrying sub has become the principal deterrent weapon of all nuclear equipped navies.