Derek Piggott (1922 – 2019) (Mar 2019)

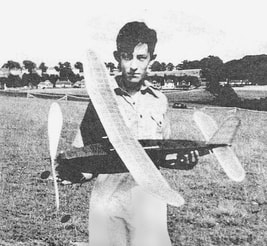

Derek Piggott’s father was an aviation enthusiast and took his young son to every flying event within reach of their home in Sutton, Surrey. A five shilling ride in an Avro 504 cemented Derek’s inherited enthusiasm. With little prospect of learning to fly the real thing, Derek made model aeroplanes – not so easy in the 30s before balsa wood became readily available.

After school, he became an instrument maker at a precision engineering company until he was old enough to join the RAF in 1942. Although he had never shone at school he found it easy to absorb the technicalities of the principles of flight, navigation and meteorology at Initial Training Wing at Scarborough.

He was one of the first pupils in his course to go solo in the Tiger Moth and soon was on his way to Canada. Derek admitted being ‘lucky with his instructors’ - he was rated highly on graduating as a Pilot Officer. He was posted to an instructors’ course and enjoyed teaching others to fly the twin-engined Oxford.

After school, he became an instrument maker at a precision engineering company until he was old enough to join the RAF in 1942. Although he had never shone at school he found it easy to absorb the technicalities of the principles of flight, navigation and meteorology at Initial Training Wing at Scarborough.

He was one of the first pupils in his course to go solo in the Tiger Moth and soon was on his way to Canada. Derek admitted being ‘lucky with his instructors’ - he was rated highly on graduating as a Pilot Officer. He was posted to an instructors’ course and enjoyed teaching others to fly the twin-engined Oxford.

His 21st birthday was spent in Halifax, waiting for the boat which brought him home to England. There he joined the large group of seemingly unwanted aircrew. Many of his colleagues were sent off to unlikely places, some even to drive steam trains. Derek was offered, but managed to avoid, another instructors’ course. He was posted briefly to Witchford, near Ely, as a Flying Control Assistant – a ‘dogsbody’. Back at the holding unit they learned of an opportunity to train as glider pilots – at least that was something positive.

He learned to fly the Hotspur, then the Horsa assault glider. The technique for landing the Horsa under fire was everyone’s favourite. From 2000 ft above the landing site they would lower the huge flaps and dive almost vertically for the hedge, pulling out at the last second. So that the pilots would be useful after landing they had an intensive course involving weapons training, explosives and demolition. Suddenly they were given inoculations and tropical kit, loaded into Dakotas and left for the long haul to Karachi.

Derek spent two years in India. The gliders were never used in action. Apparently, there weren’t any spare Dakotas to tow them although he sometimes flew as a second pilot in a supply dropping Dakota. He had sufficient spare time to keep up with his aeromodelling hobby. On a dump he found some wreckage from the crash of a Sikorski helicopter. A broken rotor blade yielded a good supply of balsa wood which Derek cut into strips for his next model. Then he found better employment. His instructor’s rating got him a posting to the Indian Elementary Flying Training School flying Tiger Moths and Fairchild Cornells. He came home in time to avoid the turmoil of the upheaval when India and Pakistan became independent.

Posted to the Central Flying School Derek’s experience expanded greatly. He flew everything from Chipmunks to Lancasters and Meteors and he became an A1 instructor, the highest category. One of the instructional units he visited was the Gliding Instructors’ School at RAF Detling, near Maidstone. It had been formed to train the instructors who flew the recently introduced two seat training gliders at Air Cadet week-end schools. He found the lightweight soaring gliders interesting and enjoyable to fly. (He continued to fly models. He was good enough to be selected as a member of the British Wakefield Cup team which competed in the World Championships in Akron, Ohio).

For some time, Derek had been trying to get on a course at the Empire Test Pilots’ School. When the posting finally arrived it came at the same time as an offer of a permanent commission. This meant a full medical examination in London. He was staggered to learn that he was suffering from high tone deafness and really wasn’t fit to fly at all. So many pilots were being found to be affected by this that the medical branch soon revised their strict standards and tolerated more practical levels. Not in time for Derek. Any hopes of test flying and a long term career had disappeared.

Derek spent two years in India. The gliders were never used in action. Apparently, there weren’t any spare Dakotas to tow them although he sometimes flew as a second pilot in a supply dropping Dakota. He had sufficient spare time to keep up with his aeromodelling hobby. On a dump he found some wreckage from the crash of a Sikorski helicopter. A broken rotor blade yielded a good supply of balsa wood which Derek cut into strips for his next model. Then he found better employment. His instructor’s rating got him a posting to the Indian Elementary Flying Training School flying Tiger Moths and Fairchild Cornells. He came home in time to avoid the turmoil of the upheaval when India and Pakistan became independent.

