The Double Crossing of the R34 (July 2021)

At the start of WWI, the airship was seen as a major threat to Britain, capable of flying unchallenged in British skies and intent on scattering death and destruction on innocent civilians. Count Zeppelin had been flying his airships since 1900 and several well developed airships were being operated by both the German army and its Navy. most effectively in long range reconnaissance flights. British attempts to catch up were hampered partly by the view held by many of the senior military that airships were more trouble than they were worth. Even in the department of naval construction, which had been responsible for the development of the early tank and later aircraft carriers there was a lack of understanding of aeronautics which hindered progress.

Designs were largely copies of older German airships, though they benefitted from the interrogation of Hermann Müller who had managed the girder construction shop of Schütter-Lanz. He had escaped from Germany and offered his services to the Allies. As a result of this, in 1916 the Admiralty had ordered two airships, R 31 and R32 with a framework of wooden girders, like Schütter-Lanz ships.

Then there was a burst of inspiration which started with four Zeppelins setting off to bomb London on 24 September 1916. The raid was a complete failure. All the ships lost their way in the bad weather. One took his bombs home. Another claimed to have bombed London but in fact jettisoned his bombs in the North Sea and went home. A third just disappeared.

Designs were largely copies of older German airships, though they benefitted from the interrogation of Hermann Müller who had managed the girder construction shop of Schütter-Lanz. He had escaped from Germany and offered his services to the Allies. As a result of this, in 1916 the Admiralty had ordered two airships, R 31 and R32 with a framework of wooden girders, like Schütter-Lanz ships.

Then there was a burst of inspiration which started with four Zeppelins setting off to bomb London on 24 September 1916. The raid was a complete failure. All the ships lost their way in the bad weather. One took his bombs home. Another claimed to have bombed London but in fact jettisoned his bombs in the North Sea and went home. A third just disappeared.

The fourth, L33, had been cruising about for so long that the captain decided on a precautionary landing to find out where he was. He loomed out of the low cloud over the village of Little Wigborough in Essex. A volley of gunfire set the airship partly ablaze and L33 crashed. The crew were taken prisoner and the British were gifted the very latest design of airship, one which they had called the ’super Zeppelin’. 645 feet long, with six engines and a disposable lift of 27 tons, the design was so advanced that all British ships under construction were cancelled.

Two new ships were ordered, R33 and R34. The work was given to Beardmore, Armstrong Whitworth and Vickers. Building work began late in 1917 and orders for three more had been placed. When the war ended in November 1918 none of the ships had been finished but the climate had completely changed.

Two new ships were ordered, R33 and R34. The work was given to Beardmore, Armstrong Whitworth and Vickers. Building work began late in 1917 and orders for three more had been placed. When the war ended in November 1918 none of the ships had been finished but the climate had completely changed.

Airships were no longer weapons of war but the kernel of a new form of long range passenger transport that would compete with ocean liners. Under the terms of the Versailles Treaty Germany was required to hand its airships to the Allies. France, Italy, the USA and Britain were all circling, in ‘friendly competition’ to establish commercial routes.

In March 1919 the Aero Club of America issued an invitation for a British airship to cross the Atlantic and visit the USA. That promptly stirred up an argument between the Admiralty and the Air Ministry as to which should respond to the invitation. In the end, the Navy conceded that commercial airship operations were more the concern of Air Ministry. Their Airships decided that the R34, which was almost ready to fly, would carry the flag to the US. On the way, as a diplomatic gesture, it would take an American naval officer and on the return journey, a US Army officer.

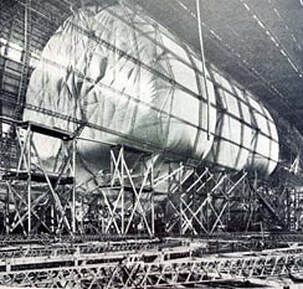

The R34 was built in Beardmore’s Inchinnan Works, near Glasgow. The frames were made of U-shaped duralumin tubes (an alloy of aluminium), braced with wire and covered with linen strips to prevent chafing of the outer covering.

In March 1919 the Aero Club of America issued an invitation for a British airship to cross the Atlantic and visit the USA. That promptly stirred up an argument between the Admiralty and the Air Ministry as to which should respond to the invitation. In the end, the Navy conceded that commercial airship operations were more the concern of Air Ministry. Their Airships decided that the R34, which was almost ready to fly, would carry the flag to the US. On the way, as a diplomatic gesture, it would take an American naval officer and on the return journey, a US Army officer.

