The 1923 Light Aeroplane Competition (Sept 2020)

The Gliding Competition in 1922, initiated by the Daily Mail, might have be fun but it progressed the cause of aviation not one whit. In 1923, the Duke of Sutherland thought he had a better idea. The Duke happened to be the President of the Air League of the British Empire and also Vice-President of the Royal Aero Club. It might have been because of wearing these hats that he collected yet another title. In the summer of 1923 he was appointed by the Government to be Under Secretary of State for Air. With the authority of his new office he immediately announced his competition for ‘low-powered aeroplanes’.

The rules were to be drawn up by the Royal Aero Club and the Air Ministry – the prize would be a modest £500. The Daily Mail promptly overshadowed that by offering a prize of £1000. Confusion over which was ‘first’ prize and which ‘second’ was resolved by limiting the Ministry prize to British competitors whilst the Mail’s money was for the whole world. The Abdulla Company, who made up-market cigarettes, offered £500 for the fastest speed over a two lap course. The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders chipped in with £150 for the greatest number of laps and a similar amount was offered by the British Cycle and Motor Cycle Manufacturers’ and Traders’ Union for the longest distance – provided it was at least 400 miles. Sir Charles Wakefield, who sold Castrol Oil, came up with £200 for the greatest height. Finally the originator of the whole thing, the Duke himself, threw in another £100 for ‘the best landing run’. This was defined as the shortest ‘pulling up’, an odd way to define a landing run.

In the publicity for the contest the Daily Mail began calling it ‘The Motor-Glider Competition’, a newly-coined word which didn’t sit well with the other prize presenters or indeed with most of the entrants. Very few of the competing aeroplanes looked anything like a glider.

The rules emerged. Engine capacity was limited to a miserly 750 cc, although that could be supplemented by the ‘pilot’s own muscular exertions’. The aeroplane would have to be folded, or dismantled, and in a reasonable time, manhandled by not more than two men over a one mile course of field and road, finally passing through a ten foot wide gate. Flying tests would be measured by the most number of laps of a 12½ mile triangular course that could be covered on one gallon of petrol. An important concession was that competing aeroplanes were not required to have a Certificate of Airworthiness for flying in the contest and to and from Lympne, where the trials were to be held.

Unlike 1922, there were few entrants from the ‘lunatic fringe’ and it is interesting to compare the designs which were produced by some who would in time become major manufacturers and designers of well known and successful aeroplanes in later years.

By the first day of the contest 23 British entrants turned up and there were two from France and two from Belgium. The first day was windless but as the week progressed the weather worsened - it was October. The gusty winds degraded many performances and prevented some tests from being carried out. All pilots suffered from engine problems. There was no small engine built for aeroplanes and so most competitors were obliged to use modified motor cycle engine which were unsuited for continuous running at high revs.

Here are some of the competitors.

The rules were to be drawn up by the Royal Aero Club and the Air Ministry – the prize would be a modest £500. The Daily Mail promptly overshadowed that by offering a prize of £1000. Confusion over which was ‘first’ prize and which ‘second’ was resolved by limiting the Ministry prize to British competitors whilst the Mail’s money was for the whole world. The Abdulla Company, who made up-market cigarettes, offered £500 for the fastest speed over a two lap course. The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders chipped in with £150 for the greatest number of laps and a similar amount was offered by the British Cycle and Motor Cycle Manufacturers’ and Traders’ Union for the longest distance – provided it was at least 400 miles. Sir Charles Wakefield, who sold Castrol Oil, came up with £200 for the greatest height. Finally the originator of the whole thing, the Duke himself, threw in another £100 for ‘the best landing run’. This was defined as the shortest ‘pulling up’, an odd way to define a landing run.

In the publicity for the contest the Daily Mail began calling it ‘The Motor-Glider Competition’, a newly-coined word which didn’t sit well with the other prize presenters or indeed with most of the entrants. Very few of the competing aeroplanes looked anything like a glider.

