Frank Tilley – 617 Squadron (Feb 2018)

Frank was a friend and work colleague of AEG member John Harper. Grateful thanks are due to John for sending us this obituary which was written by Dr Robert Owen, Official Historian of No. 617 Squadron Association. Any augmentation is in italics and the photographs have been tracked down from the internet and ‘Beyond the Dams to the Tirpitz‘ by Alan W Cooper.

Frank Tilley was born in Hackney, London, on Boxing Day 1922, the youngest of 8 children. After education at the Grocer’s Grammar School, Hackney and Hackney Technical College, he joined Dessouter Brothers, in Hendon, manufacturers of artificial limbs. The work did not exactly fire Frank’s enthusiasm. The call for men to join the forces at the outbreak of war seemed to offer an escape route, but it was not to be. Much to Frank’s dismay he discovered that he was in a “reserved” occupation. However, he eventually discovered a loophole – the embargo on his recruitment did not extend to RAF aircrew. So, it was that in early 1943 that Frank presented himself at RAF Cardington as an aspiring aviator. Deterred by the length of training required to become a pilot, he opted for a trade which admirably suited to his engineering aptitude – that of Flight Engineer.

Frank Tilley was born in Hackney, London, on Boxing Day 1922, the youngest of 8 children. After education at the Grocer’s Grammar School, Hackney and Hackney Technical College, he joined Dessouter Brothers, in Hendon, manufacturers of artificial limbs. The work did not exactly fire Frank’s enthusiasm. The call for men to join the forces at the outbreak of war seemed to offer an escape route, but it was not to be. Much to Frank’s dismay he discovered that he was in a “reserved” occupation. However, he eventually discovered a loophole – the embargo on his recruitment did not extend to RAF aircrew. So, it was that in early 1943 that Frank presented himself at RAF Cardington as an aspiring aviator. Deterred by the length of training required to become a pilot, he opted for a trade which admirably suited to his engineering aptitude – that of Flight Engineer.

A few months later he was formally called up and instructed to report to the Aircrew Reception Centre at Lord’s cricket ground in St John’s Wood, before being posted to No. 3 Initial Training Wing at Torquay, where he was introduced to the discipline of service life. After six weeks of lectures on Air Force Law, endless drill and relentless physical education and swimming designed to transform pale civilians into toned fighting men, he was posted to No. 4 School of Technical Training at St Athan, in South Wales in September 1943. Here Frank was taught the intricacies of aircraft engineering and systems; engine management to obtain the most economical fuel consumption and optimum power settings, fuel management to balance the aircraft and reduce the strain on its structure, and a myriad of other technical details necessary to maintain the aircraft systems in the air.

Despite his aircrew status, Frank had yet to experience any form of flying; training was conducted using diagrams and test rigs, graduating to the real thing in the form of the written off aircraft relegated to ground instructional airframes. By March 1944 Frank was deemed sufficiently proficient to become part of a bomber crew. Along with others from his course he was posted to No. 1660 Conversion Unit at Swinderby, Lincs. Here he teamed up with six other young men who had already formed a crew and had been training on Vickers Wellingtons. Now they were about to convert to the Short Stirling, a more complicated machine, necessitating a seventh crew member – the Flight Engineer.

Frank’s in the middle of the back row

Frank’s in the middle of the back row

The crew that Frank joined reflected the cosmopolitan and all-embracing social nature of Bomber Command. The captain Arthur Joplin (‘Joppy’ to the crew) was a 20-year-old clerk from New Zealander, the bomb aimer, Loftus Hebbard, a fellow Kiwi, at 24, the oldest member of the crew. From Lancashire Basil Fish the navigator, had been studying civil engineering at Manchester University, and air gunner Roberton Yates was a classics scholar, the other gunner had been a carder in a woollen mill. Having mastered the Stirling the crew transferred to a so-called “Finishing School” at Syerston, for a week or so of learning to master the machine in which they would go to war, the Avro Lancaster.