The R34 was built in Beardmore’s Inchinnan Works, near Glasgow. The frames were made of U-shaped duralumin tubes (an alloy of aluminium), braced with wire and covered with linen strips to prevent chafing of the outer covering.

The nineteen gasbags were made of rubberised cloth lined with goldbeaters’ skin (the lining of cows’ stomachs), each gasbag being encased in a net of cord mesh.

The main control car was 50 feet long, actually made in two separated sections so that the vibrations of the 275 hp Sunbeam Maori engine weren’t transmitted to the control car and its delicate instruments.

Separate cars held the two wing engines and two engines in the rear car drove a single propeller.

The outer covering of the hull was painted with dope containing aluminium powder to reflect sunlight and prevent superheating (heating of the air inside the hull – more about this later).

The main control car was 50 feet long, actually made in two separated sections so that the vibrations of the 275 hp Sunbeam Maori engine weren’t transmitted to the control car and its delicate instruments.

Separate cars held the two wing engines and two engines in the rear car drove a single propeller.

The outer covering of the hull was painted with dope containing aluminium powder to reflect sunlight and prevent superheating (heating of the air inside the hull – more about this later).

R34 emerged from her shed on 14th March 1919 and her initial five hour maiden flight ended without drama.

Things were different 10 days later in intermittent fog, snow and hail. In these challenging conditions the ship cruised past Newcastle, Liverpool and Dublin. On the way the port elevator somehow jammed into the full down position and the ship limped home. Getting it back into the shed proved troublesome. The propellers and even some of the main girders were damaged.

It wasn’t until 28th May that the repairs and engine changes were completed and R34 was ready to fly again.

Things were different 10 days later in intermittent fog, snow and hail. In these challenging conditions the ship cruised past Newcastle, Liverpool and Dublin. On the way the port elevator somehow jammed into the full down position and the ship limped home. Getting it back into the shed proved troublesome. The propellers and even some of the main girders were damaged.

It wasn’t until 28th May that the repairs and engine changes were completed and R34 was ready to fly again.

It was a short flight to East Fortune, her home base, just east of Edinburgh. But East Fortune became covered in fog so the captain, Major George Herbert Scott, loitered over the North Sea till the fog finally cleared – 21 weary foodless hours later.

Before the transatlantic journey an endurance test was needed, a roundabout flight to the Baltic and back. Before they took off, on 17th June, they learned that, just two days before, the Atlantic had been crossed by a Vickers Vimy flown by Alcock and Brown. Had it not been for that mis-handling at Inchinnan, the R34 could have been first.

As it was, the last minute preparations were made on 1st July and at midnight, the whole crew sat down for a meal. Then they all climbed aboard as a heavy tractor pulled open the doors of the shed. Scott ordered ‘Walk her out’ and his order was repeated by a bugle call.

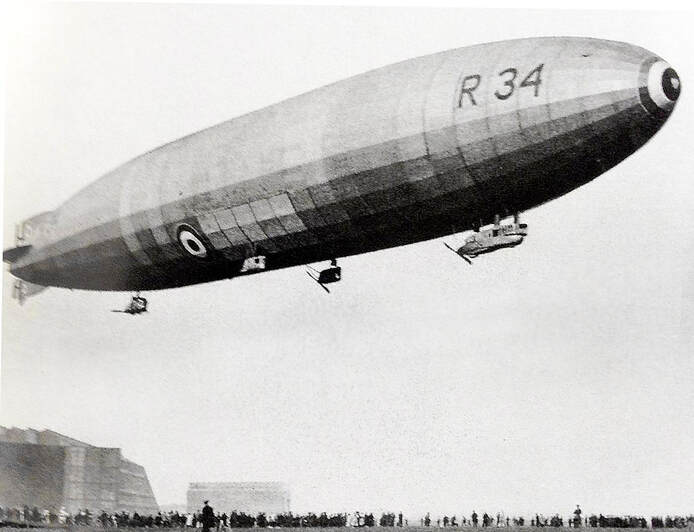

The 550 strong handling crew pulled R34 into position to face the light, cold north east wind. It was misty and the sky was covered by dark low cloud so no photographs were taken to record the departure. At 1.42 am on Tuesday 2nd July the engines were started, the ropes released and the ship rose slowly. Safely clear, the clutches were engaged, the nose lifted and the ship disappeared into the cloud.

