The Comper Swift (Feb 2010)

Being asked to pick a favourite from Shuttleworth’s collection of aviation exotica induces a flurry of regretful rejections. How could anyone not choose the racy red Comet, or the incomparable Spitfire, or the shining Hind, or one of the delicate Edwardians or . . . . . All right then, draw up your own short list of, say, five and let’s compare notes. It’s safe to say that one little jewel that would get a frequent mention in most enthusiasts’ lists is the Comper Swift.

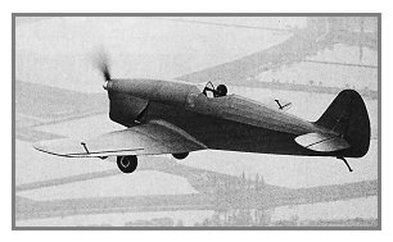

Sitting in one of Old Warden’s gloomier hangars It has the advantage of being an eye-catching red highlight: the ‘competition’ is currently an over-shadowed black and orange flying suitcase (the cars and Dorothy the steam engine have their own charm but they’re in quite a different league). Maybe its comparative isolation from most of the other aeroplanes is deliberate. Wherever it was, it would outshine its fellows. With a span of just 26 ft it sits there at a perky angle, its racing origins emphasised by hunched muscular shoulders. The neat radial engine, an object of elegant design in its own right, perfectly complements the Swift’s urgent lines. The whole diminutive, glowing, cheeky package oozes desirability.

Sitting in one of Old Warden’s gloomier hangars It has the advantage of being an eye-catching red highlight: the ‘competition’ is currently an over-shadowed black and orange flying suitcase (the cars and Dorothy the steam engine have their own charm but they’re in quite a different league). Maybe its comparative isolation from most of the other aeroplanes is deliberate. Wherever it was, it would outshine its fellows. With a span of just 26 ft it sits there at a perky angle, its racing origins emphasised by hunched muscular shoulders. The neat radial engine, an object of elegant design in its own right, perfectly complements the Swift’s urgent lines. The whole diminutive, glowing, cheeky package oozes desirability.

The Swift was one of the designs to the credit of Flt. Lt. Nick Comper. At the age of seventeen he began work with Geoffrey de Havilland’s Aircraft Manufacturing Company until being released in 1916 to join the Royal Flying Corps. He flew B.E.2cs as a reconnaissance pilot and after the war studied aerodynamics at Cambridge. In 1922 he was posted to RAF Cranwell as an instructor in the metallurgical laboratory. He formed a model club, which became a glider club and then the Cranwell Light Aeroplane Club.

Comper designed several aeroplanes for the cadets to build in their spare time. The first to be completed, the C.L.A. 2, powered by a 32 hp Bristol Cherub, won the Reliability Prize at the Air Ministry’s Lympne Trials in 1924. One of the constructors was a Cadet Frank Whittle who had his first flight with Comper in the C.L.A.2.

Comper designed several aeroplanes for the cadets to build in their spare time. The first to be completed, the C.L.A. 2, powered by a 32 hp Bristol Cherub, won the Reliability Prize at the Air Ministry’s Lympne Trials in 1924. One of the constructors was a Cadet Frank Whittle who had his first flight with Comper in the C.L.A.2.

C.L.A.2 C.L.A.4 (with Bristol Cherub engine).

At about this time, a newly-arrived officer, Captain Douglas Pobjoy, was posted to Cranwell. Impressed by the success of the Club’s work he designed and built a 7-cylinder radial engine which would be suitable for their designs. It was fitted to the C.L.A. 4 for the 1926 Trials but there was insufficient time to complete the testing of the design before the Trials started.

At about this time, a newly-arrived officer, Captain Douglas Pobjoy, was posted to Cranwell. Impressed by the success of the Club’s work he designed and built a 7-cylinder radial engine which would be suitable for their designs. It was fitted to the C.L.A. 4 for the 1926 Trials but there was insufficient time to complete the testing of the design before the Trials started.

Flt Lt Nick Comper

Flt Lt Nick Comper

In 1926 it all came to an end when the Boys’ Wing became the Apprentices’ Wing and moved from Cranwell to Halton. Comper was posted to Felixstowe. In 1929 he resigned his commission and formed the Comper Aircraft Company at Hooton Park in Cheshire to build the C.L.A. 7, the Swift. One of the directors of the new company was Richard Shuttleworth.

The prototype Swift first flew on 16 April 1930, powered by a 50 hp Salmson radial engine. It was advertised as the world’s smallest light aircraft. With clean aerodynamics it could achieve over 100 mph, was fitted with folding wings and even had space to carry a set of golf clubs. When the Pobjoy engine was installed orders flowed in from 14 different countries.

The prototype Swift first flew on 16 April 1930, powered by a 50 hp Salmson radial engine. It was advertised as the world’s smallest light aircraft. With clean aerodynamics it could achieve over 100 mph, was fitted with folding wings and even had space to carry a set of golf clubs. When the Pobjoy engine was installed orders flowed in from 14 different countries.

Soon, all the major air races had Swifts competing – they were in every King’s Cup from 1930 to 1937 – and Swifts completed some remarkable long-distance flights.

Charles Butler flew one to Australia in 1931 in a record 9 days, 2 hours and 29 minutes; Lt Cdr, C Byas flew to Cape Town in 10 days, Cyril Taylor crossed the Andes to Chile, reaching 18,000 ft without oxygen in the process and Richard Shuttleworth flew his Swift to India to take part in the 1931 Viceroy’s Challenge Cup Air Race in Delhi.