The rules emerged. Engine capacity was limited to a miserly 750 cc, although that could be supplemented by the ‘pilot’s own muscular exertions’. The aeroplane would have to be folded, or dismantled, and in a reasonable time, manhandled by not more than two men over a one mile course of field and road, finally passing through a ten foot wide gate. Flying tests would be measured by the most number of laps of a 12½ mile triangular course that could be covered on one gallon of petrol. An important concession was that competing aeroplanes were not required to have a Certificate of Airworthiness for flying in the contest and to and from Lympne, where the trials were to be held.

Unlike 1922, there were few entrants from the ‘lunatic fringe’ and it is interesting to compare the designs which were produced by some who would in time become major manufacturers and designers of well known and successful aeroplanes in later years.

By the first day of the contest 23 British entrants turned up and there were two from France and two from Belgium. The first day was windless but as the week progressed the weather worsened - it was October. The gusty winds degraded many performances and prevented some tests from being carried out. All pilots suffered from engine problems. There was no small engine built for aeroplanes and so most competitors were obliged to use modified motor cycle engine which were unsuited for continuous running at high revs.

Here are some of the competitors.

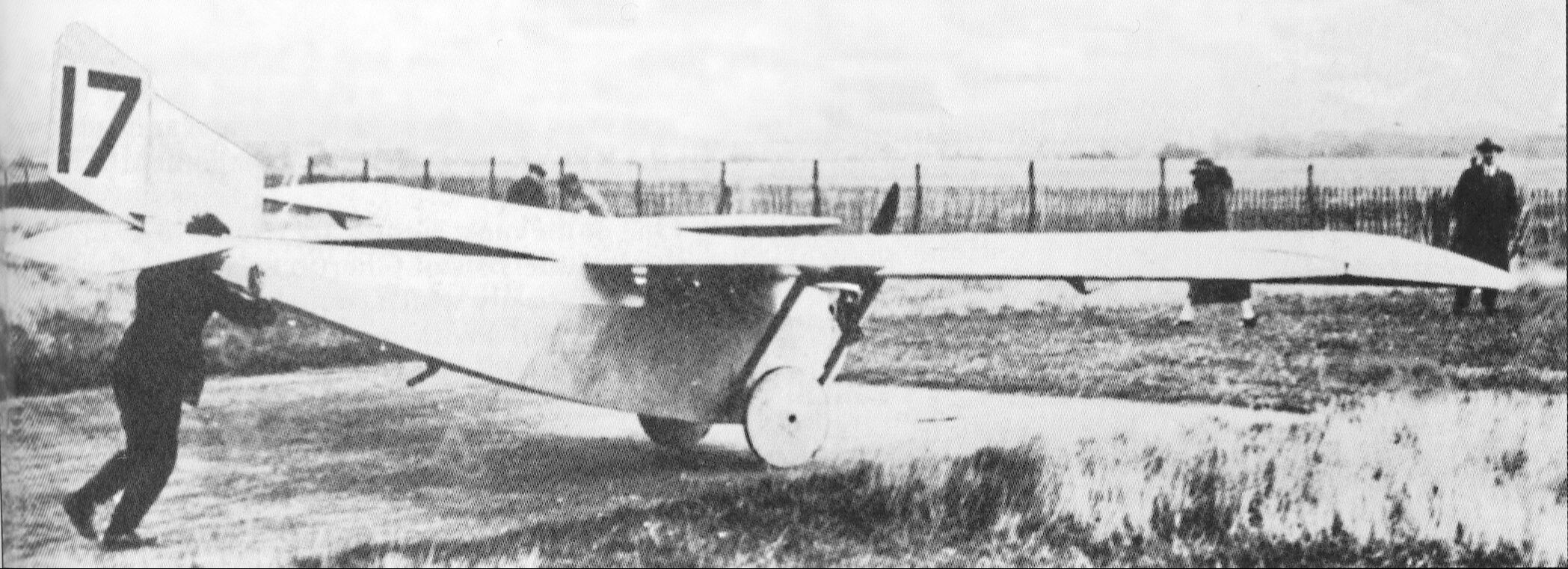

The ANEC.1(Air Navigation and Engineering Co.) was designed by the Australian Bill Shackleton. Powered by a 696 cc Blackburne Tomtit motor cycle engine it did remarkably well, sharing the Daily Mail’s £1000 prize for its 87.5 miles on one gallon of petrol. It also won the Wakefield Prize by climbing to 14.400 ft.

