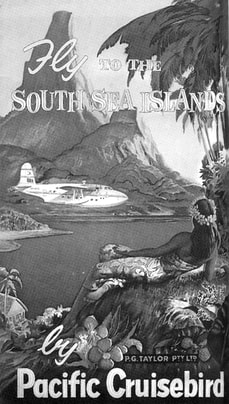

Navigator of the Southern Oceans (Jan 2022)

From his home in Australia his voyages spread across the map like the spokes of a wheel. Many were pioneering flights, some earned him awards and all were magnificent achievements which highlighted his proficiency as a skilled navigator in the days when aids were few or non-existent. On his later flights he was both Chief Pilot and Navigator.

1933 -Australia - New Zealand and return, with Charles Kingsford Smith

1933 - Australia – England – Australia, with Charles Ulm

1934 - Australia – Hawaii – USA, with Charles Kingsford Smith

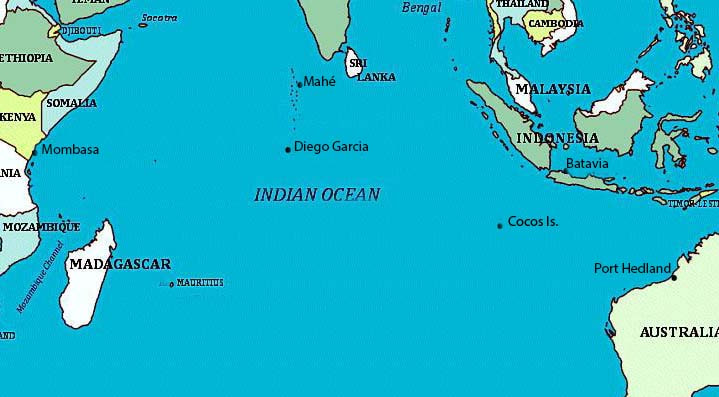

1935 - Australia – Indian Ocean – Kenya, with Richard Archbold

1945 - Bermuda – Mexico – New Zealand, Chief pilot and navigator

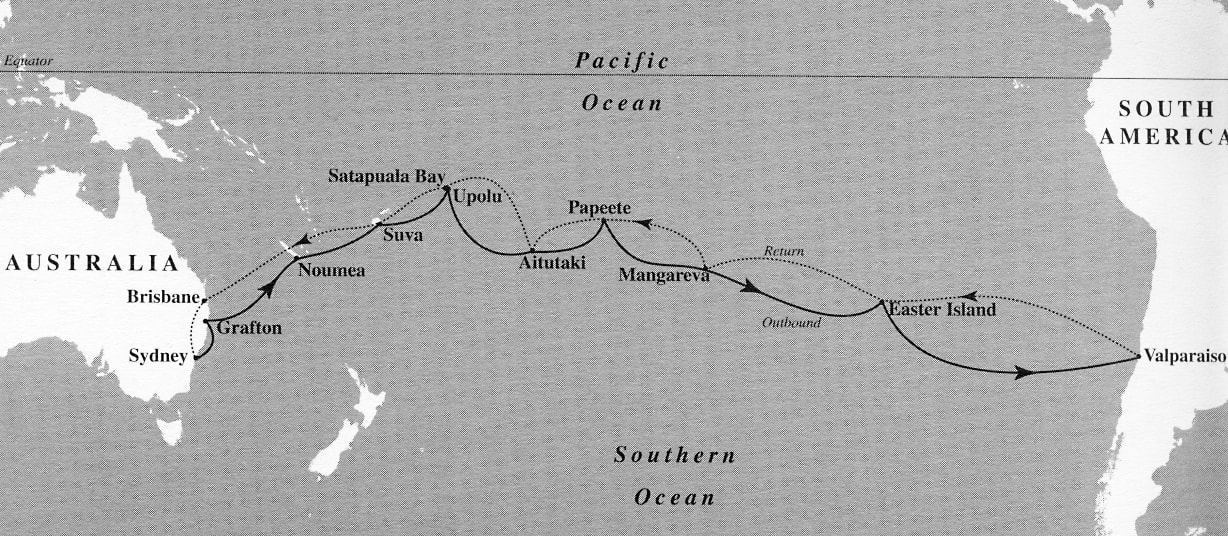

1951 - Australia – Chile – and return, Chief pilot and navigator

He was Sir Patrick Gordon Taylor, MC, GC.

1933 -Australia - New Zealand and return, with Charles Kingsford Smith

1933 - Australia – England – Australia, with Charles Ulm

1934 - Australia – Hawaii – USA, with Charles Kingsford Smith

1935 - Australia – Indian Ocean – Kenya, with Richard Archbold

1945 - Bermuda – Mexico – New Zealand, Chief pilot and navigator

1951 - Australia – Chile – and return, Chief pilot and navigator

He was Sir Patrick Gordon Taylor, MC, GC.

Born in 1896 in Sydney, he was the fourth child of a successful businessman. He didn’t like being named Patrick after his father and didn’t care much for Gordon either. He insisted he should be called Bill, which all his friends, but not his family, did. When his name is written in any record it is usually Gordon.

He didn’t enjoy school, apart from the sport and athletics. His exam results were no better than reasonable and he did not excel in mathematics. His father wanted him to study medicine, or join the family business. Neither appealed to Bill and his future was decided by events. In August 1914 war broke out in Europe and Bill enlisted in the Australian army.

He was stamping his way through basic training at a camp when he saw a report and pictures in a newspaper of an RNAS attack on Zeppelin sheds. That drew his attention to the activities at a nearby airfield and he determined that he would learn to fly. Because of his age, he needed his father’s permission to enlist in the RFC or RNAS and that was not easily given. In the end, his father conceded and Bill resigned from the army and sailed on the SS Anchises for England. It was late in 1916.

His father had given him a number of letters of introduction to various Australian officials and Army officers in London and these, plus, it seemed, the fact that he could ride a horse were sufficient to get Bill into the uniform of an RFC subaltern.

He didn’t enjoy school, apart from the sport and athletics. His exam results were no better than reasonable and he did not excel in mathematics. His father wanted him to study medicine, or join the family business. Neither appealed to Bill and his future was decided by events. In August 1914 war broke out in Europe and Bill enlisted in the Australian army.

He was stamping his way through basic training at a camp when he saw a report and pictures in a newspaper of an RNAS attack on Zeppelin sheds. That drew his attention to the activities at a nearby airfield and he determined that he would learn to fly. Because of his age, he needed his father’s permission to enlist in the RFC or RNAS and that was not easily given. In the end, his father conceded and Bill resigned from the army and sailed on the SS Anchises for England. It was late in 1916.

His father had given him a number of letters of introduction to various Australian officials and Army officers in London and these, plus, it seemed, the fact that he could ride a horse were sufficient to get Bill into the uniform of an RFC subaltern.

He had the all-too-common experience in training – being told to go solo after only three flights with a nerve-shattered ex-combat pilot, Capt. Collins. He refused and asked for a change of instructor. (He had made a friend, another Australian, and he too was ‘trained’ by Capt. Collins. He was killed in the crash which ended his first solo flight). Bill was lucky in that his new instructor trained him properly to a safe solo in a Maurice Farman.

A posting to Upavon introduced him to the BE.2c, Avro 504 and Sopwith 1½ Strutter. On his first cross country flight from Upavon he got lost and had to land to find out where he was. This embarrassed and irritated him so he made a point on future flights of constantly checking his position and direction of flight – navigating. In another flight he blundered into a cloud and managed to regain control when he fell out of it. In November 1917 he was proud to sew wings onto his uniform jacket.

Gunnery school followed and he was pleased to be posted to a unit for ‘advanced’ training flying the Sopwith Pup. His next posting was to the newly reformed 66 Squadron. The Flight commander, Capt Andrews, tested every pilot in mock combat. Bill was surprised to find that he had been appointed deputy leader and would lead his own section of three, following Andrews’ section. They trained hard, and Bill was determined to justify his position.

Gunnery school followed and he was pleased to be posted to a unit for ‘advanced’ training flying the Sopwith Pup. His next posting was to the newly reformed 66 Squadron. The Flight commander, Capt Andrews, tested every pilot in mock combat. Bill was surprised to find that he had been appointed deputy leader and would lead his own section of three, following Andrews’ section. They trained hard, and Bill was determined to justify his position.

Down below him was the Clifton Suspension Bridge. The gorge looked awfully narrow. Positioning the Pup carefully Bill pulled up into a stall turn and plunged down into the gorge. The wing tips swept past the walls, the bridge flashed over his head and he was through, climbing away and cruising gently back to his airfield.

A few days later they were in France.

