The RAF in Somalia (May 2020)

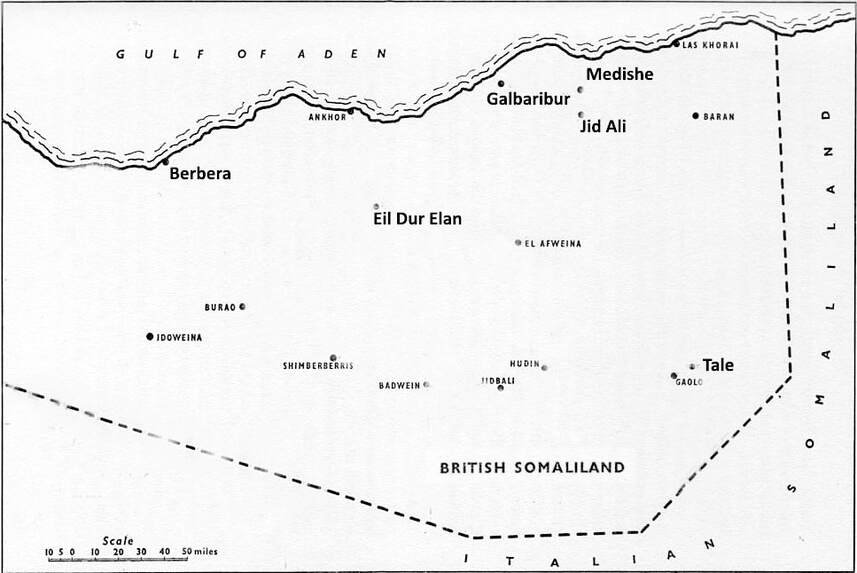

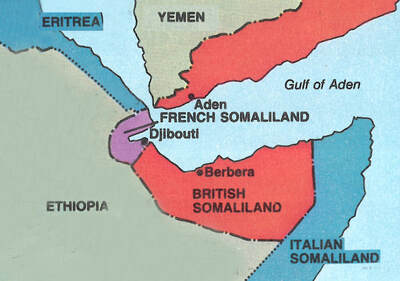

Somalia is on the coastal fringe of the Horn of Africa. In the ‘scramble for Africa’ in the 19th century European countries had established trading ports and there was the potential for conflict, even military action, between the Europeans. Common sense prevailed and in 1884 France, Britain and Italy agreed to define the areas of Somalia which would be allocated to each country. Somaliland became a ‘Protectorate’, well, three Protectorates and a number of treaties were signed with local tribal leaders.

The coastal area of British Somaliland is largely desert with no vegetation and merciless heat. Inland, the ground rises to a cooler 3,000 ft where cattle can graze and some crops grown (the Somalis suppled the meat for the growing British garrison at Aden).

The coastal area of British Somaliland is largely desert with no vegetation and merciless heat. Inland, the ground rises to a cooler 3,000 ft where cattle can graze and some crops grown (the Somalis suppled the meat for the growing British garrison at Aden).

The population are staunchly Muslim and sit uneasily with their Ethiopean neighbours to the south. They were even less comfortable with any Christians in their territory and there were stirrings of militant resistance.

The most prominent rebellious group was led by Sayyid Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, a Mullah (i.e. one educated in Islamic law). He was a natural leader, clever, charismatic and a renowned poet, although British troops referred to him as the ‘Mad Mullah’. He assembled a strong force of fighters, the Dervishes, and his jihad against the British began in 1899. He fought a roving war and a number of expeditions to control him all failed. Even a pitched battle in 1913 was a clear defeat for the British forces. As his influence over the country grew Hassan established a number of forts, or strongpoints, principally to control the very limited water supply. He tightened his grip on the population. Any hint of siding with the British brought severe punishment and he extracted ‘protection money’ from all the local tribes.