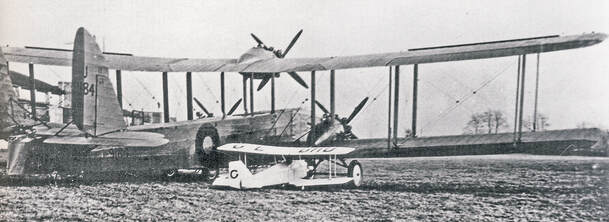

The Gloster Gannet, whose design and construction were greatly admired by judges and observers came from the drawing board of Henry Folland. The 750 cc twin cylinder engine was specially designed for it by John Carden but there was insufficient time to get it properly tested and the Gannet didn’t even get off the ground.

Its tiny size – 18 ft wingspan – is emphasised by the photograph taken some years later alongside the three engined DH 72, de Havilland’s intended replacement for the Vickers Virginia.

Avro were there in some strength. The Model 560 was designed by A. V. Roe himself and it was expected to do well.

It was flown by Bert Hinckler and in the event achieved only third place in the fuel consumption tests – 74 laps at 63 mpg.

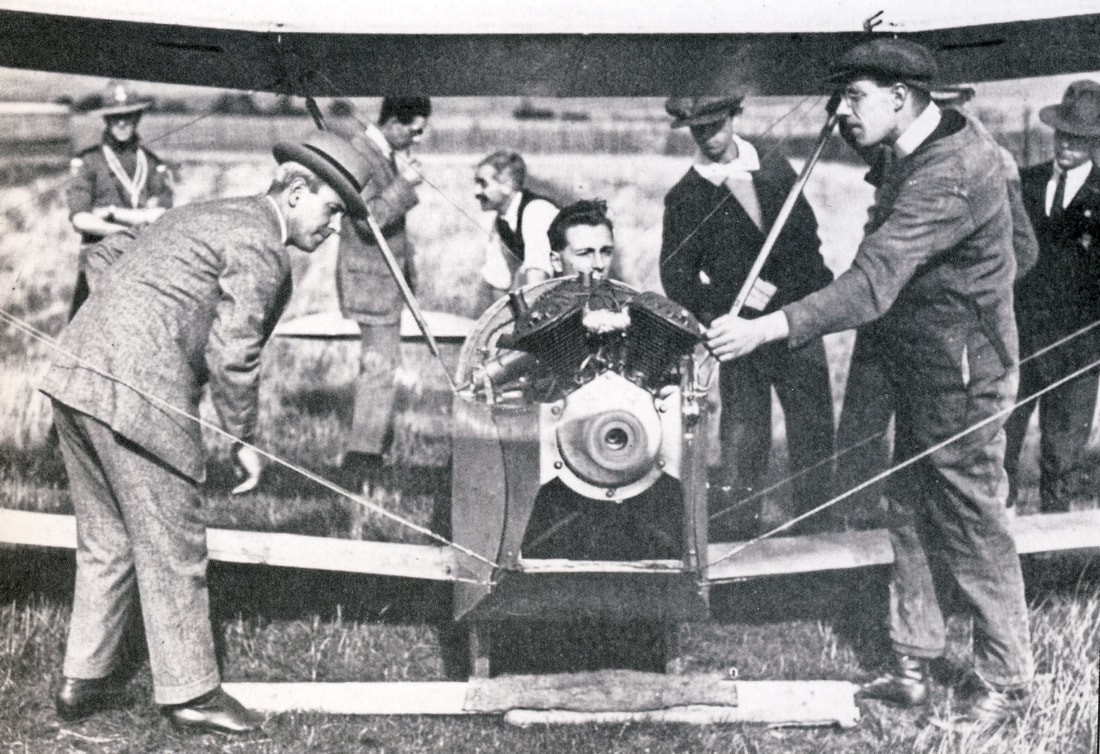

Avro also entered two 30 ft span Model 558 biplanes, designed by Roy Chadwick. Powered by 500 cc twin cylinder B & H engines. One 558 reached 13,850 ft to earn £100 (second place) in the Wakefield height trial.

