The Canard – Its Rise and Fall and Rise (Dec 2016)

In the beginning were the Wright brothers and they found their model biplane wing exceedingly unstable. So they fashioned a stabilising surface and tested it, attaching it in front of and then behind the wing. And lo, both positions worked equally well. However, they chose to fix it in front, partly because the ‘horizontal rudder’ would make the inevitable crashes of their full size flyer less painful. And so – the canard was born. (canard: French for ‘duck’, also a ‘groundless rumour’).

It seemed the natural place for to be. They Wrights found that, when their wing lost lift, the machine would dive to the ground. The horizontal rudder would help the machine to ‘parachute down’. Then they hinged the rudder to use it as a pitch control, though it was hinged too near the centre and thus was extremely sensitive.

It makes their ultimate achievement in 1903 all the more admirable in that they taught themselves to fly such an unstable machine in hops lasting just a few seconds.

It seemed the natural place for to be. They Wrights found that, when their wing lost lift, the machine would dive to the ground. The horizontal rudder would help the machine to ‘parachute down’. Then they hinged the rudder to use it as a pitch control, though it was hinged too near the centre and thus was extremely sensitive.

It makes their ultimate achievement in 1903 all the more admirable in that they taught themselves to fly such an unstable machine in hops lasting just a few seconds.

Other pioneers followed the Wrights’ configuration, though with better balanced foreplanes. The chief advantage of a foreplane is that it is set at a greater angle of incidence than the wing. This contributes to the production of lift whereas tailplanes produce a down force. If the angle of attack of the wing were to increase to approach the stalling angle, the foreplane would stall first, automatically dropping the nose and preventing the mainplane from stalling. And in an era when many pilots were self-taught, the canard usefully provided a clear indication of pitch angle. As knowledge was gained and perfomances improved aeroplanes with tailplanes were found to perform better and the canard fell out of use.

Not entirely, although most canards which emerged were one-off experimental aircraft. George Miles built the Libellula in 1942. He had far-reaching plans to develop it into a bomber, eventually to be fitted with six or even eight jet engines. He also envisioned a tri-jet high speed mailplane for BOAC.

Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown tested the Libellula. ‘It wouldn’t stall but settled in a steady descent at 81 mph with the stick held fully back’. There was no enthusiasm for this curious concept and it gently faded away.

In the USA in 1943, Curtiss built three prototypes of a fighter, the XP-55 Ascender. (The name seems to have emerged as the more acceptably spelled version of its nick-name the Ass-ender). The canard, hinged at its leading edge, was free-floating with a balance tab to adjust its angle. The first prototype proved to have vicious stalling characteristics, not just because it was a canard. During a spin test, it flicked inverted and stabilised upside down. The engine had stopped, so the pilot had no need to use the facility to jettison the propeller (as in the Dornier 335) before baling out.

Undeterred, the USAF continued to test the other two prototypes (no spinning below 20,000ft, please) until the programme was cancelled in 1944. One Ascender did reappear at an end-of-the-war airshow. During a roll before a crowd of 100,000, it dived into the ground. The pilot and a passing motorist died. And, despite this less than illustrious record, the third prototype is exhibited still in a museum.

Undeterred, the USAF continued to test the other two prototypes (no spinning below 20,000ft, please) until the programme was cancelled in 1944. One Ascender did reappear at an end-of-the-war airshow. During a roll before a crowd of 100,000, it dived into the ground. The pilot and a passing motorist died. And, despite this less than illustrious record, the third prototype is exhibited still in a museum.

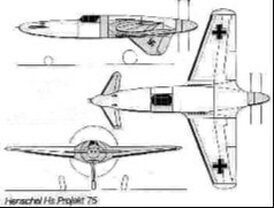

In wartime Germany, where there was no shortage of far out experimental projects - wings swept back, swept forward, swinging wings . . . , Henschel produced a design for a canard fighter. It got no further than drawing board.

Post-war, the French aviation industry produced a far-reaching design of a fighter powered by a dual turbo-jet and ramjet. In 1959 the Nord 1500 Griffon I was tested with a turbo jet only. Then the Griffon II showed that the ramjet worked at high speed, well enough for André Turcat (later the Concorde test pilot) to set a closed circuit world speed record of 1,448 mph. The fact that its fixed delta foreplane made it a successful canard was lost in the problems caused by high temperature stressing of parts of the airframe. The Griffon retired to a museum.

Post-war, the French aviation industry produced a far-reaching design of a fighter powered by a dual turbo-jet and ramjet. In 1959 the Nord 1500 Griffon I was tested with a turbo jet only. Then the Griffon II showed that the ramjet worked at high speed, well enough for André Turcat (later the Concorde test pilot) to set a closed circuit world speed record of 1,448 mph. The fact that its fixed delta foreplane made it a successful canard was lost in the problems caused by high temperature stressing of parts of the airframe. The Griffon retired to a museum.

