Airlift from Kabul (July 2020)

It all started with a trip to Europe, an extended tour of Western nations which greatly impressed King Amanullah Khan and his young queen. This was in 1928 and they returned to Afghanistan fired with determination to reform the government and the entire lifestyle of the nation. With so much to do, Amanullah rejected step by step changes and leapt immediately to the end goal.

At a 4-day conference – more a lecture - he announced that he would set up a Parliament – a first for the country – to be elected by all literate Afghans. Polygamy and purdah for all females would be abolished and there would be education for women and girls. European dress would be worn, top hats and tails for palace attendants, even short skirts and bobbed hair for women.

All this horrified the majority of his conservative Muslim subjects and almost immediately there were pockets of open rebellion.

One fanatical tribe attacked and plundered the royal palace at Jallalabad. Others cut the water supply to Kabul, blew up bridges and blocked the road to Peshawar over the Khyber Pass. The King’s response was to launch the venerable DH-9 bombers of the Afghan Air Force. That they were flown by ‘infidel’ White Russian pilots added fuel to the fire of the rebellion.

At a 4-day conference – more a lecture - he announced that he would set up a Parliament – a first for the country – to be elected by all literate Afghans. Polygamy and purdah for all females would be abolished and there would be education for women and girls. European dress would be worn, top hats and tails for palace attendants, even short skirts and bobbed hair for women.

All this horrified the majority of his conservative Muslim subjects and almost immediately there were pockets of open rebellion.

One fanatical tribe attacked and plundered the royal palace at Jallalabad. Others cut the water supply to Kabul, blew up bridges and blocked the road to Peshawar over the Khyber Pass. The King’s response was to launch the venerable DH-9 bombers of the Afghan Air Force. That they were flown by ‘infidel’ White Russian pilots added fuel to the fire of the rebellion.

The scattered elements of the arising coalesced around the charismatic Bacha-i-Saqao, a sort of Robin Hood figure who came from the north with some 3,000 tribesmen. They rapidly overcame the token resistance offered by the royal army and approached Kabul. In the process they captured a couple of old Turkish forts on either side of the compound of the British Legation. Soon the ‘front line’ settled there. The indiscriminate rifle fire caused some damage to the buildings. Whilst the women and children crouched under the billiard table, the Minister, Sir Francis Humphrys bravely stood at the gates and was able to confront Bacha-i-Saqao directly.

The ambassador was assured that there was no dispute with the foreigners and no one would be harmed. This might have seemed reassuring but Humphrys was aware that the situation could quickly get out of hand and he should prepare for the possible evacuation of the Legation staff.

If the Khyber Pass remained closed the only way out of Afghanistan was by air. As an ex-RAF pilot, HE already had good relations with AVM Sir Geoffrey Salmond, the RAF Commander in India. The normal means of communication via the city’s wireless station had broken down. Providentially Sir Francis had a small radio set he had bought on a whim during his last visit to London. He was able to contact the RAF in India and asked for, initially, an airmail service and also planning for a possible evacuation by air.

Although it was nearly 90 years before, in everyone’s mind was the disastrous attempted evacuation of a British force from Kabul in 1842. 4,500 troops and 12,000 civilians tried to escape through winter snows and hostile tribesmen via the Khyber Pass. Only one European and a few Indian sepoys reached safety. Everyone else was killed.

Salmon’s resources were limited. He had 24 DH9As which were usual for ‘aerial policing’, two recently arrived Wapitis which were there for operational trials and a HP Hinaidi transport. This was away in Baghdad on its way home from a trip to Egypt.

Just 10 days before, a single Victoria transport had arrived for high altitude tests and had already being stripped of unnecessary equipment. Salmond sent a signal asking for the 10 Victorias of 70 Sqn, normally based in Iraq, to be sent to India, a 2,800 mile journey with frequent stops for refuelling.

The signal for help had been received on the afternoon of 17 December. The next morning, Salmond sent Fg Off Trusk in his DH9A on a reconnaissance flight to Kabul. Trusk took LAC Donaldson as wireless operator and a Popham Panel to be dropped at the Legation. This is a white panel covered with green painted slats like a Venetian blind. Opening the slats revealed the white so it could be used to transmit Morse code messages.

