The Brunswick LF-1 Zaunkönig (Jan 2013)

In 1945, as the Allied armies swarmed over Germany, there was another invading force – groups of specialist units intent on capturing German secrets and technology. Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown led a British aviation team and managed to fly most of the Luftwaffe’s aeroplanes, from the Messerschmitt 163 rocket fighter to the Blohm und Voss 222 6- engined flying boat. One less exotic type he encountered was the Zaunkönig (Wren) which looked rather like a mini-Storch. An example was brought back to England for thorough testing.

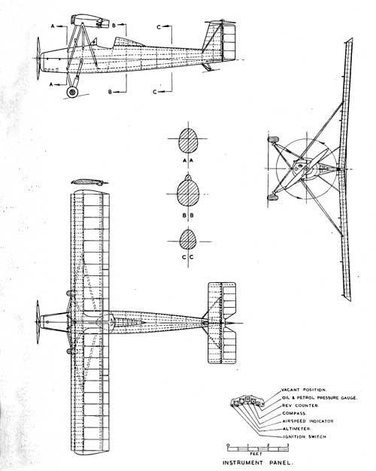

The Braunschweig LF-1 had been designed and built in 1939 by Prof. Ing. Hermann Winter and his students at the University of Brunswick. Its span was just 26’5” and its a.u.w. 776 lb. The intention was to produce a light aeroplane so safe and ‘fool-proof’ – unstallable and unspinnable - that pupils could fly solo without any dual instruction. Winter maintained that training could be as little as one hour’s ground briefing, reduced to a mere five minutes for anyone with gliding experience.

The Braunschweig LF-1 had been designed and built in 1939 by Prof. Ing. Hermann Winter and his students at the University of Brunswick. Its span was just 26’5” and its a.u.w. 776 lb. The intention was to produce a light aeroplane so safe and ‘fool-proof’ – unstallable and unspinnable - that pupils could fly solo without any dual instruction. Winter maintained that training could be as little as one hour’s ground briefing, reduced to a mere five minutes for anyone with gliding experience.

|

The desire to achieve solo flight without tuition in costly dual-control aircraft might have arisen from the glider training methods in use in pre-war Germany. Pupils were routinely taught in solo gliders right from the start, first sitting in the glider on the ground facing into wind and using ailerons to keep the wings level. Then they would be pulled along by a winch to practise steering with the rudder. A series of slightly faster tows across the field lifted the glider off the ground, briefly, for a low hop to discover the effect of the elevator. The hops became higher until pupils were achieving takes-offs and landings, at first with the winch cable providing some safeguard against stalls. Next higher hops allowed tentative turns. This took a long, long time and, with dragging gliders back to the starting point after every hop, was more fitness and character building than flying training, but it worked for thousands in the Hitler Youth. The Zaunkönig would circumvent this whole time consuming process by immediately getting the pupil off the ground into the upper air where he could really discover the flying experience in safety.

|

Winter had previously designed aeroplanes and gliders in Bulgaria and also worked for a time at Fieseler, who built the Storch. The Zaunkönig, similarly, was generously provided with a panoply of slottery and flappery. There was a full-span fixed slat on the leading edge of the wing, half-span slotted flaps on the trailing edge and slotted ailerons. When the flaps were lowered (max. angle 40°), the ailerons also drooped. The Zündapp engine was made by a motor-cycle manufacturer. An air-cooled 4-cylinder engine with single ignition, it produced 51 hp and ‘ran very sweetly’ producing a max. airspeed of 87 m.p.h.

The prototype was constructed and flown in December 1940. Its first flight was made by Winter himself. In 1942 part of the wing broke in testing and the Zaunkönig crashed. A second prototype was built in 1943 and this was the aeroplane brought to the UK in 1945. Thorough testing by Eric Brown and the pilots of the RAE confirmed the German performance figures – typical take-off run, 55 yds, landing run as little as 29 yds, cruise speed, 53 mph, slowest flying speed, 29 m.p.h. – as far as could be measured with the instruments available.

The prototype was constructed and flown in December 1940. Its first flight was made by Winter himself. In 1942 part of the wing broke in testing and the Zaunkönig crashed. A second prototype was built in 1943 and this was the aeroplane brought to the UK in 1945. Thorough testing by Eric Brown and the pilots of the RAE confirmed the German performance figures – typical take-off run, 55 yds, landing run as little as 29 yds, cruise speed, 53 mph, slowest flying speed, 29 m.p.h. – as far as could be measured with the instruments available.