Before the transatlantic journey an endurance test was needed, a roundabout flight to the Baltic and back. Before they took off, on 17th June, they learned that, just two days before, the Atlantic had been crossed by a Vickers Vimy flown by Alcock and Brown. Had it not been for that mis-handling at Inchinnan, the R34 could have been first.

As it was, the last minute preparations were made on 1st July and at midnight, the whole crew sat down for a meal. Then they all climbed aboard as a heavy tractor pulled open the doors of the shed. Scott ordered ‘Walk her out’ and his order was repeated by a bugle call.

The 550 strong handling crew pulled R34 into position to face the light, cold north east wind. It was misty and the sky was covered by dark low cloud so no photographs were taken to record the departure. At 1.42 am on Tuesday 2nd July the engines were started, the ropes released and the ship rose slowly. Safely clear, the clutches were engaged, the nose lifted and the ship disappeared into the cloud.

The ship did not have space for such a large crew and several men had to sling their hammocks on any convenient space inside the envelope.

There was no galley. A steel plate welded to the exhaust of the engine behind the control car served as a substitute hob.

Crossing Scotland in darkness the airship headed out over the Atlantic. Although they were carrying almost 6000 gallons of petrol Major Scott had to be economical in its use. He took advantage of a following wind and shut down three of the engines, reducing fuel consumption to 25 gallons per hour whilst cruising at 34 mph.

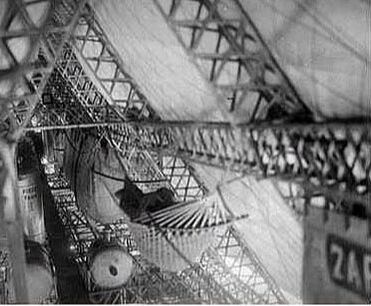

The dark plank of a walkway is visible on the left alongside

a silver fuel tank. A round tank of drinking water is below.

There was no galley. A steel plate welded to the exhaust of the engine behind the control car served as a substitute hob.

Crossing Scotland in darkness the airship headed out over the Atlantic. Although they were carrying almost 6000 gallons of petrol Major Scott had to be economical in its use. He took advantage of a following wind and shut down three of the engines, reducing fuel consumption to 25 gallons per hour whilst cruising at 34 mph.

The dark plank of a walkway is visible on the left alongside

a silver fuel tank. A round tank of drinking water is below.

Then a stowaway was discovered. William Ballantyne was a regular crew member who had been taken off the crew list, possibly because of the extra passengers. His hiding place between two of the gasbags was cold and he became unwell and nauseous from the smell of the hydrogen. Whilst Maitland and Scott sympathised with his motive it was bad for discipline. Had they been over land, he would have been ejected by parachute. Instead he made to work his passage, operating hand pumps, degreasing and cooking.

A second stowaway turned up, Wopsie, the crew’s little cat. It’s not clear whether Wopsie came with Ballantyne or came independently but his presence added whimsy to the voyage.

A second stowaway turned up, Wopsie, the crew’s little cat. It’s not clear whether Wopsie came with Ballantyne or came independently but his presence added whimsy to the voyage.

On the second day they began to have problems with superheating, the term used for heating of the air inside the envelope. Sunlight on the envelope has an exaggerated effect on the air trapped inside. At one point, when the outside temperature was 40° F the inside temperature rose to 106° F. The airship behaved like a hot-air balloon, as the warmed air expanded the airship rose.

To have countered this by releasing hydrogen would have been wasteful so Captain Scott had to use the elevators to force the nose down. This disturbed the airflow along the ship and the increased drag reduced their speed. Nevertheless, it was worth doing to get down to a layer of low cloud where the airship would be out of the sun and the trapped air would cool down.

Everyone was happy with this apart from Major G H Cooke, the navigator. He needed to take his regular sun shots. Scott told him to climb the ladder to the machine gun post on the top of the airship. When there, a series of ‘Up a bit’ calls would get him skimming along in the sunlight on the top of the cloud. A neat bit of precision pilotage.

Everyone was happy with this apart from Major G H Cooke, the navigator. He needed to take his regular sun shots. Scott told him to climb the ladder to the machine gun post on the top of the airship. When there, a series of ‘Up a bit’ calls would get him skimming along in the sunlight on the top of the cloud. A neat bit of precision pilotage.

