Under the Bridge Fliers (Mar 2017)

Display pilots fly to show their aeroplanes to the crowd and an essential component of any display programme is the high (or low) speed pass, as low and as close to the crowd as possible. The pilots enjoy it too. They don’t really need spectators to get a thrill from skimming the earth – in fact they seek out lonely and unregulated areas to have most fun with that extra thrilling element of risk. And if there’s something they can fly under, or through, it’s almost irresistible.

The Forth Bridge has been threaded by many pilots flying from Turnhouse when it was an RAF station, the Golden Gate bridge near San Francisco has enough room for multiple loops to be performed round it and Brunel's bridge over the Clifton Gorge at Bristol has shown that failing to get the approach and clearance wrong can be fatal. Most under-the–bridge flying is risky and illegal, of course, unless the film makers you’re working for get permission.

‘The Blue Max’ was made in Ireland where the disused railway viaduct at Fermoy was available for shooting one of the highlights of the film. The pilot chosen to fly under the arches was Derek Piggott (who also flew the Boxkite in ‘Those Magnificent Men’). With time to practise getting it right he started by a dive and pass over two marks on the airfield showing the width of the bridge. There were also two scaffolding poles on the far side of the markings, so positioned that when they were lined up on the approach, the Triplane passed between the bridge marks.

The poles were then moved to line up with the real bridge and Derek practised flying over the bridge. When this was consistently accurate he flew under the bridge, first through the large span, no fewer than15 times, then 17 times through the narrower gap, with just 4 ft. of clearance from each wing tip. The last two runs were made under time pressure in a gusting crosswind. The resulting film, taken from several angles, was spectacular and a memorable demonstration of the skill needed to perform this dangerous manoeuvre.

It was as early as 1909 when Frank McClean demonstrated the capabilities of his Short seaplane by flying through Tower Bridge. He had an appointment in town and decided to fly there from the Isle of Sheppey. After Tower Bridge he flew close to the water under the other bridges on the way to Westminster, where he alighted.

On his return home the following day the tide had risen and the police made him taxi back downstream until he was clear of the bridges and could take off.

During WWI, flying through bridges was rife, almost a rite-of-passage for airmen. Tower Bridge had its share as this a bit of video shows - http://www.britishpathe.com/video/tower-bridge-3/query/01362000.

One unusual under-the–bridge event was the case of what must surely be the only airship ever to attempt this feat. Based at RAF Anglesey were SSZ non-rigid airships – blimps. These measured 143 feet in length and 47 feet from the top of the envelope to the keel. The squadron was holding a party to celebrate the armistice when the CO, Major Tommy Elmhirst (later Air Marshal Sir Thomas . . ) was challenged by a guest, RN Captain Gordon Campbell VC (later to become a Vice-Admiral and MP) to fly one of his blimps under the Menai Bridge. Elmhirst naturally said of course he would, provided Campbell came along as observer

One unusual under-the–bridge event was the case of what must surely be the only airship ever to attempt this feat. Based at RAF Anglesey were SSZ non-rigid airships – blimps. These measured 143 feet in length and 47 feet from the top of the envelope to the keel. The squadron was holding a party to celebrate the armistice when the CO, Major Tommy Elmhirst (later Air Marshal Sir Thomas . . ) was challenged by a guest, RN Captain Gordon Campbell VC (later to become a Vice-Admiral and MP) to fly one of his blimps under the Menai Bridge. Elmhirst naturally said of course he would, provided Campbell came along as observer

A rope dangled from the bridge measured the gap at low tide as 53 feet, giving the airship a vertical clearance of just 6 feet, a sobering result. Elmhirst realised that his alcohol-induced acceptance of the challenge was not going to be easy. As soon as suitable weather and low tide coincided, the co-conspirators, Elmhirst, Campbell and a mechanic sworn to secrecy, set off in SSZ 73 and headed for the straits.

The view of the bridge overhead was completely obscured by the envelope as they approached at a stately 40 mph, sufficiently fast to make the controls effective and so maintain precise height control. They lowered a sandbag on a rope so that it was exactly 3 feet below the keel and with the sandbag bouncing along the surface of the water, the blimp surfed safely under the bridge.