In Kabul Lady Humphrys had anticipated the need to send signals to any aircraft and had organised the ladies to cut up sheets into strips. They set out a message on the lawn. It read DO NOT LAND FLY HIGH ALL WELL. When Trusk arrived he saw the message and the Union Jack on the flagpole but there was no sign of life. So he came down low to drop the panel. He was unaware of the position of the rebels around the location. Naturally, they couldn’t resist firing at the aeroplane – it could have been one of the Russians. Suddenly, Trusk was covered in oil. He climbed away trying to get height before the engine seized and Donaldson tapped out a message ‘Been hit. Radiator burst. Landing Sherpur.’

In Kabul Lady Humphrys had anticipated the need to send signals to any aircraft and had organised the ladies to cut up sheets into strips. They set out a message on the lawn. It read DO NOT LAND FLY HIGH ALL WELL. When Trusk arrived he saw the message and the Union Jack on the flagpole but there was no sign of life. So he came down low to drop the panel. He was unaware of the position of the rebels around the location. Naturally, they couldn’t resist firing at the aeroplane – it could have been one of the Russians. Suddenly, Trusk was covered in oil. He climbed away trying to get height before the engine seized and Donaldson tapped out a message ‘Been hit. Radiator burst. Landing Sherpur.’

Although the airfield was still occupied by the Afghan Air Force Trusk and Donaldson were roughly handled and arrested as spies. They were dragged into the office of the Commander, a huge man wearing a balaclava and a bandolier. He greeted the crew and offered them lunch. Just then a Russian pilot came in and asked for a bomb. The Commander took a 20lb Cooper bomb from a safe and the Russian took it away in a suitcase. The RAF men were staggered by the poor condition of the Afghan aeroplanes, unrepaired damage, holes in the panel where instruments were missing.

They were taken to a nearby hotel and given a room. The door was locked and guarded. During the night, the rebels broke in, shot the sentry and ransacked the hotel. Fortunately, they didn’t step over the sentry’s body and go into the room. It was four days before they were collected by Sir Francis’s bearer. He advised them to wear their jackets inside out so they didn’t look like the Russians and partly by car, partly by walking they reached the Legation. Even so they had to run in through a scattering of fire. They fell in through the French doors to the applause of several children and their governess.

Donaldson had brought some of the radio equipment from the Nine-Ack and when it was dark he climbed the flagpole – still under fire – to fix the aerial. Using the battery from Humphrys’ Rolls Royce he set up a more reliable communications link with Peshawar although all signals were partially blocked by the hill close behind the Legation. A Squadron Leader on the Legation staff had previously trained as an air gunner and occasionally helped on the radio. He was grateful that someone in Peshawar had the good sense to use an operator who transmitted at only 8 words per minute and not the usual 20+ wpm.

Whilst Trusk and Donaldson were marooned at the airfield the fighting around the Legation had raged back and forth. The rebels had captured some guns and now casually aimed shells from both sides were striking the compound causing damage to many of the buildings. Whilst the rebels knew that the occupants of the Legation were non-combatant foreigners the Afghan army suspected the building could have taken over by the rebels so they shot at any head that popped up.

Lady Humphrys took control indoors moving stores and food to upstairs rooms in case the outside storehouses were looted. Medical supplies and bandages were prepared and baths were filled with water for use if the normal supply were to be interrupted. The main dining room with its large windows was badly damaged and eating was moved to a smaller room on the less vulnerable side of the building. (The situation was echoed, if exaggerated, in the film ‘Carry On Up the Khyber’ when Sid James laughed off the falling plaster and shattering glass). As well as damage from small arms, 59 shells landed on the building, many more in the compound. Two Afghan servants were shot and killed and another wounded.

The ambassador meanwhile was trying to negotiate with both the King’s forces and the rebels to use the airfield safely. Sometimes the negotiations were at the point of a gun. When a small troop of the army broke in through the main gates they were met by the ambassador who calmly persuaded them to leave. He thought it helped to demonstrate non-aggression by casually smoking his pipe. He maintained this dignified and dangerous stance throughout the siege.

The RAF continued to send reconnaissance DH9As to assess the situation and read any signs on the lawn. In the Legation were two Germans who were first seen hiding in a ditch, waving a German flag tied to a walking stick. They were ushered in for safety. After a few days, in a lull in the fighting they were able to go back to their own Legation which was on the other side of the city and not under any kind of siege. Some of the Germans were able to get away in a Junkers F.13 which the King had bought during his European tour.