The other 558 suffered continually from engine problems. Here is a smartly dressed Alliot Roe himself listening to the engine being tested. The ‘wheel chocks’ are a couple of old fence posts.

An unusual entry was the Gull, designed by Oscar Gnosspelius. Its 697cc Burney and Blackburne engine drove two pusher propellers via chains and shafts, an arrangement which probably caused excess drag. And although its wing flexed alarmingly in flight it didn’t break or crash. Nor did it win any prize.

The Vickers Viget biplane proved to be too large and too heavy for its 500cc Douglas twin though it had a sensibly large propeller and a 2.5:1 reduction gear. A broken rocker gear ended its flying.

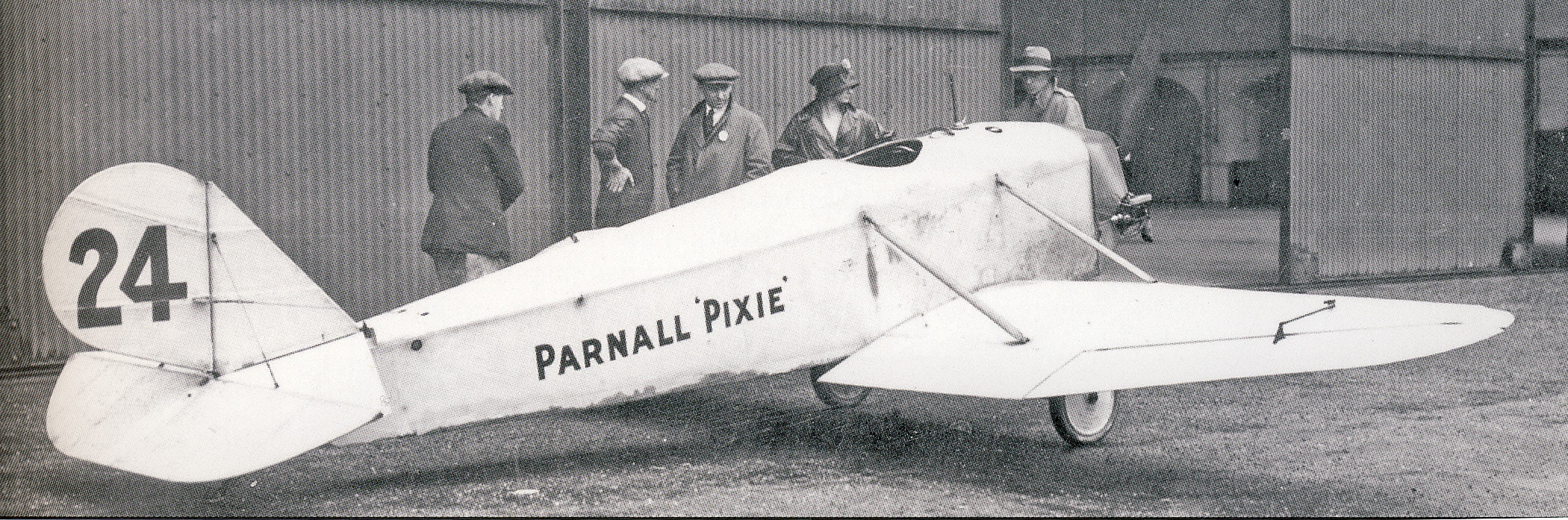

Parnall brought the Pixie with two sets of wings, 28’ 6” and 17’ 10”. Fitted with the larger 736 cc Douglas the short-winged version won the £500 Abdullah prize at 76.1 mph. Its pilot was Norman Macmillan, former RFC ace and test pilot who went on to become the Mail’s Air Correspondent and author of many books.

Parnall brought the Pixie with two sets of wings, 28’ 6” and 17’ 10”. Fitted with the larger 736 cc Douglas the short-winged version won the £500 Abdullah prize at 76.1 mph. Its pilot was Norman Macmillan, former RFC ace and test pilot who went on to become the Mail’s Air Correspondent and author of many books.

