Runway in the Sky (Jan 2011)

Back in 1942, the US was embarking on a campaign of retaking the Pacific Islands from the Japanese to establish airstrips. Artillery spotter planes would be useful but there was no place for them on large assault carriers. Then Capt James H Brodie, of the US Coast Artillery and Transportation Corps, had an idea. He persuaded his Corps to allocate $10,000 for his experiments.

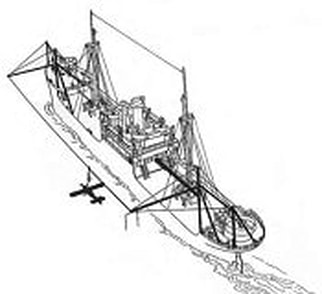

His plan was to put two cranes on the side of a ship and suspend a cable between them which carried a loop – about 4’ wide by 3’ high. The spotter plane, with a hook fixed above the wing centre section, would be aimed by the pilot to engage the loop and ‘land’ on the wire. The running loop pulled out a line from an inertia reel to give braking of about one third ‘g’. This could be adjusted to handle varying weights of the landing aircraft. Take-offs would be easier. There was no aiming involved but the pilot had to make sure his timing was right when he jerked the lanyard which released the plane from the cable.

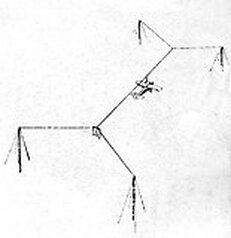

An alternative land- based system used two 65’ masts at each end of the landing wire. Brodie set up this rig at an airfield near New Orleans. Although he was a pilot he was not qualified in the military so he sought volunteers from the transient pilots at the base awaiting postings and a Lt C C Wheeler made the first take-off in August 1943. In September, a regular test pilot, Ray Gregory, was appointed and Brodie rode as passenger on the first test landing. The prop hit the sag in the cable, but Gregory brought his L-5 to a safe emergency landing under the rig.

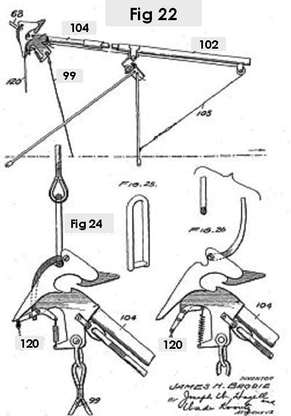

These drawings from the patent show clearly how the mechanism worked. Fig 22 shows the rig fitted to the top of the aeroplane at the moment of landing – 68 is the captured landing strop. The plane’s weight is taken by the cables (99) which are attached to the bottom of the fuselage at the Centre of Gravity and can swing backwards to help to pitch down the decelerating plane and keep its propeller clear of the cable. 104 is a rod which telescopes into 102. These extend on ‘landing’ with some of the shock being progressively absorbed by 105, a rubber cord.

Before take-off, Fig 24, the rods have closed up and cables 99 hang vertically. When flying speed is reached the rig is released by the pilot pulling the release cord, 120, which extends into his cockpit.

Before take-off, Fig 24, the rods have closed up and cables 99 hang vertically. When flying speed is reached the rig is released by the pilot pulling the release cord, 120, which extends into his cockpit.

With the system working well take-offs were achieved in zero wind in 400’, in a moderate breeze in 200’. One confident pilot even removed the undercarriage of a Piper Cub (unofficially, of course) and completed a successful take-off and landing. Next Brodie fitted the rig to a freighter, the City of Dalhart, which used a generous 600’ long cable. In test manoeuvres the spotters flew regularly, including one occasion when all other planes were grounded by fog. The system was officially accepted and it was contracted to be fitted to 25 tank landing craft. However, progress was slow and in the end, only 8 landing craft were Brodie-equipped. But it did see action.

LST-776, unofficially known as USS Brodie, was fitted with the ‘runway on a rope’. The approved procedure was to start with the crane booms over the ship so that the pilot could climb aboard and start the engine before being swung out for take-off. But some pilots preferred to wait until the plane was in the take-off position then to step out, jam their foot between the wheel and the undercarriage leg and reach forward to swing the prop.

Landing was not easy. LSTs have no keel and were prone to roll, even in a slight swell. The long crane arms could be swinging in a 30’ arc, requiring the pilot to time his approach carefully. The cable was only 20” above the prop and when the hook engaged the pilot had to fight his normal landing instincts. Rather than the usual pull back on the stick he had to push the stick firmly forward the keep the prop clear of the cable. However, if he found he was wrong and the hook had not engaged he would find himself diving at the sea with just fractions of a second to recover – but not so violently that he flew up into the cable.

USS Brodie went into action during the invasion of Okinawa. The US Marines first occupied the small rocky Kerama Retto islands 8 miles from the main island. They set up 155mm artillery there which needed spotting planes but there was no place for an airstrip.

A Piper Cub unit operating in the Philippines had hooks rigged on their aircraft. Briefed on, but not practised in its use, they flew to join their ship. The first pilot made five passes before he hooked the cable. Eventually all four Cubs were aboard and ready for action. During the 82 days of the operation one of the Cubs was lost over the side but the others performed well enough for the Brodied LSTs to be included for use in the planned invasion of the Japanese mainland.

Jim Brodie’s system also aroused the interest of the OSS, fore-runner of the CIA. The whole rig could be parachuted in or transported in two trucks. A nine-man crew could have it ready for use in 12 hours. The OSS saw it as a useful way of taking agents and supplies into enemy territory in SE Asia where a wire-in-the-jungle would be almost undetectable.

The dropping of the atomic bombs evaporated all these plans. With the end of the war both Brodie and his test pilot Ray Gregory were recognized by the award of the Legion of Merit.

But Jim still hoped to find a user for his portable runway. He believed he could make a rig capable of handling 7,000 pound aircraft – it could be useful in postal work, for forest rangers in rough country, ship-to-shore ferrying of passengers, even installations on top of large building for commuters or city centre deliveries. It was not to be. Brodie’s ingenious, proven system faded into history and there has been no practical civilian use for it – so far.

Jim Brodie’s system also aroused the interest of the OSS, fore-runner of the CIA. The whole rig could be parachuted in or transported in two trucks. A nine-man crew could have it ready for use in 12 hours. The OSS saw it as a useful way of taking agents and supplies into enemy territory in SE Asia where a wire-in-the-jungle would be almost undetectable.

The dropping of the atomic bombs evaporated all these plans. With the end of the war both Brodie and his test pilot Ray Gregory were recognized by the award of the Legion of Merit.

But Jim still hoped to find a user for his portable runway. He believed he could make a rig capable of handling 7,000 pound aircraft – it could be useful in postal work, for forest rangers in rough country, ship-to-shore ferrying of passengers, even installations on top of large building for commuters or city centre deliveries. It was not to be. Brodie’s ingenious, proven system faded into history and there has been no practical civilian use for it – so far.