At the completion of this course the crew were dumbstruck to learn that they were to be posted to No. 617 Squadron – the “Dambusters” based at Woodhall Spa. This was a special duties squadron, which normally only took on experienced crews who had already survived a tour of 30 operations. However, an experiment was being introduced whereby a few new crews who had demonstrated above average ability were posted directly to the Squadron. It was intended that the newcomers would learn by example and osmosis, in effect being fast tracked to a level of operational expertise.

They arrived on the Squadron in mid-August 1944, at first feeling rather overwhelmed by the propensity of experienced crews and unsure as to how they would be received as a “sprog” crew. Their concern was unfounded. After an initial wariness, they found themselves absorbed into the routine of extensive practice and training in order to achieve the precision for which the Squadron was renowned. It was a steep learning curve, but they found support and encouragement.

The crew’s first operation came a fortnight later, no easy “milk run” but a daylight attack against the heavily defended port at Brest. On this occasion the target was not the reinforced concrete U-boat pens, necessitating the 12,000lb ‘Tallboy’ deep penetration bomb, but various vessels in the harbour attacked with 12 x 1,000lb bombs. All seemed to go well, but they were unable to observe any results owing to smoke and spray.

The crew had insufficient experience to participate in the Squadron’s next operation, their first attack on the German battleship Tirpitz, flown from an advanced base in Russia. For his second operation, Frank found himself as stand in Flight Engineer for Sqn Ldr Drew Wyness for a night attack against the Dortmund Ems Canal. It was a tough operation. Poor weather over the target forced the crew to return with their ‘Tallboy’ – but at several times during the return flight their heavily laden aircraft had to fend off approaching German night fighters. They were fortunate, although one of the Squadron’s aircraft was not so lucky.

They arrived on the Squadron in mid-August 1944, at first feeling rather overwhelmed by the propensity of experienced crews and unsure as to how they would be received as a “sprog” crew. Their concern was unfounded. After an initial wariness, they found themselves absorbed into the routine of extensive practice and training in order to achieve the precision for which the Squadron was renowned. It was a steep learning curve, but they found support and encouragement.

The crew’s first operation came a fortnight later, no easy “milk run” but a daylight attack against the heavily defended port at Brest. On this occasion the target was not the reinforced concrete U-boat pens, necessitating the 12,000lb ‘Tallboy’ deep penetration bomb, but various vessels in the harbour attacked with 12 x 1,000lb bombs. All seemed to go well, but they were unable to observe any results owing to smoke and spray.

The crew had insufficient experience to participate in the Squadron’s next operation, their first attack on the German battleship Tirpitz, flown from an advanced base in Russia. For his second operation, Frank found himself as stand in Flight Engineer for Sqn Ldr Drew Wyness for a night attack against the Dortmund Ems Canal. It was a tough operation. Poor weather over the target forced the crew to return with their ‘Tallboy’ – but at several times during the return flight their heavily laden aircraft had to fend off approaching German night fighters. They were fortunate, although one of the Squadron’s aircraft was not so lucky.

‘Tallboys’ were in extremely short supply, and needed to be conserved whenever possible. A daylight operation to attack the sea wall at Walcheren on 3 October saw the squadron positioned at the end of an attack by other aircraft of Bomber Command. On arrival, the target was seen already to be breached and their bomb was brought home.

Their first opportunity to release this weapon came four days later, during an operation against the Kembs barrage on the River Rhine, near Basle. The attack was to be made in two parts – an initial high-level force to cause confusion and distract the defences, followed by six aircraft coming in along the river at 600 feet. Bombing from 7,500’ in the first wave, the crew reported a very near miss close to the barrage.

Their first opportunity to release this weapon came four days later, during an operation against the Kembs barrage on the River Rhine, near Basle. The attack was to be made in two parts – an initial high-level force to cause confusion and distract the defences, followed by six aircraft coming in along the river at 600 feet. Bombing from 7,500’ in the first wave, the crew reported a very near miss close to the barrage.

