Animals in Aviation (Aug 2013)

What part have animals played in man’s conquest of the air? Well, apart from the original example set by birds – exhaustively studied and as yet only partly emulated – we could start with the feathers collected by Daedalus or the hundreds of thousands of cows who donated their stomachs to make gas bags for airships. But let’s restrict this brief review to whole non-flying animals which actually took to the air.

Man’s first successful attempt to get off the ground began with the Mongolfier brothers. They made and tested small balloons which captured the magic ingredient which made hot air rise. When they got serious, they came to Paris in 1783 to demonstrate a larger version intended to carry men into the sky. But animals got there first. The real pioneers of air travel were a sheep (called Montauciel–‘climb to the sky’), a duck, which was unlikely to be harmed by ‘the sky’ and a rooster – a bird which didn’t fly at altitude. Only after their eight minutes of fame when they landed safely 3kms away were men allowed to get into the balloon.

Man’s first successful attempt to get off the ground began with the Mongolfier brothers. They made and tested small balloons which captured the magic ingredient which made hot air rise. When they got serious, they came to Paris in 1783 to demonstrate a larger version intended to carry men into the sky. But animals got there first. The real pioneers of air travel were a sheep (called Montauciel–‘climb to the sky’), a duck, which was unlikely to be harmed by ‘the sky’ and a rooster – a bird which didn’t fly at altitude. Only after their eight minutes of fame when they landed safely 3kms away were men allowed to get into the balloon.

Thereafter, in the casually regulated pioneering early years of aviation there were many instances of pilots flying with their pets. In WWI, several squadrons’ pet dogs are reputed to have enjoyed a brief flight inside their master’s coat. Other adopted pets were probably considered unsuitable – like the pet lion cub adopted by the American Escadrille Lafayette. Named ‘Whiskey’ – because he enjoyed a saucer-full of whiskey on a boy’s night out - his adopted keeper was Raoul Lufbery, the French-American ace. Whiskey followed him round like a pet dog but Lufbery never took him flying. However, in the post-war barnstorming era the flying lion was to become a reality.

After a few first flight nerves, Gilmore apparently enjoyed flying. The Irvin Parachute Company fitted him with his own parachute. When he and Roscoe were booked into hotels on their overnight stops Gilmore was often asked to leave his paw print in the register. They flew together for more than 25,000 miles until Gilmore’s increasing weight threatened to bring C.G problems and he was grounded.

A notable post-war aviator was the pet greyhound of Neville Browning. Neville flew in both world wars and built up a total of over 6000 flying hours. His disregard for regulations made him an entertaining display pilot, even at times when no display was scheduled. He had an aerobatic Zlin with fore and aft seating and the dog was strapped into the front seat. Whenever he visited another flying club he announced his arrival with a very low beat-up of the clubhouse. Naturally, Neville ducked down in the cockpit so the spectators could clearly see that the cavorting Zlin was being flown solo by a greyhound.

There are a couple of occasions when gliders carried animals. Having seen domestic hens occasionally flapping up to the roof of a shed, two glider pilots borrowed a couple ‘for an experiment’ to test their flying capabilities with the benefit of a few hundred feet of altitude. Chicken No 1 spread its wings and performed a decent circle before collapsing into a fluttering heap and tumbling to the ground. No. 2 made no attempt to fly and was seen disappearing downwards with its eyes closed. Happily, the drag of a fluttering chicken is considerable and their ‘landings’ were untidy but gentle enough for them to be smuggled back into the chicken run with no visible sign of their misadventure.

The other animal glide took place back in the ‘60s in Yugoslavia when a club sold one of its gliders. The new owner wanted to avoid the tortured road network – he had no trailer anyway – and arranged an aerotow which would take less than an hour. Cruising steadily at 3000’ he was surprised to feel something rubbing on the back of his neck. He looked round just in time to see the tail of a snake disappearing into the wing root. Self-preservation took immediate effect. Releasing the tow-rope, he put the glider into a steep snake-wing-down spiral and looked for somewhere to land. In the rough mountainous country landing places were few and too small for the tug. He was out of the cockpit before the glider stopped rolling and before any reappearance of the snake. The ‘1-hour retrieve’ turned into a week-long marathon.

There are a couple of occasions when gliders carried animals. Having seen domestic hens occasionally flapping up to the roof of a shed, two glider pilots borrowed a couple ‘for an experiment’ to test their flying capabilities with the benefit of a few hundred feet of altitude. Chicken No 1 spread its wings and performed a decent circle before collapsing into a fluttering heap and tumbling to the ground. No. 2 made no attempt to fly and was seen disappearing downwards with its eyes closed. Happily, the drag of a fluttering chicken is considerable and their ‘landings’ were untidy but gentle enough for them to be smuggled back into the chicken run with no visible sign of their misadventure.