Posted to the Central Flying School Derek’s experience expanded greatly. He flew everything from Chipmunks to Lancasters and Meteors and he became an A1 instructor, the highest category. One of the instructional units he visited was the Gliding Instructors’ School at RAF Detling, near Maidstone. It had been formed to train the instructors who flew the recently introduced two seat training gliders at Air Cadet week-end schools. He found the lightweight soaring gliders interesting and enjoyable to fly. (He continued to fly models. He was good enough to be selected as a member of the British Wakefield Cup team which competed in the World Championships in Akron, Ohio).

For some time, Derek had been trying to get on a course at the Empire Test Pilots’ School. When the posting finally arrived it came at the same time as an offer of a permanent commission. This meant a full medical examination in London. He was staggered to learn that he was suffering from high tone deafness and really wasn’t fit to fly at all. So many pilots were being found to be affected by this that the medical branch soon revised their strict standards and tolerated more practical levels. Not in time for Derek. Any hopes of test flying and a long term career had disappeared.

It needed the recommendation from some senior officers who knew him well to get the posting he requested. He could go back to the cumbersomely named Home Command Gliding Instructors’ School at Detling as the Chief Instructor and carry on flying gliders. It was more than flying. He needed to devise a practical method of instruction for dual control gliders. For years, glider pilots had been trained by the ‘solo’ method, devised in Germany in the 20s – wing balancing in a stationary single seat glider, more of it whilst being dragged over the ground by a winch, faster winching so that the glider hopped briefly off the ground, slightly higher hops and so interminably on. Now that there were two-seaters for launching to 1,000ft ‘normal’ flying instruction could be given. Someone had taken the RAF’s flying training manual and simply removed any reference to engines.

Derek realised that an entirely different method was needed. The average time for tuition in a training glider is as little as 4 minutes, preceded by the launch and ending by having to concentrate on the approach and landing. He abandoned the sequence of lessons in the standard training manual and developed a number of prescribed lessons to take maximum advantage of the limited flight time with appropriate pre- and post-flight briefings given on the ground. In practice this was proved to be so effective that, provided the training was continuous, as on a week’s course, it became usual to have a pupil ready to be sent solo (and to be capable of coping with cable breaks and emergencies) after as few as 15 launches. His methods were first used by the Air Cadets schools but were soon adopted by civilian clubs and formed the basis for the training schemes still in use across the world today. It is widely acknowledged that Derek Piggott ‘taught the world to glide’. His achievement was acknowledged by the award of the Queen’s Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air.

Detling ran a series of week-long courses for gliding school instructors. The staff instructors there also visited all the week-end schools twice a year to spread the word. The number of pupils qualifying for their ‘A’ and ‘B’ certificate increased and the accident rate fell dramatically. To raise the School’s profile they entered two T-21 Sedbergh gliders in the 1953 National Championships, the justification being that it would be valuable experience for the ATC cadets they took with them to help rig and de-rig the gliders. The T-21 was a hopeless competition glider. Its slow, stately tight circles were good for gaining height in thermals but with a gliding angle of just 18:1 got it nowhere when trying to travel cross country.

Detling ran a series of week-long courses for gliding school instructors. The staff instructors there also visited all the week-end schools twice a year to spread the word. The number of pupils qualifying for their ‘A’ and ‘B’ certificate increased and the accident rate fell dramatically. To raise the School’s profile they entered two T-21 Sedbergh gliders in the 1953 National Championships, the justification being that it would be valuable experience for the ATC cadets they took with them to help rig and de-rig the gliders. The T-21 was a hopeless competition glider. Its slow, stately tight circles were good for gaining height in thermals but with a gliding angle of just 18:1 got it nowhere when trying to travel cross country.