Donaldson had brought some of the radio equipment from the Nine-Ack and when it was dark he climbed the flagpole – still under fire – to fix the aerial. Using the battery from Humphrys’ Rolls Royce he set up a more reliable communications link with Peshawar although all signals were partially blocked by the hill close behind the Legation. A Squadron Leader on the Legation staff had previously trained as an air gunner and occasionally helped on the radio. He was grateful that someone in Peshawar had the good sense to use an operator who transmitted at only 8 words per minute and not the usual 20+ wpm.

Whilst Trusk and Donaldson were marooned at the airfield the fighting around the Legation had raged back and forth. The rebels had captured some guns and now casually aimed shells from both sides were striking the compound causing damage to many of the buildings. Whilst the rebels knew that the occupants of the Legation were non-combatant foreigners the Afghan army suspected the building could have taken over by the rebels so they shot at any head that popped up.

Lady Humphrys took control indoors moving stores and food to upstairs rooms in case the outside storehouses were looted. Medical supplies and bandages were prepared and baths were filled with water for use if the normal supply were to be interrupted. The main dining room with its large windows was badly damaged and eating was moved to a smaller room on the less vulnerable side of the building. (The situation was echoed, if exaggerated, in the film ‘Carry On Up the Khyber’ when Sid James laughed off the falling plaster and shattering glass). As well as damage from small arms, 59 shells landed on the building, many more in the compound. Two Afghan servants were shot and killed and another wounded.

The ambassador meanwhile was trying to negotiate with both the King’s forces and the rebels to use the airfield safely. Sometimes the negotiations were at the point of a gun. When a small troop of the army broke in through the main gates they were met by the ambassador who calmly persuaded them to leave. He thought it helped to demonstrate non-aggression by casually smoking his pipe. He maintained this dignified and dangerous stance throughout the siege.

The RAF continued to send reconnaissance DH9As to assess the situation and read any signs on the lawn. In the Legation were two Germans who were first seen hiding in a ditch, waving a German flag tied to a walking stick. They were ushered in for safety. After a few days, in a lull in the fighting they were able to go back to their own Legation which was on the other side of the city and not under any kind of siege. Some of the Germans were able to get away in a Junkers F.13 which the King had bought during his European tour.

Sir Francis decided it was time to call in the RAF. He made contact with an official from the Afghan Foreign Ministry who brought a letter from the King, effectively apologizing for the damage to the Legation caused by the Afghan forces and agreeing that the ladies could leave from the airfield in ‘the big aeroplane’. Donaldson tapped out a message on the evening of 22 December and overnight preparations were made in Risalpur, the RAF airfield near Peshawar. The following morning a Wapiti took off intending to be first to land at Sherpur to ensure that all was clear. Following it was a Victoria for the evacuees, flown by Sqn Ldr Reginald Maxwell of 70 Squadron and three DH9As to take baggage.

In Kabul at 5.30 am a small group of women and children left the British Legation, escorted by a few Afghan soldiers. They picked their way through the battle lines. For over an hour they avoided damaged buildings and dead bodies until at last they reached the Italian Legation. There they met other women and children from other legations, none of which had been so closely bound up in the shooting war as the British. When the time was right, they were taken by car to the airfield to meet the Victoria which landed at 9.30 a.m. The engines were kept running as the passengers climbed aboard.

In Kabul at 5.30 am a small group of women and children left the British Legation, escorted by a few Afghan soldiers. They picked their way through the battle lines. For over an hour they avoided damaged buildings and dead bodies until at last they reached the Italian Legation. There they met other women and children from other legations, none of which had been so closely bound up in the shooting war as the British. When the time was right, they were taken by car to the airfield to meet the Victoria which landed at 9.30 a.m. The engines were kept running as the passengers climbed aboard.

