Fokker Goes Gliding

(Aug 2020)

Things were a bit flat in the post war Fokker factory – that’s post WWI, of course. Nobody wanted any of the excellent aeroplanes they had been producing. Well, they did want all the D.VII models they could find, but only to destroy them, as the Versailles Treaty decreed.. Anthony Fokker and his small staff had plenty of time to think of new designs and go looking for customers. Although there wasn’t much aviation going on.

Then, in 1920, there was a little glimmer. A brave magazine called Flugsport (how did it find a market?) reminded its readers that the pioneer pilots had learned to fly on gliders and had even prolonged their flights by soaring in the rising air in front of wind-facing hills. The editor had discovered the Wasserkuppe, a wonderful hill in the Rhön Mountains and perfect for flying gliders. He invited enthusiasts to a meeting there, a camp in a few temporary wooden huts from 15 July to 15 September, bring your own knives and forks.

Twenty four people turned up, from Germany, Austria and Switzerland. There was a lot of talking, then some action and three weeks into the camp a delicate newly-built glider was actually launched. It managed to stay airborne for as long as 40 seconds. Three days later the wind was rather stronger and Von Lössl launched again. He sailed off in front of the hill and flew into turbulence. The tail of the glider cracked, it fell to the ground and young Von Lössl was killed. The group decided that the best way to remember their friend was to come back the following year and do better.

They did. Several gliders flew and the best flight was 3 hours and 6 minutes long. Other gliding gatherings were held in France and in 1922, a meeting was announced to be held here in England, at Itford Hill in East Sussex. Anthony Fokker decided it was worth making the effort to get involved. At this stage, it might be useful to review a little history.

Anthony Herman Gerard Fokker was born in 1890 in Indonesia, then the Dutch East Indies, where his father had a coffee plantation. The family moved to Holland when Anthony was four and he soon developed a fascination for mechanics, both steam and petrol. As he grew up he was not a diligent student and his father sent him to a Technical School in Germany to train as an automobile engineer.

In 1908 Wilbur Wright came to Europe and demonstrated his Flyer. Fokker was sufficiently inspired to change schools to one which was beginning to work on aeroplanes. He had ideas of his own and in 1910 they were incorporated in a flying machine built along with two engineers who happened to have a suitable engine. The first machine, called De Spin (The Spider) was crashed by one of the partners but the engine survived to build a second aircraft in which Fokker learned to fly – the first Dutchmen to do so. This one was also crashed by the same partner so Fokker broke away from him and a third Spin was built.

This flew well and Fokker chose a public holiday in September 1911 to demonstrate it by flying round the church tower of his local town, Haarlem. The publicity was remarkably effective. It came to the notice of the German military and within two years, Fokker had set up his own company, Fokker Aeropanbau, near Berlin, and was building aeroplanes for the German Army.

This flew well and Fokker chose a public holiday in September 1911 to demonstrate it by flying round the church tower of his local town, Haarlem. The publicity was remarkably effective. It came to the notice of the German military and within two years, Fokker had set up his own company, Fokker Aeropanbau, near Berlin, and was building aeroplanes for the German Army.

Kreutzer was replaced by Reinhold Platz who had first worked for Fokker as a welder, building all three Spin aircraft. Platz was completely untrained as a designer. All he knew he had learned when building Fokker’s aircraft. If Fokker produced an idea or outlined a shape, Platz could produce a structure of the right shape and strength.

Platz worked for Fokker from 1912 to 1931 but, in his autobiography, Fokker mentioned him only once as his ‘factory manager’. It’s widely believed that Platz should have the major credit for all Fokker’s designs after the D.I, including the famous Triplane and the world-beating D.VII.

To counter that, no-one gets any credit for the way the shop floor was run. When a new type was introduced there were often structural failures. The Dr. I Triplane killed several pilots when wings broke off during combat manoeuvres. The structure was found to be not at fault, it was just shoddily built. It’s significant that when Albatross were ordered to build a Fokker design under licence they asked for a set of drawings. Fokker sent none, just a completed aeroplane.

Platz worked for Fokker from 1912 to 1931 but, in his autobiography, Fokker mentioned him only once as his ‘factory manager’. It’s widely believed that Platz should have the major credit for all Fokker’s designs after the D.I, including the famous Triplane and the world-beating D.VII.

To counter that, no-one gets any credit for the way the shop floor was run. When a new type was introduced there were often structural failures. The Dr. I Triplane killed several pilots when wings broke off during combat manoeuvres. The structure was found to be not at fault, it was just shoddily built. It’s significant that when Albatross were ordered to build a Fokker design under licence they asked for a set of drawings. Fokker sent none, just a completed aeroplane.

Nevertheless, Fokker was a good salesman and could charm the decision makers in his major customer. His contribution to the German war effort was considerable and greatly valued. So much so he was persuaded to take German nationality in 1916 because the Germans feared he was being tempted by the Allies to work for them. When he did leave Germany it was in 1919 and he went home to the Netherlands, bringing six long train loads of aeroplanes, engines and equipment - unchecked by customs - to start a new company there.

