Howard Pixton

Britain's First Professional Test Pilot (May 2016)

In 1910 Howard Pixton was working as a mechanic and driver at a garage in Leek, Staffordshire. The news that Claude Grahame-White and Louis Paulhan had set off in a race from London to Manchester to win a £10,000 Daily Mail prize caught his attention. He was fascinated by flight and when he learned that Grahame-White had landed near Lichfield he dashed off with a group of passengers. A close-up view of the Farman biplane left him a little disappointed in the design and workmanship but more determined to get involved somehow in flying.

He despatched a series of letters to anyone would might help and learned that it would cost him £100, much more than he could afford, to learn to fly. His letter in response to an advert by A V Roe of Manchester brought the first positive response. Humphrey Roe was building aeroplanes at his works in Manchester for his brother, Alliott, now based in Brooklands. H V suggested that if Pixton offered his services to A V as a mechanic he might learn to fly. Pixton gladly handed over £30 (half of his total savings) to pay for any damage he caused to machines during training and set off for Brooklands.

He expected to see a hive of activity. Instead he found the place deserted. The ground inside the track has been roughly cleared though it was still bisected by the River Wey. In the distance was a line of black sheds. Pixton found the A V Roe shed. Roe was surprised to see Pixton, knowing nothing about him or his arrangements with H V. He insisted that his two triplanes were unsuitable for training but reluctantly allowed Pixton to stay.

Howard spent most of his time modifying Roe’s triplanes and repairing the damage after flights. Roe took him up for a brief hop but offered no instruction. Eventually he was allowed to take the older triplane and practise ‘rolling’. Naturally, he applied full power and soon found himself at 50ft. When a wing dropped he first applied the controls the wrong way but quickly corrected and landed safely.

He despatched a series of letters to anyone would might help and learned that it would cost him £100, much more than he could afford, to learn to fly. His letter in response to an advert by A V Roe of Manchester brought the first positive response. Humphrey Roe was building aeroplanes at his works in Manchester for his brother, Alliott, now based in Brooklands. H V suggested that if Pixton offered his services to A V as a mechanic he might learn to fly. Pixton gladly handed over £30 (half of his total savings) to pay for any damage he caused to machines during training and set off for Brooklands.

He expected to see a hive of activity. Instead he found the place deserted. The ground inside the track has been roughly cleared though it was still bisected by the River Wey. In the distance was a line of black sheds. Pixton found the A V Roe shed. Roe was surprised to see Pixton, knowing nothing about him or his arrangements with H V. He insisted that his two triplanes were unsuitable for training but reluctantly allowed Pixton to stay.

Howard spent most of his time modifying Roe’s triplanes and repairing the damage after flights. Roe took him up for a brief hop but offered no instruction. Eventually he was allowed to take the older triplane and practise ‘rolling’. Naturally, he applied full power and soon found himself at 50ft. When a wing dropped he first applied the controls the wrong way but quickly corrected and landed safely.

Although Roe had been flying his triplanes since 1909 it wasn’t until July 1910 that his flying was observed by Aero Club officials and he was granted his licence, No 18. He decided to attend a flying meeting at Blackpool. The carefully packed triplanes were loaded onto a railway truck and covered with a tarpaulin sheet. Sadly, the truck was coupled directly behind the engine and sparks set the tarpaulin alight. The aeroplanes, spares and luggage were completely destroyed. A hurried visit to the factory found enough components to build another triplane to get to the meeting.

Another trip was across the Atlantic to a meeting in Boston. Success was variable. Roe flew but his engine was unreliable and most ‘landings’ needed repairs, some major. The triplane’s components and spares were sold and Avro’s principal gain was just the experience.