The route chosen was not a direct course, it was determined by pressure patterns. The Navy had strategically stationed HMS Renown and HMS Tiger in mid Atlantic and they sent regular weather reports to the R34. Lt Guy Harris, the airship’s meteorologist, used these to plot the position and movement of depressions knowing that they would be likely to find tailwinds to the north of a depression. Harris was also expected to give some assessment of wind speeds at different levels so that the ship could be flown at an altitude when the headwind was weakest.

The weather grew increasingly worse and they were often flying through storms when the drumming of the rain on the envelope was a deafening roar. The whole ship leaked and rivulets of water soaked everything. In contrast, in a rare fine spell, the off watch were able to relax in the sun on top of the ship, leaning against the tail fin and playing jazz records on their gramophone.

The first land spotted was an island off the coast of Newfoundland. It was 12.50 pm on 5th July, the fourth day of the voyage. They had crossed the Atlantic but there were still 1200 miles to go before they reached New York. Capt. Scott was worried about the petrol supply. There was no gauge – they had to dip all of the 80 tanks. There was rather less than 500 gallons left and they were fighting against the wind. Their most optimistic calculation said they would run out of fuel. The mood of the crew was in sharp contrast to the telegrams of congratulation that were already pouring in.

Scott radioed the US Navy to have a destroyer stand by to give them a tow if the fuel was exhausted before they reached Montauk air base on the eastern tip of Long Island where they could refuel. The Navy sent out two destroyers, Bancroft and Stevens. Major Fuller, one of a small RAF party which had been sent ahead to New York to help organise the ground handling of the airship, travelled to Boston in case R34 had to land there.

The airship crossed Nova Scotia and crept over the Bay of Fundy. They were surprised to be overtaken by a thunderstorm which developed behind them. The turbulent cloud formed round them and the ship pitched downwards, falling 700 feet. The chief engineer, Lt J D Shotter, was in the ship near the bow drogue hatch. He was knocked off his feet and slid along the walkway towards the open hatch. Only by jamming a boot against one of the girders was he able to avoid falling out of the ship. The men in the control car could see the whole framework flexing as the tail twisted from side to side. The silver lining in the storm was a strong tailwind. Scott had all of the near-empty tanks drained and the fuel transferred into one. He determined to press on to New York.

Their landing ground crept into view at 9.00 am on 6th July. Roosevelt Field at Mineola is on the western tip of Long Island, not far from where JFK Airport would be built where countless travellers have landed in the USA since that first arrival over 100 years ago.

The weather grew increasingly worse and they were often flying through storms when the drumming of the rain on the envelope was a deafening roar. The whole ship leaked and rivulets of water soaked everything. In contrast, in a rare fine spell, the off watch were able to relax in the sun on top of the ship, leaning against the tail fin and playing jazz records on their gramophone.

The first land spotted was an island off the coast of Newfoundland. It was 12.50 pm on 5th July, the fourth day of the voyage. They had crossed the Atlantic but there were still 1200 miles to go before they reached New York. Capt. Scott was worried about the petrol supply. There was no gauge – they had to dip all of the 80 tanks. There was rather less than 500 gallons left and they were fighting against the wind. Their most optimistic calculation said they would run out of fuel. The mood of the crew was in sharp contrast to the telegrams of congratulation that were already pouring in.

Scott radioed the US Navy to have a destroyer stand by to give them a tow if the fuel was exhausted before they reached Montauk air base on the eastern tip of Long Island where they could refuel. The Navy sent out two destroyers, Bancroft and Stevens. Major Fuller, one of a small RAF party which had been sent ahead to New York to help organise the ground handling of the airship, travelled to Boston in case R34 had to land there.

The airship crossed Nova Scotia and crept over the Bay of Fundy. They were surprised to be overtaken by a thunderstorm which developed behind them. The turbulent cloud formed round them and the ship pitched downwards, falling 700 feet. The chief engineer, Lt J D Shotter, was in the ship near the bow drogue hatch. He was knocked off his feet and slid along the walkway towards the open hatch. Only by jamming a boot against one of the girders was he able to avoid falling out of the ship. The men in the control car could see the whole framework flexing as the tail twisted from side to side. The silver lining in the storm was a strong tailwind. Scott had all of the near-empty tanks drained and the fuel transferred into one. He determined to press on to New York.