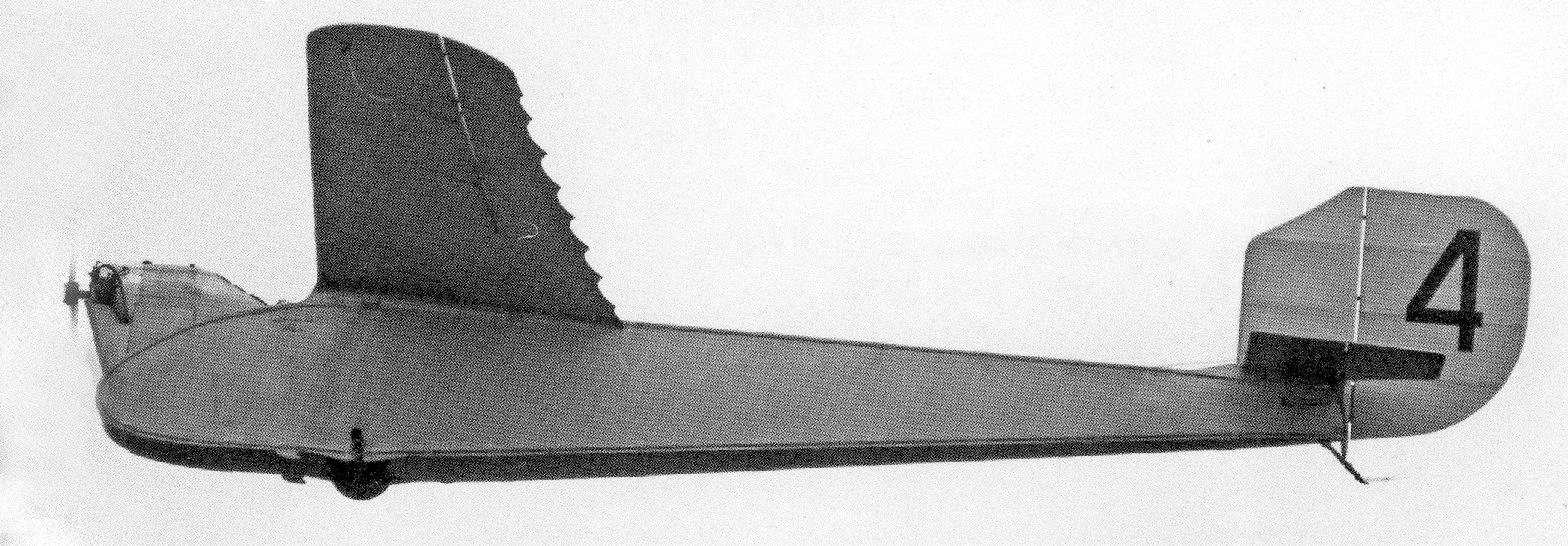

The English Electric Wren is probably the best known of the 1923 competitors because it survives today and flies regularly with the Shuttleworth Collection. Of all the entrants it came closest to looking like a motor-glider with its 37 ft wingspan. The tiny engine was a specially modified 388cc ABC flat twin. Nominally, this could have produced 7 to 8 hp but it drove a large mahogany prop which limited the revs and reduced the effective power output to not much more than 3 hp. Its maximum speed was just over 50 mph so that little engine had to keep going for an hour and three quarters around 14 laps of the triangular course. Its 87.5 mpg equalled the ANEC’s performance and they shared the Daily Mail’s £1000 prize.

For the pilot, too, this was something of an endurance test. He sat directly behind the unsilenced open exhausts of the noisy engine and, without a windscreen endured the blast of the exhaust gases and oil drips directly into his face. He was Walter Longton and for some reason (unconnected with but appropriate for this contest) was known as ‘Scruffy’. He had another indignity to put up with. Getting into the cramped cockpit was not easy.