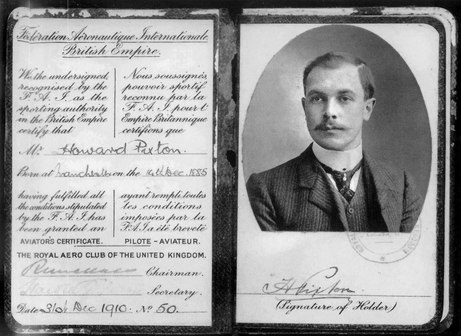

When he had the chance to fly Pixton soon showed that that he was becoming a competent pilot. He qualified for licence No 50 on the last day of the year and A V decided to change his volunteer status and pay him £2 per week. The £30 deposit had long since disappeared after a series of minor crashes and he suffered frequent arrivals in the sewage farm. (This was more a flooded field than the noxious lake depicted in the ‘Magnificent Men …‘ film).

Roe now flew less and less and Pixton dealt with the increasing number of pupils. A new biplane powered by a 35 hp Green engine arrived from Manchester and Pixton did the test flights. It proved to be Britain’s first successful tractor biplane. Pixton flew it in increasingly strong winds which deterred other pilots. Roe even entrusted him to take the newly- wed Mrs Roe as a passenger.

Roe now flew less and less and Pixton dealt with the increasing number of pupils. A new biplane powered by a 35 hp Green engine arrived from Manchester and Pixton did the test flights. It proved to be Britain’s first successful tractor biplane. Pixton flew it in increasingly strong winds which deterred other pilots. Roe even entrusted him to take the newly- wed Mrs Roe as a passenger.

The AVRO biplane was attracting many new trainees but, with only one aeroplane available the training list was overcrowded and many frustrated students were leaving. Howard was working hard and neither his pay nor the company’s profits were keeping up with his work load. Reluctantly he told the Roes that he was going to leave. In June 1911 they parted on good terms.

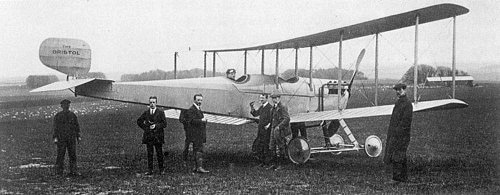

Bristol were pleased to take Pixton to run their Brooklands flying school and offered him £5 per week. He found the Boxkite required a very different flying technique. Normally it was flown only in calm conditions but Howard enhanced his reputation as a ‘strong wind’ flier by a demonstration one day when no-one else flew. The wind was reported as blowing at 30– 40 mph.

Bristol operated the largest flying school in the country at Larkhill near Salisbury and Pixton was transferred there in August. Many of the pupils were military men who had to pay for their own tuition if they hoped to join the Air Battallion. Pixton taught many officers whose names would become famous in the RFC. The oldest, at 49, by some margin, was Brig. Gen Henderson who became the first Commandant of the RFC on the outbreak of war.

Bristol operated the largest flying school in the country at Larkhill near Salisbury and Pixton was transferred there in August. Many of the pupils were military men who had to pay for their own tuition if they hoped to join the Air Battallion. Pixton taught many officers whose names would become famous in the RFC. The oldest, at 49, by some margin, was Brig. Gen Henderson who became the first Commandant of the RFC on the outbreak of war.

As Britain’s largest manufacturer of aeroplanes, Bristol looked to expand their market overseas. They recruited Pierre Prier, a French designer who had worked with Bleriot. He produced a two-seat monoplane which was expected to attract military orders. Pixton did some of the test flights on the Bristol-Prier and was asked to demonstrate it in Europe. It was exhibited at the 3rd International Air Show in Paris after which Pixton took it to Madrid to fly it before senior army officers and the king. An order for several machines followed.

Next, he went to Germany to demonstrate the Prier at Döberitz near Berlin. The Kaiser was there though, unlike his reception in Spain, Howard was not presented to him. The wind was strong and no one expected him to fly. Pixton thought it would be a good opportunity to demonstrate the capabilities of the aeroplane. The take-off was spectacular but he found the handling difficult in the gusty conditions. He badly mis-judged his approach to land, hit the ground hard and bounced up. It was prudent to open the throttle and go round again. Happily the second approach resulted in a good landing. He was pleased to learn that the Germans thought his first hard arrival had been deliberate to show the strength of the undercarriage. Again, orders followed the visit.