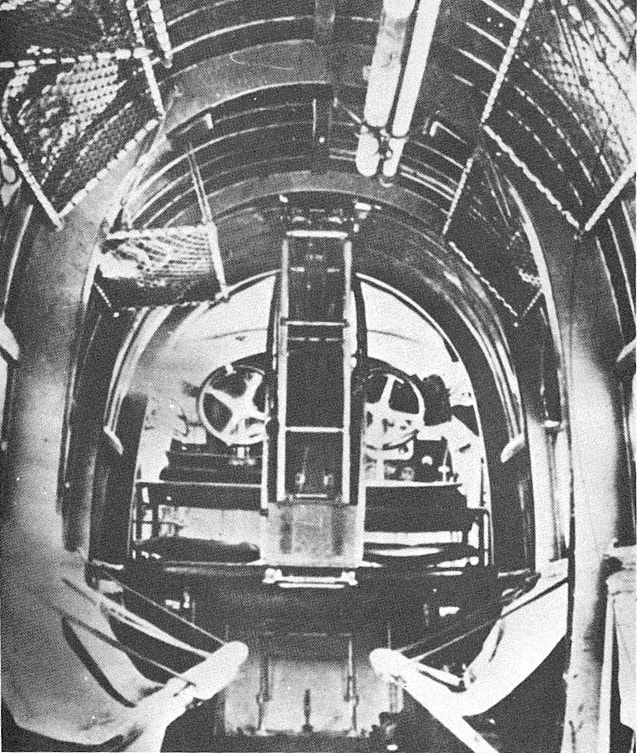

Maxwell had estimated that he could comfortably take 10 passengers. 23 climbed aboard. Some found it difficult to squeeze through the door. Everybody seemed to be wearing at least three coats to counter the bitter winter weather. The Victoria left the ground at 9.45, closely followed by the single engine biplanes. The aircraft climbed high in the turbulent air to fly between the mountains, the passengers experiencing a mixture of emotions – relief, fright (few had flown before), cold, of course, then airsickness. The crew passed canvas buckets round, emptying them regularly over the side. All unpleasantness faded when two hours later they landed at Risalpur, near Peshawar. The first evacuation had gone without a hitch.

Left on the ground at Sherpur was Sgt Peters of the Royal Corps of Signals. He had come on one of the DH9As bringing a powerful short wave radio set. This was installed in the Legation and gave more reliable contact with Peshawar than Donaldson’s long wave set. It was used to organise another evacuation flight the next day, the 24th December. The Victoria came back, this time with no fewer than eleven Nine-Acks. They took away 16 German women and children, 10 French, one Swiss and one Romanian. There was no flight on Christmas day and, curiously, almost no fighting. Bacha-i-Saqao had been wounded in the shoulder and gone away for treatment. At the same time his fighters had regrouped to attack the city from a different direction.

Left on the ground at Sherpur was Sgt Peters of the Royal Corps of Signals. He had come on one of the DH9As bringing a powerful short wave radio set. This was installed in the Legation and gave more reliable contact with Peshawar than Donaldson’s long wave set. It was used to organise another evacuation flight the next day, the 24th December. The Victoria came back, this time with no fewer than eleven Nine-Acks. They took away 16 German women and children, 10 French, one Swiss and one Romanian. There was no flight on Christmas day and, curiously, almost no fighting. Bacha-i-Saqao had been wounded in the shoulder and gone away for treatment. At the same time his fighters had regrouped to attack the city from a different direction.

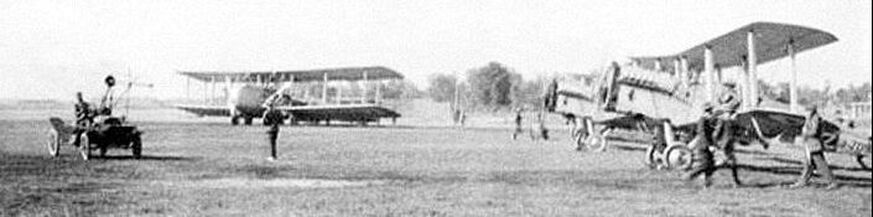

The airfield at Kabul with one Victoria, two Nine-Acks and a Hucks starter.

The airfield at Kabul with one Victoria, two Nine-Acks and a Hucks starter.

26th December – The Victoria and four Nine-Acks evacuated 23 women and children. In the noise and confusion of the running engines a German women was struck by a Nine-Ack’s propeller. She apparently recovered and was evacuated on a later flight. The prop didn’t recover and was replaced by the one from Trusk’s DH9A.

27th and 28th December – Heavy snowfall stopped all flying.

27th and 28th December – Heavy snowfall stopped all flying.