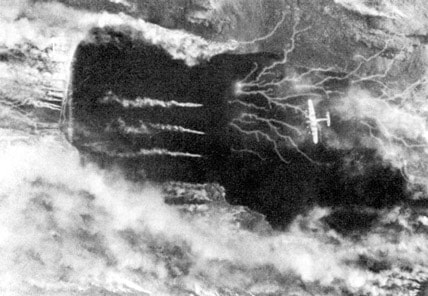

Following the previous attack on the 15th September Tirpitz had been brought south to Tromsø and was now within range of aircraft operating from Scotland. Now a proven crew, their next two operations were directed to finally despatch this vessel. On 29 October, they were part of a force of aircraft from Nos. 9 and 617 Squadrons which detached to Lossiemouth where they refuelled before heading for the Arctic Circle. After a flight of nearly 7 hours they reached their target. The weather was clear, but as the Squadron made their bombing run a layer of low cloud moved in. Despite this, the crew released their ‘Tallboy’, as did some of the other aircraft, but the cloud had prevented accurate aim.

Tirpitz was a threat to the Arctic convoys to Russia and was attacked several times.

22 September 1943 by midget submarines X-5, X-6 and X-7 - damage severe enough for Tirpitz to be out of action for six months.

12 February 1944 by four Soviet bombers - no damage.

3 April 1944 by 40 Barracudas from HMS Victorious and 5 smaller carriers - heavy damage to superstructure. (picture on right)

22 August 1944 by HMS Indefatigable and 4 other carriers - no damage.

24 August 1944 by 33 Barracudas from Indy plus two – 2 hits.

28 August 1944 by 26 Barracudas – no success

15 September 1944 by 27 Lancasters from Yagodnik near Archangel

22 September 1943 by midget submarines X-5, X-6 and X-7 - damage severe enough for Tirpitz to be out of action for six months.

12 February 1944 by four Soviet bombers - no damage.

3 April 1944 by 40 Barracudas from HMS Victorious and 5 smaller carriers - heavy damage to superstructure. (picture on right)

22 August 1944 by HMS Indefatigable and 4 other carriers - no damage.

24 August 1944 by 33 Barracudas from Indy plus two – 2 hits.

28 August 1944 by 26 Barracudas – no success

15 September 1944 by 27 Lancasters from Yagodnik near Archangel

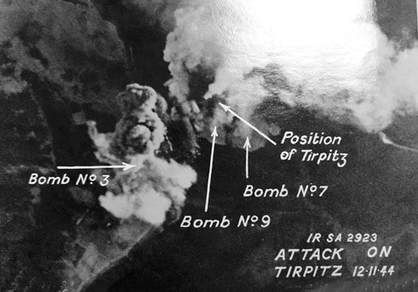

The Tirpitz is under the smoke in the top left hand corner of the picture. One Tallboy hit the bow, penetrated through the ship and exploded on the bottom of the fjord. The damage was severe enough to make the battleship no longer seaworthy. Tirpitz crept south to near Tromsø for repairs to ‘floating battery’ status.

Tromsø was within range of Lossiemouth and the squadrons returned on 12 November. German radar did not detect the approaching bombers and defending fighters were scrambled too late. The leading bomb aimers were able to see the battleship clearly and soon it was surrounded by smoke and spray into which following crews including Frank’s dropped their ‘Tallboys’.

The impressive crater of a not-very-

near miss – was it Bomb No 3?

The impressive crater of a not-very-

near miss – was it Bomb No 3?

By the end of the attack, after at least two hits and several near misses, Tirpitz had rolled over to port, and capsized. There was insufficient depth of water for her to sink beneath the waves, but as the aircraft turned for home sight of her dark red keel confirmed the success of the operation. The long flight home was exacerbated by headwinds and despite Frank’s careful management of fuel and the additional fuel carried it was deemed prudent to land at Sumburgh in the Shetlands to refuel before finally returning to Woodhall.

December saw a return to land based targets, with two attempts, along with other aircraft of Bomber Command, to breach the Urft Dam, near Heimbach. Once again, the weather was against them. On the first attack on 8 December not only was the weather against them, but heavy flak struck their aircraft, forcing them to limp back and put down at the nearest UK airfield, Manston, in Kent. Three days later they tried again, only to see their ‘Tallboy’ overshoot the target.