66 Squadron was based at Vert Galant Farm, north of Amiens and some 15 miles from the front line. They flew practice patrols to familiarise themselves with the countryside. Bill prepared a number of strip maps which he stuck onto plywood to prevent them blowing out of the cockpit. They practised gunnery, firing at a target on the ground. It was here that they had their first casualty. One of the pilots was overcome by target fixation and pulled out of his dive too late and too violently. The wings of the Pup broke off and the fuselage speared the ground, killing the pilot.

They practised dealing with their opponents. The Germans had recently introduced the Albatros D II with a powerful 185 hp engine. It was much faster than the Pup and had greater fire power, with twin 8mm machine guns. The lighter Pup had a 80 hp engine. It was more manoeuvrable and climbed faster than the Albatros. They planned to do their fighting at high altitude.

They settled into a routine of daily, often twice daily patrols, climbing to 14,000 ft, crossing the line and cruising north and south over their sector. Skirmishes with Albatri and attacks on two seaters were mostly inconclusive. All the time they were beset by problems with unreliable engines and breaking equipment. Every patrol ended with a list of jobs for the hard working mechanics, replacement or repair of something broken or damaged as well, of course, damage caused by enemy guns. Bill escaped from one fight by diving to ground level whilst the chasing Albatros poured bullets into his tail. After he landed everyone was amazed at how much damage had been caused to the Pup. Even the cables to the tail controls had been cut and were trailing behind on the grass. But Bill had still be able to control the Pup because, just a few days earlier, his mechanic had thought that the single cables were not robust enough and had fitted a duplicate set.

The squadron was ordered to move to a new airfield at Estrée Blanche, 40 miles north. The CO was on leave so Bill was in charge. A couple of days before the move he flew to Estrée Blanche, noting rivers, railways and other landmarks on the way. The route was well behind the lines so there should be no enemy interference. The only problem could be with the weather. Sure enough, on the day of the move, the cloud base was low and visibility poor. Mindful of his experiences in training, he briefed the pilots that they should not under any circumstances climb into cloud. If lost, they should land in a field and wait for the weather to clear. They had to go, because the squadron’s ground party had already left. In the event, despite the weather, all went well and when they reached Estrée Blanche they were greeted by the mechanics who had gone on ahead.

The squadron had been moved to support an offensive which became known as the Battle of Messines (which began with the detonation of nineteen huge mines). The fighting was intensive and Bill’s logbook is peppered with notes of aircraft ‘diving away in flames’, or ‘shedding pieces’. He never followed them to check on the crash, nor did he make any claims to ‘build up a score’. But his successes must have been noted in the squadron’s records for Bill was awarded the Military Cross ‘for showing exceptional dash and gallantry’. When Andrews left to go to England Bill was promoted to Captain and given command of the flight.

The squadron was ordered to move to a new airfield at Estrée Blanche, 40 miles north. The CO was on leave so Bill was in charge. A couple of days before the move he flew to Estrée Blanche, noting rivers, railways and other landmarks on the way. The route was well behind the lines so there should be no enemy interference. The only problem could be with the weather. Sure enough, on the day of the move, the cloud base was low and visibility poor. Mindful of his experiences in training, he briefed the pilots that they should not under any circumstances climb into cloud. If lost, they should land in a field and wait for the weather to clear. They had to go, because the squadron’s ground party had already left. In the event, despite the weather, all went well and when they reached Estrée Blanche they were greeted by the mechanics who had gone on ahead.

The squadron had been moved to support an offensive which became known as the Battle of Messines (which began with the detonation of nineteen huge mines). The fighting was intensive and Bill’s logbook is peppered with notes of aircraft ‘diving away in flames’, or ‘shedding pieces’. He never followed them to check on the crash, nor did he make any claims to ‘build up a score’. But his successes must have been noted in the squadron’s records for Bill was awarded the Military Cross ‘for showing exceptional dash and gallantry’. When Andrews left to go to England Bill was promoted to Captain and given command of the flight.

His reluctance to make claims for ‘victories’ was one indication of his attitude to the war. It was brought into dramatic focus by what happened when he last shot down one of the enemy. The Pups attacked a flight of Rumplers. Bill got close underneath one and began firing into its belly until the Pup stalled and fell away. The Rumpler flew on, apparently undamaged and Bill chased after it. Then he saw a little glow of flame and a thin trail of black smoke. The thickening of the smoke matched the rising glow of triumph Bill felt at shooting down a hated Hun.

Then something fell from the Rumpler. It was the gunner. He seemed to fall slowly and passed close to the Pup. Bill looked into his face and was overwhelmed with utter horror. He’d seen many planes shot down and crash but it had all been so impersonal. Destroying a weapon of war was a worthy thing to do. Now Bill felt that he had caused another human being deliberately to end his life. He wanted to get as far from the war as possible.

Fortunately, he was not tested in another action. After 77 offensive patrols it was time for a home posting and in September 1918 he returned to England to train new pilots on the SE 5a. In October, he went home to Australia for a brief spell at the Central Flying School, finally being discharged in March 1919.

________________________________________________________________

He was determined to make a career in civil aviation and an opportunity presented itself almost at once. The Aerial Company of Sydney had bought two war surplus DH 6s and needed pilots to fly them from Melbourne to Sydney. Bill immediately had a job.

Fortunately, he was not tested in another action. After 77 offensive patrols it was time for a home posting and in September 1918 he returned to England to train new pilots on the SE 5a. In October, he went home to Australia for a brief spell at the Central Flying School, finally being discharged in March 1919.

________________________________________________________________

He was determined to make a career in civil aviation and an opportunity presented itself almost at once. The Aerial Company of Sydney had bought two war surplus DH 6s and needed pilots to fly them from Melbourne to Sydney. Bill immediately had a job.

The Airco DH 6 had been designed by Geoffrey De Havilland as a trainer, easy to build and repair and safe to fly. It was an uninspiring machine and acquired a variety of nicknames, ‘crab’, ‘clockwork mouse’ and most popular ‘clutching hand’. Despite its 90 hp RAF 1a engine, its cruising speed was little more than 60 mph. The direct 400+ mile course to Sydney crossed a range of mountains, some rising to over 6000 ft. Bill and his fellow delivery pilot elected to follow a longer curving route over country where there were larger fields and help wherever they chose to land.

They were wise to do so. After several forced landings with engine problems Bill reached Sydney ten days later. He was greeted by a large crowd in a unexpected blaze of publicity. Such long cross-country flights were rare and the Aerial Company had promoted the reception. (The other machine suffered a series of breakdowns and gave up the flight. Its Aerial Company passenger finished the journey by train).

Bill’s next job was to ferry a politician round New South Wales on a two week electioneering tour. After that, apart from a few sight-seeing flights around Sydney, there were few further opportunities to fly.

On 29 December 1924, Bill got married. Yolande Bede Dalley, whom Bill called ‘Twee’, came from one of Australia’s eminent families. They had many shared interests and seemed entirely suited. But after a few months, they parted and Bill moved out for some reason which has never been discovered. Yet, they remained friends and Bill supported Twee financially, with advice and other ways of help until 1938 when they were finally divorced.

Bill’s family encouraged him to get involved in the family businesses. He was a shareholder and could have had a seat on the board but he had little interest in it and felt he could make no worthwhile contribution. He became involved with the Australian Aircraft and Engineering Company where he carried out a number of projects which required him to undertake theoretical studies of engineering subjects. During several visits to England he did similar unpaid work with the De Havilland Company.

Whilst in England, he topped up his wardrobe with suits from Savile Row and bought a prestigious English or Italian car which he shipped home. He maintained his cars himself and kept comprehensive records detailing every job done and every penny spent. This ensured he got a good price when he sold them before his next trip to Europe.

About this time, there was a number of long range flights which attracted Bill Taylor’s attention. He was particularly interested in how they navigated. The Smith brothers had flown their Vimy from England to Australia, largely by map-reading. The early trans-Atlantic fliers had maps which had were useless over the sea. It seemed they could not or did not try to plot their position. If they had done it would only have been by using mariners’ methods of navigation. Every flight from Australia involved an ocean crossing and if he wanted to be a ‘complete’ aviator he had to learn to use those mariners’ methods.

He enlisted the help of a man who had been Director of Studies at the Royal Australian Naval College. Although maths had been one of Bill’s weaker subjects at schools the interest he had in being able to work out his position by astro-navigation brought out an unexpected facility in understanding the complex formulae and calculations, even spherical trigonometry. He was introduced to the skipper of a ship based in Sydney harbour who, on a clear December night took him out onto the deck. There, without the confusion of cluttered constellation charts he was taught to identify the important stars he would need to use for navigation.