After the end of the war aviation activity collapsed but Tower Bridge remained a magnet for those still flying. In 1919, Australian Flt Lt Sidney Pickles was flying a Fairey Seaplane along the Thames at 1000 ft. He couldn’t resist diving down to thread through the bridge at 120 mph. Immediately afterwards, flying under the bridge was outlawed.

The view of the bridge overhead was completely obscured by the envelope as they approached at a stately 40 mph, sufficiently fast to make the controls effective and so maintain precise height control. They lowered a sandbag on a rope so that it was exactly 3 feet below the keel and with the sandbag bouncing along the surface of the water, the blimp surfed safely under the bridge.

After the end of the war aviation activity collapsed but Tower Bridge remained a magnet for those still flying. In 1919, Australian Flt Lt Sidney Pickles was flying a Fairey Seaplane along the Thames at 1000 ft. He couldn’t resist diving down to thread through the bridge at 120 mph. Immediately afterwards, flying under the bridge was outlawed.

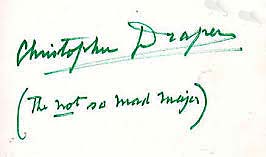

The law was unbroken until 1931 when the ‘Mad Major’ came to public notice. Christopher Draper was 17 when Bleriot flew the Channel. Inspired by this he learned to fly. He took a short-service commission with the Navy in January 1914. A fellow student on his course at the Central Flying School was one Hugh Dowding. When war broke out, Draper was a Flight Lieutenant based in Dundee. Naturally, he flew his seaplane under the Tay Bridge. Although he was assessed as a brilliant pilot he was considered poor at discipline and not suited to command. Nevertheless, by 1918 he was CO of No. 8 Squadron, RNAS. When this was absorbed into the newly-formed RAF as 208 Sqn and Draper’s rank changed to Major he continued to wear his naval uniform.

One morning, he ‘accidentally’ flew under a bridge in full view of a large body of troops. They cheered loudly, so he repeated the feat as often as he could and acquired the nickname ‘the mad Major’. Ending the war with a DSC and Croix de Guerre he became a test pilot for BAT, briefly re-joined the RAF to lead the aerobatic team at the 1921 Air Pageant and then resigned to earn what he could from stunt flying and film work.

One morning, he ‘accidentally’ flew under a bridge in full view of a large body of troops. They cheered loudly, so he repeated the feat as often as he could and acquired the nickname ‘the mad Major’. Ending the war with a DSC and Croix de Guerre he became a test pilot for BAT, briefly re-joined the RAF to lead the aerobatic team at the 1921 Air Pageant and then resigned to earn what he could from stunt flying and film work.

In 1931, out of work and broke, he became incensed by the Government’s bad treatment of war veterans and dreamed up a public protest. He planned to fly through 14 of London’s bridges in a borrowed Puss Moth. Bad weather intervened and Draper was restricted to flying through Tower Bridge, then turning round to fly through it again and duck under Westminster Bridge. It was sufficient to get him the publicity he wanted and also an appearance in court. He was bound over for 12 months – a light punishment.

In 1931, out of work and broke, he became incensed by the Government’s bad treatment of war veterans and dreamed up a public protest. He planned to fly through 14 of London’s bridges in a borrowed Puss Moth. Bad weather intervened and Draper was restricted to flying through Tower Bridge, then turning round to fly through it again and duck under Westminster Bridge. It was sufficient to get him the publicity he wanted and also an appearance in court. He was bound over for 12 months – a light punishment.

It was twenty years before Tower Bridge was violated again. In 1951, Frank Miller, a Chingford chemist, took his 13 year old son for a flight in his Auster. There below them was the bridge which tempted even the non-pilot. The lad asked his Dad to fly through it. Frank said ‘No’, he’d be fined. When the boy offered the entire contents of his piggy-bank Frank could no longer refuse. As he’d forecast, he duly appeared in court and Major Draper came along as an interested spectator. Frank was fined £100, in which the piggy-bank’s 35 shillings made but a small dent.