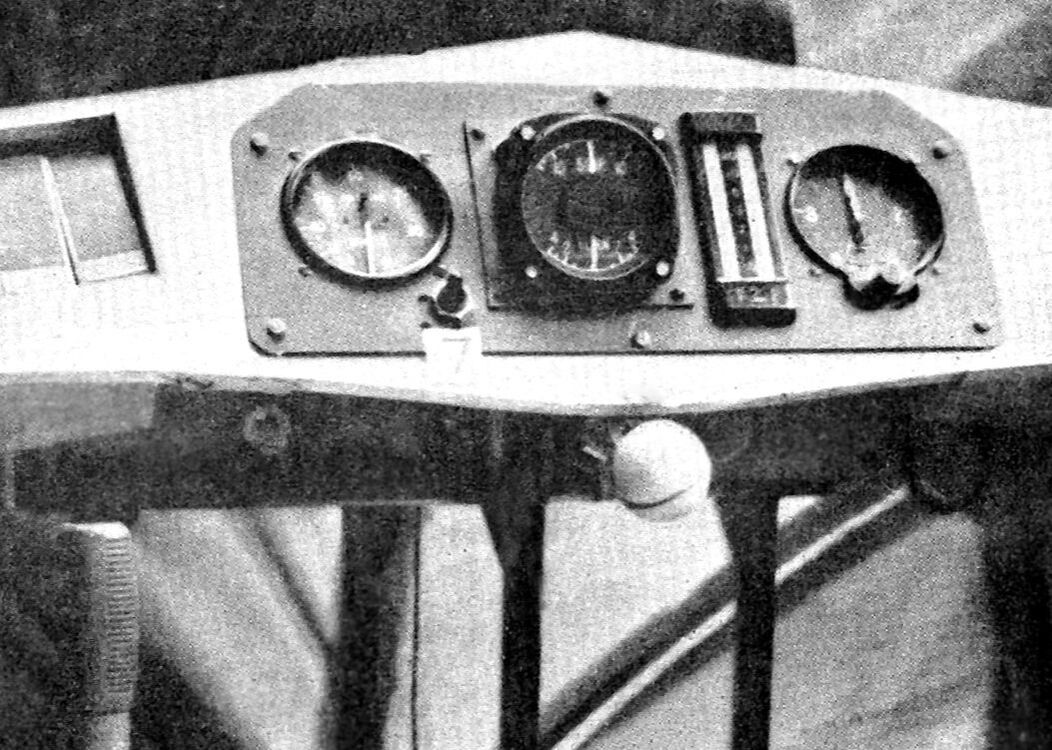

Derek launched on a distance task one day when clouds were building rapidly. He soon found a good thermal which lifted him to the base of a large cloud building over Sheffield. The Sedbergh had only basic instruments - airspeed indicator, turn and slip indicator, variometer, to show rate of climb/descent and altimeter – there was no artificial horizon. Most pilots would avoid flying in cloud with such a limited panel. It is very easy for a turn to develop into a spiral dive. Derek was skilled enough to keep the Sedbergh circling in the rapidly lifting thermal and enjoyed a remarkable rate of climb. The cloud was building into a thunderstorm.

The altimeter wound past 10,000 ft. Alongside Derek sat Cadet Whalley. With nothing to do or see he was bored, getting colder and increasingly frightened. He kept asking to go down. Derek tried to keep him interested in the possibility of breaking a record – the gain of height in a two seater glider was becoming a possible achievement. Derek couldn’t remember what the figure was so he determined to extract the maximum from the cloud’s lift. Continuing the climb he encouraged Brian Whalley to keep awake and to breathe deeply to improve his oxygen intake. The occasional sharp elbow was needed from time to time. Eventually, the thermal became ragged and they could climb no higher. Derek straightened up to head downwind. They popped out of the side of the cu-nim at 17,000 ft. The record for this unlikely glider was firmly in the bag (without oxygen, without parachutes and improperly dressed). From such a height, even a Sedbergh can go a long way. They still had height to burn off when they reached the coast and landed in a field near Grimsby.

At the end of the year, with no hope of a career, Derek left the RAF. He had effectively been head hunted by Lasham Gliding Society. Originally a group of separate gliding cubs operating from the same airfield they combined to become the largest gliding club in the world, bought the airfield to become securely based and realised that they had to be run as a profitable business. Many members were private owners but the club maintained a fleet of single seat gliders for rent. The club’s training gliders were used to attract new members and teach them to fly so as to encourage them to stay as permanent members. As General Manager, Derek had to set up an organisation which made most effective use of his training scheme and provide facilities and equipment needed for the many pilots whose aim was cross country flying.

His original work had been covered the early stages of gliding training – the Air Cadets trained people to fly three solo circuits then sent them off, if they wanted more flying and could afford it, to a civilian gliding club. Now Derek devised schemes which taught soaring and cross country flying. He found that most trainees were flying with a number of instructors and becoming confused by the different ways they taught. A consistent line of instructional ‘patter’ was developed and sets of briefing cards and progress cards appeared. Derek used the new-fangled tape recorder to have a range of his talks available on every possible subject from basic effects of controls to field landings after cross county flights.