This study was spread over several months, interspersed with his other activities. Bill reached the stage when he wanted to put his new skill into practice. Ship’s instruments weren’t suitable for use in an aircraft so he sought the help of an instrument engineer. Together they designed a drift sight that could be used with a floating flare or a patch of dye to calculate the angle of drift compared with the heading of the aircraft. Then, he turned to the sextant which is used to measure angles in relation to the horizon. The horizon is invisible to anyone flying higher than cloud base or at night so Bill designed a sextant with its own horizon - a spirit level.

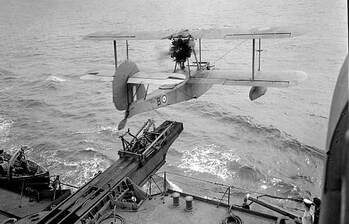

Now, all he needed to practise his navigational skills and instruments was an aeroplane. He could have hired one but he had been impressed with De Havilland’s Moth which he had flown on his last visit to England in 1926. He ordered one, asking it to have a 100 hp Gipsy engine rather than the standard 60 hp Cirrus. He needed the extra power because he wanted it to be fitted with floats. It was delivered to him with wheels and he bought a pair of surplus RAAF float that had been made by Shorts.

Bill’s next job was to ferry a politician round New South Wales on a two week electioneering tour. After that, apart from a few sight-seeing flights around Sydney, there were few further opportunities to fly.

On 29 December 1924, Bill got married. Yolande Bede Dalley, whom Bill called ‘Twee’, came from one of Australia’s eminent families. They had many shared interests and seemed entirely suited. But after a few months, they parted and Bill moved out for some reason which has never been discovered. Yet, they remained friends and Bill supported Twee financially, with advice and other ways of help until 1938 when they were finally divorced.

Bill’s family encouraged him to get involved in the family businesses. He was a shareholder and could have had a seat on the board but he had little interest in it and felt he could make no worthwhile contribution. He became involved with the Australian Aircraft and Engineering Company where he carried out a number of projects which required him to undertake theoretical studies of engineering subjects. During several visits to England he did similar unpaid work with the De Havilland Company.

Whilst in England, he topped up his wardrobe with suits from Savile Row and bought a prestigious English or Italian car which he shipped home. He maintained his cars himself and kept comprehensive records detailing every job done and every penny spent. This ensured he got a good price when he sold them before his next trip to Europe.

About this time, there was a number of long range flights which attracted Bill Taylor’s attention. He was particularly interested in how they navigated. The Smith brothers had flown their Vimy from England to Australia, largely by map-reading. The early trans-Atlantic fliers had maps which had were useless over the sea. It seemed they could not or did not try to plot their position. If they had done it would only have been by using mariners’ methods of navigation. Every flight from Australia involved an ocean crossing and if he wanted to be a ‘complete’ aviator he had to learn to use those mariners’ methods.

He enlisted the help of a man who had been Director of Studies at the Royal Australian Naval College. Although maths had been one of Bill’s weaker subjects at schools the interest he had in being able to work out his position by astro-navigation brought out an unexpected facility in understanding the complex formulae and calculations, even spherical trigonometry. He was introduced to the skipper of a ship based in Sydney harbour who, on a clear December night took him out onto the deck. There, without the confusion of cluttered constellation charts he was taught to identify the important stars he would need to use for navigation.

This study was spread over several months, interspersed with his other activities. Bill reached the stage when he wanted to put his new skill into practice. Ship’s instruments weren’t suitable for use in an aircraft so he sought the help of an instrument engineer. Together they designed a drift sight that could be used with a floating flare or a patch of dye to calculate the angle of drift compared with the heading of the aircraft. Then, he turned to the sextant which is used to measure angles in relation to the horizon. The horizon is invisible to anyone flying higher than cloud base or at night so Bill designed a sextant with its own horizon - a spirit level.

Now, all he needed to practise his navigational skills and instruments was an aeroplane. He could have hired one but he had been impressed with De Havilland’s Moth which he had flown on his last visit to England in 1926. He ordered one, asking it to have a 100 hp Gipsy engine rather than the standard 60 hp Cirrus. He needed the extra power because he wanted it to be fitted with floats. It was delivered to him with wheels and he bought a pair of surplus RAAF float that had been made by Shorts.

He had learned enough in his work with the Australian company and De Havilland to design the fittings and do the weight and balance calculations. On the concrete slipway that he had built at his house by the sea he united the Moth and the floats. The work was inspected and approved for certification.

A floated Gipsy Moth (Not Bill’s. That was VH-UIH)

He had never flown a seaplane before so everything was a new experience. Just starting the engine was very different. He had to swing the propeller himself, standing on the float behind it. As soon as the engine burst into life, the Moth started to move. Bill had to scramble back over the wing and into the cockpit to take control. He had the great advantage of having sailed these waters since he was a boy and knew the flow of the tides and the way the wind was affected by the hills and the land around the bay. He learned how to control the drift when taxying cross wind and how to keep the wing tips clear of the water whilst turning. He was gratified to find that fast taxying, a take off and a ‘landing’ all confirmed that he had fitted the floats at the correct angle. He found the whole experience challenging and exhilarating.

A greater challenge awaited him when he took his sextant into the air. He found it impossible to use it when he was flying solo and even with another pilot holding the aeroplane steady he couldn’t get the bubble and the sun to coincide for more than a second. He had to redesign the sextant. He made a new bubble chamber which effectively restricted the movement of the bubble. It worked so well that he was able to take a sun shot whilst holding the Moth steady with his knees.

He made another ‘instrument’. He knew he would be flying at night and when alighting it would be impossible to judge his height above the water if there were no lights to reflect off it. He fitted a spring loaded rod fore and aft to a pivot between the floats and normally latched to a hook under the tail. When needed, the rod would be released and pivot down so that it hung vertically below the Moth as it approached. When the rod touched the water it would swing back and a dial in the cockpit showed its angle. Bill would know when the floats were about to touch the water. He felt he was now completely equipped with a aircraft, admittedly a minimal seaplane, and more importantly, with the navigational instruments and skills for a flight, day or night, over the seas.

He offered charter, sight seeing and photographic flights in his Moth, operating from harbours and seaside towns where the tourists were. He organised a couple of holidays for himself. With his tent and fishing gear he flew south to Hobart in Tasmania. A second trip was the basis of an account ‘A Seaplane Cruise to North Queensland’ which was published in Flying magazine, the first words of Bill’s to appear in print.

__________________________________________

A greater challenge awaited him when he took his sextant into the air. He found it impossible to use it when he was flying solo and even with another pilot holding the aeroplane steady he couldn’t get the bubble and the sun to coincide for more than a second. He had to redesign the sextant. He made a new bubble chamber which effectively restricted the movement of the bubble. It worked so well that he was able to take a sun shot whilst holding the Moth steady with his knees.

He made another ‘instrument’. He knew he would be flying at night and when alighting it would be impossible to judge his height above the water if there were no lights to reflect off it. He fitted a spring loaded rod fore and aft to a pivot between the floats and normally latched to a hook under the tail. When needed, the rod would be released and pivot down so that it hung vertically below the Moth as it approached. When the rod touched the water it would swing back and a dial in the cockpit showed its angle. Bill would know when the floats were about to touch the water. He felt he was now completely equipped with a aircraft, admittedly a minimal seaplane, and more importantly, with the navigational instruments and skills for a flight, day or night, over the seas.

He offered charter, sight seeing and photographic flights in his Moth, operating from harbours and seaside towns where the tourists were. He organised a couple of holidays for himself. With his tent and fishing gear he flew south to Hobart in Tasmania. A second trip was the basis of an account ‘A Seaplane Cruise to North Queensland’ which was published in Flying magazine, the first words of Bill’s to appear in print.

__________________________________________

Airline Pilot

In 1928 Charles Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm had made the first flight across the Pacific from the USA to Australia in a Fokker Trimotor Southern Cross. In the aftermath, they had formed an airline, Australian National Airlines, flying mail and passengers from Sydney to Brisbane and Melbourne. They used Avro 10s, licence-built versions of the Fokker Trimotor. (Strictly, this was the Avro 618. It was called the 10 because it carries ten people - 2 crew and 8 passengers).

Bill had seen these aeroplanes flying from Sydney and thought that being captain of an airliner would be a worthwhile job. Early in 1930, he applied to ANA for a job as a pilot. He had a brusque interview with Ulm who offered to take him as a second pilot, on probation. This was not what Bill had hoped for but he agreed to take it.

His first flight was to be from Sydney to Melbourne and he waited at the door of the Avro for the pilot to appear. At the last minute, he turned up, grunted a ‘hello’ and climbed aboard, ignoring the passengers. It was a young Scot, called Jimmy Mollison. Bill followed and they settled into the pilots’ seats. Mollison said nothing, started the engines and they took off, climbing slowly to 8000ft. This was the reverse of the route which Bill had followed all those years ago in the old DH 6. The direct course was over the mountains which were now covered by the building cloud. But Mollison didn’t change course. Soon they were flying in and out of the turbulent clouds. The Avros had no artificial horizon, just a basic turn and slip indicator.