Pixton paid another visit to Germany shortly afterwards to the Deutsche Bristol Werke at Halberstadt where Priers and Boxkites were being produced. He formed a flying school and trained the first six German officers.

In Germany and Britain a total of 34 Bristol-Prier monoplanes were produced.

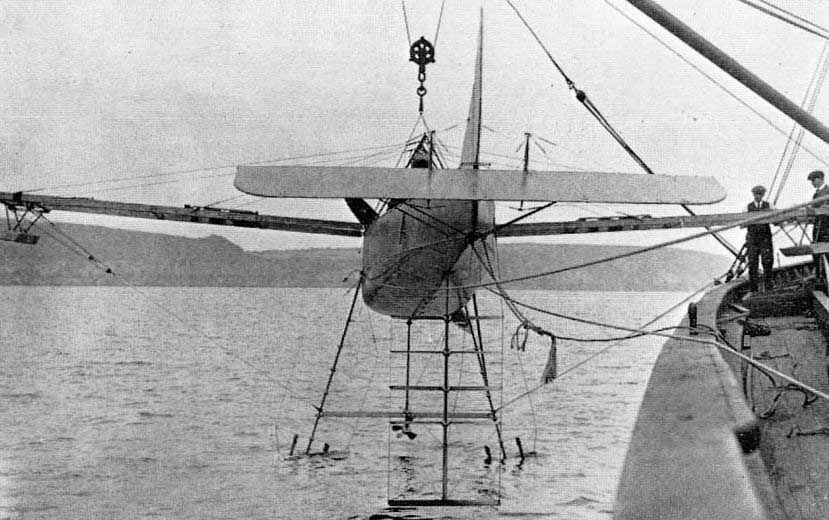

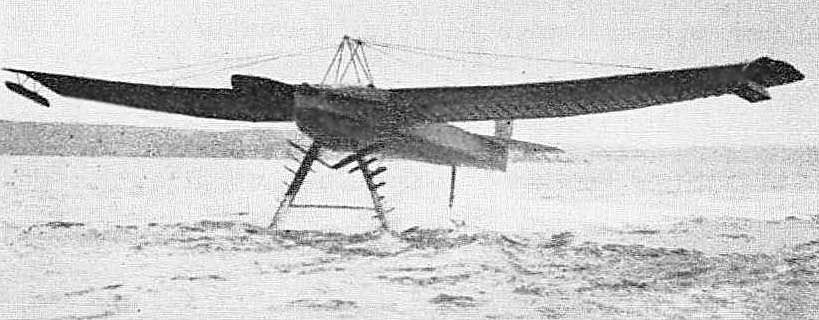

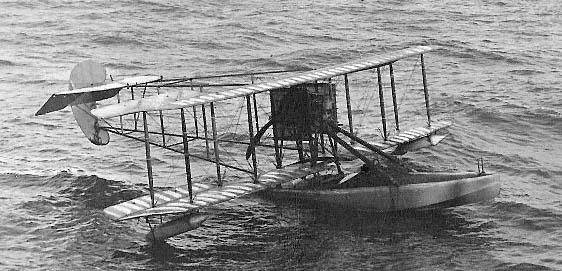

Between his European tours Howard became involved with the experimental work of one of his Larkhill pupils. Dennistoun Burney was a naval lieutenant with ideas. He produced a design for a hydroplane glider to be towed into the air by a ship and used as a spotting kite. Then he added an engine to drive both an airscrew and water propellers through separate clutches.

Bristol built his aero/hydro/plane in secret and it was taken to Milford Haven for testing. The engine was buried in a leaking fuselage and getting it to start was the first problem. Burney then thought of towing it until it was up on its hydrofoils. Conveniently, his father was an admiral and promptly provided a destroyer so that the experiments could continue.