He spent as little time in the office as possible, much preferring to be on the field and in the cockpit. No trainee can land at the launch point so instructors spend much of their time tramping along beside a glider being towed at walking pace back to the launching queue. One new member noticed this and saw a marketing opportunity. He worked for a shoe manufacturer and asked Derek if he would wear newly designed shoes to check their robustness. He did so much walking on grass and runways that he was wearing out a pair of shoes in six weeks. Useful knowledge for the shoemaker and an unusual source of income for Lasham.

The altimeter wound past 10,000 ft. Alongside Derek sat Cadet Whalley. With nothing to do or see he was bored, getting colder and increasingly frightened. He kept asking to go down. Derek tried to keep him interested in the possibility of breaking a record – the gain of height in a two seater glider was becoming a possible achievement. Derek couldn’t remember what the figure was so he determined to extract the maximum from the cloud’s lift. Continuing the climb he encouraged Brian Whalley to keep awake and to breathe deeply to improve his oxygen intake. The occasional sharp elbow was needed from time to time. Eventually, the thermal became ragged and they could climb no higher. Derek straightened up to head downwind. They popped out of the side of the cu-nim at 17,000 ft. The record for this unlikely glider was firmly in the bag (without oxygen, without parachutes and improperly dressed). From such a height, even a Sedbergh can go a long way. They still had height to burn off when they reached the coast and landed in a field near Grimsby.

At the end of the year, with no hope of a career, Derek left the RAF. He had effectively been head hunted by Lasham Gliding Society. Originally a group of separate gliding cubs operating from the same airfield they combined to become the largest gliding club in the world, bought the airfield to become securely based and realised that they had to be run as a profitable business. Many members were private owners but the club maintained a fleet of single seat gliders for rent. The club’s training gliders were used to attract new members and teach them to fly so as to encourage them to stay as permanent members. As General Manager, Derek had to set up an organisation which made most effective use of his training scheme and provide facilities and equipment needed for the many pilots whose aim was cross country flying.

His original work had been covered the early stages of gliding training – the Air Cadets trained people to fly three solo circuits then sent them off, if they wanted more flying and could afford it, to a civilian gliding club. Now Derek devised schemes which taught soaring and cross country flying. He found that most trainees were flying with a number of instructors and becoming confused by the different ways they taught. A consistent line of instructional ‘patter’ was developed and sets of briefing cards and progress cards appeared. Derek used the new-fangled tape recorder to have a range of his talks available on every possible subject from basic effects of controls to field landings after cross county flights.

He spent as little time in the office as possible, much preferring to be on the field and in the cockpit. No trainee can land at the launch point so instructors spend much of their time tramping along beside a glider being towed at walking pace back to the launching queue. One new member noticed this and saw a marketing opportunity. He worked for a shoe manufacturer and asked Derek if he would wear newly designed shoes to check their robustness. He did so much walking on grass and runways that he was wearing out a pair of shoes in six weeks. Useful knowledge for the shoemaker and an unusual source of income for Lasham.

Derek practised what he preached. He entered gliding competitions – and won three regional contests. And he couldn’t resist the occasional crack at a record.

An opportunity came in July 1955. In an echo of his astonishing flight in the old T-21 two years before he eyed an approaching rain shower under a large and growing cumulus cloud. As the training gliders were being hustled into the hangars he pulled out a Skylark 2 and found a barograph (to record the height) and his parachute. Another Skylark 2

An opportunity came in July 1955. In an echo of his astonishing flight in the old T-21 two years before he eyed an approaching rain shower under a large and growing cumulus cloud. As the training gliders were being hustled into the hangars he pulled out a Skylark 2 and found a barograph (to record the height) and his parachute. Another Skylark 2

Avoiding using the winch for launching - a lightning strike on the cable could be fatal - he was towed off by a Tiger Moth just as the rain reached the airfield boundary. He released the tow rope at 1800 ft, already in lift. Nevertheless, he opened the airbrakes and dived down 200 ft. This would make a clear mark on the barograph trace to show when he started his climb. The aim was to gain 5000 metres (16,504 ft) which would award him a Diamond Certificate. Back in the lift, he switched on the turn and slip indicator and was drawn into the cloud at 3,000 ft. The lift was strong and at 14,000 ft he ran into severe turbulence, then was deafened by the sound of hail hitting the glider.

He felt electric shocks from the stick and airbrake lever. They became more violent and painful. Blue sparks flashed between the rudder cables. Derek realised that he was shouting, as if it would relieve the pain. Ice was forming on the leading edges of the wings and he had to keep moving the stick to prevent the ailerons from freezing up. The altimeter reached 20,000 ft. In his oxygen deprived state he couldn’t work out if that was high enough for the Diamond. He could be sure that he had definitely had enough of the cloud. He straightened up to get out of the lift and opened the airbrakes.

