The Roaring (Early) Twenties (Sept 2015)

Although the Wright brothers’ first powered flight was in 1903, it’s more realistic to date the development of aviation to 1908 when Wilbur’s visit to France shocked the Europeans into action. Just two years later the speed record, set by a Bleriot XI, stood at 106.5 km/hr. Urged on by competition and a series of generous prizes, by September 1913 it was 203.8 km/hr. Then came the war and aviation took a different course.

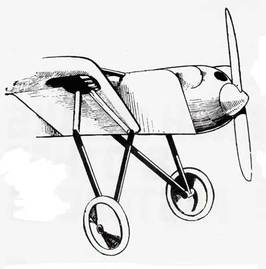

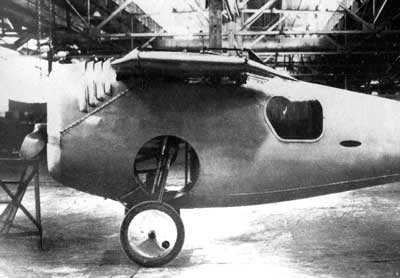

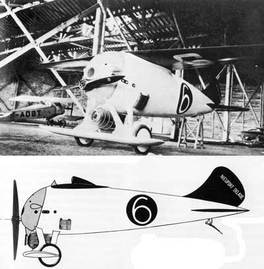

In 1919, the old pre-war prizes re-emerged and war-surplus fighters encouraged early entrants. But many designers knew they could do better. Unhampered by the need to build in ease of maintenance and resistance to battle damage they were free to strive for pure speed. The forward thinking was shown as early as the Paris Air Show in 1919 when this Clement-Moineau design was shown – a monoplane with retractable undercarriage. Despite its promise, this was its only appearance and it faded into obscurity.

In 1919, the old pre-war prizes re-emerged and war-surplus fighters encouraged early entrants. But many designers knew they could do better. Unhampered by the need to build in ease of maintenance and resistance to battle damage they were free to strive for pure speed. The forward thinking was shown as early as the Paris Air Show in 1919 when this Clement-Moineau design was shown – a monoplane with retractable undercarriage. Despite its promise, this was its only appearance and it faded into obscurity.

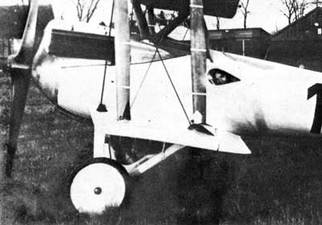

On its very first flight, Freddie Raynham elected to fly over the speed record course at Martlesham Heath and promptly broke the British record with a speed of 161 mph. Before the Derby, he hurt his knee in another incident and asked his friend Frank Courtney to fly in the race.

The Semi-quaver was being displayed at Olympia and Courtney decided not to bother with a test flight after it was re-assembled. His first flight in it was in the race itself. He soon realised that a too-coarse propeller pitch was overloading the engine and raising its temperature. Ignoring this he opened the throttle wide for the last lap. Scalding water from an overflow pipe was being thrown into the cockpit. Distracted, he pulled too tightly in a pylon turn and briefly blacked out. This was a completely new and frightening experience and he thought there must be something seriously wrong with him. He kept quiet about it for months afterwards in case the medical authorities found out and threatened his licence.

Steaming across the line as race winner he closed the throttle and turned into land. He was unaware that the undercarriage shock absorbers had been tightened so that the racer could sit neatly on its stand at Olympia and no-one had remembered to re-adjust them. At the first bump in the grass the Semi-quaver bounded into the air, clipped a wing-tip and overturned. Thankfully, Courtney was quite unhurt, apart from ‘some light scalding of the head’. This event was Martinsyde’s last throw. The company did not survive the post war slump leaving its young mechanic, one Sydney Camm, to look for another job.

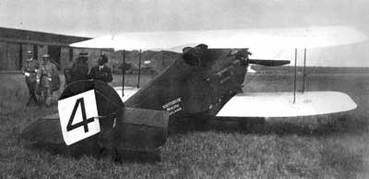

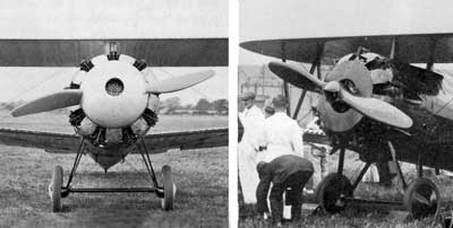

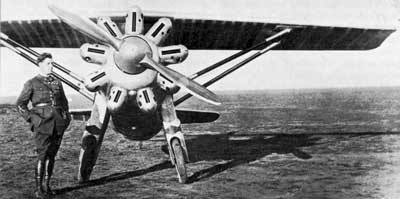

At the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company - Bristol - Roy Fedden had designed a new engine after extensive research and considerable expense. The Jupiter was not ready for flight testing until 1919, much too late for its intended wartime use. Fedden persuaded Frank Barnwell, the designer of the famous Brisfit, to produce a racer for the Jupiter. In accommodating the large 52½ inches diameter engine, it was probably over-built and heavy. Even the tailplane had double spars.

