Empire State Encounter (Nov 2018)

Bill Smith didn’t like the look of the weather when he entered the tower at Bedford Field, an Army airfield near Boston, to file his flight plan. The Met. report confirmed that a heavy storm was coming in from the Atlantic carrying rain in its dense low clouds. Bill wanted to fly to Newark, 200 miles to the south west where he planned to pick up his CO at 10 o’ clock before returning to their home base in South Dakota.

The briefing officer told him that Newark was too busy to accept any more instrument bookings until after 12.30. ‘What’s the weather like at La Guardia?’ asked Bill. (LG was just 5 minutes flying time from Newark). ‘Last report, 1,500 ft ceiling, light rain and local fog’. ‘OK. I’ll fly contact to La Guardia’. Contact meant clear of cloud and Bill was well aware that regulations stated that if the cloud base lowered to less than 1000 ft he should return to Bedford Field.

The briefing officer told him that Newark was too busy to accept any more instrument bookings until after 12.30. ‘What’s the weather like at La Guardia?’ asked Bill. (LG was just 5 minutes flying time from Newark). ‘Last report, 1,500 ft ceiling, light rain and local fog’. ‘OK. I’ll fly contact to La Guardia’. Contact meant clear of cloud and Bill was well aware that regulations stated that if the cloud base lowered to less than 1000 ft he should return to Bedford Field.

27 year old Lt. Col. William Franklin Smith Jr. was not fazed by the weather. He had completed 34 missions in wet and cloudy Europe commanding the 750th Bomb Sqn of B-17s based at RAF Glatton in Cambridgeshire. Twice decorated he had risen to be Deputy Group Commander. After the war ended, the Group had flown their B-17s home across the Atlantic. When they had crossed the coast of Maine Smith had abandoned his previous character as the imposer of flying discipline. Declaring that he could find his destination field ‘with his eyes closed’ he had dived down to tree top height, shouting and whooping as he jinked across towns and buzzed airfields both military and civil in celebration of coming back home.

Now it was Saturday, 28th July 1945. He climbed into the B-25 which his squadron had borrowed. Army no. 0577, it still carried the name Old John Feather Merchant on its nose. Stripped of its turret and guns, wooden benches had been fitted in the space normally occupied by the navigator and radioman. The flight from South Dakota which carried a small group of men from the New York area on leave had been the first time he’d flown a B-25. There had been no problem.

Now it was Saturday, 28th July 1945. He climbed into the B-25 which his squadron had borrowed. Army no. 0577, it still carried the name Old John Feather Merchant on its nose. Stripped of its turret and guns, wooden benches had been fitted in the space normally occupied by the navigator and radioman. The flight from South Dakota which carried a small group of men from the New York area on leave had been the first time he’d flown a B-25. There had been no problem.

His passenger was Sgt Christopher Domitrovich. As an experienced a crew chief, albeit on C-47s, he had inspected and fuelled the B-25. He sat in the co-pilot’s seat and read out the check list for Smith. The engines were running and they were about to taxi out when a Jeep drew up. A young sailor, Albert Perna, jumped out, waving an authorization paper. Granted compassionate leave he was going home to his parents who had just heard that their other son had been killed in the South Pacific.

(The picture is not 0577).

(The picture is not 0577).

‘Army 0577 – cleared for take-off’. The B-25 lifted into the leaden sky. The brief climb ended at cloud base, little more than 1000 ft with patches of lower cloud and fog. Cruising at 230 mph, Smith navigated by using an en-route radio beacon at Providence and then following the coast line. He could expect little help from Domitrovich. He contacted New York Centre but they were too busy to talk to him and told him speak to La Guardia when he got there.

On his first contact with La Guardia he said he was flying at 650 ft with 15 miles to go and asked for the weather at Newark. Controller Victor Barden was busy. He told Smith to contact Newark on 341 k/c or the Army Flight Service Centre. Evidently, Smith wanted to stay legal by having his flight plan closed by La Guardia so that he could then divert to Newark and get there by 10 o’ clock to pick up his CO and the other passengers. He persisted and spoke to Barden again. Smith was told that he was violating airspace and should clear off to the south east, wait in a holding pattern and contact the Army Flight Service Centre.