Bristol built his aero/hydro/plane in secret and it was taken to Milford Haven for testing. The engine was buried in a leaking fuselage and getting it to start was the first problem. Burney then thought of towing it until it was up on its hydrofoils. Conveniently, his father was an admiral and promptly provided a destroyer so that the experiments could continue.

For three weeks, Howard endured his soakings trying control the unstable craft but they never got it out of the water. He was quite pleased. He didn’t relish the thought of alighting with only the buzzing little water propellors to counteract the drag of the hydrofoils and prevent a nose over.

Burney failed with this design but went on to develop the hydrovane for minesweeping and later become Managing Director of the Vickers subsidiary that built the R100.

Burney failed with this design but went on to develop the hydrovane for minesweeping and later become Managing Director of the Vickers subsidiary that built the R100.

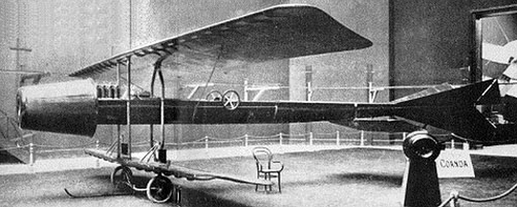

The Bristol Flying School at Larkhill took on a new and distinguished pupil. Prince Cantecuzene of Romania arrived with a small group of officers to learn to fly with Pixton. This might have been the trigger which led to Bristol employing a new designer from Romania, Henri Coanda. He happened to be the son of the Minister for War but his qualification was his design skills. He had done some pioneering research into the flow of air over curved surfaces and in 1910 he built an extraordinary biplane powered by a ducted fan.

The announcement of the Military Aeroplane Trials to be held at Larkhill came at very short notice. They were to be held in August 1912, only two months ahead. The designer of the successful Prier monoplane had returned to France so, with insufficient time to produce a new design, Bristol asked Coanda to modify the Prier. The trials were for two-seat aeroplanes which could achieve set speeds, altitude and duration. In addition, they should be able to land and take off from a cultivated field and bizarrely, get into the field in a standard railway container which could pass through a farm gate.

There were 32 entrants but only 20 got to Larkhill in time for the competition. Bristol entered four machines, two biplanes designed by Gordon England and two Coanda monoplanes. Initially Howard Pixton was to fly one of the biplanes until a Coanda suffered a crash after engine failure and its pilot walked out. Pixton was asked to take over.

There were 32 entrants but only 20 got to Larkhill in time for the competition. Bristol entered four machines, two biplanes designed by Gordon England and two Coanda monoplanes. Initially Howard Pixton was to fly one of the biplanes until a Coanda suffered a crash after engine failure and its pilot walked out. Pixton was asked to take over.

It was unfortunate that the August of 1912 was one of the wettest on record and most of the entrants failed to take off from the muddy ploughed field. The exception was Samuel Cody. He had entered his new No IV monoplane for the trials but that had crashed. (It collided with a cow and Cody’s defence that the cow had ‘committed suicide’ failed. He had to pay the farmer £18 compensation). He transferred the engine to his old ‘cathedral’ biplane and managed the ploughed field landing and takeoff before the rains came.

Pixton recorded the best range, 420 miles, and did particularly well in the speed and the ‘wind flying’. The tests required a flight in a wind averaging 25 mph and Howard and his passenger flew in gusts recorded at 47 mph, acclaimed as a new ‘world record’.

Overall, Cody’s No VA biplane was declared the winner. There was no second place. Pixton’s Coanda shared third place with a Deperdussin. The War Office bought two each of the three machines for operational tests. Sadly, one of the Coandas crashed when a quick-release lever on a bracing wire became detached in flight. The two occupants were killed and temporarily the War Office banned monoplanes.

The ban didn’t affect overseas sales and Coanda was keen to show his monoplane at home in Romania. So it was another long trip for Pixton. They arrived in a period of military manoeuvres and were given a royal – and very senior military – reception. The Coanda performed well and Pixton had many eager passengers. The visit produced orders for ten machines with more to follow.