This event might have re-awakened an old urge in Christopher Draper’s mind. Since his flight through the bridge he had done some film work, acting as well as flying, and following a visit to Germany, had been recruited as a double agent. In 1939, he rejoined the Navy, ending the war as a Squadron Commander flying Walruses and Swordfish on anti-submarine work in West Africa. Post-war, he drifted again and by 1953, he was desperate for a job. Still upset by the treatment of veterans he thought a public demonstration might produce something.

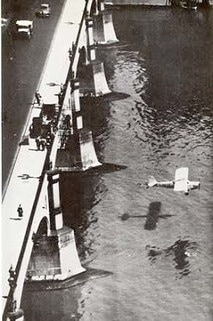

Here he is, on 5th May, 1953, aged 61, standing by the Auster he hired from the club at Broxbourne. His plan was to fly through 18 bridges, starting with Tower Bridge. The clearances were less than 50 feet and often there was little space to line up with the next arch or to avoid the occasional ship. In the event, tricky crosswinds caused him to fly over three bridges but the others were all ducked under successfully.

Here he is, on 5th May, 1953, aged 61, standing by the Auster he hired from the club at Broxbourne. His plan was to fly through 18 bridges, starting with Tower Bridge. The clearances were less than 50 feet and often there was little space to line up with the next arch or to avoid the occasional ship. In the event, tricky crosswinds caused him to fly over three bridges but the others were all ducked under successfully.

|

It just happened that Big Ben was being repaired and tidied up for the Queen’s Coronation and the Daily Mail had sent a photographer. The chance for his best shot of the day fell at his feet. Inevitably, the Major appeared in court charged with ‘low flying in an urban area’. The sympathetic magistrate accepted his promise to behave for the next 12 months and made him pay only 10 guineas court costs. He kept his licence active until 1964. |

The year after Draper’s transgression a visitor from Texas, Gene Thompson, flew another Auster through Tower Bridge. The reaction of the authorities is not recorded.

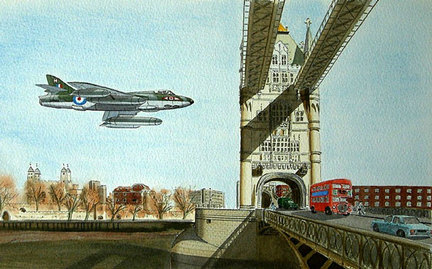

The Bridge flight which is best remembered and made the most impact was done on an impulse. Flt Lt Alan Pollock was incensed by the Wilson government’s failure to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the RAF with a flypast over London. With four other Hunters he was scheduled to return to his home base at West Raynham from Tangmere on 5th April 1968. The direct route would pass over London and Pollock quietly broke away from the formation and headed for the Houses of Parliament. As Big Ben was striking noon he circled Parliament three times, effectively interrupting a debate. Passing the RAF Memorial he saw Tower Bridge ahead and, with just ten seconds to spare, decided to fly through rather than over it. He stayed a little high to avoid a London bus crossing the bridge and was concerned that the upper walkway might remove his fin.

The Bridge flight which is best remembered and made the most impact was done on an impulse. Flt Lt Alan Pollock was incensed by the Wilson government’s failure to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the RAF with a flypast over London. With four other Hunters he was scheduled to return to his home base at West Raynham from Tangmere on 5th April 1968. The direct route would pass over London and Pollock quietly broke away from the formation and headed for the Houses of Parliament. As Big Ben was striking noon he circled Parliament three times, effectively interrupting a debate. Passing the RAF Memorial he saw Tower Bridge ahead and, with just ten seconds to spare, decided to fly through rather than over it. He stayed a little high to avoid a London bus crossing the bridge and was concerned that the upper walkway might remove his fin.

He burst clear, and now, fully committed to lawlessness, beat up Wattisham, Lakenheath and Marham then, as a finale, flew an inverted circuit at West Raynham.