The most prominent rebellious group was led by Sayyid Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, a Mullah (i.e. one educated in Islamic law). He was a natural leader, clever, charismatic and a renowned poet, although British troops referred to him as the ‘Mad Mullah’. He assembled a strong force of fighters, the Dervishes, and his jihad against the British began in 1899. He fought a roving war and a number of expeditions to control him all failed. Even a pitched battle in 1913 was a clear defeat for the British forces. As his influence over the country grew Hassan established a number of forts, or strongpoints, principally to control the very limited water supply. He tightened his grip on the population. Any hint of siding with the British brought severe punishment and he extracted ‘protection money’ from all the local tribes.

In 1919, most of the fighting in the Empire had ended but Somalia was still neither a peaceful nor a controlled country. In Westminster the Government’s Colonial Secretary determined, yet again, that ‘something must be done’ about it.

And that something could only be another expedition - a proper one this time.

And that something could only be another expedition - a proper one this time.

The local forces on the ground included three companies of the Camel Corps, using the best vehicle for the terrain – best shod, low maintenance, minimal fuel consumption. Less mobile were five companies of the King’s African Rifles and a small number of Indian Grenadiers, largely employed on garrison duties. There were also several hundred Somali levies recruited from ‘friendly’ tribes, though it was reputed to be difficult to control in idleness a group of nomadic professional looters. The most valuable and critical contribution theses forces could make was local knowledge, of the country and the people.

For a properly organised expedition to defeat Hassan and his 3,500 (estimated) Dervishes it was proposed that it would need at least two divisions of troops – that’s about 5000 men - accompanied by mobile artillery and supported by six warships. Roads would have to be constructed, possibly even railways. The CIGS (Chief of the Imperial General Staff, who sits at the peak of the pyramid of military power) calculated that this would cost over two million 1919 pounds, something which a country almost bankrupted by the war could not afford. A decision would need to be taken quickly because the ‘fighting season’ would soon be over. Serious military activity in Somalia is possible only from December to March when the north easterly winds of the monsoon bring cooler air from the sea to temper the searing heat of the sun.

It was the surprising plan put forward by the Chief of the Air Staff which emerged as a silver bullet. Air Marshal Trenchard proposed that, with little more than some help from the forces in the area the RAF would defeat the Dervishes with a bombing campaign. No one else had much faith in this plan but its outstanding merit was that it was cheap. If it failed nothing much would have been lost, though the Army cynically expected they would still be needed to clear up the mess. The plan was given full and almost immediate approval.

Preparations were made in secret. Force Z was formed, commanded by Acting Group Capt Robert Gordon DSO. He and his deputy, a medical officer and a number of airfield construction specialists left the UK in October 1919 as an advance party, travelling in civilian clothes by commercial shipping. From Aden, they travelled by Arab dhow to Berbera, the Somaliland capital, as ‘oil experts’. Accompanied by a liaison officer with some knowledge of the country they searched, not for drilling sites, but for possible locations to build airstrips.

At Berbera, the main port, over 500 locals were hired as labourers to clear rocks, humps and bushes from an area 400 x 200 yards. This was to be the base for the operation. Gordon had found two or three reasonably flat areas of ground with water sources nearby mid-way between Berbera and Hassan’s largest forts.

It was the surprising plan put forward by the Chief of the Air Staff which emerged as a silver bullet. Air Marshal Trenchard proposed that, with little more than some help from the forces in the area the RAF would defeat the Dervishes with a bombing campaign. No one else had much faith in this plan but its outstanding merit was that it was cheap. If it failed nothing much would have been lost, though the Army cynically expected they would still be needed to clear up the mess. The plan was given full and almost immediate approval.

Preparations were made in secret. Force Z was formed, commanded by Acting Group Capt Robert Gordon DSO. He and his deputy, a medical officer and a number of airfield construction specialists left the UK in October 1919 as an advance party, travelling in civilian clothes by commercial shipping. From Aden, they travelled by Arab dhow to Berbera, the Somaliland capital, as ‘oil experts’. Accompanied by a liaison officer with some knowledge of the country they searched, not for drilling sites, but for possible locations to build airstrips.

At Berbera, the main port, over 500 locals were hired as labourers to clear rocks, humps and bushes from an area 400 x 200 yards. This was to be the base for the operation. Gordon had found two or three reasonably flat areas of ground with water sources nearby mid-way between Berbera and Hassan’s largest forts.