He felt electric shocks from the stick and airbrake lever. They became more violent and painful. Blue sparks flashed between the rudder cables. Derek realised that he was shouting, as if it would relieve the pain. Ice was forming on the leading edges of the wings and he had to keep moving the stick to prevent the ailerons from freezing up. The altimeter reached 20,000 ft. In his oxygen deprived state he couldn’t work out if that was high enough for the Diamond. He could be sure that he had definitely had enough of the cloud. He straightened up to get out of the lift and opened the airbrakes.

It wasn’t until he examined the barograph trace after the flight that he found the glider went on climbing with its airbrakes open until it reached 23,000ft. He was only half aware of the descent. When the cloud finally released him it was difficult to see the ground until the frozen rain on the canopy melted. One and a half hours after take off, his friends were relieved to see him approach and land. The airfield had been flooded by torrential rain and lightning strikes had killed several people nearby and at Ascot racecourse. Although he had earned his Diamond – and the UK altitude record - Derek realised he had been very lucky. He resolved to avoid all thunderstorms in the future and advise other glider pilots not to be ‘as stupid as I was’.

Damage caused by hail. There were numerous burn holes

in and around the cockpit caused by lightning strikes.

Damage caused by hail. There were numerous burn holes

in and around the cockpit caused by lightning strikes.

I959 was the 50th anniversary of Bleriot’s Channel flight. The Daily Mail offered a prize for a celebratory race from Marble Arch to the Arc de Triomphe. There would be prizes for speed, originality and novelty. The chat in the Lasham bar discussed this and Derek said that if a glider were to compete then a primary glider would be most like Bleriot’s aeroplane. The rumour spread and several members came to offer Derek their help. Though he insisted that he never meant to fly in the race it was too late. A primary was borrowed, registered and fitted with an airspeed indicator and altimeter to make it officially ‘airworthy’. Derek was committed.

On the due day the primary, on its trailer, was taken to Marble Arch and Derek checked out at the start point. They drove to Blackbushe, an airport with full customs facilities and towed off from there. Derek was warmly wrapped for his breezy ride and also wearing the required life jacket for the Channel crossing. They had to land at Le Touquet to clear customs, surprising the official when he saw the planeur listed on his teleprinter sheet. French officialdom relaxed enough to charge just one landing fee for the tug - the glider was free. After the briefest interval they took off again heading for a glider field at Beyne on the outskirts of Paris. The primary was de-rigged, put on a trailer and driven to the Arc de Triomphe. Their elapsed time was 11 hours 20 minutes and they were the only entrant who checked in both machine and pilot at both start and finish.

On the due day the primary, on its trailer, was taken to Marble Arch and Derek checked out at the start point. They drove to Blackbushe, an airport with full customs facilities and towed off from there. Derek was warmly wrapped for his breezy ride and also wearing the required life jacket for the Channel crossing. They had to land at Le Touquet to clear customs, surprising the official when he saw the planeur listed on his teleprinter sheet. French officialdom relaxed enough to charge just one landing fee for the tug - the glider was free. After the briefest interval they took off again heading for a glider field at Beyne on the outskirts of Paris. The primary was de-rigged, put on a trailer and driven to the Arc de Triomphe. Their elapsed time was 11 hours 20 minutes and they were the only entrant who checked in both machine and pilot at both start and finish.

The next day, Derek flew the whole thing in reverse. The winner used motor cycles, helicopters and a Hunter to do the trip in 40 mins 44 secs.

The Special Prize went to a British European group who used a scheduled flight on a Comet and normal surface transport.

The primary glider got nothing.

The Special Prize went to a British European group who used a scheduled flight on a Comet and normal surface transport.

The primary glider got nothing.

Later in the same year a group of students visited Lasham with a strange request. Could they use the airfield to test the aeroplane they were building? Spurred on by the £50,000 Kremer Prize they had designed SUMPAC, the Southampton University Man Powered Aircraft. And would Derek train the pilot, a long distance runner who had shown himself able to produce the power they had calculated was needed to fly the machine.

It took two years to come to fruition and Sumpac arrived at Lasham late in 1961. The runner had proved to be a very poor pilot and unlikely to be able to handle the unusual controls of Sumpac with a wheel on top of the stick which rotated for rudder control. Although Derek was no athlete he felt fit enough to offer to do the initial testing.