The other animal glide took place back in the ‘60s in Yugoslavia when a club sold one of its gliders. The new owner wanted to avoid the tortured road network – he had no trailer anyway – and arranged an aerotow which would take less than an hour. Cruising steadily at 3000’ he was surprised to feel something rubbing on the back of his neck. He looked round just in time to see the tail of a snake disappearing into the wing root. Self-preservation took immediate effect. Releasing the tow-rope, he put the glider into a steep snake-wing-down spiral and looked for somewhere to land. In the rough mountainous country landing places were few and too small for the tug. He was out of the cockpit before the glider stopped rolling and before any reappearance of the snake. The ‘1-hour retrieve’ turned into a week-long marathon.

Guide dogs are allowed to sit uncaged beside their owner. Larger animals are checked in as ‘live cargo’ and travel in the forward section of the hold. It’s a pressurised area but not normally heated. The pilots usually have to control the temperature manually by switches in the cockpit. Pilots of private planes are not so regulated and just use commonsense - well, they usually do. One couple bought a pair of pedigree cats and loaded the cage into the back seat of their Mooney. The cats were so calm and quiet that the pilot’s wife thought she could let them out of the cage. Freedom brought fury and the cats leapt all over the cockpit, scratching and clawing the pilot and his wife, who fought them off as they diverted quickly to the nearest airport. An unrestrained animal caused problems in a similar aeroplane when the pilot put his quiet, well-behaved Alsatian on the rear seat. All was well for a time until the pilot found it difficult to keep the aeroplane in trim. The 70 lbs dog had climbed onto the parcel shelf behind the luggage area (max wt. allowed -10 lbs).

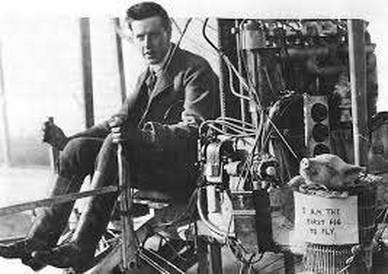

The picture on the right is of an owner-pilot who is a member of an association of regular animal-carriers called Pilots N Paws, a volunteer group who perform pet rescue flights. 2500 pilots in the US are members and one has carried 1000 animals.

In many parts of the world the aeroplane is a workhorse and animals often appear on the cargo manifest. Live goats crates of baby alligators, large turtles, can leave a lasting impression. After landing the smell surges forward into the cockpit and even when the cargo is unloaded there’s a thankless cleaning job to be done. In the ‘50s there was sufficient demand in the USA for monkeys to support an active trade into Florida. The import of live monkeys was allowed but dead monkeys generated a mountain of paperwork and trouble. It became part of the co-pilot’s pre-landing checklist to search the aeroplane and throw out any animal which had not survived the journey. When one of these unfortunates landed with a splat on a table of a government official’s garden party there was an immediate crackdown and the monkey business ceased to be profitable. Which leads conveniently to the final tale in this animal saga which, however unlikely, has to be included.

Some years ago a Japanese Coast Guard vessel rescued the crew of a fishing boat who were floating on a raft. They told an incredible story that their boat had been sunk by a cow which had fallen from the sky and smashed their boat which sank in minutes. Naturally, they were not believed. They were suspected of trying to work some insurance scam and were thrown into jail. They stayed there for some weeks, refusing to change their story which soon got a considerable airing in the press. This could have helped the truth to emerge.

A Russian Air Force cargo plane had visited an airstrip in Siberia when a cow wandered onto the strip. The crew saw this as a beef supply opportunity and persuaded the cow to walk up the ramp into the hold of their plane. But the cow didn’t take to flying and soon began to charge about causing considerable damage. The crew decided that their safety and even survival was more important than the beef so they lowered the ramp and pulled into a steep climb. At the time, they were over the Sea of Japan . . .

Some years ago a Japanese Coast Guard vessel rescued the crew of a fishing boat who were floating on a raft. They told an incredible story that their boat had been sunk by a cow which had fallen from the sky and smashed their boat which sank in minutes. Naturally, they were not believed. They were suspected of trying to work some insurance scam and were thrown into jail. They stayed there for some weeks, refusing to change their story which soon got a considerable airing in the press. This could have helped the truth to emerge.

A Russian Air Force cargo plane had visited an airstrip in Siberia when a cow wandered onto the strip. The crew saw this as a beef supply opportunity and persuaded the cow to walk up the ramp into the hold of their plane. But the cow didn’t take to flying and soon began to charge about causing considerable damage. The crew decided that their safety and even survival was more important than the beef so they lowered the ramp and pulled into a steep climb. At the time, they were over the Sea of Japan . . .

PS And when man decided to go into space, who led the way?