In the UK plans for canard strategic supersonic bombers were drawn in the design offices of Avro, Handley Page and Vickers but Duncan Sandys’ Defence White Paper of 1957 killed them all. In 1959 in the US, the largest and most spectacular canard, the North American XB-70 Valkyrie, made it to prototype form – two of them. Intended to fly at Mach 3+ at 70,000 ft it was neutered by increasingly capable Soviet missiles and an operational policy change by the USAF to low-level bombing.

In an attempt to get some value from the enormous expense of producing these aircraft, c.$2,000 million each, they were employed in a research programme of long duration high speed flights. In 1966, a Starfighter flew alongside a Valkyrie for some publicity pictures. The fighter got caught up in the Valkyrie’s tip vortex and rolled into it, slicing off one of the bomber’s vertical stabilisers and sending it out of control into the Mojave desert. The other XB-70 was retired – into a museum.

Not all canards were doomed to failure. The first to reach production was the Saab Viggen (‘thunderbolt’ or ‘tufted duck’). One of the design requirements was the ability to operate from short (500 metres) runways. The canard layout was chosen so that the vortex it generated would increase the lift produced by the main wing. Although the Swedish fighter was not immune from spinning its canard allowed it to be flown with the wing at high angles of attack – as much as 38° - before a spin developed.

Over 300 Viggens were made and were in service with the Swedish Air Force for over 30 years. They set the trend for subsequent high performance jet aircraft with computers controlling the complexities of the aerodynamics to achieve maximum manoeuvrability

Over 300 Viggens were made and were in service with the Swedish Air Force for over 30 years. They set the trend for subsequent high performance jet aircraft with computers controlling the complexities of the aerodynamics to achieve maximum manoeuvrability

The Viggen inspired another designer who was planning to build a light aeroplane for himself. As an engineer at Edwards AFB, Elbert Leander (Burt) Rutan was involved in testing the MacDonnell Phantom, riding in the back seat whilst it performed 16-turn spins. He compared its performance with the Saab Viggen and chose the canard configuration for his own plane, so similar to the Saab’s that he called it a VariViggen. He tested the design with an ingenious rig on his car which allowed him to make adjustments to the model by radio control during the tests.

Mike Melvill was so taken with the design (it could carry two people and three suitcases) that he moved house to get a bigger garage to build his own VariViggen. When Rutan came to see his work he was impressed by Melvill and by his wife, Sally, who was an accountant. He invited them both to join his growing company.

With a wingspan of just 19ft the VariViggen cruised at 150 mph and had a range of 400 miles. Over 60 plans were sold, though many fewer were built. Any survivors are in museums but Melvill’s is still flown with 4,200 hours on the airframe.

With a wingspan of just 19ft the VariViggen cruised at 150 mph and had a range of 400 miles. Over 60 plans were sold, though many fewer were built. Any survivors are in museums but Melvill’s is still flown with 4,200 hours on the airframe.

hhe design was well worth development. Rutan abandoned the delta and used GRP to build a larger swept back wing fitted with winglets, not then as fashionable as they have since become. The result was the VariEze with foreplanes for both pitch and roll control. He found that the rudders on the winglets (which move outwards only) induced a sideslip which, on a swept wing automatically produced a roll. Later versions of the VariEze used conventional mid-span ailerons on the main wing.

The prototype flew in 1975. Rutan’s brother, Dick, took it to Oshkosk and completed a 1,638 mile flight to gain an under 500kg class record. It was a sensation. Burt introduced some modifications, changing the VW engine for a Continental and offered eagerly awaited plans for sale. By 1980, over 2000 Vari-Ezes were under construction and soon 300 were flying all over the world. A slightly enlarged version, the Long-Eze, was produced. Dick Rutan and Mike Melville took two of these on a round the world flight in 1997. With a cruising speed of 165 mph and a normal range of 850 miles this was well within their capabilities. By 2005, 800 Long-Ezes had been registered in the US alone

The prototype flew in 1975. Rutan’s brother, Dick, took it to Oshkosk and completed a 1,638 mile flight to gain an under 500kg class record. It was a sensation. Burt introduced some modifications, changing the VW engine for a Continental and offered eagerly awaited plans for sale. By 1980, over 2000 Vari-Ezes were under construction and soon 300 were flying all over the world. A slightly enlarged version, the Long-Eze, was produced. Dick Rutan and Mike Melville took two of these on a round the world flight in 1997. With a cruising speed of 165 mph and a normal range of 850 miles this was well within their capabilities. By 2005, 800 Long-Ezes had been registered in the US alone

The prototype, a Long-Eze and a Vari-Eze parked with their nose-wheels retracted (no parking brake needed).