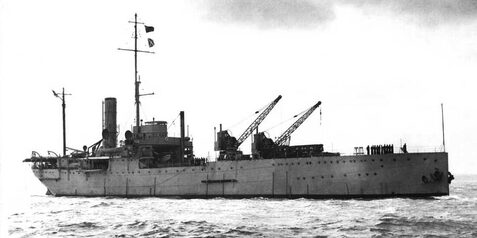

The main party travelled to Egypt where they joined the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal. They arrived at Berbera at the end of December. Twelve DH9As in crates were off-loaded together with 36 officers, 183 airmen, a dozen vehicles and 800 tons of supplies. Assembly of the aircraft began the next morning. It was New Year’s Day, 1920.

It was not easy. The monsoon blew strongly for at least six hours a day, raising clouds of a dirty brown sandstorm 2-300 feet high. To provide some shelter screens were built, 12 feet high and 50 yards long, behind which three machines could shelter. Other screens of rush matting were made to shield the men and the aeroplanes from direct sunlight.

As the DH 9As were assembled they were air-tested and prepared for operations. The final check was compass swinging. The available maps were unreliable, inaccurate and little use for navigating. ‘Roads’ were mostly camel tracks and landmarks were few. Pilots would have to navigate by compass course almost as though they were flying over the sea. So the aeroplanes were fully loaded with fuel, armaments and bombs with the pilots and observers sitting in the cockpits. Then the compasses were carefully swung.

One bomber was converted into an air ambulance. A shell was fitted above the rear fuselage to take a stretcher. The increased side area did nothing for its flying characteristics. It interfered with airflow over the rudder and flew ‘like a squirrel’. Despite this, it proved to be very useful in the later stages of the campaign.

By 19 January, fuel supplies had been dumped at the ‘advanced landing ground’ at Eil Dur Elan and eight DH 9As left to fly there. One turned back with engine trouble but caught up the next day.

On 21 January, operations began. To maximise the element of surprise they was no preliminary reconnaissance. Six aeroplanes flew off to attack the fort at Medishe where Hassan was believed to be. He was aware that British forces were being assembled to attack him but he was completely unaware of the presence of aeroplanes or even what an aeroplane did. He had never seen one before and when the first Nine-Ack appeared those of his followers who had some idea of what was likely to happen wouldn’t tell him – the penalty of delivering bad news was death. Then the first of eight 20 lb bombs fell. They did little material damage but one fell close enough to the Mullah to singe his clothing and kill his uncle. Many others died when the observer emptied two drums of ammunition onto the crowd of Dervishes.

The shock of this new form of warfare was delivered by just one bomber. The others in the formation had succumbed to the difficulties of navigation and failed to find the fort at Medishe. Four of them did come across a fort – at Jid Ali. They attacked that, machine gunning the Dervishes and their herds of stock. The sixth DH 9A overshot the target, had engine problems and force landed near the coast. Luckily, the crew were able to fix the fault and fly back home.

The shock of this new form of warfare was delivered by just one bomber. The others in the formation had succumbed to the difficulties of navigation and failed to find the fort at Medishe. Four of them did come across a fort – at Jid Ali. They attacked that, machine gunning the Dervishes and their herds of stock. The sixth DH 9A overshot the target, had engine problems and force landed near the coast. Luckily, the crew were able to fix the fault and fly back home.

These two pictures were taken (at 8,000 ft) on the way to the attacks on the forts. One of them was taken by the observer in one of the DH9s, Oswald Gayford. (His name has appeared before in this pages – in November 2019.

He was one of the pilots who captured the world long distance record in 1933 and he also

commanded the unit which took the record again in 1938).

He was one of the pilots who captured the world long distance record in 1933 and he also

commanded the unit which took the record again in 1938).

The following day, four bombers set out to attack Medishe. One returned with engine trouble, the other three failed to find Medishe because of low cloud but they saw Jid Ali and attacked that again. In the afternoon two more left for Medishe, one turned back (engine again) but the other got there and bombed one of Medishe’s three forts.