Back in England, Howard found time to marry Maude Haslam. Whether it was Howard or Maude who showed the greater dedication, part of the honeymoon was spent at Brooklands, Larkhill and Hendon, the second part was in Italy. Flown in a wonderful setting in sight of the snow-covered Alps, the demonstrations of the Coanda produced an order for twenty machines from Bristol with a production line to be set up for Caproni to build more.

Just a month later, Howard started 1913 with a second visit to Spain. Once again, he was warmly received by the king and queen with other members of their family. A guest was Prince Leopold of Battenburg, a grandson of Queen Victoria and he asked for a flight with Pixton. The press at home made a big fuss of this, the first member of the British royal family to fly. They didn’t mention that another of Howard’s passengers was a Spanish royal, King Alfonso himself, who was already a qualified pilot.

Returning to a more settled life Howard came back to Larkhill as Manager of the Flying School. Bristol was now one of the worlds’ largest aircraft manufacturers with a staff of over 400. Their machines were highly regarded and they had a full order book. Many of the pupils at Larkhill were sponsored by foreign governments and they also worked in the factory as their own licensed production lines were established.

Early in 1913 Pixton witnessed a number of fatal crashes, one on a gusty day when a wing folded and another when an engine caught fire in the air. Shortly afterwards came the news of Samuel Cody’s death. Cody was the first man to fly in England, a very experienced pilot and a great friend of Howard’s. These events had a marked effect on Howard’s attitude to flying and he became determined to do all he could to make flying safer.

Overall, Cody’s No VA biplane was declared the winner. There was no second place. Pixton’s Coanda shared third place with a Deperdussin. The War Office bought two each of the three machines for operational tests. Sadly, one of the Coandas crashed when a quick-release lever on a bracing wire became detached in flight. The two occupants were killed and temporarily the War Office banned monoplanes.

The ban didn’t affect overseas sales and Coanda was keen to show his monoplane at home in Romania. So it was another long trip for Pixton. They arrived in a period of military manoeuvres and were given a royal – and very senior military – reception. The Coanda performed well and Pixton had many eager passengers. The visit produced orders for ten machines with more to follow.

Back in England, Howard found time to marry Maude Haslam. Whether it was Howard or Maude who showed the greater dedication, part of the honeymoon was spent at Brooklands, Larkhill and Hendon, the second part was in Italy. Flown in a wonderful setting in sight of the snow-covered Alps, the demonstrations of the Coanda produced an order for twenty machines from Bristol with a production line to be set up for Caproni to build more.

Just a month later, Howard started 1913 with a second visit to Spain. Once again, he was warmly received by the king and queen with other members of their family. A guest was Prince Leopold of Battenburg, a grandson of Queen Victoria and he asked for a flight with Pixton. The press at home made a big fuss of this, the first member of the British royal family to fly. They didn’t mention that another of Howard’s passengers was a Spanish royal, King Alfonso himself, who was already a qualified pilot.

Returning to a more settled life Howard came back to Larkhill as Manager of the Flying School. Bristol was now one of the worlds’ largest aircraft manufacturers with a staff of over 400. Their machines were highly regarded and they had a full order book. Many of the pupils at Larkhill were sponsored by foreign governments and they also worked in the factory as their own licensed production lines were established.

Early in 1913 Pixton witnessed a number of fatal crashes, one on a gusty day when a wing folded and another when an engine caught fire in the air. Shortly afterwards came the news of Samuel Cody’s death. Cody was the first man to fly in England, a very experienced pilot and a great friend of Howard’s. These events had a marked effect on Howard’s attitude to flying and he became determined to do all he could to make flying safer.

Although the monoplane ban was soon lifted, Bristol though it prudent to concentrate on biplanes and Coanda’s monoplane quickly acquired an upper wing which, happily, improved its performance.