Standing on the seat it wasn’t possible for him to slide his legs forwards because the bar at the front of the cockpit opening was too low. He had to bend his knees and could do that only if he faced backwards - or sideways. With his knees now under the bar he then had to roll over, somehow manoeuvring round the inconveniently place control column. Phew!

Standing on the seat it wasn’t possible for him to slide his legs forwards because the bar at the front of the cockpit opening was too low. He had to bend his knees and could do that only if he faced backwards - or sideways. With his knees now under the bar he then had to roll over, somehow manoeuvring round the inconveniently place control column. Phew!

De Havilland entered two DH 53s. Here is Major Harold Hemming in Sylvia II cheerfully chatting to an official before starting the Douglas flat-twin. The other DH53, which was flown by Geoffrey de Havilland himself was named Humming Bird, the name by which the type became known.

In the preliminaries, they found that the tailplane was 3 inches too wide to pass through the gate. DH borrowed a saw and promptly cut off the offending excess.

In the preliminaries, they found that the tailplane was 3 inches too wide to pass through the gate. DH borrowed a saw and promptly cut off the offending excess.

Expectations were high and they were seen as potential winners. But . . . they both had trouble with their engines. A collector pipe and silencer were cut off, various propellers were tried. Nothing would persuade the engines to run properly for long enough to show the aeroplane’s true capabilities. They recorded 59.3 mpg in the economy test but that was not their strong point.

One of the French entries was the Peyret Avionette. Louis Peyret was Bleriot’s chief engineer and designed and built aeroplanes in his own right. He had competed in England before, producing the tandem winged glider in which Alexis Maneyrol won the 1922 Glider Competition at Itford Hill.

One of the French entries was the Peyret Avionette. Louis Peyret was Bleriot’s chief engineer and designed and built aeroplanes in his own right. He had competed in England before, producing the tandem winged glider in which Alexis Maneyrol won the 1922 Glider Competition at Itford Hill.

The Avionette was built for a French competition held in August (1923). Flown there by Maneyrol, the Avionette had won the speed and fuel economy prizes and had also set a class world altitude record of 12,750 ft. And now, here it was at Lympne, ready to take off for the altitude prize on the last day of the competition.

The little yellow Avionette, powered by a 16 hp 750 cc Sergant engine climbed away strongly. Some time later it returned and Maneyrol, clearly pleased with his performance dived down and sped past the grandstand at 100 ft in a celebratory fly-past. It might have been the gusty conditions that over-stressed the aircraft or just excess speed. A strut broke and the wing folded backwards. Alexis Maneyrol died in the crash.

The barograph was recovered and confiscated by the contest organisers although some of Maneyrol’s team claimed that he had won the height prize. However, in what some would say was typically French fashion, it was declared that, because of the crash the flight had not been completed and it was therefore invalid for a prize.

The barograph was recovered and confiscated by the contest organisers although some of Maneyrol’s team claimed that he had won the height prize. However, in what some would say was typically French fashion, it was declared that, because of the crash the flight had not been completed and it was therefore invalid for a prize.

It was the last day of the contest and the organisers had hoped that it would end on a happier note with a positive view of small flying machines. They turned to De Havilland for a demonstration of what was widely regarded as the most practical of all the entries, the Humming Bird.

So It was in a rare moment of happily singing engine that Hubert Broad, DH’s test pilot, put on an impromptu aerobatic display, zooming and steep turning in front of the crowd. Some reports said ‘looping and rolling’. That is unlikely but it’s a measure of the favourable impression Broad and the Humming Bird made.

The display helped to bring the DH 53 to wider notice. After the competition the engine was replaced by a Blackburne Tomtit. There was enough interest for orders to be forthcoming from Australia, Czechoslovakia, Russia and, from the RAF, an order for eight Humming Birds.

A couple of months after the Lympne Trials, an Aero and Automobile Show was planned in Brussels. It was decided to show the Humming Bird and Alan Cobham proposed to fly it there. The small fuel tank meant its range was too short so he had an extra tank fitted on the fuselage behind the cockpit.

The display helped to bring the DH 53 to wider notice. After the competition the engine was replaced by a Blackburne Tomtit. There was enough interest for orders to be forthcoming from Australia, Czechoslovakia, Russia and, from the RAF, an order for eight Humming Birds.