After landing he was arrested and denied a court martial which threatened detrimental publicity. Instead, the RAF engineered a medical discharge.

There was much positive reaction to his flight, including a proposed motion of support from four MPs, later suppressed.

Pollock’s wasn’t the last of Tower Bridge’s aviation experiences. In 1970, an 18 year old who had earned his PPL via an RAF flying scholarship used a Cherokee from Biggin Hill to join the Bridge Threading Club. The next day he was emigrating and thought he had got away without being identified. When he came home 5 years later he was met by the CAA waving prosecution papers.

Then there was Paul Martin, a stockbroker’s clerk. He was out on bail following a fraud charge when, on 31st July 1973 he stole a Beagle Pup from the club at Blackbushe. He flew through the bridge twice then beat up several buildings in the City before heading off north. He reached Derwentwater in the Lake District where he crashed and was killed.

Then there was Paul Martin, a stockbroker’s clerk. He was out on bail following a fraud charge when, on 31st July 1973 he stole a Beagle Pup from the club at Blackbushe. He flew through the bridge twice then beat up several buildings in the City before heading off north. He reached Derwentwater in the Lake District where he crashed and was killed.

Next came a couple of helicopters in July 2004 who got permission to fly through the bridge with the bascules raised as part of a film, ‘Thunderbirds’.

And finally, for the time being anyway, there was another legal and rather sedate fly through of two helicopters, one filming the other, which was incorporated into Danny Boyle’s Olympic opening ceremony. https://youtu.be/VedDvH_PPT4

Having reviewed under-the-bridge aviation in London, it’s probably appropriate now to make this a tale of two cities and see what’s been going on in Paris.

In short, as far as this type of flying is concerned, absolutely nothing. The bridges over the Seine are so low that some barges have retracting wheelhouses so that they can squeeze through the constricted clearances. Even the buildings are of modest height. Tall structures in Paris are unusual, building height restrictions having been in place since the early 1600s.

In short, as far as this type of flying is concerned, absolutely nothing. The bridges over the Seine are so low that some barges have retracting wheelhouses so that they can squeeze through the constricted clearances. Even the buildings are of modest height. Tall structures in Paris are unusual, building height restrictions having been in place since the early 1600s.

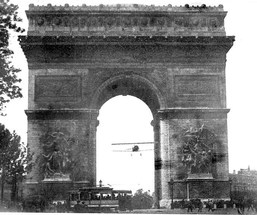

L’Arc de Triomphe is smaller but much more symbolic. It was the centrepiece of the post-war victory parade on 14th July 1919. Troops from every branch of the French armed forces and from every allied nation were to assemble and march through the Arch. But no fly-past was planned and this incensed a group of pilots. They met in a bar, of course, and soon produced a plan to fly a fighter plane through the Arch during the parade.

Jean Navarre, the ‘Guardian of Verdun’ was chosen and he practised assiduously near his airfield. He used a gap in convenient telephone wires but something went wrong just four days before the parade. He clipped one of the wires - some say he hit a hedge - and was killed.

Jean Navarre, the ‘Guardian of Verdun’ was chosen and he practised assiduously near his airfield. He used a gap in convenient telephone wires but something went wrong just four days before the parade. He clipped one of the wires - some say he hit a hedge - and was killed.

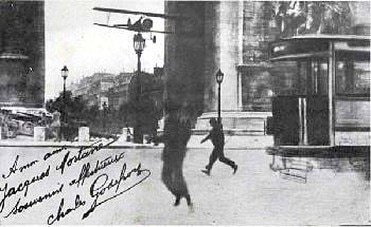

Volunteering to stand in, Charles Godefroy had to start his own practice and missed the parade. The opening in the arch is 29 metres high but only 14.5 metres wide. A Nieuport Bébé would have 3.5 m clearance from each wing-tip. Godefroy was ready on 7th August and flew to the centre of Paris. He circled the Arch twice then dived down, passing over a tram, some of whose passengers leapt out and crouched on the ground. Godefroy had asked a cine-camera owning friend to be there so we can still enjoy this historic event here –https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HIZzkq5Y8q0.