The Semi-quaver was being displayed at Olympia and Courtney decided not to bother with a test flight after it was re-assembled. His first flight in it was in the race itself. He soon realised that a too-coarse propeller pitch was overloading the engine and raising its temperature. Ignoring this he opened the throttle wide for the last lap. Scalding water from an overflow pipe was being thrown into the cockpit. Distracted, he pulled too tightly in a pylon turn and briefly blacked out. This was a completely new and frightening experience and he thought there must be something seriously wrong with him. He kept quiet about it for months afterwards in case the medical authorities found out and threatened his licence.

Steaming across the line as race winner he closed the throttle and turned into land. He was unaware that the undercarriage shock absorbers had been tightened so that the racer could sit neatly on its stand at Olympia and no-one had remembered to re-adjust them. At the first bump in the grass the Semi-quaver bounded into the air, clipped a wing-tip and overturned. Thankfully, Courtney was quite unhurt, apart from ‘some light scalding of the head’. This event was Martinsyde’s last throw. The company did not survive the post war slump leaving its young mechanic, one Sydney Camm, to look for another job.

At the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company - Bristol - Roy Fedden had designed a new engine after extensive research and considerable expense. The Jupiter was not ready for flight testing until 1919, much too late for its intended wartime use. Fedden persuaded Frank Barnwell, the designer of the famous Brisfit, to produce a racer for the Jupiter. In accommodating the large 52½ inches diameter engine, it was probably over-built and heavy. Even the tailplane had double spars.

But the performance of the Bristol Bullet was compromised more by the streamlining of the cylinders. Many spinners were tested, usually failing from unbalanced vibration or cracking. All were little better than the desperation flat plywood plate. Nothing seemed to work as it should and the end result was a disappointing second place in the 1921 Derby.

The Bullet was not the only string to Bristol’s bow. Although the RFC/RAF had treated it with scant regard and banished it to the Middle East, the Bristol M.1C made its mark in history. It was bought by the Chilean Air Force and in 1919 Captain Godoy flew one from Santiago to Argentina – and back. It was the first aeroplane to fly across the Andes. Back in Bristol an M.1C was cleaned up, painted red and fitted with a 100 hp Cosmos Lucifer radial engine. It went on to be the handicap winner of the 1922 Aerial Derby.

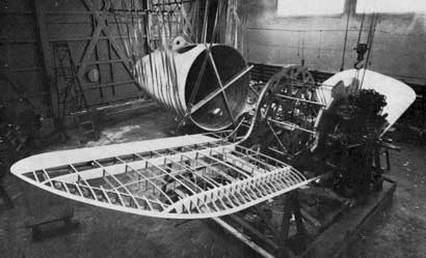

The aeroplane really meant to win the Derby was the Bristol Type 72. Built with a bulky but light thin-walled monocoque fuselage the spindly undercarriage retracted neatly into the bulbous wing roots.

The 490 hp Jupiter had a specially shaped spinner incorporating a duct to admit cooling air. An ill-timed strike at the works caused such disruption to last minute work on this spinner that the 72 had to be withdrawn from the race. But there was still time to enter the Coupe Deutsch. Shipped hurriedly to France, its test flights were seriously disappointing. Something as salvaged from the journey. The engine was removed and sold. Brought back to Bristol, the Type 72’s end was ignominious. The advanced fuselage was cut in two and made fine children’s play sheds.

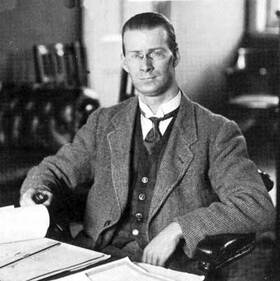

H P Folland made his name as designer of the successful SE 5a. By 1917 he was Chief Designer of the British Nieuport company (which later emerged as the Gloster Aircraft Company). Asked to design a racer, he adopted a novel approach. A firm proponent of the biplane he used a thick high-lift section for the upper wing with a medium lift convex section for the lower. The aim was to make the drag of the lower wing ‘almost disappear in cruising flight’.