This was very useful for the team because he was able to make some valuable suggestions for improvements to the controls and aerodynamics of the machine. Frequent breakages and strengthening of other parts prolonged the tests which could only be carried out on windless days – or very early mornings. It was on one run on the morning of 9th November 1961 when Derek felt that the drive felt odd and seemed to be slipping. It took some time and much discussion to realise that Sumpac had actually been off the ground and the propeller had not been producing enough thrust to keep it airborne. The day was spent adjusting the drive and propeller.

It took two years to come to fruition and Sumpac arrived at Lasham late in 1961. The runner had proved to be a very poor pilot and unlikely to be able to handle the unusual controls of Sumpac with a wheel on top of the stick which rotated for rudder control. Although Derek was no athlete he felt fit enough to offer to do the initial testing.

This was very useful for the team because he was able to make some valuable suggestions for improvements to the controls and aerodynamics of the machine. Frequent breakages and strengthening of other parts prolonged the tests which could only be carried out on windless days – or very early mornings. It was on one run on the morning of 9th November 1961 when Derek felt that the drive felt odd and seemed to be slipping. It took some time and much discussion to realise that Sumpac had actually been off the ground and the propeller had not been producing enough thrust to keep it airborne. The day was spent adjusting the drive and propeller.

The evening was damp and cold, but windless. Someone had invited a member, who was an ex-Pathe news cameraman, to bring his camera - ‘just in case’. Derek was fitted into the seat and the nose bolted on. Then - everything worked. Sumpac accelerated down the runway, lifted off and kept flying. A wing dropped slightly and the sluggish ailerons slowly righted it. The elevator was over sensitive but the flight was long enough to be the first ever take off, flight and landing of a man-powered aircraft – and it was all recorded on film.

The Southampton team were a long way from the prize (this required flying a figure of eight which wasn’t achieved until 1977) but they were ahead of their rivals at Hatfield who flew Puffin two weeks later. (Derek was also asked to fly the Puffin later in its development). He made 40 flights in Sumpac, the longest covering 650 yards. However, he always said that the first flight in Sumpac was one of the most thrilling and memorable moments of his life.

To add to his achievements in 1961, he had won the glider National Aerobatic Championships.

Derek got involved in film work when he was asked to fly the aeroplanes that had been built in 1964 for Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines. He flew them all, including the little Demoiselle - but he was too heavy to achieve more than a hop in that. Some were marginal. The Antoinette, which in the film won the race, had to be kept below 40 m.p.h. At higher speeds it suffered from ‘trampling’, which began as an inadvertent warping of one wing which caused increasingly rapid rolling from side to side and could end in a wing breaking off. The Eardley Billing (German - and with extra painted panels Japanese entrants) stretched its rigging wires on every flight. The Boxkite needed a third rudder before it would turn properly and its engine overheated and seized. It was fixed by reaming out the carburettor jet so that the extra fuel cooled the engine. Derek was then able to fly the Boxkite between filming locations to save the complicated de-rigging of its multi-braced structure.

It was at Skegness where he had to do the landing after the Boxkite had been sabotaged by cutting the bungee which held on one pair of wheels. There were several rehearsals, with all four wheels of course, before the final shoot. Dozens of extras were involved in and around the viewing stands. Then the director decided that it was too late in the day and the light wasn’t good enough. ‘We’ll do it tomorrow’.

To add to his achievements in 1961, he had won the glider National Aerobatic Championships.

Derek got involved in film work when he was asked to fly the aeroplanes that had been built in 1964 for Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines. He flew them all, including the little Demoiselle - but he was too heavy to achieve more than a hop in that. Some were marginal. The Antoinette, which in the film won the race, had to be kept below 40 m.p.h. At higher speeds it suffered from ‘trampling’, which began as an inadvertent warping of one wing which caused increasingly rapid rolling from side to side and could end in a wing breaking off. The Eardley Billing (German - and with extra painted panels Japanese entrants) stretched its rigging wires on every flight. The Boxkite needed a third rudder before it would turn properly and its engine overheated and seized. It was fixed by reaming out the carburettor jet so that the extra fuel cooled the engine. Derek was then able to fly the Boxkite between filming locations to save the complicated de-rigging of its multi-braced structure.

It was at Skegness where he had to do the landing after the Boxkite had been sabotaged by cutting the bungee which held on one pair of wheels. There were several rehearsals, with all four wheels of course, before the final shoot. Dozens of extras were involved in and around the viewing stands. Then the director decided that it was too late in the day and the light wasn’t good enough. ‘We’ll do it tomorrow’.

The next morning the wind had changed direction by 180º. The director couldn’t afford to change everything round so the scene had to be shot as rehearsed. Admittedly, it wasn’t much of a breeze but it meant that Derek would now be landing downwind.