Mollison skilfully maintained control with this limited instrument, made no comment to Bill and ignored the airsick passengers. Bill became increasingly concerned. For nearly five hours they had not been able to check their position and now Mollison casually closed the throttles and they began to descend. At 3000 ft a few patches of ground appeared and when they were clear of cloud they were perfectly positioned to approach Essendon Airport. Bill began to think that Ulm’s reluctance to employ him was justified. Maybe he wasn’t the right man to be an airliner captain.

He managed a conversation with Mollison before the return flight next day. Mollinson had seen a brief gap in the clouds an his side of the Avro and had recognised a landmark which he knew well allowing him to calculate exactly when to close the throttles. Bill’s flights with other ANA pilots reassured him that he was quite capable of living up to ANA’s slogan that they employed the ‘World’s Best and Safest Pilots’ and also that a press-on attitude like Mollison’s was not an essential requirement.

Within three months, he had been promoted to Captain. He took his responsibilities seriously and began making suggestions to improve efficiency or safety. One thing he couldn’t change was the 8.00 am starting time for the flights. The latest information the pilots had on the weather was from the morning newspaper which published the forecast for the day which had been prepared by the Bureau of Meteorology the night before. When the day’s forecast did emerge at 9.00 am all the pilots were well on their way and without radio, there was no way to update them. Unexpected bad weather caused many delays and diversions and worse, eventually contributed to the airline’s demise.

In March 1931 one of the Avros, Southern Cloud, ran into bad weather on the Melbourne run and disappeared. Every available aeroplane was used in the search for survivors. No wreckage was found and the search was eventually called off. The cost of the search and the loss of confidence of the customers was too much to bear and the company had to be wound up. (It wasn’t until 1958 that the wreckage was found in the Snowy Mountains midway between Sydney and Melbourne).

___________________________________________

Flying the Southern Cross

Bill Taylor was once again out of a job. However, in the last weeks of his time with ANA he had been asked to take an Avro up ‘for a test flight’. Unusually, he was to be accompanied by Kingsford Smith who didn’t normally fly with the airline. After they landed Smithy told Bill that he would now be allowed to fly the famous Southern Cross which was kept serviceable and used for special occasions. Smithy and Ulm (who had flown the Pacific together) were very different characters and were no longer working as a team. Smithy was planning a promotional tour of New Zealand with the Cross to raise funds. He needed a second pilot and a navigator and Bill was the man he chose. It was to be the beginning of a special partnership.

His first flight was to be from Sydney to Melbourne and he waited at the door of the Avro for the pilot to appear. At the last minute, he turned up, grunted a ‘hello’ and climbed aboard, ignoring the passengers. It was a young Scot, called Jimmy Mollison. Bill followed and they settled into the pilots’ seats. Mollison said nothing, started the engines and they took off, climbing slowly to 8000ft. This was the reverse of the route which Bill had followed all those years ago in the old DH 6. The direct course was over the mountains which were now covered by the building cloud. But Mollison didn’t change course. Soon they were flying in and out of the turbulent clouds. The Avros had no artificial horizon, just a basic turn and slip indicator.

Mollison skilfully maintained control with this limited instrument, made no comment to Bill and ignored the airsick passengers. Bill became increasingly concerned. For nearly five hours they had not been able to check their position and now Mollison casually closed the throttles and they began to descend. At 3000 ft a few patches of ground appeared and when they were clear of cloud they were perfectly positioned to approach Essendon Airport. Bill began to think that Ulm’s reluctance to employ him was justified. Maybe he wasn’t the right man to be an airliner captain.

He managed a conversation with Mollison before the return flight next day. Mollinson had seen a brief gap in the clouds an his side of the Avro and had recognised a landmark which he knew well allowing him to calculate exactly when to close the throttles. Bill’s flights with other ANA pilots reassured him that he was quite capable of living up to ANA’s slogan that they employed the ‘World’s Best and Safest Pilots’ and also that a press-on attitude like Mollison’s was not an essential requirement.

Within three months, he had been promoted to Captain. He took his responsibilities seriously and began making suggestions to improve efficiency or safety. One thing he couldn’t change was the 8.00 am starting time for the flights. The latest information the pilots had on the weather was from the morning newspaper which published the forecast for the day which had been prepared by the Bureau of Meteorology the night before. When the day’s forecast did emerge at 9.00 am all the pilots were well on their way and without radio, there was no way to update them. Unexpected bad weather caused many delays and diversions and worse, eventually contributed to the airline’s demise.

In March 1931 one of the Avros, Southern Cloud, ran into bad weather on the Melbourne run and disappeared. Every available aeroplane was used in the search for survivors. No wreckage was found and the search was eventually called off. The cost of the search and the loss of confidence of the customers was too much to bear and the company had to be wound up. (It wasn’t until 1958 that the wreckage was found in the Snowy Mountains midway between Sydney and Melbourne).

___________________________________________

Flying the Southern Cross

Bill Taylor was once again out of a job. However, in the last weeks of his time with ANA he had been asked to take an Avro up ‘for a test flight’. Unusually, he was to be accompanied by Kingsford Smith who didn’t normally fly with the airline. After they landed Smithy told Bill that he would now be allowed to fly the famous Southern Cross which was kept serviceable and used for special occasions. Smithy and Ulm (who had flown the Pacific together) were very different characters and were no longer working as a team. Smithy was planning a promotional tour of New Zealand with the Cross to raise funds. He needed a second pilot and a navigator and Bill was the man he chose. It was to be the beginning of a special partnership.

Bill prepared all his navigational equipment, charts, books of tables, his drift sight and bubble compass. The Cross was loaded with extra fuel and would need a longer take off run than was available at Sydney airport so was taken to Seven Mile Beach. Although take off was to be at 3.00 am (on 15 January 1933) there was a sizeable crowd to see them off.

Their destination was New Plymouth on New Zealand’s North Island, 1660 miles away.

Their destination was New Plymouth on New Zealand’s North Island, 1660 miles away.

Bill had worked out a course to steer based on the estimated wind. He had arranged for a fire to be lit at the departure point and when it was on the horizon behind them he took a bearing. He was surprised to find that the drift was as much as 12° to starboard. It was an overcast night with no star visible and they had no flare to drop on the sea to check the drift again. After a while he relieved Smithy who went back into the cabin where he and John Stannage, the radio operator, caught up with their sleep. Alone at the controls Bill followed the course he had worked out. Had he calculated correctly? New Zealand was a large target but on this heading they could miss it entirely and plough on into the wide Pacific.

Smithy was flying again when the eastern horizon lightened. Below them the waves were being whipped into foam by gale force winds. Bill’s drift sight showed that the drift to starboard was now an astonishing 30°. He needed a position line and had to wait until the sun came abeam. With a steady hand on his sextant he carefully took the shot and turned to his chart and tables. The position he worked out showed them to be more than 60 miles south of track. To make landfall at New Plymouth the change of course needed seemed too large to be credible. Bill kept his doubts to himself and halved it. At least they would reach New Zealand.

Of course, they did and when Bill checked his calculations he found no error. His instruments had all worked correctly and he had plotted exactly the course they had flown.

Smithy was flying again when the eastern horizon lightened. Below them the waves were being whipped into foam by gale force winds. Bill’s drift sight showed that the drift to starboard was now an astonishing 30°. He needed a position line and had to wait until the sun came abeam. With a steady hand on his sextant he carefully took the shot and turned to his chart and tables. The position he worked out showed them to be more than 60 miles south of track. To make landfall at New Plymouth the change of course needed seemed too large to be credible. Bill kept his doubts to himself and halved it. At least they would reach New Zealand.

Of course, they did and when Bill checked his calculations he found no error. His instruments had all worked correctly and he had plotted exactly the course they had flown.

They got a tremendous welcome at New Plymouth. Smithy embarked on a extended tour of the country, giving talks and some flights and raising lots of money for his next project. Bill and John Stannage went home by sea.

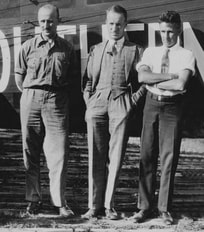

Gordon(Bill)Taylor, Charles Kingsford Smith

and John Stannage at New Plymouth NZ

Two months later they returned to fly the Southern Cross back to Australia. This time the flight was uncomplicated by weather and Bill’s navigation was precise and confident.