He squeezed in a 530 hp Napier Lion with both water and fuel tanks in the hump below the upper wing. It was described as a cross between a bear and a camel and the name Bamel stuck. Finished just in time for the 1921 Aerial Derby (final repairs and adjustments delayed take-off to just 10 minutes before the deadline) the Bamel roared round the circuit and took both speed and handicap prizes.

The following year at the 1922 Derby, cleaned up and fitted with even smaller wings, it won the speed prize. The team then quickly packed for France with high hopes of winning the prestigious Coupe Deutsch. Its pilot was the flamboyant but careless Welshman, Jimmy James. After an impressive take-off there was a bizarre incident on the first lap. James had prepared his map by sticking it to a piece of plywood and hanging it round his neck on a piece of string. Suddenly, this blew out of the cockpit and James found himself being garrotted by the sawing string. Somehow, he managed to find his penknife and cut the string but by then he was lost and his race was over. Ironically, all but one of the other competitors had been eliminated. The next day, James flew a very fast, but pointless lap and the team left for home in humiliation.

The Bamel was renamed Gloster I and largely rebuilt with even smaller wings for the 1923 Derby. Fitted with a specially tuned Lion engine it frightened off most of the opposition and recorded its third consecutive Derby win. Sadly, that was the last Aerial Derby. The future principal race was the King’s Cup in which competitors were handicapped so the quest for pure speed largely disappeared from the British racing calendar

In the search for speed in post-war France two rivals, both producers of military fighters, quickly showed their hands. Spad’s S.20 fighter first flew in May 1918 and was the basis of their challenge. Its wings were clipped and their area halved. There was a belief that eliminating the gap between the fuselage and upper wing would greatly reduce drag. This was achieved partly by deepening the fuselage to accommodate the 320 hp Hispano-Suiza engine.

Its rival was the Nieuport-Delage 29V, more conventional in appearance but carefully streamlined and highly polished. They were entrants in the race for the Gordon Bennett trophy, an annual air race since 1909. The Spad was fast but ‘flew like a worm’. Its tiny fin and rudder guaranteed directional instability but it was the overheating engine which cut short its race. Hastily repaired, it set off on its second attempt half an hour before the race closed. With just 30 miles to go, the oil pressure gauge burst, spraying the pilot with scalding oil. Squirming to one side he realised that the airfield was just ahead. Half blinded, he thrust the aeroplane onto the ground in a high-speed barely controlled downwind landing which seemed to go on for ever. Despite the rough treatment the tough Spad was completely undamaged. The honours went to the Nieuport.

Two weeks later the pair were again competing in a bid to take the world speed record. First the Spad raised the record, then the Nieuport pushed it to 296.7 km/hr and, a few days later became the first to break the 300 barrier with a speed of 302.5 km/hr. The Spad replied with 309 km/hr and that seemed to be unbeatable. The Nieuport engineers took the 29V into a closed hangar. They removed the windscreen and covered the drag-producing cockpit with a sliding hatch.

After take off, the pilot closed the hatch and flew the course, reportedly at an altitude of no more than 4 metres, peering through two small fish-eye side windows. The record, 313 km/hr, was back with Nieuport.

The record holder had another advantage over the Spad. Cooling the large hard-worked racing engines required ever-larger radiators which caused serious drag. Water was the only liquid coolant available (glycol was not introduced until the late 20s). In 1918, a M. Lamblin had designed a novel type of radiator using radially mounted copper fins. Tests showed that this had twice the efficiency of the usual honeycomb radiator and, of course much less drag. When these ‘lobster pots’ became available they were seized upon by the racing fraternity across the world and more than 30,000 were built. Mounted by four bolts they could be changed in 10 minutes. When fitted to the Nieuport 29V, it was 25 km/hr faster.

The successful 29V was ripe for development. The wing was strengthened and built with a more accurate profile. The second wing had a lesser role and shrunk to become little more than an extended axle. Thus the sesquiplane emerged (sesqui – more than one, but fewer than two). In 1922 it raised the speed record to 330.3 km/hr and comfortably won the Coupe Deutsch. Maybe that should be uncomfortably – sitting so close to the engine the pilot had blistered feet.

The Hispano engine seemed to have reached the end of its development. Designers were looking for 400 hp at 2000 rpm - higher revs caused excessive prop tip speeds. In America, Wright had built the Hispano under licence and their radical redesign looked to be the answer. A Wright H-3 shipped to France produced 407 hp. It was fitted to the Nieuport Delage 37, another sesquiplane.