Although there was no significant damage to the forts Mullah Hassan had got the message and moved with his family into a nearby cave. The bombers returned again in the following days and every time found fewer Dervishes to attack. They seemed to have melted away. They were assumed to be heading south towards the Mullah’s main forts at Tele. The RAF tracked them as best they could flying contact patrols finding small groups hiding in wadis. They dropped messages – and used radio where they could – to the ground forces, the Camel Corps, the Rifles and the levies. The levies had almost doubled in strength. A flood of volunteers had emerged, eager to join now that there was real fighting to be done.

Others keen to join the fray were the sailors of the Royal Navy. Although the story of their contribution has absolutely nothing to do with the RAF’s efforts, it deserves to be told. The two frigates which accompanied Ark Royal sailed east from Berbera until they were close to the fort at Gabaribur. No doubt they remembered how sailors had man-handled guns over rough terrain to help in the relief of the siege of Ladysmith in the Boer War in 1899. It could be done again. A 12 pounder gun with 100 sailors, sundry machine guns and rifles and four days rations were landed on shore. Preparations included staining their white uniforms in coffee and making a caterpillar track for the gun’s wheels.

100 locals were recruited, including a number of donkeys and their drivers. It was a somewhat chaotic convoy that pushed on towards their first overnight camp. It took another day’s hard slog to reach the fort.

Although there was no significant damage to the forts Mullah Hassan had got the message and moved with his family into a nearby cave. The bombers returned again in the following days and every time found fewer Dervishes to attack. They seemed to have melted away. They were assumed to be heading south towards the Mullah’s main forts at Tele. The RAF tracked them as best they could flying contact patrols finding small groups hiding in wadis. They dropped messages – and used radio where they could – to the ground forces, the Camel Corps, the Rifles and the levies. The levies had almost doubled in strength. A flood of volunteers had emerged, eager to join now that there was real fighting to be done.

Others keen to join the fray were the sailors of the Royal Navy. Although the story of their contribution has absolutely nothing to do with the RAF’s efforts, it deserves to be told. The two frigates which accompanied Ark Royal sailed east from Berbera until they were close to the fort at Gabaribur. No doubt they remembered how sailors had man-handled guns over rough terrain to help in the relief of the siege of Ladysmith in the Boer War in 1899. It could be done again. A 12 pounder gun with 100 sailors, sundry machine guns and rifles and four days rations were landed on shore. Preparations included staining their white uniforms in coffee and making a caterpillar track for the gun’s wheels.

100 locals were recruited, including a number of donkeys and their drivers. It was a somewhat chaotic convoy that pushed on towards their first overnight camp. It took another day’s hard slog to reach the fort.

The Dervishes had burnt the huts and scrub around the fort to give themselves a clear field of fire. When the Navy advanced their bugle calls were answered by conch shells being blown in defiance.

The hail of machine guns and even the exploding shells of the gun had little effect on the 5 ft thick walls of the fort.

In a lull in the attack one man came out to say that there were women and children in the fort. They were allowed to be led away.

The hail of machine guns and even the exploding shells of the gun had little effect on the 5 ft thick walls of the fort.

In a lull in the attack one man came out to say that there were women and children in the fort. They were allowed to be led away.

Soon more ammunition was needed. A heliograph had been rigged up and the ships were signalled to send shells. The donkeys which collected them returned at 0300 hours the next day. Their loads included a number of solid, non-exploding practice shots. They did the trick.

At dawn, the solid shots were fired and the walls began to crumble. When the attackers stormed through the breach the 15 defenders all fought to their death. There was no naval casualty. More women and children were found in the fort along with a dozen sheep and goats. The latter supplemented the rations for a celebratory feast which went on rather late and was accompanied by energetic Somali dances. Next day the sailors returned to their ships. The hired locals were paid off and took the ‘captured’ animals.