_____________________________________

To England and Beyond

Gordon Taylor’s last regular employment had been with Australia National Airlines flying passengers from Sydney to Melbourne and Brisbane. It went out of business at the end of 1931 and with it died the dream of Kingsford Smith and Ulm to operate an airmail service to England.

(Imperial Airways had a mail service between England and Calcutta. In April 1931 they sent one aeroplane on towards Australia. This crashed in Timor and Kingsford Smith flew the Southern Cross to collect the mail. He was hired by Imperial a second time to collect the mail from Burma. ANA (i.e. Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm) decided to do the job properly and organised a Christmas Airmail flight all the way to England. The Avro 10 Southern Sun, loaded with 52,000 letters and packages set off from Sydney in November 1931. Unfortunately its journey ended in a bog in Malaya. Smithy took Southern Star to rescue the mail and take it to England. He returned to Australia with a full load of mail. When the Australian government announced that they would charter an airmail service to England it was too late for ANA. They were no longer a registered company and the business went to Imperial and Qantas).

Charles Ulm didn’t give up. He reasoned that if he did something spectacular it would build on the fame and reputation of his trans-Pacific flight and show that he was a serious contender to operate an airmail service. He would fly right around the world – and be the first person to do so – by flying via England to California and then across the Pacific, back to Australia. Other people liked his plan. He was able to raise sufficient money from sponsors to buy Southern Moon, another ex-ANA Avro 10, from the receivers. He had it extensively modified, strengthened the fuselage, added wingspan and fitted new Whirlwind engines, new propellers and ten aluminium tanks to extend the range. He hired Scotty Allan (ex-ANA) as pilot and radio operator, Bill Taylor as second pilot and navigator and he, Ulm, would fly as Commander and relief pilot. There was one small caveat. No-one would be paid, nor have their expenses reimbursed, until the flight reached ‘a successful conclusion’.

Ulm got busy organising fuel supplies and permissions to land at their planned stops along the route. Allan was a competent pilot and engineer but knew nothing about radio. He devised a self training course with much advice from other operators. Bill Taylor compiled charts and collected information about all the airfields they might use. The heavily laden Avro would need long runways for a safe take off. He was particularly concerned about the small airfield in Fiji. There were no alternatives in that area of the Pacific and Smithy had had problems there with Southern Cross on his trans-Pacific flight.

Bill Taylor took a ship to Fiji. He was warmly welcomed and the islanders willingly agreed to do the work necessary to clear obstructions on the approaches to the runway and to firm up any soft ground. This was Bill’s first visit to a Pacific island and he was much impressed by the beautiful surroundings and the friendliness of the inhabitants. It was to sow a seed which was to flower years later and become a significant part of his life.

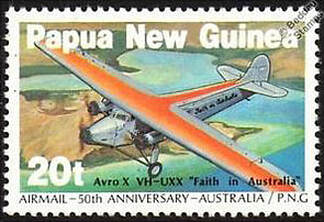

The old Avro emerged from the hangar looking like new and with a new name - Faith in Australia. Painted overall silver, its upper surfaces were orange, intended to help searchers if they force landed in an unpopulated area. The commemorative stamp produced 50 years later reveals this.

Gordon Taylor’s last regular employment had been with Australia National Airlines flying passengers from Sydney to Melbourne and Brisbane. It went out of business at the end of 1931 and with it died the dream of Kingsford Smith and Ulm to operate an airmail service to England.

(Imperial Airways had a mail service between England and Calcutta. In April 1931 they sent one aeroplane on towards Australia. This crashed in Timor and Kingsford Smith flew the Southern Cross to collect the mail. He was hired by Imperial a second time to collect the mail from Burma. ANA (i.e. Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm) decided to do the job properly and organised a Christmas Airmail flight all the way to England. The Avro 10 Southern Sun, loaded with 52,000 letters and packages set off from Sydney in November 1931. Unfortunately its journey ended in a bog in Malaya. Smithy took Southern Star to rescue the mail and take it to England. He returned to Australia with a full load of mail. When the Australian government announced that they would charter an airmail service to England it was too late for ANA. They were no longer a registered company and the business went to Imperial and Qantas).

Charles Ulm didn’t give up. He reasoned that if he did something spectacular it would build on the fame and reputation of his trans-Pacific flight and show that he was a serious contender to operate an airmail service. He would fly right around the world – and be the first person to do so – by flying via England to California and then across the Pacific, back to Australia. Other people liked his plan. He was able to raise sufficient money from sponsors to buy Southern Moon, another ex-ANA Avro 10, from the receivers. He had it extensively modified, strengthened the fuselage, added wingspan and fitted new Whirlwind engines, new propellers and ten aluminium tanks to extend the range. He hired Scotty Allan (ex-ANA) as pilot and radio operator, Bill Taylor as second pilot and navigator and he, Ulm, would fly as Commander and relief pilot. There was one small caveat. No-one would be paid, nor have their expenses reimbursed, until the flight reached ‘a successful conclusion’.

Ulm got busy organising fuel supplies and permissions to land at their planned stops along the route. Allan was a competent pilot and engineer but knew nothing about radio. He devised a self training course with much advice from other operators. Bill Taylor compiled charts and collected information about all the airfields they might use. The heavily laden Avro would need long runways for a safe take off. He was particularly concerned about the small airfield in Fiji. There were no alternatives in that area of the Pacific and Smithy had had problems there with Southern Cross on his trans-Pacific flight.

Bill Taylor took a ship to Fiji. He was warmly welcomed and the islanders willingly agreed to do the work necessary to clear obstructions on the approaches to the runway and to firm up any soft ground. This was Bill’s first visit to a Pacific island and he was much impressed by the beautiful surroundings and the friendliness of the inhabitants. It was to sow a seed which was to flower years later and become a significant part of his life.

The old Avro emerged from the hangar looking like new and with a new name - Faith in Australia. Painted overall silver, its upper surfaces were orange, intended to help searchers if they force landed in an unpopulated area. The commemorative stamp produced 50 years later reveals this.

Immediately, they hit a problem. The engines wouldn’t start. To save weight, the hand operated inertia starters had been removed. If the engines were turned to the top of the compression stroke and the ignition retarded an impulse from the magneto would make them fire. The engines thought otherwise. Allan climbed on a platform and swung the props. That meant they needed to take a platform with them on the flight. A platform that was not too heavy and which could be folded to get it through the doorway. They came to hate standing on the spindly marginally stable construction with the prop spinning inches from their faces but it worked and never caused any sudden alarm.

A number of test flights were made to establish how much runway would be needed for a safe take off. The maximum load of a standard Avro 10 was 10,000 lbs: the much modified Faith, fully fuelled, weighed 16,750 lbs. They went to ‘the largest paddock in New South Wales’ where the willing farmer knocked down a few fences and firmed up some patches of ground.

On the morning of 21 June, 1932 Scotty Allan opened the throttles to take off on the first leg of their epic round-the-world flight. After a run of 3,500 yards Faith left the ground. Their destination was the small town of Derby, on the coast of north western Australia. They flew steadily on all day across the desert of central Australia and into the night. Bill was at the controls when all three engines back fired – and stopped. It could only mean lack of fuel. The engines were fed from gravity tanks in the wings and they had run dry. Ulm rushed to the hand operated pump by the tanks in the cabin. Bill prepared for a forced landing in the dark. They ware saved from what would inevitably been a crash landing when, one by one, the engines coughed back to life.

Petrol fumes filled the cabin and they realised that there was a leak in the fuel lines. They had to pump continuously, taking 20 minute shifts, which was as long as they could stand in the noxious fumes. It was full daylight before Derby came into view. They landed and breathed clean air. It was just the first of the many problems they would suffer from in the course of their flight.

The leaking pump was replaced by an old, heavy but efficient rotary pump that had been used on a well and they set off on the next leg, an 1800 mile 16½ hour trouble free flight to Singapore. The journey to Rangoon was interrupted by a loose and vibrating cylinder on the starboard engine. They had to divert to an airfield in Malaya to fix it. At Rangoon, after a night of heavy rain, they were taxying out for take off and they ran into a patch of soft ground. The wheels sank in to the axle and Faith tipped forwards to almost 45º.

Luckily, the spinning propeller of the central engine stayed clear of the ground. The heavily loaded aeroplane crashed back, the tailskid drilled into the ground and Faith was sitting on its fuselage. Hours later, they were finally dug out and dragged to the end of the runway. They could no see no sign of any damage to the aeroplane so they left for the relatively short flight to Calcutta.

One of the aims of the flight had been to break the record for the Australia – England flight. The dismal progress so far was ruled this out. However they could make an impact on the Calcutta – London record with three long legs, stopping only in Karachi and Cairo.