Air traffic control in 1945 was much less sophisticated than today. Radar was still quite basic. An aeroplane would appear as a smudgy green spot on a small screen with no indication of height or even which smudge was which aeroplane. To complicate the picture the rotating aerial also picked up nearby ground returns and they were plentiful in the New York area. GCA (Ground Controlled Approach) was available but it was slow and could handle only one plane at a time. First they had to select the correct smudge on the screen, helped by using radio D/F to get a bearing and confirm the choice by asking the pilot to do a 90° turn. Then the approach controller would direct the pilot to a position 10 miles from the runway where he could be handed over to the Talk-down Controller. Operating on a different radio frequency he would give a commentary guiding the pilot on the correct glide slope down to within ¼ mile of the runway.

ILS (Instrument Landing System), where the pilot can follow a beam down to the runway, was still in its early stages of development. It was unreliable and fitted to few aeroplanes. Most pilots were familiar with and preferred to use SBA, the Standard Beam Approach which broadcast ‘A’ or ‘N’ on either side of a radio beam lined up with the runway. Beacons interrupted with a signal to indicate how far they were from the runway. Controllers kept planes separate by stacking them at different heights over beacons or in rough positions, like ‘south east of the field’, which is where Barden put Smith’s B-25.

Victor Barden was really busy. He had one airliner on the approach and several stacked. He had lost touch with a navy plane which had had radio failure. In all this he was also trying to time the release of planes from the take-off queue whenever a gap appeared. Smith’s intrusion into his busy life really tried his patience. An attempt to hand him over to the Army Control Centre failed. The officer on duty there was fending off a 5-star general who was insisting on priority to land at nearby Mitchell Field on Long Island. He passed Smith back to Barden. ‘Just give the pilot the Newark weather and then advise me of his intentions’, he said.

‘0577 - Newark’s ceiling 1000, lower broken. Visibility 2¼ miles. Advise intentions.’ That was enough for Smith to abandon his flight plan to land at La Guardia.

‘I’ll go contact to Newark’.

‘0577 maintain 3 miles, repeat, 3 miles visibility. If unable return to La Guardia’.

‘Roger, will do’.

'Oh, 0577. At present I can’t see the top of the Empire State building’.

Roger Tower. Thank you’.

It was 0935hrs and Smith must have thought he would comfortably get to Newark by 1000.

What happened next was pieced together from witness statements.

On his first contact with La Guardia he said he was flying at 650 ft with 15 miles to go and asked for the weather at Newark. Controller Victor Barden was busy. He told Smith to contact Newark on 341 k/c or the Army Flight Service Centre. Evidently, Smith wanted to stay legal by having his flight plan closed by La Guardia so that he could then divert to Newark and get there by 10 o’ clock to pick up his CO and the other passengers. He persisted and spoke to Barden again. Smith was told that he was violating airspace and should clear off to the south east, wait in a holding pattern and contact the Army Flight Service Centre.

Air traffic control in 1945 was much less sophisticated than today. Radar was still quite basic. An aeroplane would appear as a smudgy green spot on a small screen with no indication of height or even which smudge was which aeroplane. To complicate the picture the rotating aerial also picked up nearby ground returns and they were plentiful in the New York area. GCA (Ground Controlled Approach) was available but it was slow and could handle only one plane at a time. First they had to select the correct smudge on the screen, helped by using radio D/F to get a bearing and confirm the choice by asking the pilot to do a 90° turn. Then the approach controller would direct the pilot to a position 10 miles from the runway where he could be handed over to the Talk-down Controller. Operating on a different radio frequency he would give a commentary guiding the pilot on the correct glide slope down to within ¼ mile of the runway.

ILS (Instrument Landing System), where the pilot can follow a beam down to the runway, was still in its early stages of development. It was unreliable and fitted to few aeroplanes. Most pilots were familiar with and preferred to use SBA, the Standard Beam Approach which broadcast ‘A’ or ‘N’ on either side of a radio beam lined up with the runway. Beacons interrupted with a signal to indicate how far they were from the runway. Controllers kept planes separate by stacking them at different heights over beacons or in rough positions, like ‘south east of the field’, which is where Barden put Smith’s B-25.

Victor Barden was really busy. He had one airliner on the approach and several stacked. He had lost touch with a navy plane which had had radio failure. In all this he was also trying to time the release of planes from the take-off queue whenever a gap appeared. Smith’s intrusion into his busy life really tried his patience. An attempt to hand him over to the Army Control Centre failed. The officer on duty there was fending off a 5-star general who was insisting on priority to land at nearby Mitchell Field on Long Island. He passed Smith back to Barden. ‘Just give the pilot the Newark weather and then advise me of his intentions’, he said.