In the event, it was a non-event. The wheel-less skid slid easily over the ground and the Boxkite swung only slightly to the right.

In the event, it was a non-event. The wheel-less skid slid easily over the ground and the Boxkite swung only slightly to the right.

Next came The Blue Max, for which Derek was the Chief pilot i.e. advisor on what film effect was possible and how it could be achieved, what was safe and what was downright dangerous. Pilots new to film work were always surprised at how close to the camera and to other aeroplanes they had to fly. Every scene had to be meticulously planned and rehearsed. Most were shot several times from different angles. Derek flew several of the aeroplanes and was justifiably pleased by two scenes. One was unrehearsed. At the end of a day when towering cumulus clouds had prevented any planned scenes to be shot the film helicopter and Derek in the Morane 230 took off and climbed above the top of the clouds to see if they could get any good shots which might be useful in the film.

They broke through into wonderful evening light and Derek indulged in spins and uninhibited aerobatics around the helicopter.

When the rushes were projected to the pilots and film crew the next day they generated spontaneous applause. Most of the footage was usable in the film.

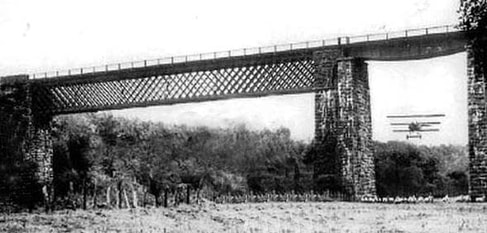

The other scene was very carefully planned and rehearsed. The plot called for two Fokker triplanes to fly through the arch of a bridge – not just the main arch, but also one of the narrow arches with only four feet clearance from either wing tip. None of the other pilots wanted to do this and Derek, as chief pilot, felt obliged to see if he could do it safely.

He had two yellow painted scaffolding poles driven into the ground on the airfield and a man stood with a flag in line with the poles. Derek dived down and flew over the flagman. When it was raised every time the poles were transferred to the bridge site. This time he dived and flew over the bridge a few times. Now, with the cameras rolling, he went through the arch.

The sheep were added to prove to viewers that the triplane and the bridge were real. They ran about on the first couple of passes, then they ignored the noisy triplane.

There were two distinctly different triplanes to be filmed so Derek flew through the main arch 15 times and through the narrow arch 18 times.

The sheep were added to prove to viewers that the triplane and the bridge were real. They ran about on the first couple of passes, then they ignored the noisy triplane.

There were two distinctly different triplanes to be filmed so Derek flew through the main arch 15 times and through the narrow arch 18 times.

More film work followed. Darling Lily, Agatha, Slipstream and Villa Rides. Villa’s plot called for an aircraft to crash through a barbed wire barricade at the foot of a cliff which had an old castle on the top. The film company had found the very place in Spain. The approach was to be made over a river and there could be only one take – because of the cliff face there was no overshoot for a practice run. The aircraft in previous flying shots was a Curtis Jenny.

Derek remembered a time in India when he had had an engine failure in a Tiger Moth. With only tiny paddy fields to land in the wheels had hit an embankment and broken off and the Tiger skidded along on its belly in a ‘fairly safe’ crash.

An old Tiger Moth was found, made airworthy and had some extra struttery attached to make it look a bit like a Jenny. Derek arranged for the pin in the joint where the undercarriage struts met to be loosened and a wire attached. He planned to pull out the pin on the approach leaving just a loop of thin locking wire which would break easily when he hit the barricade.

When all the film crews were ready, an ambulance and fire fighters in attendance and the light was right Derek took off. The old Tiger was flying sweetly and he felt sorry that he was going to deliberately destroy it.

All went according to plan. He hit the barrier, the wheels spread out and he skidded to a halt just feet away from a sandbagged gun placement. Here he is, all smiles, walking away carrying his extra anti-crash padding.

It was some time later when he realised that all the cameras had been pointing away from the cliff and he could have done the crash on another part of the river without the threat of a cliff looming ahead.

All went according to plan. He hit the barrier, the wheels spread out and he skidded to a halt just feet away from a sandbagged gun placement. Here he is, all smiles, walking away carrying his extra anti-crash padding.

It was some time later when he realised that all the cameras had been pointing away from the cliff and he could have done the crash on another part of the river without the threat of a cliff looming ahead.

It was his knowledge of film makers’ requirements that brought Derek his next job. Even though he’d never flown an airship he was hired for Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

The airship was very pretty but very unstable. Adding a large fin didn’t help because the structure was so flexible. Every flight ended in an uncontrolled crash but the film company persisted and had it repaired, several times. On its final flight it was launched near the windmill which features in the film and the cameras caught what they could.