Most of the pilots found flying the Zaunkönig ‘an interesting experience’. Getting into the small cockpit close under the wing was quite a gymnastic manoeuvre. The engine started easily and with no ignition check or elevator trimmer it was soon time for take-off. The briefing was that flap position was ‘anywhere you like’ and on opening the throttle the aircraft ‘cannot fail to fly itself away’. It left the ground at 44 m.p.h. flaps up or 31 m.p.h. flaps down. The lack of trimmer was not a problem as all three controls were light and pleasantly balanced. Approach to land was at 45 m.p.h. flaps up or 40 m.p.h. flaps down. There was no need to flatten out. The aircraft approached in a three point attitude and the pilot could be told to ‘wait until the ground hits the aircraft’. The undercarriage was strengthened to allow it to absorb the shock of the widest range of landing techniques - or should that be lack of technique.

‘Stalling’ tests were carried out with wool tufts attached to the upper surface of the wing. These were filmed from a following helicopter and showed that, at about 30 m.p.h., engine off or engine on, the centre section of the wing stalled but the outer section went on flying and the ailerons continued to give full lateral control. The Zaunkönig effectively ‘turned into a parachute’. The trials went on to their logical final challenge. Handel Davies, head of the RAE Aerodynamics Section, had previously had a little instruction in a dual-control Magister. He was given half an hour’s briefing, put in the Zaunkönig and successfully flew a solo circuit.

After being wrung out at Farnborough, there seemed to be no useful military function for the Zaunkönig and it was tested by the Civil Aviation Flying Unit of the Ministry of Civil Aviation at Gatwick. There were ideas of using it to promote the expected surge in private flying so it was sold to the Ultra Light Aircraft Association in May 1949.

‘Stalling’ tests were carried out with wool tufts attached to the upper surface of the wing. These were filmed from a following helicopter and showed that, at about 30 m.p.h., engine off or engine on, the centre section of the wing stalled but the outer section went on flying and the ailerons continued to give full lateral control. The Zaunkönig effectively ‘turned into a parachute’. The trials went on to their logical final challenge. Handel Davies, head of the RAE Aerodynamics Section, had previously had a little instruction in a dual-control Magister. He was given half an hour’s briefing, put in the Zaunkönig and successfully flew a solo circuit.

After being wrung out at Farnborough, there seemed to be no useful military function for the Zaunkönig and it was tested by the Civil Aviation Flying Unit of the Ministry of Civil Aviation at Gatwick. There were ideas of using it to promote the expected surge in private flying so it was sold to the Ultra Light Aircraft Association in May 1949.

Initially, in 1976, it went back to its roots and here it is now as D-EBCQ in the museum at Oberschleissheim near Munich.

But there’s a twist in the tale. Back in 1954, encouraged by the positive reports from the RAE in the late 40s, Dr Winter built a third Zaunkönig. It happened to be the first new-build aeroplane to be registered in post-war Germany, D-EBAR. Winter hoped it would have a future as an affordable ‘People’s Aeroplane’. In April 1957 the wartime fighter ace Heinrich Bär was invited to test it. He managed to do this so thoroughly that he got the Zaunkönig into a flat spin. Now if an aeroplane ‘cannot be spun’ there’s a perverse logic that says it can’t be recovered from any spin that it does get into. Bär was fatally injured in the subsequent crash and the aircraft was a write-off - as was any plan to build another.

But there’s a twist in the tale. Back in 1954, encouraged by the positive reports from the RAE in the late 40s, Dr Winter built a third Zaunkönig. It happened to be the first new-build aeroplane to be registered in post-war Germany, D-EBAR. Winter hoped it would have a future as an affordable ‘People’s Aeroplane’. In April 1957 the wartime fighter ace Heinrich Bär was invited to test it. He managed to do this so thoroughly that he got the Zaunkönig into a flat spin. Now if an aeroplane ‘cannot be spun’ there’s a perverse logic that says it can’t be recovered from any spin that it does get into. Bär was fatally injured in the subsequent crash and the aircraft was a write-off - as was any plan to build another.