Still living in Romania Coanda was producing designs for Bristol and a new prototype arrived at Larkhill for testing

Pixton was not entirely happy with the new machine and thought it tail-heavy. He got his engineers to modify the tail unit. Somehow, Coanda heard of this and telephoned to insist that there should be no modification of his design. Soon, one of the company’s directors, Stanley White, became involved and, in a heated three-way telephone conversation, took Coanda’s part and told Pixton to fly the machine as it was. Reluctantly, Howard said he would have to resign and his highly successful career at Bristol’s came to a sudden end. (Later it turned out that Howard proved to have been right but, by then, it was too late).

Howard knew Sir Thomas Sopwith well. Although he was an experienced pilot, he was concentrating on construction in his Kingston factory. Harry Hawker was his pilot and he was planning to go back home to Australia. Sopwith was very happy for Pixton to take his place.

Howard knew Sir Thomas Sopwith well. Although he was an experienced pilot, he was concentrating on construction in his Kingston factory. Harry Hawker was his pilot and he was planning to go back home to Australia. Sopwith was very happy for Pixton to take his place.

Howard’s first job was to deliver a Batboat to the Navy. It was Britain’s first amphibian and Hawker had won prizes with it. Pixton greatly enjoyed taxying through the shipping in the Solent and found the BatBoat ‘delightful to fly.

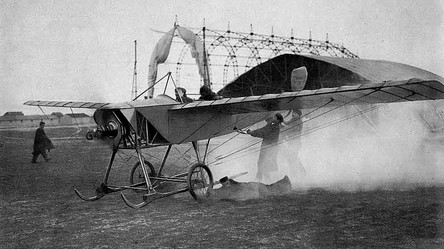

Howard was introduced to the Sopwith Scout. A tiny 2-seater (span 25’ 6”, length 20’) it caused a sensation with its astonishing speed. It acquired the nick-name Tabloid because it reminded people of a pill produced by Burroughs Wellcome. They protested, so the name was never used officially but it stuck with the public. Howard flew a single-seat version in several races. It quickly gained a reputation which encouraged such severe handicapping that it never managed to win any races. Nevertheless, just three weeks before the race was due to be held in Monaco on 20 April, 1914 Sopwith decided to enter it for the prestigious Schneider Trophy

The first race the previous year had been ‘something of a fiasco’. It was won by a Deperdussin, the only one of four entries to finish. The 1914 race promised to be very different. There were entries from France, Germany, Switzerland and America. The course was a closed circuit of 150 miles, during which there should be two ‘alightings’ on the water. Competitors were allowed only one attempt at any time between 8.00 am and sunset.

On the 1st April, Pixton took to the water (the Solent) in the Tabloid which had been hurriedly fitted with a wide single float. It quickly became evident that the float had been fitted too far aft. As soon as the throttle was opened, the float dug in and the Tabloid tipped onto its nose. Howard was catapulted out into the cold water. They had neglected to bring a boat so Howard swam ashore and the Tabloid drifted off into the Solent with its tail in the air. It was the next day, at low tide, before they could retrieve it and take it back to Kingston to dry out.

On the 1st April, Pixton took to the water (the Solent) in the Tabloid which had been hurriedly fitted with a wide single float. It quickly became evident that the float had been fitted too far aft. As soon as the throttle was opened, the float dug in and the Tabloid tipped onto its nose. Howard was catapulted out into the cold water. They had neglected to bring a boat so Howard swam ashore and the Tabloid drifted off into the Solent with its tail in the air. It was the next day, at low tide, before they could retrieve it and take it back to Kingston to dry out.

The float was sawn into two, mounted further aft and the Tabloid was taken down to the Thames for testing. This time, it sat well on the water. At the last minute, before Pixton could take off, officials of the Thames Conservancy hurried up to forbid any flying.

The Tabloid was dismantled again and taken next day to the Thames below Teddington Lock where the Port of London Authority had given permission to fly. Finally, the Tabloid rose from the water. A misfiring engine limited the flight to just 3 miles. Even so, the little seaplane had shown its potential by reaching 85 mph.