Only 12 seconds of genuine the airship’s not very controlled flight appear in the film.

The airship was very pretty but very unstable. Adding a large fin didn’t help because the structure was so flexible. Every flight ended in an uncontrolled crash but the film company persisted and had it repaired, several times. On its final flight it was launched near the windmill which features in the film and the cameras caught what they could.

Only 12 seconds of genuine the airship’s not very controlled flight appear in the film.

All these interesting and exciting adventures went on in short breaks from Derek’s day job. Lasham was growing, operating efficiently and setting standards. He invented the Piggott Hook, a simple device which does an important job. Too many glider pilots have launched with the airbrakes unlocked. Undetected, they blow open and have caused serious crashes. Derek persuaded a major German manufacturer to fit a Piggott Hook on all their new gliders and many others have been retro-fitted on existing gliders. Derek’s teachings appeared in print. He wrote many articles and no fewer than eight books, one of which is still in print in its eighth edition. There were more diversions.

In 1972, Anglia Television planned a programme to prove that Sir George Cayley’s ‘governable parachute’ could actually have flown over Brompton Vale in 1853. A replica was built by Southdown Aero Services base on the limited information which had been found. The machine had a fixed cruciform tail, which could be adjusted on the ground and the pilot held an ‘influencer’, another smaller tail unit at the end of a moveable pole. Sir George had given a clear description of the wheels, made from laminations of thin ash. In practice they proved remarkably sturdy. They provided little springing and made a terrible noise when rolling down the runway at 30 mph but never broke or gave any trouble during many landings and other arrivals. The machine was tested at Lasham.

Launching was by a car tow and it took some time to get the ‘fixed’ tail properly adjusted. Despite several heavy landings, the wheels cushioned the blows and damage was minor and easily repaired. The influencer was well named. Reactions to its movements were very slow but the glider’s good pendulum stability meant little lateral control was needed. Derek enjoyed the marked contrast between the rattling noise of ground running and the silence of flight, disturbed only by faint whistling of the wires and the flapping of the edges of the sail.

The glider was taken to Brompton Vale in Yorkshire where it was easy to find the place where the original had been launched. The launches, by bungee, went well, the TV company had its programme ’in the can’ and the glider was retired to the RAF Museum.

The glider was taken to Brompton Vale in Yorkshire where it was easy to find the place where the original had been launched. The launches, by bungee, went well, the TV company had its programme ’in the can’ and the glider was retired to the RAF Museum.

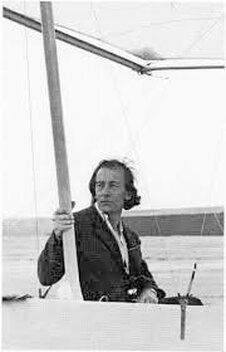

Derek stayed at the helm of Lasham until 1989, when he retired. He was still seen there frequently, just flying for the love of gliding.

In 2003, he flew a Fedorov Me7 glider in a competition. The Me 7 was designed as an ‘affordable’ glider. With a span of only 12.6 its performance cannot match other competition gliders of 15 and 18 metre span. The task was a 500 km (312 miles) distance, enough to qualify for a Diamond on a Gold C badge. Derek completed the task – not bad for an Me 7, or for a man of 81.

He was back again in 2008. Queen Mary University of London college students had fitted an Edgeley Optimist glider with 16 brushless Graupner electric motors. Who better to test it than the man who had flown the original Optimist prototype? He was 86 at the time. Does that make him history’s oldest test pilot?

He gave up flying solo when he was 90. Here he is flying with Roy Cross.

Their combined ages total 171.

Derek Piggott died at the age of 96. He had flown 154 types of powered aircraft and 170 types of glider. He was awarded the MBE for services to gliding. The Royal Aero Club awarded him their Gold Medal – the highest award for aviation in the UK, the Royal Aeronautical Society appointed him an Honorary Companion of the Society and he was awarded the Lilienthal Gliding Medal by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale for outstanding service over many years to the sport of gliding – all honours which were richly deserved.

Their combined ages total 171.

Derek Piggott died at the age of 96. He had flown 154 types of powered aircraft and 170 types of glider. He was awarded the MBE for services to gliding. The Royal Aero Club awarded him their Gold Medal – the highest award for aviation in the UK, the Royal Aeronautical Society appointed him an Honorary Companion of the Society and he was awarded the Lilienthal Gliding Medal by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale for outstanding service over many years to the sport of gliding – all honours which were richly deserved.