Clouston and the Comet (Oct 15)

Arthur Clouston was one of the first civilians employed as a test pilot at Farnborough. A New Zealander, he had previously served four years in the RAF. Alongside his work for the Air Ministry he flew his own Aeronca C.3 and became interested in air racing. He entered several local races with varying success. Then he was tempted by the much greater challenge of the Schlessinger race from England to Johannesburg with a £4000 prize for the winner. Needing a better aeroplane he managed to find a second hand Miles Hawk. Backed by F. E. Tasker, a London Aeroplane Club member, he entered the race. Only one competitor reached Johannesburg. Clouston battled with engine problems and forced landings before his final crash just 400 miles from the finish. He was broke, but he had learned a tremendous amount about the preparations and problems of long distance racing.

In 1937, the French celebrated the 10th anniversary of Lindbergh’s trans-Atlantic flight to Paris by organising a race to Damascus and return to Paris. Clouston was keen to enter. In a scrapyard, he found the wreck of the MacRobertson race-winning Comet. After the race it had been bought by the Air Ministry and briefly wore RAF roundels. Clouston had flown it at Farnborough and had been impressed by its performance and efficiency. During full load testing (by another pilot) it crashed and was considered too badly damaged to be repaired. The wreckage was sold to the scrap merchant.

Coulston put down £5 as deposit and persuaded F.E. Tasker to stump up the £245 balance and let him use it for racing. They had the wreck rebuilt by Jack Cross (who later performed his magic on Alex Henshaw’s Mew Gull). Clouston and George Nelson, his co-pilot, flew to Istres, near Marseilles, for the start of the race. Without sponsors, they named the Comet ‘The Orphan’. They were up against stiff competition.

The French air force entered five different types and the Italians had no fewer than six immaculate and fully equipped Savoia Marchetti SM 79 bombers, each with a crew of four. Although the Comet was last to take off when they reached Damascus only one Savoia had landed and a second was overshooting to run off the runway into the desert. They refuelled and with high hopes took off into a clear sky and set course for Paris in perfect visibility. It did not last.

Approaching Vienna the sky ahead was packed with towering dark clouds completely obscuring the Alps. Coulston climbed and at 19000 feet, without heating or oxygen, they were still in cloud. Hail followed rain and ice formed on the wings and blocked the pitot head. Then the ailerons began to freeze up and the engines lost power. They glided down waiting for the crash and at 13000 feet flew into clear air. But they were hemmed in on all sides by the turbulent cloud. As the ice broke off the engines regained power. They were still below the peaks of the higher mountains so they stayed in the clear air, spiralling upwards.

At 17000 feet the clouds closed in and they flew into a snowstorm. Soon the cycle repeated itself – icing, stiff ailerons, power loss and the downward spiral. Suddenly, there was an explosion. It was not the feared crash into a mountainside because the aeroplane was still flying. The canopy and windscreen had shattered. At 11,000 feet the engines came back to life and they climbed again to 17000 feet, heads ducked down against the instrument panels.

Twenty minutes later, the snow increased and the rough running engines signalled a third blind descent. At 8,500 feet, as the power returned, Clouston caught sight of the rocky floor of a valley, a few hundred feet below. Twisting and turning, he followed the valley down until suddenly, they were free of the mountains and the skies were clearing.

When they reached Paris they saw three neatly parked Savoias with their crews being congratulated. There were no other finishers. They had won no prize but were intensely thankful to be there at all. Clouston always considered the flight in the Comet across the Alps to be his worst experience in a lifetime of flying.

Twenty minutes later, the snow increased and the rough running engines signalled a third blind descent. At 8,500 feet, as the power returned, Clouston caught sight of the rocky floor of a valley, a few hundred feet below. Twisting and turning, he followed the valley down until suddenly, they were free of the mountains and the skies were clearing.

When they reached Paris they saw three neatly parked Savoias with their crews being congratulated. There were no other finishers. They had won no prize but were intensely thankful to be there at all. Clouston always considered the flight in the Comet across the Alps to be his worst experience in a lifetime of flying.