Calcutta to Karachi went well. Over Persia, they flew into a tremendous dust storm. They tried to climb over it but the engines overheated. Allan reduced the throttles and Faith lost height. The port engine banged and misfired so Allan shut it down. They dumped fuel and headed for the nearest airfield. With the starboard engine showing signs of distress they landed at Jask. Ulm had not applied for permission to land in Persia so they were faced with a bureaucratic problem.

Using the spares he had brought, Allan replaced the piston in the port engine which had disintegrated. Several worn piston rings needed replacement. Four days later, Ulm was given permission for a ‘test flight’. They had enough fuel for the test flight to end in Basra in Iraq. They pressed on in short stages, nursing the engines until, over France, the starboard engine stopped and they landed at Orange, a military airfield. They gave up. Ulm cabled England and a Wright engine specialist arrived to rebuild the engines. He also fitted inertia starters and the hated platform was abandoned. They finally reached Heston on 9th July, 19 days since leaving Australia.

To their surprise they were warmly welcomed and given generous help in overhauling Faith and its troublesome engines. Bill was able to get a brand new RAF Mk VIII bubble sextant, much easier to operate than his own hand made prototype. He also had the compasses swung again.

The trans-Atlantic flight to Newfoundland, which would almost certainly be prolonged by headwinds, needed maximum fuel. There was no airfield in Ireland which had a sufficiently long runway for a take off with this load but there was a long beach at Porthmarnock, near Dublin, which they could use.

On the morning of 21 June, 1932 Scotty Allan opened the throttles to take off on the first leg of their epic round-the-world flight. After a run of 3,500 yards Faith left the ground. Their destination was the small town of Derby, on the coast of north western Australia. They flew steadily on all day across the desert of central Australia and into the night. Bill was at the controls when all three engines back fired – and stopped. It could only mean lack of fuel. The engines were fed from gravity tanks in the wings and they had run dry. Ulm rushed to the hand operated pump by the tanks in the cabin. Bill prepared for a forced landing in the dark. They ware saved from what would inevitably been a crash landing when, one by one, the engines coughed back to life.

Petrol fumes filled the cabin and they realised that there was a leak in the fuel lines. They had to pump continuously, taking 20 minute shifts, which was as long as they could stand in the noxious fumes. It was full daylight before Derby came into view. They landed and breathed clean air. It was just the first of the many problems they would suffer from in the course of their flight.

The leaking pump was replaced by an old, heavy but efficient rotary pump that had been used on a well and they set off on the next leg, an 1800 mile 16½ hour trouble free flight to Singapore. The journey to Rangoon was interrupted by a loose and vibrating cylinder on the starboard engine. They had to divert to an airfield in Malaya to fix it. At Rangoon, after a night of heavy rain, they were taxying out for take off and they ran into a patch of soft ground. The wheels sank in to the axle and Faith tipped forwards to almost 45º.

Luckily, the spinning propeller of the central engine stayed clear of the ground. The heavily loaded aeroplane crashed back, the tailskid drilled into the ground and Faith was sitting on its fuselage. Hours later, they were finally dug out and dragged to the end of the runway. They could no see no sign of any damage to the aeroplane so they left for the relatively short flight to Calcutta.

One of the aims of the flight had been to break the record for the Australia – England flight. The dismal progress so far was ruled this out. However they could make an impact on the Calcutta – London record with three long legs, stopping only in Karachi and Cairo.

Calcutta to Karachi went well. Over Persia, they flew into a tremendous dust storm. They tried to climb over it but the engines overheated. Allan reduced the throttles and Faith lost height. The port engine banged and misfired so Allan shut it down. They dumped fuel and headed for the nearest airfield. With the starboard engine showing signs of distress they landed at Jask. Ulm had not applied for permission to land in Persia so they were faced with a bureaucratic problem.

Using the spares he had brought, Allan replaced the piston in the port engine which had disintegrated. Several worn piston rings needed replacement. Four days later, Ulm was given permission for a ‘test flight’. They had enough fuel for the test flight to end in Basra in Iraq. They pressed on in short stages, nursing the engines until, over France, the starboard engine stopped and they landed at Orange, a military airfield. They gave up. Ulm cabled England and a Wright engine specialist arrived to rebuild the engines. He also fitted inertia starters and the hated platform was abandoned. They finally reached Heston on 9th July, 19 days since leaving Australia.

To their surprise they were warmly welcomed and given generous help in overhauling Faith and its troublesome engines. Bill was able to get a brand new RAF Mk VIII bubble sextant, much easier to operate than his own hand made prototype. He also had the compasses swung again.

The trans-Atlantic flight to Newfoundland, which would almost certainly be prolonged by headwinds, needed maximum fuel. There was no airfield in Ireland which had a sufficiently long runway for a take off with this load but there was a long beach at Porthmarnock, near Dublin, which they could use.

Drums were rolled up and fuel pumped into the tanks. Faith sank down on her shock absorbers. Refuelling completed, the empty drums were being rolled away when there was a loud cracking noise. The tie rod to the port undercarriage had broken, the wheel rolled forwards, and Faith crashed down. The wing tip was buried in the sand, the wing bent and fuel poured out of the broken tanks. The crowd rushed forward with a futile attempt to lift the wing. Nothing could be done and everyone had to retreat to allow the incoming tide to add its own measure of damage.

It all seemed to be over. Then, a telegram arrived from Lord Wakefield (of Castrol Motor Oil). He offered to pay for the extensive repairs to the aeroplane. The wreckage was shipped to Avro’s works in Manchester.

Bill was enjoying the break. He borrowed an Avro Tutor and was flying around England visiting old friends when he received two telegrams. The first told him that his brother Don, who was running the family business, had died. The second was from his mother, who insisted that he should carry on with the flight.

When the repairs were completed they flew Faith, in better condition than ever, to Brooklands to wait for suitable weather for the Atlantic leg. It didn’t turn up and as time passed, Ulm realised he couldn’t complete the flight before tenders had to be submitted for the air mail contract. To salvage something from the whole enterprise they left Brooklands on 12th October and flew back to Australia setting a new record of 7 days 17 hours, 20 minutes, despite having more engine problems on the way.

(Faith in Australia flew on for several years in Australia and New Zealand giving many people their first flying experience. In 1941 it evacuated many people from New Guinea in the face of the advancing Japanese).

Although Bill was a director and one of the owners of the family business and there was some pressure on him he was well aware that he was not competent or interested enough to take over from his brother, Don. One of the senior managers was appointed as Managing Director and Bill limited his contribution to attending the occasional board meeting. He joined forces with Kingsford Smith again.

Smithy had bought a Percival Gull in England and flew it to Australia in record time. His time of 7 days, 4 hours, 44 minutes was a solo record and even beat Faith’s record for multi-crewed aircraft.

Bill was enjoying the break. He borrowed an Avro Tutor and was flying around England visiting old friends when he received two telegrams. The first told him that his brother Don, who was running the family business, had died. The second was from his mother, who insisted that he should carry on with the flight.

When the repairs were completed they flew Faith, in better condition than ever, to Brooklands to wait for suitable weather for the Atlantic leg. It didn’t turn up and as time passed, Ulm realised he couldn’t complete the flight before tenders had to be submitted for the air mail contract. To salvage something from the whole enterprise they left Brooklands on 12th October and flew back to Australia setting a new record of 7 days 17 hours, 20 minutes, despite having more engine problems on the way.

(Faith in Australia flew on for several years in Australia and New Zealand giving many people their first flying experience. In 1941 it evacuated many people from New Guinea in the face of the advancing Japanese).

Although Bill was a director and one of the owners of the family business and there was some pressure on him he was well aware that he was not competent or interested enough to take over from his brother, Don. One of the senior managers was appointed as Managing Director and Bill limited his contribution to attending the occasional board meeting. He joined forces with Kingsford Smith again.

Smithy had bought a Percival Gull in England and flew it to Australia in record time. His time of 7 days, 4 hours, 44 minutes was a solo record and even beat Faith’s record for multi-crewed aircraft.

The Gull before it was re-registered VH-CKS and christened Miss Southern Cross. Kingsford Smith

Bill flew the Gull and immediately liked it. With its 130 hp Gipsy Major it cruised at 125 mph. He saw a way of earning money with it. In the early 30s some newspapers were experimenting sending pictures by wire but the results were crude and unsatisfactory. Only properly printed photographs could be used and the quickest way for them to travel was by air. Bill was soon flying between Australia’s major cities delivering photographs for the morning editions. On one occasion he flew to Surubaya in the East Indies to collect picture of the Ashes Test Match which had been flown from England by KLM.