The Tabloid was dismantled again and taken next day to the Thames below Teddington Lock where the Port of London Authority had given permission to fly. Finally, the Tabloid rose from the water. A misfiring engine limited the flight to just 3 miles. Even so, the little seaplane had shown its potential by reaching 85 mph.

The team arrived at Monaco four days before the race, assembled the Tabloid, finished cleaning the rust off the engine and looked forward to some serious testing. Unfortunately, another arrival was the strong mistral wind which grounded all the competitors until the day before race.

Pixton and his crew got up early and managed to get in a few laps, practising tight turns round the four buoys of the course.

After ten minutes, he alighted. Some bracing wires needed to be strengthened and the propeller was changed. The fuel consumption of the 100 hp Monosoupape had not been tested so a just-in-case 6 gallon tank was lashed into the cockpit if it should be needed to complete the 172 miles of the 28 lap course.

Pixton and his crew got up early and managed to get in a few laps, practising tight turns round the four buoys of the course.

After ten minutes, he alighted. Some bracing wires needed to be strengthened and the propeller was changed. The fuel consumption of the 100 hp Monosoupape had not been tested so a just-in-case 6 gallon tank was lashed into the cockpit if it should be needed to complete the 172 miles of the 28 lap course.

The Tabloid was overshadowed by the strong French competition, all with 160 hp engines. Three large Nieuport monoplanes looked strong and the hot favourite was Roland Garros in his Morane, proudly carrying Race No 1.

The Swiss entry was a French-designed FBA flying boat, Race No 7, flown by M. Burri. Two Americans were flying a Nieuport and a Curtiss biplane and neither of the German entries had arrived, having crashed before the race.

On race day, the two Frenchmen were first to take off, followed soon by Burri. Pixton noted that the Nieuports looked sluggish on the water and seemed to be flying rather slowly. He was surprised by their racing technique, both flying very high and performing flat skidding turns.

On race day, the two Frenchmen were first to take off, followed soon by Burri. Pixton noted that the Nieuports looked sluggish on the water and seemed to be flying rather slowly. He was surprised by their racing technique, both flying very high and performing flat skidding turns.

Realising that he had a good chance of winning Howard was airborne in 15 minutes. At the end of the first lap he quickly performed his two alightings as high-speed touch-and-goes. His time for the first lap was half that of the French monoplanes and he astonished the crowd with his tight turns close to the pylons, banking at 60º – 70º.

The two French pilots were both having problems – the rear cylinders of their twin-row Gnome engines were overheating. They retired on their 17th and 18th laps. Garros watched in dismay. There seemed to be little point in taking off to try to beat the speedy Tabloid.

The two French pilots were both having problems – the rear cylinders of their twin-row Gnome engines were overheating. They retired on their 17th and 18th laps. Garros watched in dismay. There seemed to be little point in taking off to try to beat the speedy Tabloid.

Each of the 28 laps took a few seconds over 4 minutes and Howard kept count by tearing off little squares of numbered papers he had pinned to the panel. Then, on the 15th lap, the engine misfired. Pixton climbed a little in case he had to manoeuvre to land into wind if the engine failed. For six laps the occasional misfire slowed the Tabloid until the engine settled down and resumed its smooth running.

Pixton had clearly won the Trophy and no-one could beat him. He was warmly congratulated by Jacques Schneider, Thomas Sopwith and the many officials waiting to greet him. He and Sopwith were amused to see in the background that the Tabloid was being examined and measured by a group of French designers. Pixton’s top speed in the race had been 93 mph and the average was 86.78. (The misfiring had been caused by a broken cam so the second half of the race had been flown on eight cylinders). It was the first international win by any British aeroplane and the Tabloid had set a 300 km World Seaplane Record, a remarkable achievement in view of the minimal and hurried preparation.

It was nearly noon when not-in-a-hurry Burri landed as the only other finisher - average speed 51 mph. In the afternoon Garros handed over his Morane to Maurice Prévost, the 1913 winner of the Trophy, in a last desperate attempt to fly for the honour of France. After one lap he made his first compulsory landing and broke his propeller. Still, a small degree of honour could be salvaged - the engines of the two aeroplanes which completed the course were French.