Clouston was introduced by a friend to Betty Kirby-Green. A keen pilot with a brand new licence, she had flown to Paris and back for a bet. She had grand ideas for involving Clouston in a trans-Atlantic flight. However, after his failure in the Schlessinger race he had his eyes set on the South Africa record. F E Tasker, the Comet’s owner, who had so far earned nothing in prize money, allowed Clouston to use the aeroplane only if the hire fee was paid in full and in advance. This, plus insurance, fuel and equipment would cost around £2000. Betty said she would raise the money.

She got some sponsorship from Burberry. The Comet got a new name and was painted ‘Burberry beige’. All preparations were made and they were enjoying a farewell dinner at Croydon when Tasker turned up. ‘The flight’s off’, he said, ‘I’m still owed £50’. Betty rushed off to London and came back with just £35. ‘Pass the hat round’ someone called. They did and Tasker left with his money.

They took off for Cape Town on 14 November 1937. The flight went well. They returned to Croydon in 5 days, 17 hours and 30 minutes breaking all existing records. Clouston escaped from the post-race round of dinners and speeches as soon as he could. The award of the Seagrave Trophy and the Royal Aero Club’s Britannia Trophy were much more appreciated.

She got some sponsorship from Burberry. The Comet got a new name and was painted ‘Burberry beige’. All preparations were made and they were enjoying a farewell dinner at Croydon when Tasker turned up. ‘The flight’s off’, he said, ‘I’m still owed £50’. Betty rushed off to London and came back with just £35. ‘Pass the hat round’ someone called. They did and Tasker left with his money.

They took off for Cape Town on 14 November 1937. The flight went well. They returned to Croydon in 5 days, 17 hours and 30 minutes breaking all existing records. Clouston escaped from the post-race round of dinners and speeches as soon as he could. The award of the Seagrave Trophy and the Royal Aero Club’s Britannia Trophy were much more appreciated.

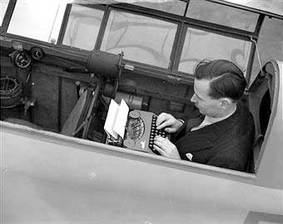

A month later Clouston was on his honeymoon when he received a letter from Victor Ricketts, the air correspondent of the Daily Express. He offered to get sufficient backing for a record-breaking flight to Australia provided he, Ricketts, could go as second pilot. It was too tempting. Clouston wanted to extend the flight to his home in New Zealand but Tasker refused to hire out the Comet for this. Jack Cross overhauled the aeroplane and fitted a small typewriter for Ricketts to use in the rear cockpit. The sponsorship came from the Australian press and the Comet was named Australian Anniversary in honour of the 150th anniversary of the country’s foundation.

The take off from Gravesend was planned for 6 February 1938 with the first stop in Aleppo, Syria. Navigation was not easy because of extensive cloud cover and over Turkey they ran into snow. Too much fuel had been burnt and Clouston thought they had insufficient to reach Aleppo. He turned south towards Adana on the coast where there was an airfield. It was hard to find because it had been recently bulldozed and looked very muddy. Landing as slowly as the Comet would allow they ploughed through the mud which dragged at the wheels. The tail rose and the Comet teetered on its nose then the tail fell back and buried itself in the mud. When they tried to walk away, their boots remained in the sticky mud.

A policeman arrived, put a guard on the plane and they left, by donkey cart, for Adana where they were arrested for not having the correct permission to fly over Turkey. The next day it took two tractors and a train of camels to pull the Comet out of the mud onto a nearby road. Somehow, without any common language, they persuaded an agent to put 50 gallons of fuel into the Comet. That night, they slipped out of the hotel past the sleeping guard and went to the Comet, whose guard was nowhere to be seen. Clouston estimated that there was a distance of about 400 yards of clear road between two bridges which could be enough for the lightly loaded Comet.

A policeman arrived, put a guard on the plane and they left, by donkey cart, for Adana where they were arrested for not having the correct permission to fly over Turkey. The next day it took two tractors and a train of camels to pull the Comet out of the mud onto a nearby road. Somehow, without any common language, they persuaded an agent to put 50 gallons of fuel into the Comet. That night, they slipped out of the hotel past the sleeping guard and went to the Comet, whose guard was nowhere to be seen. Clouston estimated that there was a distance of about 400 yards of clear road between two bridges which could be enough for the lightly loaded Comet.