From the Vari-Eze came the Defiant, an attractive 4-seat push-me-pull-you with twin 160 hp engines. Unfortunately there was insufficient funding for full certification and production so the design was modified for home builders. A modest number were sold.

Clearly, the success of Rutan’s designs had made the canard an acceptable, even desirable layout. It had its own peculiar problem, however. When flown in rain, the effect of the raindrops on the canard caused a slight loss of lift needing back pressure on the stick. This was easily trimmed out but Rutan worked out a modification with a new aerofoil section and a slight reduction in the span of the canard. This eliminated the ‘rain trim change’ at the cost of an increase of 2 mph to the stall speed.

Clearly, the success of Rutan’s designs had made the canard an acceptable, even desirable layout. It had its own peculiar problem, however. When flown in rain, the effect of the raindrops on the canard caused a slight loss of lift needing back pressure on the stick. This was easily trimmed out but Rutan worked out a modification with a new aerofoil section and a slight reduction in the span of the canard. This eliminated the ‘rain trim change’ at the cost of an increase of 2 mph to the stall speed.

Gene Sheehan and Tom Jewett had developed a small (18 hp) engine and asked Rutan to design a suitable aeroplane to use it. Rutan came up with the Quickie, another canard with the unique feature of having the undercarriage on the end of the forewings.

The prototype, built largely by Sheehan but tested by all three was shown at Oshkosh in 1978 where it won the Outstanding New Design Award. Sheehan and Jowett started producing kits in 1980.

Distribution of the kits outside the US was handled by Gary Legare, based in Canada, who had already built a Vari-Eze. He thought a two-seat Quickie would sell well. He modified the design to take a 64 hp VW engine and began producing kits himself. In all over 1000 Quickie kits and 2000+ Q-2 kits were sold.

The prototype, built largely by Sheehan but tested by all three was shown at Oshkosh in 1978 where it won the Outstanding New Design Award. Sheehan and Jowett started producing kits in 1980.

Distribution of the kits outside the US was handled by Gary Legare, based in Canada, who had already built a Vari-Eze. He thought a two-seat Quickie would sell well. He modified the design to take a 64 hp VW engine and began producing kits himself. In all over 1000 Quickie kits and 2000+ Q-2 kits were sold.

The Quickie had a remarkable performance. With a wingspan of 16’ 8” and a gross weight of just 480lbs it cruised at 121 mph with a range of 550 miles. The Q-2 had a larger fuselage increasing the gross weight to 1000 lbs and its more powerful engine raised the cruising speed to 140 mph.

Different in appearance, there were other things which made it different. With the CG so far behind the main wheels, ground handling could be tricky. It was best on smooth runways and the toe-in of the wheels had to be absolutely correct, or the Quickie would lurch off to one side. On take-off, it wasn’t possible to raise the tail, when the Quickie was ready – about 55 mph- it levitated.

Once airborne, the quality of the build could be reflected in the performance. One early builder drew up a smart paint scheme with a coloured line painted along the leading edge of the foreplane. The smart shiny new Quickie charged down the runway but wouldn’t take off. He was advised to remove the line of paint because it was preventing the canard developing lift. The aerofoil section of the design was later modified

Different in appearance, there were other things which made it different. With the CG so far behind the main wheels, ground handling could be tricky. It was best on smooth runways and the toe-in of the wheels had to be absolutely correct, or the Quickie would lurch off to one side. On take-off, it wasn’t possible to raise the tail, when the Quickie was ready – about 55 mph- it levitated.

Once airborne, the quality of the build could be reflected in the performance. One early builder drew up a smart paint scheme with a coloured line painted along the leading edge of the foreplane. The smart shiny new Quickie charged down the runway but wouldn’t take off. He was advised to remove the line of paint because it was preventing the canard developing lift. The aerofoil section of the design was later modified

An interesting Quickie variation was made for Danny Mortensen who wanted a fast biplane for racing. Rutan increased the span to 22 ft and beefed it up, fitting a 160 hp Lycoming. Such was its improved performance that Mortensen set a class world speed record at 232 mph. It proved its worth in another way at the 1983 Reno race meeting. Mortensen was caught in the wake turbulence of another biplane. His Quickie flicked almost inverted at 200 mph just 100 ft above the desert. The ensuing knife-edge crash destroyed the aeroplane; Mortensen climbed out of the cockpit and walked away unhurt.