The announcement of the Centenary Air Race for the MacRobertson Trophy captivated Smithy. He asked Bill to join him as navigator and second pilot and to help him find a suitable aeroplane. He’d heard that the Americans were entering a Boeing 247 and a Douglas DC-2, both twin engined with variable pitch propellers and retractable undercarriages. Sir Macpherson Robertson offered to buy him an aeroplane (he wanted an Australian to win the race) but insisted that it must be British. The only option seemed to be the Comet, three of which De Havilland were building especially for the race. Smithy ordered a fourth Comet.

Then he was told that DH had only three sets of Ratier two-pitch props. Smithy could have a Comet, but it would have fixed pitch propellers. That ruled it out. Smithy took ship to the US to search for a competitive racer.

Bill flew the Gull and immediately liked it. With its 130 hp Gipsy Major it cruised at 125 mph. He saw a way of earning money with it. In the early 30s some newspapers were experimenting sending pictures by wire but the results were crude and unsatisfactory. Only properly printed photographs could be used and the quickest way for them to travel was by air. Bill was soon flying between Australia’s major cities delivering photographs for the morning editions. On one occasion he flew to Surubaya in the East Indies to collect picture of the Ashes Test Match which had been flown from England by KLM.

The announcement of the Centenary Air Race for the MacRobertson Trophy captivated Smithy. He asked Bill to join him as navigator and second pilot and to help him find a suitable aeroplane. He’d heard that the Americans were entering a Boeing 247 and a Douglas DC-2, both twin engined with variable pitch propellers and retractable undercarriages. Sir Macpherson Robertson offered to buy him an aeroplane (he wanted an Australian to win the race) but insisted that it must be British. The only option seemed to be the Comet, three of which De Havilland were building especially for the race. Smithy ordered a fourth Comet.

Then he was told that DH had only three sets of Ratier two-pitch props. Smithy could have a Comet, but it would have fixed pitch propellers. That ruled it out. Smithy took ship to the US to search for a competitive racer.

He found a second hand Lockheed Altair. Fitted with a 500 hp P&W Wasp, v.p. prop and retractable undercarriage it had a cruising speed of 175 mph. Smithy had it modified with extra tanks and flaps. Tied down onto the tennis court of a liner it was taken to Australia. It was already July (1934) and it was scheduled to take off in the race from England on 20 October.

In his haste, Smithy had overlooked all the paperwork. He had no certificate of airworthiness and no permit to import the Altair into Australia. After much negotiation – and the influence of some friends in high places – Smithy was allowed to offload the Altair onto a barge and take it to a large park near the harbour. Obstructions were removed, Smithy and Bill climbed aboard and the Altair flew the short hop to Sydney’s airport. There it was wheeled into a hangar to have its new registration painted on (Smithy had at least applied for that) VH-USB - and its name Lady Southern Cross.

Permission was given – for a limited period – to allow a number of test flights to establish fuel consumption at different speeds. When all the tanks were filled the Altair was dangerously overweight so they had to seal off some of the extra tanks. It reduced their maximum range and would required more refuelling stops in the race. Nevertheless, in the tests they set up several inter-city records. Smithy worked on getting all the other certificates and permissions needed to enter the race. It wasn’t until 29th September that they learned that their entry had been accepted by the race committee.

They set off for England immediately, landing at Cloncurry in Queensland for an overnight stop. At the pre-flight inspection the next morning Smithy found a small crack at one of the cowling attachment points. They took the cowling off and found hidden cracks at every point. It was all over. They flew back to Sydney at reduced revs and a splendid new cowling was spun.

Kingsford Smith had been the object of much hero worship in Australia but with his withdrawal from the race his reputation was in tatters. Without knowing the facts, many accused him of cowardice. He even received a number of white feathers in the mail. He had an expensive aeroplane, the fastest commercial aircraft in the Southern Hemisphere and it sat in a hangar, doing nothing.

Suddenly, he brightened up. He said to Bill ‘Let’s have a go at the Pacific’ (i.e. Australia to the USA).

_____________________________________________

Crossing the Pacific - Australia to California

Unlike the MacRobertson race there were very few refuelling points for the flight, just Fiji and Hawaii with 3,150 miles between them. Smithy engaged Lawrence Wackett, a notable aeronautical engineer, to redesign the fuel tanks so they were better placed in relation to the centre of gravity. (One was added under Smithy’s seat). He also re-designed the oiling system to cope with that long leg.

Bill’s contribution would be crucial. He borrowed from Charles Ulm a Hughes P4 compass, in his opinion, the best in the world, and had it installed in the rear cockpit – Smithy would have a Sperry gyro compass. Lines for checking drift were painted on the tailplane and Bill had plenty of bags of aluminium powder to drop on the sea in daylight and flame floats for the night. His chronometer was mounted in rubber to counter any vibration. He had his essential sextant and every astronomical chart he might need. They did a final double run to check fuel consumption. It confirmed that at 1600 revs – 155 mph - at 5000 ft they would reach Hawaii with enough fuel for another 400 miles, provided, of course, that they were not hampered by headwinds.

It was 4 am on 20th October 1934 when they left Brisbane, aiming to arrive in Fiji in daylight. The coast was left behind almost immediately and there was only the sea below – nothing to check their position. At 0730, the sun was high enough for Bill to take his first shot. Smithy turned the Altair until the sun was abeam and Bill made sure everything was secure before opening his cockpit hood. The slipstream made his eyes water and he braced his elbow against the panel. When the bouncing bubble and the disc of the sun coincided Bill took a shot and noted the exact time on the chronometer. He took six more shots before closing the canopy. Smithy turned back on course and Bill began his calculations. They revealed that they were punching into a 25 mph headwind.

Hours later, they flew over some islands and recognised Noumea. Smithy radioed Fiji. They would be a little late in arriving, It could be dark.

They flew into a rain storm - heavy tropical rain. Suddenly, the engine erupted into a series of explosions. Smithy recognised the cause – the rain was shorting out some of the plugs. Bill worked out that they were almost exactly half way between Noumea and Fiji, 430 miles from safety. Smithy opened the throttle and dived. Once clear of the cloud the banging and vibration suddenly ceased. They flew on. Smithy often turned to avoid flying in heavy cloud and Bill struggled to keep track of the changes of course.

Permission was given – for a limited period – to allow a number of test flights to establish fuel consumption at different speeds. When all the tanks were filled the Altair was dangerously overweight so they had to seal off some of the extra tanks. It reduced their maximum range and would required more refuelling stops in the race. Nevertheless, in the tests they set up several inter-city records. Smithy worked on getting all the other certificates and permissions needed to enter the race. It wasn’t until 29th September that they learned that their entry had been accepted by the race committee.

They set off for England immediately, landing at Cloncurry in Queensland for an overnight stop. At the pre-flight inspection the next morning Smithy found a small crack at one of the cowling attachment points. They took the cowling off and found hidden cracks at every point. It was all over. They flew back to Sydney at reduced revs and a splendid new cowling was spun.

Kingsford Smith had been the object of much hero worship in Australia but with his withdrawal from the race his reputation was in tatters. Without knowing the facts, many accused him of cowardice. He even received a number of white feathers in the mail. He had an expensive aeroplane, the fastest commercial aircraft in the Southern Hemisphere and it sat in a hangar, doing nothing.

Suddenly, he brightened up. He said to Bill ‘Let’s have a go at the Pacific’ (i.e. Australia to the USA).

_____________________________________________

Crossing the Pacific - Australia to California

Unlike the MacRobertson race there were very few refuelling points for the flight, just Fiji and Hawaii with 3,150 miles between them. Smithy engaged Lawrence Wackett, a notable aeronautical engineer, to redesign the fuel tanks so they were better placed in relation to the centre of gravity. (One was added under Smithy’s seat). He also re-designed the oiling system to cope with that long leg.

Bill’s contribution would be crucial. He borrowed from Charles Ulm a Hughes P4 compass, in his opinion, the best in the world, and had it installed in the rear cockpit – Smithy would have a Sperry gyro compass. Lines for checking drift were painted on the tailplane and Bill had plenty of bags of aluminium powder to drop on the sea in daylight and flame floats for the night. His chronometer was mounted in rubber to counter any vibration. He had his essential sextant and every astronomical chart he might need. They did a final double run to check fuel consumption. It confirmed that at 1600 revs – 155 mph - at 5000 ft they would reach Hawaii with enough fuel for another 400 miles, provided, of course, that they were not hampered by headwinds.

It was 4 am on 20th October 1934 when they left Brisbane, aiming to arrive in Fiji in daylight. The coast was left behind almost immediately and there was only the sea below – nothing to check their position. At 0730, the sun was high enough for Bill to take his first shot. Smithy turned the Altair until the sun was abeam and Bill made sure everything was secure before opening his cockpit hood. The slipstream made his eyes water and he braced his elbow against the panel. When the bouncing bubble and the disc of the sun coincided Bill took a shot and noted the exact time on the chronometer. He took six more shots before closing the canopy. Smithy turned back on course and Bill began his calculations. They revealed that they were punching into a 25 mph headwind.

