Boeing’s Stratocruiser (Sept 2019)

The Second World War ended with a bang – well, two bangs. Suddenly, no-one needed all the military equipment, vehicles and aeroplanes being produced for the expected invasion of Japan. Makers of fighters and bombers prepared to close down their existing production lines and looked to the civilian market to stay in business.

Lockheed were already building the Constellation which could carry 44 passengers in pressurised comfort and which Howard Hughes was eager to use in TWA colours. Douglas were making the DC-4 which seemed to be the natural choice. It could easily be converted to carry paying passengers. Boeing were in a more difficult position. Having concentrated on bombers, they had supplied thousands of Fortresses and Superfortresses to the USAAF. It was back in 1935 when they designed their last airliner, admittedly based on the B-17. It was a forward looking design with the first pressurised fuselage, but the war had killed off any further development and only 10 were built.

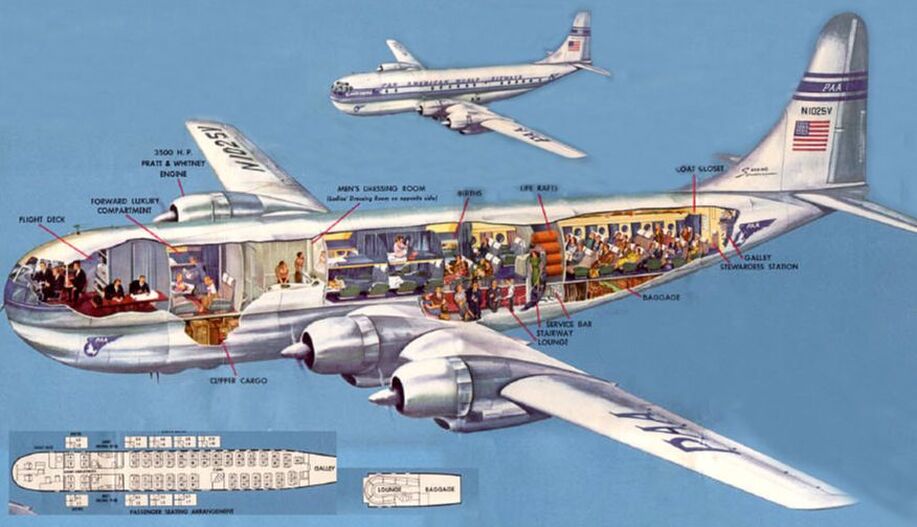

In 1942 Boeing proposed to fit a larger fuselage to the B-29 and offer it to the military as a transport. The bigger cross-sectioned body did not replace the B-29 fuselage. It effectively sat on top of it, making a ‘double-bubble’ fuselage. The USAAF ordered three prototype Stratofreighters for evaluation. They were tested in 1945 and, in July, ten were ordered for service testing.

At about this time, Boeing had a newly appointed President. William Allen was not an engineer. He had worked with the company for some years, always as a lawyer. So when offered the job he was, at first, reluctant to take it. Now, he accepted the responsibility and, without any order from civilian customers, decided to build 50 of the freighters as airliners, now named Stratocruisers. He accepted that they would be more expensive that the competition (DC-4 and Constellation) so ordered that they should have the most luxurious fittings possible.

His bet paid off. On 29 November 1945, Pan Am ordered 20 – a $24,500,000 order.

The first flight of the prototype was on 8 July 1947 but its entry into service was delayed for over a year. The CAA didn’t like the stalling characteristics when they found that the stall was sudden and a wing was liable to drop. They insisted on spoilers being fitted to the leading edges of the wing between the engines and the fuselage to ensure that the stall was more progressive and the nose would drop first. Ironically, there was little likelihood of the aeroplane stalling when it was flying at its slowest i.e. on the approach to land. The wing was fitted to the fuselage at a relatively high angle of incidence so when the pilot flared for landing the nose didn’t rise enough to keep the nose wheel off the ground.