At dawn, the solid shots were fired and the walls began to crumble. When the attackers stormed through the breach the 15 defenders all fought to their death. There was no naval casualty. More women and children were found in the fort along with a dozen sheep and goats. The latter supplemented the rations for a celebratory feast which went on rather late and was accompanied by energetic Somali dances. Next day the sailors returned to their ships. The hired locals were paid off and took the ‘captured’ animals.

It is 120 miles from Medishe/Jid Ali to Tale and the groups of Dervishes were scattered over a wide swathe of the semi-desert. The RAF flew search patrols, navigating carefully and updating their maps. They also needed to keep track of the Camel and Rifle units who zig-zagged about from one contact report to the next. The forces used ground and smoke signals, the Nine-Acks dropped messages and occasionally would land where the surface was suitable. It was now that the air ambulance came into its own, evacuating casualties.

The Mullah’s baggage column was spotted and attacked from the air. Later it transpired that the column was made up of the Mullah’s personal followers, his headmen and their families. The Mullah himself was only a couple of miles away. He had escaped again.

It was a punishing pursuit. The ground forces soon began to run out of food although it didn’t seem that water would be a problem. It was the ‘rainy’ season and there were puddles in the wadis after the last shower. However, it quickly became apparent that the water was not potable and many of the troops and particularly the British officers, suffered from bouts of violent vomiting and diarrhea. Both men and animals were seriously in need of a rest and food. They revived sufficiently to capture a large group they found in a wadi. It consisted mostly of women and children and included one of the Mullah’s wives. The guards all died in the defence of the women whose screams and shouts almost drowned out the rifle shots.

As the forces closed in on Tale they learned of tribal leaders deserting the Mullah. One defector was one of the Mullah’s many sons who approached the force and told them exactly where his father was, warning that he was about to move on soon.

It was a punishing pursuit. The ground forces soon began to run out of food although it didn’t seem that water would be a problem. It was the ‘rainy’ season and there were puddles in the wadis after the last shower. However, it quickly became apparent that the water was not potable and many of the troops and particularly the British officers, suffered from bouts of violent vomiting and diarrhea. Both men and animals were seriously in need of a rest and food. They revived sufficiently to capture a large group they found in a wadi. It consisted mostly of women and children and included one of the Mullah’s wives. The guards all died in the defence of the women whose screams and shouts almost drowned out the rifle shots.

As the forces closed in on Tale they learned of tribal leaders deserting the Mullah. One defector was one of the Mullah’s many sons who approached the force and told them exactly where his father was, warning that he was about to move on soon.