Alongside the Solitaire in his factory, Rutan built a canard specifically designed for slow flight. (The Vari-Eze’s landing speed was 74 mph, too high for some pilots.) The Grizzly had large Fowler flaps which rolled out behind both the wing and the canard, helping to reduce the landing speed to 40 mph. The oddity of its appearance, with varying amounts of sweep forward and solid booms containing fuel tanks, was added to by its unusual undercarriage and bulging side windows enabling the passengers to see the ground directly below. Rutan said the Grizzly was for camping trips in the bush (its seats could fold flat to make a bed) but that might have been another joke.

Alongside the Solitaire in his factory, Rutan built a canard specifically designed for slow flight. (The Vari-Eze’s landing speed was 74 mph, too high for some pilots.) The Grizzly had large Fowler flaps which rolled out behind both the wing and the canard, helping to reduce the landing speed to 40 mph. The oddity of its appearance, with varying amounts of sweep forward and solid booms containing fuel tanks, was added to by its unusual undercarriage and bulging side windows enabling the passengers to see the ground directly below. Rutan said the Grizzly was for camping trips in the bush (its seats could fold flat to make a bed) but that might have been another joke.

Dick Rutan was keen to do a world record. Some years before Burt had played with the idea of using an enlarged sailplane wing as the basis of a feasible long range aeroplane. After more serious calculations the Voyager was designed. With a wingspan of 110 ft it was powered by tandem Continental engines - 130 hp up front and 110 hp (liquid cooled) in the rear. 7,000 lbs of fuel was carried in 17 tanks, mostly in the twin booms. After a warm up closed circuit distance record of 11,857 miles, Voyager was ready. On 14th December 1986, Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager lined up on the runway of Edwards AFB. 72% of the gross weight was fuel and the wingtips dragged on the ground. Acceleration was slow but after three miles Voyager lifted off.

As they climbed away the starboard winglet was flapping loosely on the upper surface of the wing. Flying alongside in a Beech Duchess Burt Rutan advised his brother to sideslip so that the winglet broke off outwards. This worked, leaving the wires of the missing wing tip light flailing in the exposed bits of foam. The other winglet soon departed without sideslip assistance. The chase plane checked that there was no fuel leakage and Burt calculated that the raw ends of the wings would reduce the range by 6%. This was deemed to be acceptable and Voyager flew west towards Hawaii to take advantage of the trade winds and settled into cruise, mostly on the rear engine. On 23rd December (9 days, 3 mins, 44secs) they landed with 140 lbs of fuel left having flown 24,986 miles. The Rutan brothers and Jeana Yeager were awarded the Presidential Citizens Medal.

In 1984, Rutan formed Scaled Composites to exploit the business potential of the rapid devlopment of prototypes of advanced design. The following year, Beech acquired Scaled Composites and Rutan became a Vice President. His first contract was to design a successor for the King Air, a long serving twin turbo-prop 7-passenger air taxi, also used by many military and non-government organisations. Rutan offered a number of design layouts and Beech asked him to develop the Starship, which looked remarkably like an enlarged Vari-Eze. Rutan built a proof of concept prototype (85% scale) with a variable geometry canard. Beech re-engineered the design for production.

Three prototypes were built and in the process Beech had to learn, expensively, much about the use of composite materials. Development costs exceeded $300 million and the first production model didn’t fly until April 1989. It was not a good time in an economic slowdown to sell expensive aeroplanes and the Starship’s startling appearance and all-glass cockpit were too new for many buyers. Resorting to leasing deals and even ‘free’ maintenance offers didn’t save the Starship. The 53rd, and last of the breed came out of the factory in 1995. Many went straight to the scrapyard. Beech sold Scaled Composites back to Rutan in 1988 and concentrated on developing the King Air.

Part of the Starship’s failure was attributed to the competition. In September 1986, Piaggio flew the first prototype of the Avanti, a three-surface design, which they had patented earlier, with both canard and T-tail. The canard is fitted with flaps which operate at the same time as the main flaps. There was a pause in development due to money problems but the production Avanti was well received by buyers. The 100th aircraft was delivered in 2005

The efficient Avanti can compete with jet rivals like the Cessna Citation but it is not universally welcome. The pusher engines allow the wing to operate in clean air but the propellors chop through the wing’s wash. This creates excessive noise for ground observers and some sensitive airports have banned the Avanti. The upgraded Avanti now has Hartzell scimitar propellors which promise a 68% reduction in noise.

There was a time when the only canards in the sky were Rutan designs but this is no longer the case - apart from the computer controlled military machines when a foreplane seems to be de rigeur. Here are a few. . .

There was a time when the only canards in the sky were Rutan designs but this is no longer the case - apart from the computer controlled military machines when a foreplane seems to be de rigeur. Here are a few. . .

Junqua Ibis Falcon XP E-Go

Lockspieser LDA OMAC 300 prototype OMAC 30

AASI Jetcruzer 50 Avtec 400