Back in England, the popular press took scant notice of the Schneider Trophy but the aviation magazines gave due praise, echoed by the many guests at the grand luncheon hosted by the Royal Aero Club. In light of this reception, Howard was rather surprised to be tackled by the manager of Brooklands for ‘the dangerous nature’ of his flying. The Home Office had appointed special inspectors to visit flying grounds to look out for dangerous flying and he didn’t want Brooklands to be closed down.

Pixton went back to work testing and delivering aeroplanes, mostly Tabloids ordered by the War Office but also a larger version of the Bat Boat for Germany. He was looking forward to flying a Bat Boat in the Daily Mail Round Britain Seaplane Race, due to start on 10 August. It was not to be. All such events were cancelled when war was declared on 4th August and all civilian flying was prohibited.

It was nearly noon when not-in-a-hurry Burri landed as the only other finisher - average speed 51 mph. In the afternoon Garros handed over his Morane to Maurice Prévost, the 1913 winner of the Trophy, in a last desperate attempt to fly for the honour of France. After one lap he made his first compulsory landing and broke his propeller. Still, a small degree of honour could be salvaged - the engines of the two aeroplanes which completed the course were French.

Back in England, the popular press took scant notice of the Schneider Trophy but the aviation magazines gave due praise, echoed by the many guests at the grand luncheon hosted by the Royal Aero Club. In light of this reception, Howard was rather surprised to be tackled by the manager of Brooklands for ‘the dangerous nature’ of his flying. The Home Office had appointed special inspectors to visit flying grounds to look out for dangerous flying and he didn’t want Brooklands to be closed down.

Pixton went back to work testing and delivering aeroplanes, mostly Tabloids ordered by the War Office but also a larger version of the Bat Boat for Germany. He was looking forward to flying a Bat Boat in the Daily Mail Round Britain Seaplane Race, due to start on 10 August. It was not to be. All such events were cancelled when war was declared on 4th August and all civilian flying was prohibited.

The rate of production of Tabloids was too slow to keep Howard fully occupied so he joined the newly created Aeronautical Inspection Department at Farnborough, testing all air-delivered types of machines and new prototypes before orders were placed. As one of the few regular pilots at the AID, Pixton was made a Captain in the RFC. His work took him all over the country and occasionally to France. Inevitably, he had his share of ‘incidents’ but believed he came closest to death on the ground with an Avro 504. He offered to help when its engine was being particularly difficult to start. He was turning the prop for another swing when it burst into life and he overbalanced, luckily falling clear of the spinning prop. As a result of this it became standard practice that ignition switches were mounted outside the cockpit in view of the prop swinger and the usual similar sounding calls of ‘on’ and ‘off’ were replaced with clearer ‘switches off’ and ‘contact’.

After the end of the war, Pixton retired from what was now the RAF with over 3,500 hours in over 80 different types of aeroplane.

After the end of the war, Pixton retired from what was now the RAF with over 3,500 hours in over 80 different types of aeroplane.

He re-joined his original employer, Avro, who had set up pleasure-flight operations in several holiday resorts in Lancashire. Pixton started flying from Windermere in Avro 504s fitted with floats. In July of 1919 he carried newspapers from there to the Isle of Man, the first commercial air link to the island. Passengers could join these flights for 10 guineas each.

The following year the service re-started and pleasure flights from the beach at Douglas were also on offer. There were complaints, of course, and a petition signed by 20 people got the flights cancelled..

The following year the service re-started and pleasure flights from the beach at Douglas were also on offer. There were complaints, of course, and a petition signed by 20 people got the flights cancelled..

Pixton clearly enjoyed the Isle of Man - he retired

there in 1932. His aviation career was not entirely

over because he served again with the AID in WWII.

Retiring again at the age of 60 he went back to the

IOM. He died aged 87 in 1972 and is buried on the

island at Jurby.