Competing in the same race was the Swift VT-ADU of Alban Ali, a tea planter. Afterwards he set off to fly to the UK but the damage caused by a forced landing near Gaza meant that it finished its journey by sea. Later it was sold, re-registered G-ACTF and passed through the hands of several owners. In time it took part in the 1950 Daily Express race finishing with an average speed of 141 mph. Today it sits proudly in Shuttleworth’s hangar. In all, 41 Swifts were built, most with a 75 or 90 hp Pobjoy engine. In a quest for even more speed three were fitted with more powerful Gipsy engines. One of them achieved 185 mph.

After the Swift, Comper produced the Streak, essentially a low-wing Swift with retractable undercarriage. There was also the Kite, a two-seat version. In a different category was the Mouse, an efficient three-seat cabin monoplane with retractable undercarriage and a cruising speed of 130 mph. None of these went into production.

After the Swift, Comper produced the Streak, essentially a low-wing Swift with retractable undercarriage. There was also the Kite, a two-seat version. In a different category was the Mouse, an efficient three-seat cabin monoplane with retractable undercarriage and a cruising speed of 130 mph. None of these went into production.

The Streak – with undercarriage lowered The Kite. Here the second cockpit is faired over

The Mouse, named after Comper’s friend E.H. ‘Mouse’ Fielden, later Air Commodore and Captain of the King’s Flight

Nick Comper’s business acumen failed to complement his talents as an aircraft designer. The company struggled to attract sales in a difficult market throughout the depressed 30s. Several promotion schemes failed and there was no-one to provide the essential financial control of the business.

It all came to a bizarre end in June, 1939. Both the company’s and Comper’s finances were in a dreadful state – he’d even suffered the indignity of having his gas and electricity cut off. Visiting a pub in Hythe he thought it would be a good joke to let off a firework. The landlord dissuaded him. Outside the pub he struggled with his lighter and a passer-by asked what he thought he was doing. He apparently replied that he was an IRA man about to blow up the Town Hall. At which, the other man hit him. Comper fell, striking his head. He suffered a brain haemorrhage and died next day in hospital.

It all came to a bizarre end in June, 1939. Both the company’s and Comper’s finances were in a dreadful state – he’d even suffered the indignity of having his gas and electricity cut off. Visiting a pub in Hythe he thought it would be a good joke to let off a firework. The landlord dissuaded him. Outside the pub he struggled with his lighter and a passer-by asked what he thought he was doing. He apparently replied that he was an IRA man about to blow up the Town Hall. At which, the other man hit him. Comper fell, striking his head. He suffered a brain haemorrhage and died next day in hospital.

Comper’s work lives on today in the surviving Swifts. The small airworthy group include G-ACTF at Old Warden; VH-ACG which flew again after restoration in 2008 and turned heads at Oshkosh in 2009 ; and in Spain, EC-AAT flies on the first Sunday of every month, painted in the colours which commemorate a Swift’s flight from Madrid to Manila in 1933. Four other non-airworthy Swifts are stored in the UK, France, Australia and Argentina.

In 2008, the remains of another Swift were found in a garage in Manchester. It is believed to be the one on which Alex Henshaw began his racing career in 1933 and is now with the RAF Museum in Stafford. One day, perhaps?

In 2008, the remains of another Swift were found in a garage in Manchester. It is believed to be the one on which Alex Henshaw began his racing career in 1933 and is now with the RAF Museum in Stafford. One day, perhaps?

In the early 90s a new Swift, G-LCGL, was built from scratch by John Greenland after much research and work in updating the plans. Further progress on these has resulted in all 229 plans now being available on a CD. A telling endorsement of the design is that new Swifts are currently under construction, here in the UK under the auspices of the Light Aircraft Association, in the USA, Australia and in Spain. This is not a project to be undertaken lightly. The Swift might appear to be a small symphony of spruce but underneath lurk no fewer than 800 metal fittings, some extremely complicated works of art. Help is at hand. A small company in Grimsby can produce most of the fittings – for a price – and considers Comper’s engineering as ‘absolutely exquisite’.

Finally, we can find no explanation for this genuine address - Comper Swift Close, Sutton-On-Sea, Mablethorpe.

____________________________________________________

Post Script - 13 years post!

A reader of this article, who knew Alex Henshaw in later years, had told us that Alex gave up flying in 1948 and went home to Lincolnshire to help run his family's farming and other businesses. He developed a small estate of houses in Sutton-on-Sea.

Thank you Gordon.

In the Sandilands area of Sutton, where Alex used to live, there is Henshaw Avenue, whose nameboard (it's more a plaque than a nameboard) carries images of his Mew Gull G-AEXF and an anonymous Spitfire. (The Spitfire, of course, commemorates Henshaw's time as Chief Test Pilot at the Castle Bromwich shadow factory where 11,000 Spitfires were built. He personally tested at least 10% of them and was awarded the MBE). Roads off Henshaw Avenue lead to Comper Swift Close, Leopard Moth Close, and Mew Gull Drive

Finally, we can find no explanation for this genuine address - Comper Swift Close, Sutton-On-Sea, Mablethorpe.

____________________________________________________

Post Script - 13 years post!

A reader of this article, who knew Alex Henshaw in later years, had told us that Alex gave up flying in 1948 and went home to Lincolnshire to help run his family's farming and other businesses. He developed a small estate of houses in Sutton-on-Sea.

Thank you Gordon.

In the Sandilands area of Sutton, where Alex used to live, there is Henshaw Avenue, whose nameboard (it's more a plaque than a nameboard) carries images of his Mew Gull G-AEXF and an anonymous Spitfire. (The Spitfire, of course, commemorates Henshaw's time as Chief Test Pilot at the Castle Bromwich shadow factory where 11,000 Spitfires were built. He personally tested at least 10% of them and was awarded the MBE). Roads off Henshaw Avenue lead to Comper Swift Close, Leopard Moth Close, and Mew Gull Drive