Their landing ground crept into view at 9.00 am on 6th July. Roosevelt Field at Mineola is on the western tip of Long Island, not far from where JFK Airport would be built where countless travellers have landed in the USA since that first arrival over 100 years ago.

Fuller, who was to have marshalled the ground handlers for the landing was in Boston. Major Jack Pritchard volunteered to take his place. But first, he had a wash, shaved, using hot water from one of the engine radiators and put on a decent uniform. Then he leapt into history as the first man to arrive in the Americas by air by parachuting to ground to supervise the landing.

R34 had flown 3600 miles in 108 hours 12 minutes and there were 140 gallons of fuel left in the tanks. That was enough for two hours at cruise power, say 100 miles.

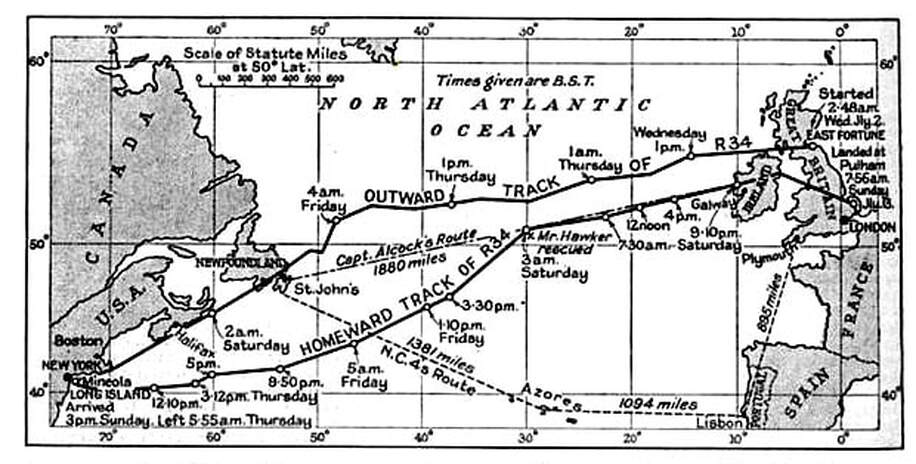

The map also shows the flight of the Curtiss NC-4 flying boat, 15–27 May

and Alcock and Brown’s Vimy 14-15 June.

R34 had flown 3600 miles in 108 hours 12 minutes and there were 140 gallons of fuel left in the tanks. That was enough for two hours at cruise power, say 100 miles.

The map also shows the flight of the Curtiss NC-4 flying boat, 15–27 May

and Alcock and Brown’s Vimy 14-15 June.

The airship was welcomed by a huge crowd, some on a grandstand which had been specially built. A band played ‘God Save the King’ and an army of pressmen and photographers interviewed anyone with the slightest connection with R34, including the rope pullers. The crew were invited to many more reception dinners than they could attend and the essential servicing of the ship was constantly interrupted by the questions of the eager visitors.

Although all were impressed by the sheer size of the airship – it was the first large rigid airship to be seen in America - there were contrary reactions. Grover Loening was an aircraft designer (one of his designs was an aeroplane which was carried by a submarine). He was surprised by ‘how un-rigid it really was. Close up one was astounded to see how the frame squeaked, bent and shivered with the cloth covering almost flapping in wind gusts… I was shocked at its flimsiness… frantically the crew and many others tugged and pulled on ropes and handrails to restrain the monster… .’

The airship was pulled down to the ground during the day and raised for mooring at night. There are many ways of mooring an airship and they are all problematic. The ship must be kept in balance, neither rising or sinking and it must be free enough to swing if the wind direction changes. During the war, the Germans had attached their Zeppelins to trolleys which could be moved about on rails. In later years the favourite, certainly at fixed bases, seemed to be mooring the nose to a fixed mast. There were of course advocates of small masts and of tall masts. Every method came with its own problems.

Although all were impressed by the sheer size of the airship – it was the first large rigid airship to be seen in America - there were contrary reactions. Grover Loening was an aircraft designer (one of his designs was an aeroplane which was carried by a submarine). He was surprised by ‘how un-rigid it really was. Close up one was astounded to see how the frame squeaked, bent and shivered with the cloth covering almost flapping in wind gusts… I was shocked at its flimsiness… frantically the crew and many others tugged and pulled on ropes and handrails to restrain the monster… .’

