Spitfire over Scapa (May 2011)

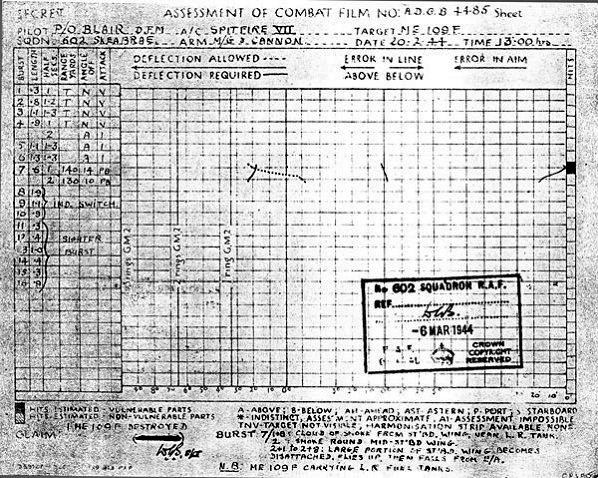

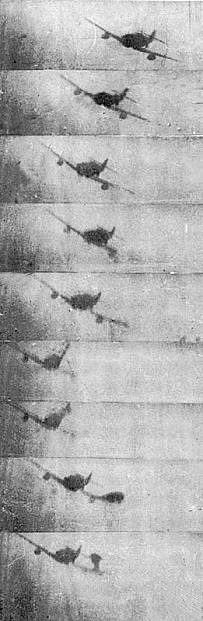

A couple of months ago we reviewed ‘The Big Show’, written by Pierre Clostermann. At the next meeting we were joined by a very welcome guest, Sqn Ldr Ian Blair DFM, who had known Clostermann when they both served in 602 Sqn. He pointed out that Clostermann’s claim to have taken part in an incident in the Orkney Islands was incorrect. Ian has written his own account and has agreed we publish it here in our Newsletter. It is made more vivid by including some frames from his gun camera together with the assessment of the film and the effectiveness of his shooting.

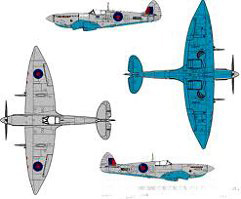

He mentions both Mk VI and Mk VII Spitfires. These marks were produced to intercept high flying German reconnaissance aircraft. Both had extended wingtips and pressurized cockpits. The Mark VI was fitted with a 1,415 hp Merlin 47 and the Mark VII’s Merlin 64 produced 1.660 hp.

He mentions both Mk VI and Mk VII Spitfires. These marks were produced to intercept high flying German reconnaissance aircraft. Both had extended wingtips and pressurized cockpits. The Mark VI was fitted with a 1,415 hp Merlin 47 and the Mark VII’s Merlin 64 produced 1.660 hp.

Ian Blair said '602 Sqn were withdrawn from 2 TAF and sent to the Orkney Islands for a rest, between Jan/Mar 1944. Our training continued and in addition we were required to maintain a standby section in the event of enemy air activity over Scapa Flow, the naval base.

'I was on standby when a ‘scramble’ was received. I immediately took off with my No 2 and as soon as we were airborne received a vector of 085° which indicated a hostile approaching from the direction of the Norwegian coast. My aircraft, a Mk VII H.F. Spitfire had a very good rate of climb, 2,200 f.p.m. at over 25,000 feet. Soon a vapour trail was observed approaching from the east, further height was gained and at about 38,000 ft the hostile below decided to turn back towards the Norwegian coast. With the additional height, I commenced a dive in pursuit. The Spitfire accelerated very quickly and soon the hostile was rapidly being overtaken. I had to throttle back to prevent this.

'My No 2 failed to do the same and overshot me in the dive. Once in the attacking position he opened fire but his guns failed to operate (he was flying a Mk VI Spitfire). I quickly closed to 180 yds and fired a burst. Closing to 140 yds I opened fire again and the starboard wing of the e/a finally broke off in a shower of debris. The e/a crashed into the sea – no sign of the pilot. I set course for base.

'My No 2 called me on the R/T saying that I appeared to have a glycol leak. I immediately gained more height and slowed the aircraft down in an attempt to get the radiator temperature down in an effort to conserve the coolant (I had been told that this was possible while attending a Rolls Royce engine handling course). My No 2 stayed with me and we set course for Skae Brae, having sent the usual ‘Mayday’.

'I was unable to make Skae Brae and decided to set down on the nearest land which was Stronsay, a small island in the Orkney group. I picked my spot, which was a soft peat bog and executed a good landing. I called my No 2 on the R/T to let him know all was well. I suffered a cut on the bridge of my nose and subsequently two black eyes. I walked about 20 yds to a crofter’s cottage and when the old lady opened the door and saw me standing there she knew what was required of her and called the local doc who arrived very quickly (she could speak only Gaelic).

'I had fired a total of 216 rounds of 20mm and 673 rounds of .303. Later in the afternoon, Pierre Clostermann, in the unit Tiger Moth, collected me from Stronsay – his only involvement in the episode. The removal of the Spitfire from the island took 3 weeks.