‘0577 - Newark’s ceiling 1000, lower broken. Visibility 2¼ miles. Advise intentions.’ That was enough for Smith to abandon his flight plan to land at La Guardia.

‘I’ll go contact to Newark’.

‘0577 maintain 3 miles, repeat, 3 miles visibility. If unable return to La Guardia’.

‘Roger, will do’.

'Oh, 0577. At present I can’t see the top of the Empire State building’.

Roger Tower. Thank you’.

It was 0935hrs and Smith must have thought he would comfortably get to Newark by 1000.

What happened next was pieced together from witness statements.

This picture of New York, looking north, was taken in 1945. On the left is the Hudson River, on the right the East River. In the background is the rectangular Central Park whose southern boundary is 59th Street. Close to it is the Midtown group of skyscrapers, including the Empire State building on 34th Street. La Guardia is off the top right hand corner of the picture. Newark is some way off the south west corner.

Smith left his holding pattern near La Guardia and headed west. His intention seems to have been to follow the East River until he could turn right for Newark. Scuttling along at cloud base, which was lower than 900 ft with many scattered lower patches and in heavy rain, Smith was unlikely to have been consulting a map, relying only on recognition of ground features. He would be seeing these at a much closer range than on any previous flight and without the orientation which a wider view in good visibility can give.

There was speculation that he mistook the Queensboro Bridge (below left), which connects with 59th Street, for Brooklyn Bridge at the southern end of the East River. They are clearly different, but the highly stressed Smith was seeing them through a rain-spattered windscreen in murky conditions, flying low at a higher speed than he was used to. Whatever the reason for his decision, immediately after passing Queensboro Bridge he turned right and lowered the landing gear.

There was speculation that he mistook the Queensboro Bridge (below left), which connects with 59th Street, for Brooklyn Bridge at the southern end of the East River. They are clearly different, but the highly stressed Smith was seeing them through a rain-spattered windscreen in murky conditions, flying low at a higher speed than he was used to. Whatever the reason for his decision, immediately after passing Queensboro Bridge he turned right and lowered the landing gear.

He was seen flying west over 51st Street, just south of Central Park. The roof garden on the Rockerfeller Center flashed past, 25 feet below his wheels. Smith must have realised his mistake and opened the throttles pulling the B-25 into a climbing left turn, at the same time selecting ‘gear up’. The Chrysler Building appeared ahead and Smith had to swing into a right turn to avoid it. Over 39th Street, the noise of the engines was recorded by an office Dictaphone machine. Approaching 35th Street, still climbing, Smith turned east again for the river. Over 34th Street, now up to 975 feet, the gear was still retracting when twelve tons of B-25 slammed into the 79th floor of the Empire State Building.

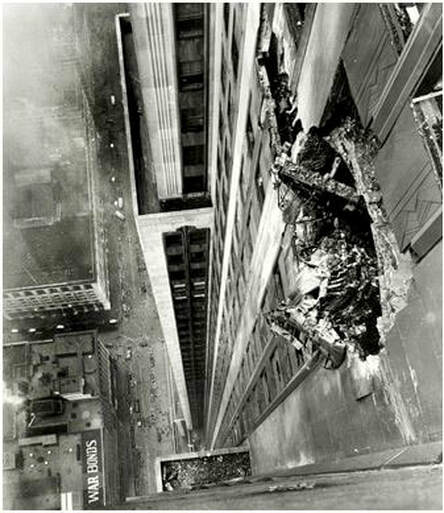

The impact was largely absorbed by the steel structure of the tower but parts of Old John Feather Merchant broke off and catapulted through the building to fall to the street far below. The left engine, a section of the not yet retracted nose gear and stones and mortar from the building all fell to the ground. Astonishingly, there were no reported injuries to any of the hundreds of motorists and pedestrians in the street.

The impact was largely absorbed by the steel structure of the tower but parts of Old John Feather Merchant broke off and catapulted through the building to fall to the street far below. The left engine, a section of the not yet retracted nose gear and stones and mortar from the building all fell to the ground. Astonishingly, there were no reported injuries to any of the hundreds of motorists and pedestrians in the street.