These Hinaidi passengers,

for whatever reason,

refused the offer of RAF blankets.

These Hinaidi passengers,

for whatever reason,

refused the offer of RAF blankets.

29th December– Sir Francis rounded up combatants from both sides (!) to clear the snow from a runway. The Victoria took 23 passengers and was now joined by the Hinaidi. Another 31 Italians, Indians, Germans, Turks and Syrians duly left in the Hinaidi and the Nine-Acks. By now, baggage limits were being imposed, 20lbs per adult, 15lbs per child.

30th December – Two Victorias brought out 22 women and children.

1st January– One Victoria brought out 1 German and 5 Turkish women and Fg Off. Trusk’s DH9A, repaired, was flown home.

30th December – Two Victorias brought out 22 women and children.

1st January– One Victoria brought out 1 German and 5 Turkish women and Fg Off. Trusk’s DH9A, repaired, was flown home.

The Hinaida had its own adventures. At the beginning of the affair it had been in Hinaidi – that’s the airfield near Baghdad. Following his orders to get home to Peshawar a.s.a.p. the pilot, Flt Lt Anderson, left at dawn. Just three hours into the flight one of the engines ‘died’. He had to land in the desert. Luckily, he was only 10 miles from a refinery of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. They sent a truck to help. They decided it was easier to take the aeroplane to the tools for repair. The tail was lifted and lashed down to the back of the truck. The Hinaidi was then trundled, tail first, at snail’s pace all the way to the refinery’s workshop. It took some time to repair the Jupiter engine – it had ‘swallowed one of its own exhaust valves’. Anderson resumed his journey, spending 12 hours in the air on Christmas Day. After its rescue flight from Kabul on 29th it was felt that it really did need new engines. It was taken away to have two new Jupiters fitted.

With all the women and children from the various Legations evacuated the Victorias continued to provide a regular service carrying mail and stores. Depending on the fortunes of war and rebellion there was always the chance that the male diplomatic staff and the many non-diplomatic non-Afghanis in Kabul would want to be evacuated. The rebellion was gaining strength, although there was also some in-fighting between rival factions.

Then, very early in the morning of 14th January, a convoy of seven cars left the Royal Palace and sped off towards Kandahar. King Amanullah had abdicated and retreated to his home town.

He had nominated his older brother, Inayatullah, to succeed him. Independently, Bacha-i-Saqao proclaimed himself Amir (and assumed the title of Amir Habibullah Khan). The new king decided to send a delegation to Bacha-i-Saqao proposing peace talks. This action took place right outside the British Legation and was watched by Sir Francis and described by LAC Donaldson in his signals.

They saw a Model T Ford crammed with half a dozen people waving a white flag. The rebels fired at them and they turned back. Swarming after them some rebels climbed the wall into the Legation grounds. Sir Francis, quite alone, walked out and berated them. Of course, they didn’t understand a word and luckily Bacha-i-Saqao turned up on a white horse. He also knew no English but had with him a cousin who spoke a kind of pidgin English, enough to get their promise, for the second time, to respect the Union Jack and leave the Legation grounds.

The King was holed up in an almost impregnable fortress with 5,000 troops and enough supplies to hold out for a year. Outside was a huge force of 16,000 rebels occupying the city and the airfield. And then there was, beyond the city, another amorphous group of tribes, loyal to no-one and hoping for a looting opportunity.

With all the women and children from the various Legations evacuated the Victorias continued to provide a regular service carrying mail and stores. Depending on the fortunes of war and rebellion there was always the chance that the male diplomatic staff and the many non-diplomatic non-Afghanis in Kabul would want to be evacuated. The rebellion was gaining strength, although there was also some in-fighting between rival factions.

Then, very early in the morning of 14th January, a convoy of seven cars left the Royal Palace and sped off towards Kandahar. King Amanullah had abdicated and retreated to his home town.

He had nominated his older brother, Inayatullah, to succeed him. Independently, Bacha-i-Saqao proclaimed himself Amir (and assumed the title of Amir Habibullah Khan). The new king decided to send a delegation to Bacha-i-Saqao proposing peace talks. This action took place right outside the British Legation and was watched by Sir Francis and described by LAC Donaldson in his signals.