The pilots quickly became accustomed to doing ‘wheelbarrow’ landings. This rather grainy photograph is taken from a video but shows clearly that the Stratocruiser is landing nose wheel first.

Pan American were the first users of the Stratocruiser and made much of the luxurious element of their service. Certainly it appealed to the people who could afford air travel at that time. Pan Am introduced a scheduled service from San Francisco to Honolulu, BOAC flew a trans-Atlantic service, with refuelling stops, United and Northwest Orient flew internal services and also to Hawaii. Whilst the aeroplane proved popular with passengers it was expensive to operate. Maintenance costs were high, primarily because of the power plants.

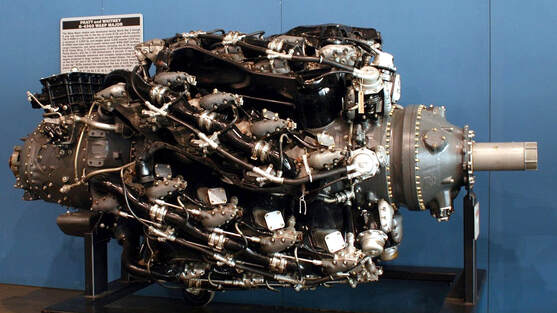

The Stratocruisers were fitted with four Pratt and Whitney R-4360-B6 Wasp Major supercharged piston engines developing 3,500 hp each. The four-rows of 7 radial cylinders had 56 manually-adjustable valves and 56 spark plugs, all of which could be fouled if there was a false start. The engines drove Curtis Electric or Hamilton Standard four-blade constant-speed fully feathering and braking airscrews.

It was an over-speeding propeller which caused the first loss of Stratocruiser passengers in April 1952. The unbalanced forces broke the whole engine away from the wing and the aircraft disintegrated and fell into the Brazilian jungle, killing all 50 aboard.

Another engine was lost in March 1955 but the pilot was able to retain control and ditch the aircraft in the sea 35 miles off the coast of Oregon. 19 of the 23 people on board were rescued. It was the mis-handling of the engine cowl flaps that led to another ditching in April 1956. 5 people died.

The accident which is most comprehensively recorded occurred on 16 October 1956. Pan Am had scheduled a round-the-world flight flying eastbound from Philadelphia to Europe, Asia, and sundry Pacific Islands. The last leg was from Honolulu to San Francisco and Clipper Sovereign of the Skies took off for the 9 hour flight carrying a crew of 7 and 24 passengers, three of whom were infants. At about the half way point they planned to climb to 21,000 ft. Captain Richard Ogg was at the navigation table and First Officer George Haaker was flying the aircraft. When they reached 21,000 ft Haaker levelled the Stratocruiser and reduced the power.

At that moment, they heard, in Ogg’s words, ‘the sudden, rising, deafening scream of a propeller running far past normal speeds’. It was Number 1 engine, the port outer, and when Ogg got back to his seat Haaker was already pressing the button to feather the prop. It was totally ineffective.

Ogg slowed the aircraft to 140 knots to try to reduce the speed of the propeller and told the flight engineer to cut off the oil supply to the engine. It was a harsh way to stop the engine and within three minutes it seized with a thud which shook the aircraft. The propeller shaft broke and the prop continued windmilling freely.

They assessed their situation and Ogg had the passengers moved away from the seats in line with the propeller in case it should fly off and penetrate the fuselage. They could increase power on the other engines to overcome the drag of No 1’s prop but that would increase the fuel consumption and they would be highly unlikely to reach land. Ogg knew he was going to have to ditch in the sea.

Fortunately, they were within 40 miles of the ocean station of the Pontchartrain, a US Coastguard cutter. (This was in the pre-satellite days when weather forecasters relied heavily on weather reports from ships at sea and the Coastguard positioned their ships conveniently for this purpose and for providing rescue and assistance for any shipping). Ogg was in radio contact with the Pontchartrain when the Stratocruiser yawed to starboard. No 4 engine was failing. They were now losing height and Ogg turned towards the ship’s position. He spoke to the passengers and explained everything to them and told the cabin staff to rehearse the emergency drill.