Hours later, they flew over some islands and recognised Noumea. Smithy radioed Fiji. They would be a little late in arriving, It could be dark.

They flew into a rain storm - heavy tropical rain. Suddenly, the engine erupted into a series of explosions. Smithy recognised the cause – the rain was shorting out some of the plugs. Bill worked out that they were almost exactly half way between Noumea and Fiji, 430 miles from safety. Smithy opened the throttle and dived. Once clear of the cloud the banging and vibration suddenly ceased. They flew on. Smithy often turned to avoid flying in heavy cloud and Bill struggled to keep track of the changes of course.

The lights were on in the buildings in Suva when they swung in to land in the last of the daylight. As they touched down the crowd rushed forward to greet them and Smithy hurriedly switched off the engine. It started to rain, everyone was soaked but they pulled Lady Southern Cross to the side of the field. A canvas cover was placed over the engine and cockpit.

It rained for three days, during which they fitted a new set of plugs. Also they found that the rain had worn and lifted some fabric from the leading edges of the wing. That was patched and re-doped. Albert Park, where they had landed was too short for a safe take off so Smithy flew the Altair to a beach. The long process of fuelling began, the petrol being hand-pumped from drums. There was some pressure because the tide was coming in and the strip of sand was narrowing. Then a greater problem faced them. The wind strengthened and it was blowing at 90ª to the take off run.

At last the engine was started and they taxied to the end of the beach. The four ton aeroplane accelerated slowly. The tail came up and, although Smithy held on full right rudder the Altair began to weather cock to the left towards the sea and the wheels splashed through the surf. Smithy closed the throttle and the Altair swung further into deeper water.

At last the engine was started and they taxied to the end of the beach. The four ton aeroplane accelerated slowly. The tail came up and, although Smithy held on full right rudder the Altair began to weather cock to the left towards the sea and the wheels splashed through the surf. Smithy closed the throttle and the Altair swung further into deeper water.

Immediately he slammed the throttle wide open. The tips of the propeller were in the water and the Altair was completely covered in spray. Smithy was able to swing round towards the beach. Bill could see nothing ahead, only the water swirling under the trailing edge of the wings. They burst out of the sea and spray and softening sand and taxied back to the fuelling point where there were boards on which the Altair could stand. The aeroplane and the whole adventure had been saved in that moment.

It was five days before the wind relented. On 29th October they had a trouble free take off and set course for Hawaii. Bill aimed for the island of Lauthala, 150 miles from Fiji to get a check on any drift. Then they ran into turbulent cloud and Smithy flew on instruments. Twenty minutes later the cloud cleared and they were in a truly pacific day, over a calm sea with excellent visibility to clear horizons.

The Altair was fitted with a drift sight which Bill did not normally use but when he looked through the celluloid window in the floor of his cockpit he was alarmed to see it streaked with a pale liquid. Was it petrol? He took the control column out of its socket and squirmed around to cut a hole in the window with his penknife. The celluloid was tough and the blade snapped. The knife had two blades and he used the second one more carefully. It was an awkward job but finally he prized open a little hole. He wetted his finger and tasted it. Thankfully, he tasted water. After a while the flow stopped. They were never able to work out where it had come from.

They were deep into the flight, in cloud, in heavy raid and in darkness. Smithy climbed in the hope of getting above the cloud. At 15,000 ft they were still in cloud. Smithy was concerned about the wings’ leading edges. Were they being damaged again by the continuous rain? From time to time he switched on the landing lights to check. Then Bill noticed that the airspeed had fallen to 90 mph. The engines were labouring but they were not flying at their usual 155 mph. And now they were losing height. The speed fell to 90 mph.

Suddenly, the Altair stalled and flicked into a spin. Smithy closed the throttle and the klaxon blared (as it does when the throttle is closed and the undercarriage retracted). The turn needle was hard over and the altimeter unwinding. Bill instinctively pushed on his rudder - to no effect. Smithy had already got it to the limit of its travel. ‘She won’t come out’ he shouted. 12,000 ft, 10,000, 8,000 . . The blaring spin went on. It might have been the increasing air density but at 7,000 ft the movement became smoother. ‘I think I’ve got her’ said Smithy. They were in a dive, the throttle opened and the klaxon fell silent. They levelled off at 6,000 ft, throttle wide open but still gently losing height. ‘Now I’ve got it’, he said. The revs began to rise and the airspeed crept back to 155 mph.

It was the flaps. When Smithy had flicked on the landing lights he had accidentally hit the switch which lowered the flaps and with the propeller in coarse pitch, the engine couldn’t keep up the revs. To add to the flood of relief in the cockpits, they flew out of the cloud, Bill looked at the stars and picked out Polaris. They had crossed the equator.

Bill got to work with his sextant. They were only 25 miles off course. The sun rose and at 8 o’ clock one of Hawaii’s islands rose above the horizon. Soon they were sweeping in to land at Wheeler Field, Honolulu.

The Altair was fitted with a drift sight which Bill did not normally use but when he looked through the celluloid window in the floor of his cockpit he was alarmed to see it streaked with a pale liquid. Was it petrol? He took the control column out of its socket and squirmed around to cut a hole in the window with his penknife. The celluloid was tough and the blade snapped. The knife had two blades and he used the second one more carefully. It was an awkward job but finally he prized open a little hole. He wetted his finger and tasted it. Thankfully, he tasted water. After a while the flow stopped. They were never able to work out where it had come from.

They were deep into the flight, in cloud, in heavy raid and in darkness. Smithy climbed in the hope of getting above the cloud. At 15,000 ft they were still in cloud. Smithy was concerned about the wings’ leading edges. Were they being damaged again by the continuous rain? From time to time he switched on the landing lights to check. Then Bill noticed that the airspeed had fallen to 90 mph. The engines were labouring but they were not flying at their usual 155 mph. And now they were losing height. The speed fell to 90 mph.

Suddenly, the Altair stalled and flicked into a spin. Smithy closed the throttle and the klaxon blared (as it does when the throttle is closed and the undercarriage retracted). The turn needle was hard over and the altimeter unwinding. Bill instinctively pushed on his rudder - to no effect. Smithy had already got it to the limit of its travel. ‘She won’t come out’ he shouted. 12,000 ft, 10,000, 8,000 . . The blaring spin went on. It might have been the increasing air density but at 7,000 ft the movement became smoother. ‘I think I’ve got her’ said Smithy. They were in a dive, the throttle opened and the klaxon fell silent. They levelled off at 6,000 ft, throttle wide open but still gently losing height. ‘Now I’ve got it’, he said. The revs began to rise and the airspeed crept back to 155 mph.

It was the flaps. When Smithy had flicked on the landing lights he had accidentally hit the switch which lowered the flaps and with the propeller in coarse pitch, the engine couldn’t keep up the revs. To add to the flood of relief in the cockpits, they flew out of the cloud, Bill looked at the stars and picked out Polaris. They had crossed the equator.

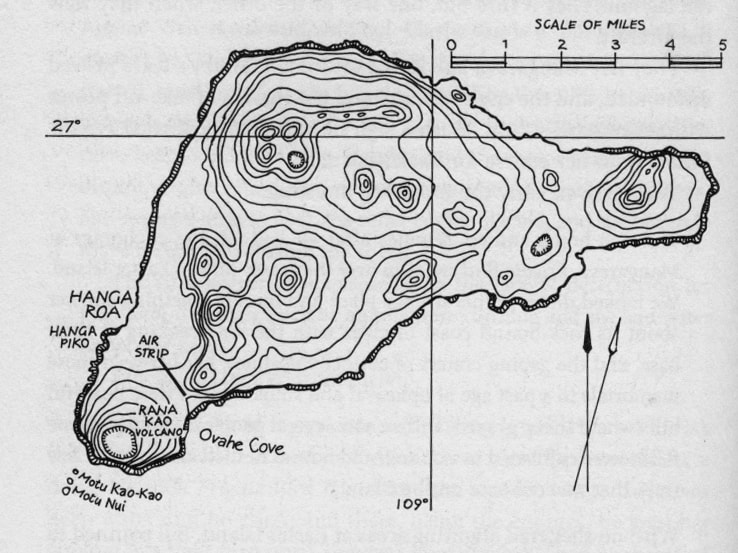

Bill got to work with his sextant. They were only 25 miles off course. The sun rose and at 8 o’ clock one of Hawaii’s islands rose above the horizon. Soon they were sweeping in to land at Wheeler Field, Honolulu.