After one more daylight attack, against the R-boat pens at Ijmuiden the Squadron found themselves detailed on 21 December 1944 for a deep penetration night attack against an oil refinery at Politz, near Stettin (Szczecin) in Poland. For four of the crew, including the pilot, it would be their first night operation over Germany and to make things more difficult there was the expectation of poor weather on return to the UK necessitating possible diversion to other airfields at the end of an eight-hour flight.

The outward flight was uneventful and the crew reached the designated area, but found that the target marking appeared haphazard. After releasing their ‘Tallboy’ against a nominated marker they headed for home, setting course for their designated diversionary base in Scotland, which would have not only the advantage of clear weather, but would also shorten the length of the flight. Soon afterwards the wireless operator reported that they were being ordered to return to Lincolnshire. Although this would stretch their fuel reserves Frank considered it was a viable option and they headed for Woodhall Spa. As they crossed the coast it became apparent that Lincolnshire was still shrouded in fog. A further instruction was received for all aircraft to land at the first available airfield.

It seemed that crew were in luck, for very soon they saw a glow through the murk which was identified as the airfield at Ludford Magna. That this was visible was solely due to the fact that it was one of a small number of airfields equipped with FIDO – using burning petrol to disperse fog on the runway approach enabling aircraft to land in such conditions. Joppy homed in on the glow and circled, calling up and asking permission to land. There was no reply. The crew were now in a perilous position. Other aircraft would also be circling, increasing the risk of collision, and Frank reported that their fuel state prevented diversion to any fog free airfield.

They needed to land as soon as possible and were also aware of the rising ground of the Lincolnshire Wolds beneath. A few minutes later, while still circling, a sudden shudder ran through the aircraft as the port wing brushed a hillside. Looking out past his pilot, Frank was seemingly aware of the wing beyond the outer engine bending upwards. Joppy immediately called for more power and Frank responded by pushing the throttles forward. The aircraft was still airborne, but only just, and would not remain so for long. There was a further bump, a horrendous noise and violent shaking – then everything became still.

Frank looked back and saw that the cockpit and nose had broken off from the main fuselage. The wreckage was on fire and Basil Fish, the navigator, had been knocked unconscious. Frank shouted to him to get out. He tried to get clear himself but found that he could hardly stand. With great effort, he crawled and dragged himself away from the cockpit and to relative safety. Looking around, he saw Basil removing smouldering flying kit from the wireless operator before heading back to the blazing wreckage to rescue Joppy who was trapped in his seat. This done, Basil went back in an effort to locate other members of the crew, but the heat of the flames drove him away.

Realising that he was the least injured and the only one of five survivors with any degree of mobility Basil set off across the fields in search of assistance, having briefed Frank to listen out for a series of whistle blasts that would signal his return. Nearly three hours later Frank heard a whistle, and sounded his own in reply to guide the rescuers to the injured.

Frank was admitted to the RAF Hospital at Rauceby with a broken leg and severe bruising to the other. Considering that he was not strapped in at the time of the crash since his role as flight engineer required him to stand for much of the time next to the pilot, or perch on a rudimentary canvas sling seat, he was incredibly fortunate not to be far more severely injured.

After one more daylight attack, against the R-boat pens at Ijmuiden the Squadron found themselves detailed on 21 December 1944 for a deep penetration night attack against an oil refinery at Politz, near Stettin (Szczecin) in Poland. For four of the crew, including the pilot, it would be their first night operation over Germany and to make things more difficult there was the expectation of poor weather on return to the UK necessitating possible diversion to other airfields at the end of an eight-hour flight.

The outward flight was uneventful and the crew reached the designated area, but found that the target marking appeared haphazard. After releasing their ‘Tallboy’ against a nominated marker they headed for home, setting course for their designated diversionary base in Scotland, which would have not only the advantage of clear weather, but would also shorten the length of the flight. Soon afterwards the wireless operator reported that they were being ordered to return to Lincolnshire. Although this would stretch their fuel reserves Frank considered it was a viable option and they headed for Woodhall Spa. As they crossed the coast it became apparent that Lincolnshire was still shrouded in fog. A further instruction was received for all aircraft to land at the first available airfield.