They saw a Model T Ford crammed with half a dozen people waving a white flag. The rebels fired at them and they turned back. Swarming after them some rebels climbed the wall into the Legation grounds. Sir Francis, quite alone, walked out and berated them. Of course, they didn’t understand a word and luckily Bacha-i-Saqao turned up on a white horse. He also knew no English but had with him a cousin who spoke a kind of pidgin English, enough to get their promise, for the second time, to respect the Union Jack and leave the Legation grounds.

The King was holed up in an almost impregnable fortress with 5,000 troops and enough supplies to hold out for a year. Outside was a huge force of 16,000 rebels occupying the city and the airfield. And then there was, beyond the city, another amorphous group of tribes, loyal to no-one and hoping for a looting opportunity.

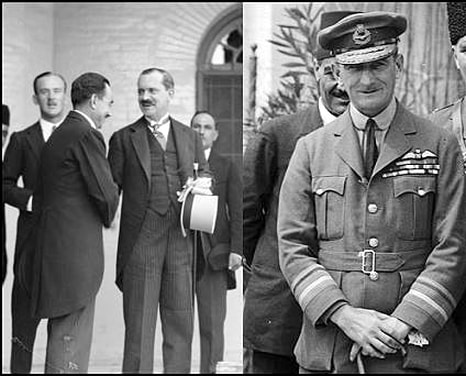

Inayatullah at Risalpur

Inayatullah at Risalpur

In response to an ultimatum Inayatullah, who had never really wanted to be king anyway, said he would surrender only if he, his family and his ladies plus any of his officials who opted for it were given safe passage out of the country on a British aeroplane. A written agreement was drawn up in which the king said that, ‘when he was seated in the aeroplane and it had started to fly’ he would hand over to Habibullah Khan (that’s Bacha-i-Saqao). When this was signed, Sir Francis sent a signal sent to India.

Thus it was that on 18th and 19th January two Victorias, flown by Sqn Ldr Maxwell and Flt Lt Ronald Ivelaw-Chapman took the king of three days and his entourage out of Afghanistan.

Thus it was that on 18th and 19th January two Victorias, flown by Sqn Ldr Maxwell and Flt Lt Ronald Ivelaw-Chapman took the king of three days and his entourage out of Afghanistan.

Habibullah Khan occupied the Palace and hunted down ministers and officials of Amanullah’s (that’s the last king but one) government. With only a little light torture he encouraged them to hand over their accumulated wealth. He cancelled any ‘reforms’ initiated by Amanullah, closed the schools run by the French and Germans and recruited troops for his army from tribes he could trust. Disorderly rabbles were cleared from the city and any looters publicly shot.

Habibullah might have consolidated his position in Kabul but there was little sign that he was accepted by the rest of the country. Other candidates emerged and an election campaign by tribal warfare broke out. Even Amanullah thought he would rescind his abdication. Everyone expected that ’when the snow melts’ there would be general warfare.

The remaining occupants of the foreign legations deemed it would be sensible to follow their womenfolk until some semblance of stability was restored. With the Khyber Pass still firmly closed, there was only one way out. And only one man to organise the evacuation. Sir Francis had to maintain his neutral/non-aggressive diplomatic relations with the new king so that his re-organised army/ex-rebels who controlled the airfield would allow the Victorias to land without shooting at them.

This second stage of the evacuation had hardly got under way when there was a moment of alarm. On 29th January a Victoria set off for Kabul and failed to arrive. Late the next day a message filtered through to Sir Francis. It said simply that the Victoria was ‘down near Saroli’.

Habibullah might have consolidated his position in Kabul but there was little sign that he was accepted by the rest of the country. Other candidates emerged and an election campaign by tribal warfare broke out. Even Amanullah thought he would rescind his abdication. Everyone expected that ’when the snow melts’ there would be general warfare.

The remaining occupants of the foreign legations deemed it would be sensible to follow their womenfolk until some semblance of stability was restored. With the Khyber Pass still firmly closed, there was only one way out. And only one man to organise the evacuation. Sir Francis had to maintain his neutral/non-aggressive diplomatic relations with the new king so that his re-organised army/ex-rebels who controlled the airfield would allow the Victorias to land without shooting at them.

This second stage of the evacuation had hardly got under way when there was a moment of alarm. On 29th January a Victoria set off for Kabul and failed to arrive. Late the next day a message filtered through to Sir Francis. It said simply that the Victoria was ‘down near Saroli’.