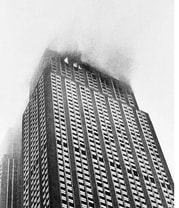

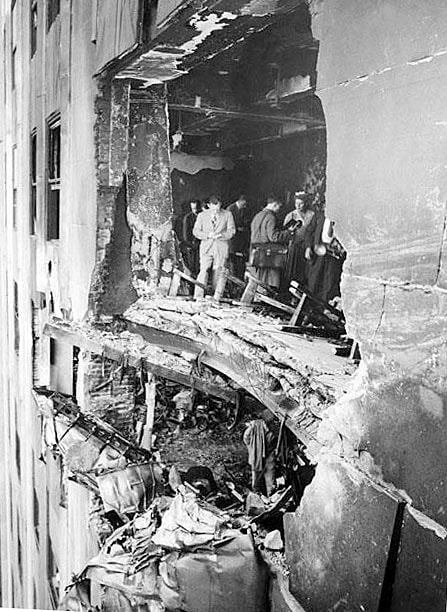

The Empire State Building, shrouded in fog. Wreckage in the street below. A Sculptor's studio, ventilated by a falling engine

The B-25 had struck the office of the Catholic War Relief Services agency. Three ladies were crushed at their desks. Others died when the right engine broke from its mountings, the fuel tanks burst and fire swept through the office. Three of the B-25’s oxygen tanks exploded. The noise was heard in the harbour, triggering a rumour that the Japanese were attacking the city.

The left wing of the turning B-25 had swept through the floor below. It was unoccupied that day – it was Saturday. As well as the three in the bomber, ten others in the building died in the crash and 26 were injured. It could have been much worse.

The right engine had also been torn from its mountings. It penetrated the elevator shafts and plummeted to the basement. On the 80th floor above, the blast blew the operator, 19 year old Betty Lou Oliver, out of her lift. She was given first aid for her burns by some office workers. To get her quickly to more professional help they put her in another lift. They were not to know that the falling engine had broken the lift cables. When the door closed the lift fell, unchecked by the now destroyed safety systems. Betty Lou hung on, almost floating in zero gravity. Building air pressure slowed the fall and the pile of tangled cables acted like a spring to absorb some of the final impact. Most of the lift’s floor was shattered and Betty Lou was found in a corner, alive but with a broken neck, back and pelvis.

The right engine had also been torn from its mountings. It penetrated the elevator shafts and plummeted to the basement. On the 80th floor above, the blast blew the operator, 19 year old Betty Lou Oliver, out of her lift. She was given first aid for her burns by some office workers. To get her quickly to more professional help they put her in another lift. They were not to know that the falling engine had broken the lift cables. When the door closed the lift fell, unchecked by the now destroyed safety systems. Betty Lou hung on, almost floating in zero gravity. Building air pressure slowed the fall and the pile of tangled cables acted like a spring to absorb some of the final impact. Most of the lift’s floor was shattered and Betty Lou was found in a corner, alive but with a broken neck, back and pelvis.

The clear up began immediately. The wreckage had to be broken up into pieces small enough to fit into the elevators. The building was repaired and almost back to normal in three months. The Army paid $288,901.90 in damages.

The Board of Inquiry found no mechanical fault with the B-25’s airframe or its engines – the Dictaphone confirmed that – nor with the way Air Traffic had handled the situation. The cause of the accident rested entirely with Smith. He repeatedly broke regulations and made hazardous decisions with tragic consequences.

Betty Lou’s name lives on in the Guinness Book of Records. Her 970 foot fall is likely to remain an unchallenged record. It happened on the last working day of her summer job but she did come back five months later. Not to work, just to say ‘hello’ and demonstrate her resilience by going up in the lift.

The Board of Inquiry found no mechanical fault with the B-25’s airframe or its engines – the Dictaphone confirmed that – nor with the way Air Traffic had handled the situation. The cause of the accident rested entirely with Smith. He repeatedly broke regulations and made hazardous decisions with tragic consequences.

Betty Lou’s name lives on in the Guinness Book of Records. Her 970 foot fall is likely to remain an unchallenged record. It happened on the last working day of her summer job but she did come back five months later. Not to work, just to say ‘hello’ and demonstrate her resilience by going up in the lift.