All this was done in the darkness of the night. On the Pontchartrain the crew swung out two motorboats ready for launching and prepared to lay a line of floating lights along the landing path. In another stroke of good fortune the crew had rehearsed this very drill just two months before. They also lit every light on the ship so that the passengers in the circling Stratocruiser could see them. As fuel was used up and the aircraft became lighter and height could maintain on two engines. Ogg resolved to wait until dawn before ditching.

By 0730 it was full daylight but Ogg still circled to use up as much fuel as possible. He continued chatting to the passengers so that they knew exactly what was happening. They responded well. They remained calm and there was no sign of panic throughout during the five long hours between the original propeller failure and the ditching.

Another engine was lost in March 1955 but the pilot was able to retain control and ditch the aircraft in the sea 35 miles off the coast of Oregon. 19 of the 23 people on board were rescued. It was the mis-handling of the engine cowl flaps that led to another ditching in April 1956. 5 people died.

The accident which is most comprehensively recorded occurred on 16 October 1956. Pan Am had scheduled a round-the-world flight flying eastbound from Philadelphia to Europe, Asia, and sundry Pacific Islands. The last leg was from Honolulu to San Francisco and Clipper Sovereign of the Skies took off for the 9 hour flight carrying a crew of 7 and 24 passengers, three of whom were infants. At about the half way point they planned to climb to 21,000 ft. Captain Richard Ogg was at the navigation table and First Officer George Haaker was flying the aircraft. When they reached 21,000 ft Haaker levelled the Stratocruiser and reduced the power.

At that moment, they heard, in Ogg’s words, ‘the sudden, rising, deafening scream of a propeller running far past normal speeds’. It was Number 1 engine, the port outer, and when Ogg got back to his seat Haaker was already pressing the button to feather the prop. It was totally ineffective.

Ogg slowed the aircraft to 140 knots to try to reduce the speed of the propeller and told the flight engineer to cut off the oil supply to the engine. It was a harsh way to stop the engine and within three minutes it seized with a thud which shook the aircraft. The propeller shaft broke and the prop continued windmilling freely.

They assessed their situation and Ogg had the passengers moved away from the seats in line with the propeller in case it should fly off and penetrate the fuselage. They could increase power on the other engines to overcome the drag of No 1’s prop but that would increase the fuel consumption and they would be highly unlikely to reach land. Ogg knew he was going to have to ditch in the sea.

Fortunately, they were within 40 miles of the ocean station of the Pontchartrain, a US Coastguard cutter. (This was in the pre-satellite days when weather forecasters relied heavily on weather reports from ships at sea and the Coastguard positioned their ships conveniently for this purpose and for providing rescue and assistance for any shipping). Ogg was in radio contact with the Pontchartrain when the Stratocruiser yawed to starboard. No 4 engine was failing. They were now losing height and Ogg turned towards the ship’s position. He spoke to the passengers and explained everything to them and told the cabin staff to rehearse the emergency drill.

All this was done in the darkness of the night. On the Pontchartrain the crew swung out two motorboats ready for launching and prepared to lay a line of floating lights along the landing path. In another stroke of good fortune the crew had rehearsed this very drill just two months before. They also lit every light on the ship so that the passengers in the circling Stratocruiser could see them. As fuel was used up and the aircraft became lighter and height could maintain on two engines. Ogg resolved to wait until dawn before ditching.

By 0730 it was full daylight but Ogg still circled to use up as much fuel as possible. He continued chatting to the passengers so that they knew exactly what was happening. They responded well. They remained calm and there was no sign of panic throughout during the five long hours between the original propeller failure and the ditching.

The time came at 0810. The sea was remarkably calm with little swell and Ogg approached at 90 knots, flaps down and undercarriage up. He expected the aircraft to bounce but as it hit the water it dug in. The nose went under but then it lifted and the Stratocruiser floated on the surface. The tail had broken off but Ogg had anticipated this and had moved all the passengers forward to the centre section.