I-C de-whiskering

I-C de-whiskering

The Victoria had been over the mountains beyond the pass when both engines failed. The only ‘flat’ piece of land to be seen was a tiny plateau no longer than 60 yds with steep drops on three sides. The pilot, Flt Lt Ivelaw-Chapman, side slipped down and deliberately stalled the Victoria 10 feet above the ground. The undercarriage collapsed and the Victoria came to a stop without sliding. In no time they were surrounded by a shouting mob of heavily armed tribesmen. They were rescued by a character in a military greatcoat, a ‘Brigadier’, who understood enough of Chapman’s limited Urdu. They had ‘blood chits’ but were still under suspicion because of their blue Russian-like uniforms. Before they left the wreck Chapman was able to check the engines and found the fuel filters choked with ice, which had caused the engine failure.

The two airman then had an extraordinary and prolonged adventure when they were passed from one group and host to another, ostensibly on the way back to India. After six days, Chapman found a place long enough to clear an airstrip. A Bristol Fighter was sent and the two pilots were flown home and re-united with their razors.

The two airman then had an extraordinary and prolonged adventure when they were passed from one group and host to another, ostensibly on the way back to India. After six days, Chapman found a place long enough to clear an airstrip. A Bristol Fighter was sent and the two pilots were flown home and re-united with their razors.

The weather was now much colder and snowstorms frequent. The Victorias had to be better prepared. The fuel they used, a Benzole mixture, was different from that used by the DH9As and Wapitis. It had been in store at Risalpur for some time. Any water in the fuel would freeze so the fuel stores were carefully checked. Orders were issued that fuel had to be filtered, twice, before it was put into the aeroplanes’ tanks. At the end of a day’s flying, fuel filters were cleaned and the tanks filled fully. Before setting off for Kabul, a Victoria would carry out a test flight in which fuel was drawn from each tank in turn. On landing, all tanks would be topped up and fuel filters cleaned. All this was done in icy weather so the ground crews made their own significant contribution to the success of the operation. There was no further problem with icing.

By now the rejuvenated Hinaidi had rejoined the fleet and flew back to Kabul but in the middle of the landing run, one of the engines stopped. It couldn’t cope with the extremely low temperatures. Sir Francis came to the rescue with canvas, ducts and charcoal braziers from the Legation stores and a heating system was devised. It didn’t work very well and it needed modification several times. It wasn’t until 3rd February that the engines could be safely started.

Whenever the weather allowed three Victorias, flown by Maxwell, Ivelaw-Chapman and Fg Off Anness -plus the Hinaidi, piloted by Anderson - shuttled between Risalpur and Kabul. In Kabul Sir Francis continued with his delicate diplomacy and organised the passenger loads, the number of requests for evacuation increasing as inter-tribal fighting flared up from time to time. Finding people to clear snow, at times up to seventeen inches deep, was a constant task. Meanwhile, another stalwart, LAC Donaldson, assisted by Sgt Peters, coped with the vital flow of signals.

There was one other airman who came unwittingly to prominence. Although not directly involved with the airlift, his tale must be told. C Flight of 27 Sqn was based at Miranshar, a small isolated airfield some way from Risalpur. The Flight Commander’s clerk was remarkably efficient. For instance, he would present any correspondence or signal to his boss with the reply already typed for signature. He enjoyed his life with ‘the other ranks’, spending his spare time translating ancient Greek texts for a contact at Oxford University. He was Aircraftman Shaw, previously Col T E Lawrence.

The situation in Afghanistan was being closely followed in Britain, by the Government, in Parliament and in the newspapers. Somehow, one of the papers found out about Shaw/Lawrence and printed an article claiming that he had disguised himself as a ‘holy man’ and was interfering in the rebellion in Afghanistan. This filtered through to Kabul and caused some embarrassment for Sir Francis. A decision was made by Sir Hugh Trenchard, no less, that Lawrence should be brought home to England, an outcome that was regretted by all.

By now the rejuvenated Hinaidi had rejoined the fleet and flew back to Kabul but in the middle of the landing run, one of the engines stopped. It couldn’t cope with the extremely low temperatures. Sir Francis came to the rescue with canvas, ducts and charcoal braziers from the Legation stores and a heating system was devised. It didn’t work very well and it needed modification several times. It wasn’t until 3rd February that the engines could be safely started.