The airship was pulled down to the ground during the day and raised for mooring at night. There are many ways of mooring an airship and they are all problematic. The ship must be kept in balance, neither rising or sinking and it must be free enough to swing if the wind direction changes. During the war, the Germans had attached their Zeppelins to trolleys which could be moved about on rails. In later years the favourite, certainly at fixed bases, seemed to be mooring the nose to a fixed mast. There were of course advocates of small masts and of tall masts. Every method came with its own problems.

At Mineola there was of course no mast and Scott used a clever system with three wires attached to heavy blocks spaced out at the points of a large triangle. The wires were spliced to a central ring and could be adjusted to react to any wind change so it had to be constantly manned.

Even when the ship was hauled down for servicing and refuelling it was never resting on the ground. It was always held slightly lighter than air.

For three days the crew carried out maintenance on the ship and its engines (they were offered help but it was quicker and easier if they did the work themselves), they accepted as many invitations as they could, usually to dinners, and they fought off many offers of gifts, primarily because of the weight. (They did accept a gramophone from Thomas Edison, no less). An offer of $1000 for Wopsie was not accepted.

At a dinner on the evening of the 9th July, Scott was told of a forecast of high winds. He decided to leave at once. He collected the crew (well, stowaway Ballantyne was told to make his own way home) and the passenger, Lt. Col. W.N. Hensley of the U.S. Army. R34 lifted off at 11.54 that evening to rousing cheers taking with it a case of rum which had been pushed aboard at the last second. Scott had been asked to fly over New York. He had no idea how high the skyscrapers were so took the airship to 1500 ft and cruised through the turbulent air over the city. Searchlights played on and around they ship and the crowds who had gathered in the streets (at 1.00 am!) waved their farewell.

Progress was good. The following wind raised their groundspeed to 90 mph. Scott chased a couple of depressions to take advantage of the stronger westerlies on their southern flank. They were doing so well that Maitland changed their flight plan. They would celebrate their double crossing of the Atlantic by flying over London.

The next morning one of the engines in the rear car failed. One of the depressions rained on them and they were enveloped in depressing murk. There were other engine problems. One had to be shut down for two hours to have broken valve springs replaced. In another car the engineer slipped and fell against the clutch control. The engine raced and a con-rod broke before it could be shut down. Nevertheless they soon found themselves approaching land. It was the coast of island and happened to be very near the wireless station at Clifden where Alcock and Brown had landed. They were met by a small biplane which briefly flew alongside. As darkness fell, they crossed the English coast at Liverpool

For three days the crew carried out maintenance on the ship and its engines (they were offered help but it was quicker and easier if they did the work themselves), they accepted as many invitations as they could, usually to dinners, and they fought off many offers of gifts, primarily because of the weight. (They did accept a gramophone from Thomas Edison, no less). An offer of $1000 for Wopsie was not accepted.

At a dinner on the evening of the 9th July, Scott was told of a forecast of high winds. He decided to leave at once. He collected the crew (well, stowaway Ballantyne was told to make his own way home) and the passenger, Lt. Col. W.N. Hensley of the U.S. Army. R34 lifted off at 11.54 that evening to rousing cheers taking with it a case of rum which had been pushed aboard at the last second. Scott had been asked to fly over New York. He had no idea how high the skyscrapers were so took the airship to 1500 ft and cruised through the turbulent air over the city. Searchlights played on and around they ship and the crowds who had gathered in the streets (at 1.00 am!) waved their farewell.

Progress was good. The following wind raised their groundspeed to 90 mph. Scott chased a couple of depressions to take advantage of the stronger westerlies on their southern flank. They were doing so well that Maitland changed their flight plan. They would celebrate their double crossing of the Atlantic by flying over London.

The next morning one of the engines in the rear car failed. One of the depressions rained on them and they were enveloped in depressing murk. There were other engine problems. One had to be shut down for two hours to have broken valve springs replaced. In another car the engineer slipped and fell against the clutch control. The engine raced and a con-rod broke before it could be shut down. Nevertheless they soon found themselves approaching land. It was the coast of island and happened to be very near the wireless station at Clifden where Alcock and Brown had landed. They were met by a small biplane which briefly flew alongside. As darkness fell, they crossed the English coast at Liverpool

The troubles with the engines had forced Maitland to abandon the London flypast. He had not mentioned it in any of his signals to the Air Ministry or East Fortune so it was a simple matter of getting Scott to reset his course for Scotland. Then a signal from the Air Ministry was received at 10.00 am on 12th July instructing Scott to land at Pulham, the airship station in Norfolk some 15 miles south of Norwich. Maitland immediately queried this. He said that all the crew and their families gathering to meet to ship on its return home to East Fortune would be disappointed. He also pointed out that the forecast weather at Pulham was worse than that at East Fortune.. At 11.30 the Air Ministry bluntly confirmed the order. ‘Land at Pulham’.