It was – just. Clouston pulled the Comet off the ground at the last second. One wheel hit the bridge with a crash but they climbed slowly away. When the undercarriage was wound up, the port wheel was left dangling. Victor Ricketts remembered writing an article about a new airfield which had been built in Cyprus so they headed in that direction. Despite the article, the nearest thing they could find that looked like an airfield was a large unfenced piece of ground. Clouston landed carefully and the Comet seemed to be running well on two wheels. As the tail came down, the port wheel folded.

There was a rapid exchange of cables with England. Three days later Alex Henshaw flew to Cyprus in a Vega Gull bringing Jack Cross, tools and equipment. After two weeks work the Comet was flown home.

There was a rapid exchange of cables with England. Three days later Alex Henshaw flew to Cyprus in a Vega Gull bringing Jack Cross, tools and equipment. After two weeks work the Comet was flown home.

The sponsors wanted Clouston to try again. Jack Cross rebuilt the undercarriage and checked the fuel system. All was ready for the second departure time on the night of 15 March 1938. They had breakfast in Cairo and left for Basra, taking the direct route across Saudi Arabia. In the middle of the desert, they ran into a snowstorm. It was the first of a sequence of turbulent cu-nims.

Navigation became difficult and they were forced to make an extra stop at Penang. When they finally arrived at Darwin they were three hours behind Scott and Campbell Black’s record. After a short sleep they flew on in a more relaxed mood to Charleville and Sydney.

Navigation became difficult and they were forced to make an extra stop at Penang. When they finally arrived at Darwin they were three hours behind Scott and Campbell Black’s record. After a short sleep they flew on in a more relaxed mood to Charleville and Sydney.

The thousands of people on the airfield and the rapturous welcome surprised them. It was some time before they realised that they had broken the London – Sydney record by several days. Although they were scheduled to leave on the return flight to London Clouston was determined to fly on to New Zealand. Their sponsors arranged the necessary insurance and they headed east across the Tasman Sea.

When Clouston arrived in Blenheim it had been eighteen years since he had left there for England. There was a night of celebration with his family and the next day he took off again on the long return flight.

When Clouston arrived in Blenheim it had been eighteen years since he had left there for England. There was a night of celebration with his family and the next day he took off again on the long return flight.

The flight back to England was planned with slightly shorter legs but that meant more stops and little time for any rest. They returned to the usual welcoming crowds, speeches and press questions, hardly aware of what was happening. The flight to New Zealand and back had taken just a couple of hours short of eleven days. In that time, they had managed only 16 hours sleep. Clouston and the Comet had broken no fewer than eleven records.

It was not quite the end of his connection with the Comet. He was back at work at Farnborough when he was approached and asked if would use the Comet for a 'special flight'. The Comet would be modified to disguise its identity and Clouston would fly from a secret airstrip in NE England to the Baltic and then head for Berlin from the north east. Timed to coincide with a ceremonial parade the bombs fitted to the Comet would be dropped on Adolf Hitler to ensure that he was killed. Coulston would then fly back to England or to another airfield in Sweden. A payment of a million pounds was offered. Clouston was staggered by this impractical and farcical proposal, although it was deadly serious and made by a man of some standing in public life. He rejected it, of course, but couldn’t help speculating on the outcome if the famous Comet had made an even greater mark on history.

It was not quite the end of his connection with the Comet. He was back at work at Farnborough when he was approached and asked if would use the Comet for a 'special flight'. The Comet would be modified to disguise its identity and Clouston would fly from a secret airstrip in NE England to the Baltic and then head for Berlin from the north east. Timed to coincide with a ceremonial parade the bombs fitted to the Comet would be dropped on Adolf Hitler to ensure that he was killed. Coulston would then fly back to England or to another airfield in Sweden. A payment of a million pounds was offered. Clouston was staggered by this impractical and farcical proposal, although it was deadly serious and made by a man of some standing in public life. He rejected it, of course, but couldn’t help speculating on the outcome if the famous Comet had made an even greater mark on history.