'The Control Centre at RAF Kirkwall was excellent. The RN C-in-C personally sent for me to thank me and to receive a person to person account of the operation.

'The above operation was the basis of a chapter in ‘The Big Show’, written by Pierre Clostermann, although his only involvement was to ferry me back to the unit'.

'I was on standby when a ‘scramble’ was received. I immediately took off with my No 2 and as soon as we were airborne received a vector of 085° which indicated a hostile approaching from the direction of the Norwegian coast. My aircraft, a Mk VII H.F. Spitfire had a very good rate of climb, 2,200 f.p.m. at over 25,000 feet. Soon a vapour trail was observed approaching from the east, further height was gained and at about 38,000 ft the hostile below decided to turn back towards the Norwegian coast. With the additional height, I commenced a dive in pursuit. The Spitfire accelerated very quickly and soon the hostile was rapidly being overtaken. I had to throttle back to prevent this.

'My No 2 failed to do the same and overshot me in the dive. Once in the attacking position he opened fire but his guns failed to operate (he was flying a Mk VI Spitfire). I quickly closed to 180 yds and fired a burst. Closing to 140 yds I opened fire again and the starboard wing of the e/a finally broke off in a shower of debris. The e/a crashed into the sea – no sign of the pilot. I set course for base.

'My No 2 called me on the R/T saying that I appeared to have a glycol leak. I immediately gained more height and slowed the aircraft down in an attempt to get the radiator temperature down in an effort to conserve the coolant (I had been told that this was possible while attending a Rolls Royce engine handling course). My No 2 stayed with me and we set course for Skae Brae, having sent the usual ‘Mayday’.

'I was unable to make Skae Brae and decided to set down on the nearest land which was Stronsay, a small island in the Orkney group. I picked my spot, which was a soft peat bog and executed a good landing. I called my No 2 on the R/T to let him know all was well. I suffered a cut on the bridge of my nose and subsequently two black eyes. I walked about 20 yds to a crofter’s cottage and when the old lady opened the door and saw me standing there she knew what was required of her and called the local doc who arrived very quickly (she could speak only Gaelic).

'I had fired a total of 216 rounds of 20mm and 673 rounds of .303. Later in the afternoon, Pierre Clostermann, in the unit Tiger Moth, collected me from Stronsay – his only involvement in the episode. The removal of the Spitfire from the island took 3 weeks.

'The Control Centre at RAF Kirkwall was excellent. The RN C-in-C personally sent for me to thank me and to receive a person to person account of the operation.

'The above operation was the basis of a chapter in ‘The Big Show’, written by Pierre Clostermann, although his only involvement was to ferry me back to the unit'.

The explanation of how the analysis of Ian Blair’s shooting was derived comes appropriately, from Pierre Clostermann’s book, ‘The Big Show’.

'Next to the starboard gun on the Spitfire’s wing was mounted a 16 mm camera, running at 12 images per second and meticulously regulated by micrometric screws. It was set up to centre on the exact point where the aircraft’s weapons converged, with the camera operating automatically when the guns fired. It was this point, where the bullets should hit their target, that was filmed, with a fairly big image to make allowance for angles of fire of up to 90°.

'After the combat, the film was passed image by image through a special projector fitted to a long table – standard installation on all British fighter bases. A graduated copper rail extending from one end of the table to the other made it possible to slide along a rigorously exact 1:72 model of the enemy aircraft, mounted on a swivel with a protractor showing the angles, all in front of a pivoting screen on which was drawn the circle of the collimator sights. The model was moved in the illuminated beam of the projector until its shadow coincided exactly with the image on the screen. It was then possible to read the distance of fire on the graduation of a ruler and the protractor would give the angle. The combat report would give a rough indication of the speed at which things had happened and so it was possible to judge whether the firing correction in relation to the trajectory of travel was good. It was diabolically precise and often the impact of explosive projectiles – machine-gun bullets and AP bullets did not always leave visible signs on the target – confirmed what the apparatus had indicated'.

'Next to the starboard gun on the Spitfire’s wing was mounted a 16 mm camera, running at 12 images per second and meticulously regulated by micrometric screws. It was set up to centre on the exact point where the aircraft’s weapons converged, with the camera operating automatically when the guns fired. It was this point, where the bullets should hit their target, that was filmed, with a fairly big image to make allowance for angles of fire of up to 90°.

'After the combat, the film was passed image by image through a special projector fitted to a long table – standard installation on all British fighter bases. A graduated copper rail extending from one end of the table to the other made it possible to slide along a rigorously exact 1:72 model of the enemy aircraft, mounted on a swivel with a protractor showing the angles, all in front of a pivoting screen on which was drawn the circle of the collimator sights. The model was moved in the illuminated beam of the projector until its shadow coincided exactly with the image on the screen. It was then possible to read the distance of fire on the graduation of a ruler and the protractor would give the angle. The combat report would give a rough indication of the speed at which things had happened and so it was possible to judge whether the firing correction in relation to the trajectory of travel was good. It was diabolically precise and often the impact of explosive projectiles – machine-gun bullets and AP bullets did not always leave visible signs on the target – confirmed what the apparatus had indicated'.