No reason was given, then or afterwards. There were dark mutterings that the anti-airship lobby had succeeded in dampening the favourable publicity the R34 would receive after the successful conclusion of its momentous flight. In the view of the aggrieved crew, who had achieved the double crossing of the Atlantic they had, in turn, been double-crossed by the Air Ministry. Although there was much speculation the reason for the signal has remained a mystery.

No reason was given, then or afterwards. There were dark mutterings that the anti-airship lobby had succeeded in dampening the favourable publicity the R34 would receive after the successful conclusion of its momentous flight. In the view of the aggrieved crew, who had achieved the double crossing of the Atlantic they had, in turn, been double-crossed by the Air Ministry. Although there was much speculation the reason for the signal has remained a mystery.

It was early in the morning of Sunday 13th July when R34 circled the field at Pulham. Only two of the engines were working properly and Scott disguised this by having the others declutched to allow the propellers to rotate in the slipstream.

The news that the expected landing would be at Pulham had not been widely spread. ‘Rather tepid reception’ was one comment. The locals rushed to the field to see one of ‘their’ airships arriving and the band turned up, playing ‘See the Conquering Hero Comes.’ It was unfortunate that this was just as Scott realised that R34 was descending a little quickly and released a tankful of water. Bravely, the band played on.

R34 at Pulham. The old tank was used

to open the heavy shed doors.

The handlers caught the ropes and R34 was moored at 6.57 am, 75 hours after leaving New York. The whole journey totalled 7,420 miles at an average speed of 37.1 knots. The effect of the prevailing Westerly winds showed in the average speeds of the outward and homeward flights, 28.9 and 44.2 knots respectively,

What happened next:

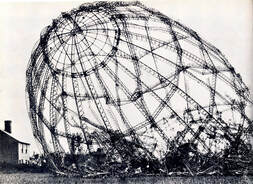

R34 went back to East Fortune for a refit then was transferred to Howden in Yorkshire. On 27 January, 1921 it was on a routine training flight over the North Sea. The weather turned nasty and the ship collided with the North Yorkshire moors, crunching the front of the control car and ripping off two engines. It bounced back into the air and limped home, being forced down to the ground in a strong wind. Temporarily moored for the night, the wind rose to gale force. The ship thrashed about. A gas bag was punctured and the hull too badly damaged for repair. Anything salvageable was removed and the remains sold for scrap.

Lieutenant Commander Zachary Landsdowne became captain of Shenandoah, America’s first airship (a copy of a Zeppelin, though using helium instead of hydrogen). It performed well until Sept 1925 when it was caught in a violent line squall and broke up. Lansdowne and 14 crew members died in the crash.

The Americans bought what was intended to be their second airship from Britain whilst it was still being built, R38. On completion it was being rushed through its tests and full control was applied when the ship was travelling at high speed. The hull split apart and most of the crew died, including Brig.Gen. Maitland and Major Pritchard.

Major George Herbert Scott retired from the RAF after the transatlantic flight and joined the staff at the Royal Airship Works, Cardington. He was on the investigation team after the accident to the R38 and did considerable work developing mooring masts. He was involved in several incidents and took some risks which led to his judgement being question. Although highly experienced he was not appointed captain of an airship but was aboard to ‘give advice’, said to be like an Admiral on his flagship. As such, he was on the R100 which repeated the R34’s double Atlantic crossing in 1930, during which he demonstrated his ‘press-on’ style of piloting when the R100 was damaged in a storm. He had a similar appointment on the R101and died in the crash at Beauvais.

The shed at Pulham was dismantled and re-erected at Cardington where it is available for hire by any passing film-maker.

The R101 crash ended Britain’s involvement with rigid airships and the US abandoned them too. Non-rigid ships continued to be built and America had a large fleet of ‘blimps’ which they used for coastal patrol. The end of rigid airships was signalled most famously by the burning Hindenburg at Lakehurst, NJ in 1937.