The pilot was seated so far forward that his rudder pedals were between the V-8’s cylinder blocks. And somewhere down there was the carburettor. This regularly caught fire, so often that the Type 37 never left the ground and was quietly forgotten.

It was not the only racer which failed to make its mark. René Arnoux had been experimenting with tailless biplanes for many years and was encouraged by the Simplex company to build a monoplane. The result was structurally excellent and a high speed was predicted. The cockpit position above the broad wing did nothing for the pilot’s view which was further restricted by the large Lamblin lobster pot. To prevent over-controlling this sensitive machine restrictive stops were fitted. The pilot insisted that these should be removed. On take off the result was inevitable. The pilot lost control, a wheel broke off and the aeroplane crashed. (René Arnoux was treated rather unfairly. His work was continued by Charles Fauvel and you can still see his legacy at Shuttleworth’s displays where the Fauvel AV-36 glider demonstrates its tight-looping aerobatic capability).

Gourdou-Leseurre had built Breguet 14 parasol fighters during the war and they took this as the basis for their CT racer. It was unusual in several respects with a structure largely of dural tube with steel fittings. The retractable undercarriage clearly relied heavily on the pilot making drift-free landings. The engine, with dural hoods to streamline the exposed cylinders, was the Bristol Jupiter originally fitted to the unsuccessful Bristol 72. It was taken to Marseilles for a race but turned out to be the only entrant. Sportingly, it was withdrawn then showed its potential by flying the 50 km course at 358 km/hr. Afterwards the engine was needed for other things and the CT was never seen again.

Across the Atlantic post-war racing was stimulated by a prize offered at a Pan-American Aviation Convention, held in 1919 in Atlantic City. The Pulitzer brothers promised $5,000 for the greatest distance flown to or from Atlantic City. Other newspapers added to this. Oddly, there was no response until three days before the convention closed. Two Canadians, both ex-RAF, turned up with their war surplus Sopwith Camels planning a barnstorming trip.

Capt. Mansell James rose to the occasion and took off, landing four hours later in Boston, 340 miles away. He had won the Pulitzer, Globe and Herald prizes, altogether worth $10,000. He set off back to Atlantic City to claim the money. At a refuelling stop in Massachusetts he spent the night. The next morning, he asked about the correct railway he should follow, took off - and disappeared. Extensive searches found nothing. It wasn’t until six years later, in 1925 that a temporarily lost hunter emerged from the woods saying that he had seen some aeroplane wreckage in a thicket. More searches again found nothing and the fate of the first ‘winner’ of the Pulitzer prize remains a mystery.

The 1920 Pulitzer race was crowded with entries, mostly war surplus DH 4s. Sadly, one of the turning points was incorrectly placed and the course flown was invalid. In 1921, the tight military budget prevented any service entries and only four civilian pilots finished the five laps. The winner was Curtis’s test pilot, Bert Acosta, flying the Curtis CR which had been built in just nine weeks. His flight looked impressive, but he was having problems. During a turn in the first lap two of the flying wires snapped and the wings began to ‘wobble and buzz’. Undeterred, he kept the throttle wide open and set an unofficial closed-course world speed record of 176.75 mph.

The following year, the military realised that air racing would be good PR and useful for developing high performance aeroplanes and they effectively took over the Pulitzer races. Strangely, this caused the public to lose interest in the races and the crowds diminished. In 1925 the last Pulitzer race was flown.

This review of some of the racers of the 20s will conclude with a look at a remarkable development. In 1920 an invitation was sent to the USA inviting entries to the 1920 Gordon Bennett race in France. The Dayton-Wright company responded. They used the experimental work of Charles Hampson Grant who had been investigating the effect of moveable wing leading and trailing edges. Moreover, they incorporated a retractable undercarriage. Both actions worked simultaneously when the pilot turned a crank. Buried in the monocoque fuselage he had a forward view only by bulging out the flexible celluloid windows with his head. Power, 250 hp, was provided by an engine which was ‘half a Liberty’.

A pre-race demonstration flight showed that the racer had poor directional and marginal longitudinal stability. Flown carefully, with the engine throttled back, a lap of the 100 km course was completed at 165 mph. Tiny extra fins were added to the tailplane. On race day, the racer took off and headed south as the gear was cranked up. Only 20 minutes later, it returned and landed sedately. A cable had failed and prevented the leading edge from retracting.

It might have made no mark in the competition but it was an astonishing demonstration of advanced design features

It might have made no mark in the competition but it was an astonishing demonstration of advanced design features