Whenever the weather allowed three Victorias, flown by Maxwell, Ivelaw-Chapman and Fg Off Anness -plus the Hinaidi, piloted by Anderson - shuttled between Risalpur and Kabul. In Kabul Sir Francis continued with his delicate diplomacy and organised the passenger loads, the number of requests for evacuation increasing as inter-tribal fighting flared up from time to time. Finding people to clear snow, at times up to seventeen inches deep, was a constant task. Meanwhile, another stalwart, LAC Donaldson, assisted by Sgt Peters, coped with the vital flow of signals.

There was one other airman who came unwittingly to prominence. Although not directly involved with the airlift, his tale must be told. C Flight of 27 Sqn was based at Miranshar, a small isolated airfield some way from Risalpur. The Flight Commander’s clerk was remarkably efficient. For instance, he would present any correspondence or signal to his boss with the reply already typed for signature. He enjoyed his life with ‘the other ranks’, spending his spare time translating ancient Greek texts for a contact at Oxford University. He was Aircraftman Shaw, previously Col T E Lawrence.

The situation in Afghanistan was being closely followed in Britain, by the Government, in Parliament and in the newspapers. Somehow, one of the papers found out about Shaw/Lawrence and printed an article claiming that he had disguised himself as a ‘holy man’ and was interfering in the rebellion in Afghanistan. This filtered through to Kabul and caused some embarrassment for Sir Francis. A decision was made by Sir Hugh Trenchard, no less, that Lawrence should be brought home to England, an outcome that was regretted by all.

The airlift went on through February, right until 25th when the Victorias flew over the British Legation and landed at Sherpur for the final lift. In the last Victoria to leave were Fg Off Trusk, LAC Donaldson, Sgt Peters and, clutching the Union Jack which had flown constantly from the Legation’s flagpole, Sir Francis Humphrys.

A total of 586 had been evacuated, 268 men, 153 women and 165 children. That’s 23 British, 344 British Indian, 58 Turks, 58 German and smaller numbers of Afghan, French, Italian, Syrian and 1 each Australian, American, Swiss and Romanian.

Several celebration events ensued, including a formation flypast over Delhi of all available Victorias.

A total of 586 had been evacuated, 268 men, 153 women and 165 children. That’s 23 British, 344 British Indian, 58 Turks, 58 German and smaller numbers of Afghan, French, Italian, Syrian and 1 each Australian, American, Swiss and Romanian.

Several celebration events ensued, including a formation flypast over Delhi of all available Victorias.

Sir Francis ( holding topper) back in his

working clothes at Peshawar. On the

right AVM Sir Geoffrey Salmond.

Sir Francis ( holding topper) back in his

working clothes at Peshawar. On the

right AVM Sir Geoffrey Salmond.

The Air Force Cross was awarded to the 70 Sqn pilots of the three Victorias, to the Hinaidi pilot Flt Lt Anderson and to Fg Off Trusk. LAC Donaldson deservedly was awarded the Air Force Medal. In the summer Sir Francis and his wife knelt side by side before the King. Sir Francis was awarded the KCMG and Lady Humphrys became a Dame of the British Empire.

There were many people feeling pleased at the end of February 1929. All of the evacuees, of course, the aircrew who had flown so well in such difficult conditions, the ground crew who had worked so hard and the back-up staff who had planned and provided efficiently.

The greatest glow of satisfaction, without doubt, surrounded Marshal of the RAF, Sir Hugh Trenchard. He had fought so hard for the very survival of the RAF and lived with a continuous barrage of threatening criticism. He’d even been denied the right to resign and hand over to someone else to carry on the fight. Now, in the eyes of the world and with the gratitude of many nations his service had carried out a successful operation which neither of the other more senior services had any hope of achieving. (And, to the Government’s great satisfaction, he had done it cheaply).

The greatest glow of satisfaction, without doubt, surrounded Marshal of the RAF, Sir Hugh Trenchard. He had fought so hard for the very survival of the RAF and lived with a continuous barrage of threatening criticism. He’d even been denied the right to resign and hand over to someone else to carry on the fight. Now, in the eyes of the world and with the gratitude of many nations his service had carried out a successful operation which neither of the other more senior services had any hope of achieving. (And, to the Government’s great satisfaction, he had done it cheaply).