It seemed that crew were in luck, for very soon they saw a glow through the murk which was identified as the airfield at Ludford Magna. That this was visible was solely due to the fact that it was one of a small number of airfields equipped with FIDO – using burning petrol to disperse fog on the runway approach enabling aircraft to land in such conditions. Joppy homed in on the glow and circled, calling up and asking permission to land. There was no reply. The crew were now in a perilous position. Other aircraft would also be circling, increasing the risk of collision, and Frank reported that their fuel state prevented diversion to any fog free airfield.

They needed to land as soon as possible and were also aware of the rising ground of the Lincolnshire Wolds beneath. A few minutes later, while still circling, a sudden shudder ran through the aircraft as the port wing brushed a hillside. Looking out past his pilot, Frank was seemingly aware of the wing beyond the outer engine bending upwards. Joppy immediately called for more power and Frank responded by pushing the throttles forward. The aircraft was still airborne, but only just, and would not remain so for long. There was a further bump, a horrendous noise and violent shaking – then everything became still.

Frank looked back and saw that the cockpit and nose had broken off from the main fuselage. The wreckage was on fire and Basil Fish, the navigator, had been knocked unconscious. Frank shouted to him to get out. He tried to get clear himself but found that he could hardly stand. With great effort, he crawled and dragged himself away from the cockpit and to relative safety. Looking around, he saw Basil removing smouldering flying kit from the wireless operator before heading back to the blazing wreckage to rescue Joppy who was trapped in his seat. This done, Basil went back in an effort to locate other members of the crew, but the heat of the flames drove him away.

Realising that he was the least injured and the only one of five survivors with any degree of mobility Basil set off across the fields in search of assistance, having briefed Frank to listen out for a series of whistle blasts that would signal his return. Nearly three hours later Frank heard a whistle, and sounded his own in reply to guide the rescuers to the injured.

Frank was admitted to the RAF Hospital at Rauceby with a broken leg and severe bruising to the other. Considering that he was not strapped in at the time of the crash since his role as flight engineer required him to stand for much of the time next to the pilot, or perch on a rudimentary canvas sling seat, he was incredibly fortunate not to be far more severely injured.

Clockwise from top left - Flt Sgt Basil Fish, navigator, who went for help, Flt Sgt Hebbard (off sick at the time – replaced as bomb aimer by Fg Off Arthur Walker who died in the crash), Sgt Frank Tilley, broken leg, Fg Off Bob Yates, mid-upper gunner, died, Sgt Norman Lambell DFM, rear gunner, not with the crew, having been replaced by James Thompson who suffered severe back injuries, Fg Off Arthur Joplin multiple leg fractures, Sgt Gordon Cooke, wrist and internal injuries.

As his condition improved, Frank was sent to Hoylake for convalescence before returning to Woodhall Spa in August 1945. By now the European war was over, and following VJ Day Frank was keen to return to civilian life. However, it would be another eighteen months until this could be achieved, during which Frank re-mustered to a clerical role, serving with Polish units operating in Transport Command. He finally left the Service in February 1947. (Later in the same year, he and June were married. He told her nothing about his wartime experiences until 40 years later).

Frank commenced a new career with the National Cash Register Company, which eventually led him into the world of computing. He retired as Worldwide Technical Services Manager for ICL in 1982.

The fame of the Dambusters lived on after the war and Frank was involved in many reunions. He was one of the steadily decreasing number of survivors who were helpful to John Nicol in writing his book ‘After the Flood –What the Dambusters Did Next’.

Frank commenced a new career with the National Cash Register Company, which eventually led him into the world of computing. He retired as Worldwide Technical Services Manager for ICL in 1982.

The fame of the Dambusters lived on after the war and Frank was involved in many reunions. He was one of the steadily decreasing number of survivors who were helpful to John Nicol in writing his book ‘After the Flood –What the Dambusters Did Next’.