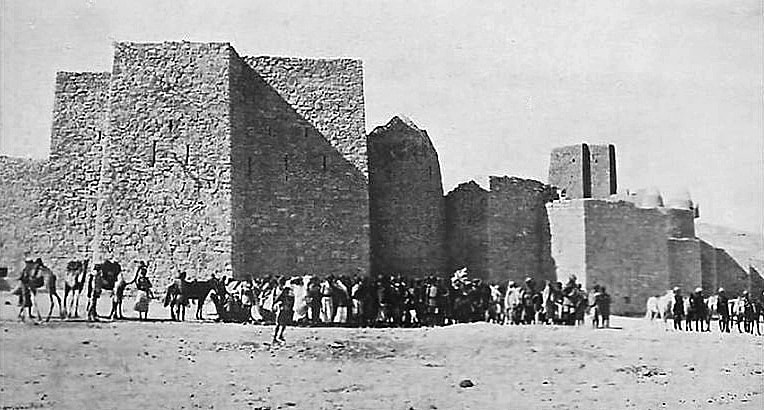

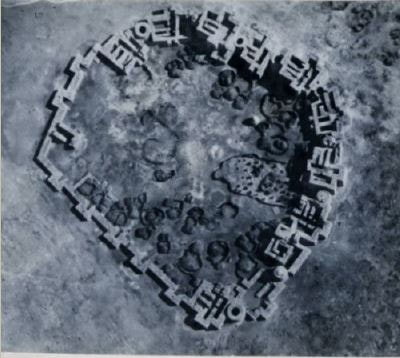

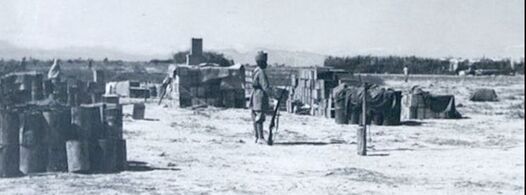

The complex of forts at Tale

Very little had been known of the Tale forts until the photographs taken by the RAF revealed how extensive they were. The Nine-Acks began bombing them, using mostly 20 lbs Cooper bombs with a few 112 lbs HE bombs for good measure. Incendiaries on the huts caused fires, fanned by the strong wind. The scattered groups of Dervishes reaching Tale to join with the Mullah found that he was intending to escape to the south west. They made no attempt to occupy the forts.

A group of tribal levies reached Tale just as darkness was falling and camped for the night. Their sudden dawn attack scattered the Dervishes and the undefended forts were quickly captured.

Next day, the levies cornered another fleeing group and killed all the men. Among the captives was the Mullah’s favourite wife. It seemed that the campaign was over and the Mullah driven into exile. Many of the levies were particularly pleased that the fighting was over. Someone had to take care of the 1400 camels, 450 cows and 50 ponies which had been captured from the dervishes.

There was considerable relief that the forts were taken without fighting. All were stoutly built and some were very large. In the picture the men and animals give scale to the most impressive.

Next day, the levies cornered another fleeing group and killed all the men. Among the captives was the Mullah’s favourite wife. It seemed that the campaign was over and the Mullah driven into exile. Many of the levies were particularly pleased that the fighting was over. Someone had to take care of the 1400 camels, 450 cows and 50 ponies which had been captured from the dervishes.

There was considerable relief that the forts were taken without fighting. All were stoutly built and some were very large. In the picture the men and animals give scale to the most impressive.

(If you dip into Google Earth and take a tour of Somalia you will appreciate how tough this campaign was. Find Tale and click on the accompanying photograph. This very fort is still there, now in colour of course and kept as an attraction to be visited by any tourist who chooses to ‘go somewhere different’).

On 18 February, their job done, the Nine-Acks flew back to Berbera. It was less than a month since they had first flown into action and they had suffered no casualty. They could scarcely claim that they had won the war – their bombs caused no serious material damage. But their mere presence had demoralised the enemy and their overview gave the ground forces vital information which allowed them to operate effectively.

Official reports of the campaign took a balanced view of each service’s contribution but could not help concluding that the RAF’s range of operation and flexibility had been the vital factor in the success of the expedition compared with the previous four failures. This, and the fact that the whole affair had cost just £83,000, were the main planks in the argument of Trenchard and Churchill, then Colonial Secretary, that the RAF should take over the Air Policing of Iraq. The plan was finally agreed in August 1921.

On 18 February, their job done, the Nine-Acks flew back to Berbera. It was less than a month since they had first flown into action and they had suffered no casualty. They could scarcely claim that they had won the war – their bombs caused no serious material damage. But their mere presence had demoralised the enemy and their overview gave the ground forces vital information which allowed them to operate effectively.

Official reports of the campaign took a balanced view of each service’s contribution but could not help concluding that the RAF’s range of operation and flexibility had been the vital factor in the success of the expedition compared with the previous four failures. This, and the fact that the whole affair had cost just £83,000, were the main planks in the argument of Trenchard and Churchill, then Colonial Secretary, that the RAF should take over the Air Policing of Iraq. The plan was finally agreed in August 1921.

What happened next to Mullah Hassan? He found an uneasy hiding place in Abyssinia. The Governor of British Somaliland encouraged a group of Sheiks to visit him and invite him to discussions to draw up a peace treaty. The Sheiks found him to be unreasonable, even demented and they left with nothing arranged. In November 1920, the Mullah was caught by the influenza epidemic that swept the world and he died, aged 56.

His influence lives on. He remains to this day a revered figure and his poetry is inspirational to current jihadis. If those adventurous tourists ever go to Magadishu, that’s Somali’s present capital, they can take a picture of his magnificent statue.