A couple of months after the Lympne Trials, an Aero and Automobile Show was planned in Brussels. It was decided to show the Humming Bird and Alan Cobham proposed to fly it there. The small fuel tank meant its range was too short so he had an extra tank fitted on the fuselage behind the cockpit.

There was a snag. The fuel wouldn’t flow easily from the auxiliary to the main tank, it needed a pump. 'Easy', said Cobham, 'put a rubber tube in the filler cap'. With the other end in his mouth, Cobham blew and pressurised the rear tank. After the show, he set off to fly home. It was winter and it was cold. He punched into a headwind and made very slow progress. So slow that he was overtaken by a goods train. He admitted defeat, landed and took a train to the ferry.

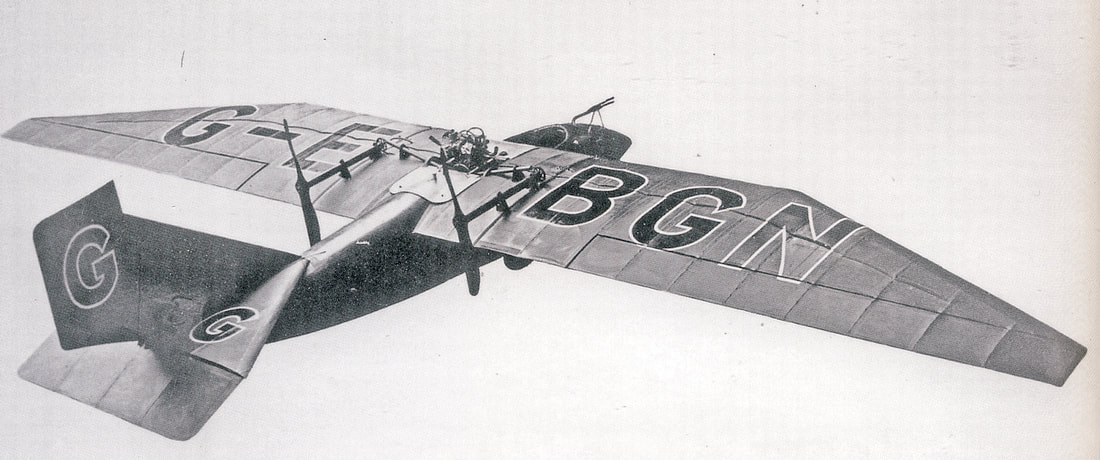

In RAF Service, the DH 53 made its name in an unusual way, probably the highlight of its career. Two Humming Birds were fitted with this complicated harness and hung beneath the R33 airship. The release was easy. Re-attaching took a couple of attempts to get the approach right until, on 4th December 1925 there was success. The Humming Bird was released, flew around independently then it climbed back underneath the R33 and successfully latched itself on to the hook. Actually, it was the pilot who did all the work. He rejoiced in having a splendid name – Sqn Ldr Rollo Amyat de Haga Haig.

In RAF Service, the DH 53 made its name in an unusual way, probably the highlight of its career. Two Humming Birds were fitted with this complicated harness and hung beneath the R33 airship. The release was easy. Re-attaching took a couple of attempts to get the approach right until, on 4th December 1925 there was success. The Humming Bird was released, flew around independently then it climbed back underneath the R33 and successfully latched itself on to the hook. Actually, it was the pilot who did all the work. He rejoiced in having a splendid name – Sqn Ldr Rollo Amyat de Haga Haig.

The RAF sold its Humming Birds to civilian owners in 1927 and over the years all have disappeared. All but two, that is. The De Havilland museum has the fuselage of J7326 and G-EBHX, the prototype, the very one which flew in the 1923 contest and was blown to Brussels by Cobham is part of the Shuttleworth Collection. Its record at Old Warden is rather intimidating. Flown only by experienced and expert pilots it has put two in hospital - forced landings after engine failure, of course - and finally there was the tragic accident in 2012 which is still in our memories. There is talk of its being repaired. What will actually happen after that is uncertain.