|

No one else could be first to fly through the Arc but inevitably, someone else would try. It was 62 years later, on 18th October 1881 when Alain Marchand, a former fighter pilot, did it in his Rallye as a protest against the government’s attitude towards light aviation. This has a span of 9.74 metres – that’s just 4.4m wing-tip clearance - and Marchand held the Rallye in a slight bank as he passed through. It cost him a 5,000 Fr. fine. |

Ten years later, in August 1991 a Mudry CAP 10 aerobatic two-seater (span 8.06m) did it again. It was 7.30 am and the CAP 10 had been stolen from an airfield east of Paris. The pilot first flew through the gap at the base of the Eiffel Tower before circling the Arc and finally lining up to fly through the arch. He abandoned the aeroplane in a field and was never identified.

Ten years later, in August 1991 a Mudry CAP 10 aerobatic two-seater (span 8.06m) did it again. It was 7.30 am and the CAP 10 had been stolen from an airfield east of Paris. The pilot first flew through the gap at the base of the Eiffel Tower before circling the Arc and finally lining up to fly through the arch. He abandoned the aeroplane in a field and was never identified.

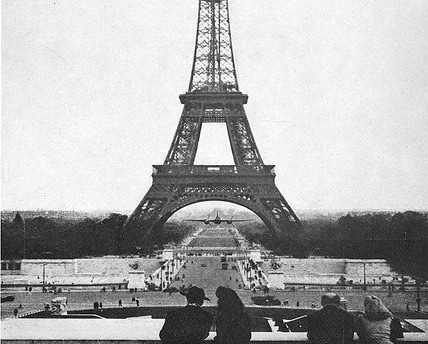

Much less challenging than the gap in the Arc de Triomphe, the Eiffel Tower’s arch is 74 metres wide at ground level and 39m high in the centre. Many pilots have flown safely, if not legally, through it. Not so Leon Collet. Here he is, in 1926, threading the gap, somewhat erratically, just before colliding with some cables. Collet died in the crash.

The most unusual and dramatic event took place in the spring of 1944.

Bill Overstreet was a 23-year old pilot of ‘Berlin Express’, a Mustang escorting bombers. He chased off a Messerschmitt 109 and damaged its engine. The German pilot flew low over Paris hoping to get support from the flak units based there. Unable to shake off the Mustang, the German flew under the arch of the Eiffel Tower, not expecting the Mustang to follow. Bill did, shooting down the 109 with another burst. He said ‘That’s a huge space. That’s not close at all. It’s plenty of room to go under the Eiffel Tower, but it makes a good story’. It was recorded in paint by Len Krenzler.

409 Sqn was the first RAF night fighter unit to be based in France. After the liberation of Paris, two 409 aircrew, WO Bob Boorman (RCAF) and his navigator, Flt. Sgt. Bill Bryant (RAF) were drinking in the Trocadero Hotel with two pressmen from ‘Stars and Stripes’, the US Forces newspaper. They said it would make a great photograph if the Mosquito flew through the lower arch.

The next day, 14th September, 1944, with sore heads but quite sober, they looked down on Paris and regretted the deal they had made. A couple of low level orbits convinced them that there was plenty of room so they zoomed through the arch at 250 mph, though they were surprised at how quickly they had to climb to avoid the Trocadero which sits on rising ground. The photograph was sent to the Squadron some weeks later and everyone maintained a diplomatic silence.

The final account in this saga concerns Robert Moriarty, an ex-US Marine fighter pilot. He was on his way home in his Bonanza and planned to fly from Paris to Shannon. It was 31st March 1984 when he took off and headed north until he was cleared by air traffic. Immediately, he came down to low level and sneaked back to Paris to fly under the Tower as a farewell gesture. His passenger had a video camera and you can enjoy the flight too. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_txdqnVP3-c. You’ll be travelling in the same direction as most pilots did, towards the Trocadero.

Afterwards, Moriarty thought that the French authorities were very reasonable. They said that as long as he stayed out of France for a few years, ‘no one would give him grief’.