Apart from a few bruises and seat belt squeezes no one was seriously hurt. Two 2-year old twin girls had been held by their parents. One lost his grip and little Maureen was catapulted into a bulkhead but it was a short distance and she seemed to be unharmed.

The life rafts were pushed out of the exits and inflated. Within four minutes, everyone was safely in the rafts and Capt Ogg went back inside to check that it was all clear. They then transferred to the boats and to the ship.

The wreckage floated for nearly 20 minutes allowing some of the Pontchartrain’s crew to collect items of floating luggage and even some from inside the cabin.

On board the ship, everyone was able to have a shower, the senior ship’s officers gave up their cabins and somehow all 31 of the survivors were fitted into an available space. The Pontchartrain was ordered to leave its station and proceed to San Francisco. The lily of this perfectly handled rescue was gilded as they sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge. They were met by another Coastguard cutter which handed over 31 suitcases, each carrying the name of a passenger or crew member. Inside were new sets of clothing, all correctly sized to match the recipient.

Not all accidents had such a happy outcome. During their service from 1951 to 1961 out of 55 Stratocruisers built 13 crashed or were lost and 139 people died. Nevertheless, they carried thousands of very satisfied passengers millions of miles and they were phased out, not because of their record, but because of the introduction of Boeing’s own 707, Douglas’s DC-8 and the DH Comet.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Not all accidents had such a happy outcome. During their service from 1951 to 1961 out of 55 Stratocruisers built 13 crashed or were lost and 139 people died. Nevertheless, they carried thousands of very satisfied passengers millions of miles and they were phased out, not because of their record, but because of the introduction of Boeing’s own 707, Douglas’s DC-8 and the DH Comet.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

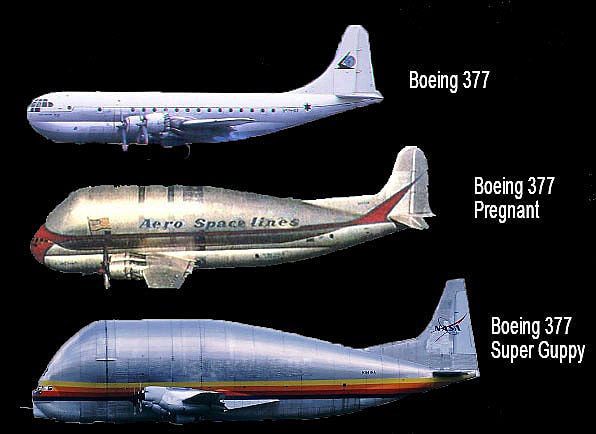

The heart of the Stratocruiser lives on and all because of an ex-B-17 pilot. In 1960 Jack Conroy learned that parts of the rockets for NASA’s space programme were being built in California and taken to Florida via the Panama canal. He dreamed up a modification for one of the Stratocruisers, which were being retired, to allow it to carry a rocket. He took the idea to NASA but they weren’t impressed, apart from Werner von Braun, who thought it might just work.

Conroy mortgaged his house, bought an old Pan Am Stratocruiser and fitted the upper body of an old BOAC model on top of it. It flew in September 1962 and Conroy showed it off to an, initially, sceptical audience. They were delighted (von Braun insisted on flying in it himself) and the Pregnant Guppy came into active service.

Conroy mortgaged his house, bought an old Pan Am Stratocruiser and fitted the upper body of an old BOAC model on top of it. It flew in September 1962 and Conroy showed it off to an, initially, sceptical audience. They were delighted (von Braun insisted on flying in it himself) and the Pregnant Guppy came into active service.

It was followed by the Super Guppy and the Mini Guppy (both with turbo-prop engines). They were even used by Airbus until its own Beluga was built (sincere flattery?).

So the Stratocruiser, despite its problems, founded a dynasty which is still alive today.