Before leaving this period, it’s instructive to look at some of Fokker’s designs during the war.

Before leaving this period, it’s instructive to look at some of Fokker’s designs during the war.

The V. I, the first design to emerge in the Platz regime. Note the unbraced cantilever wing.

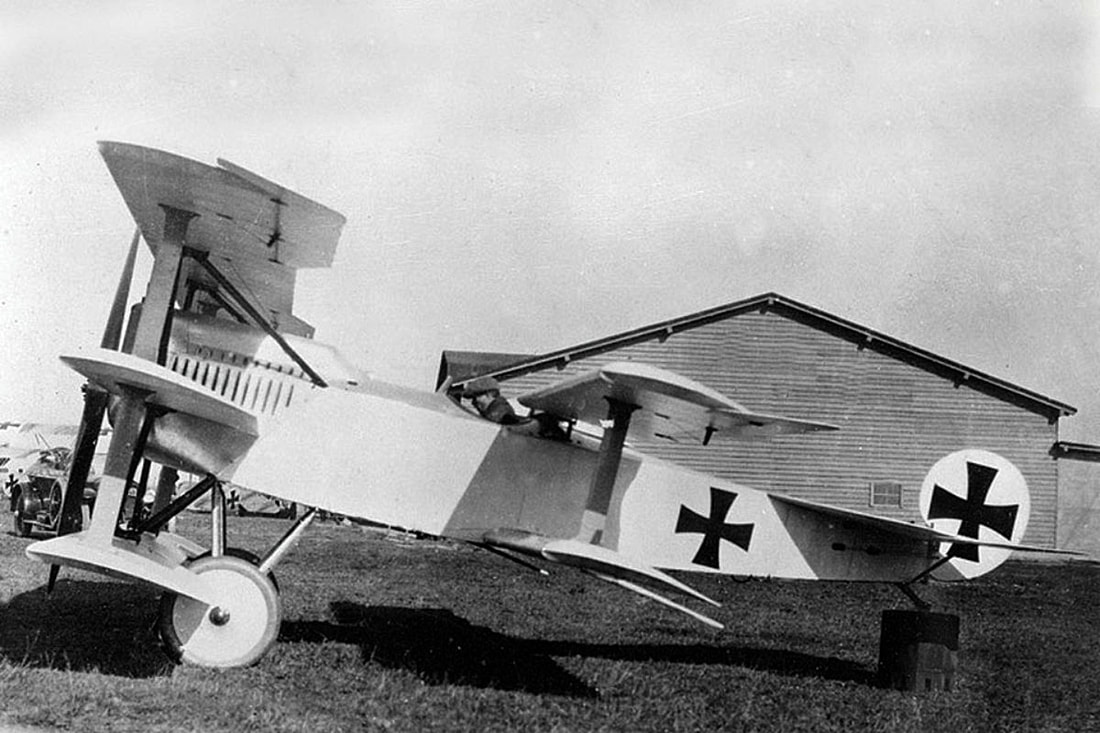

Below - left. The Dr.I, built to counter the Sopwith Triplane. (Fokker had examined a captured Sopwith Triplane and told Platz to build 'a copy' but give him no information on dimensions or structure)

Below - right If three wings were good, wouldn’t five be better. The V.8 was not ordered by the military.

The formidable D.VII The clean and efficient D.VIII

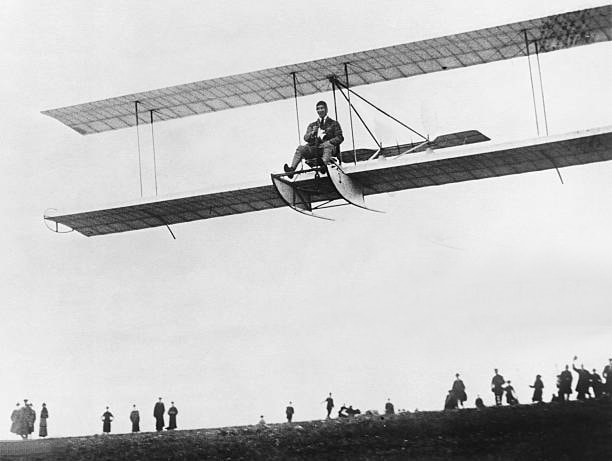

Anthony Fokker got involved in the new sport of gliding with a single-seat biplane glider. In these very early days of the sport gliders were almost always launched from the top of a hill, usually by the pilot lifting the glider and running into the wind. This was the method used by Otto Lilienthal, the original pioneer, who carried out over 2000 glides before his death in 1896. Holland is noticeably lacking in hills so test flying for Fokker was a real problem. He would have to go to the Wasserkuppe where he could use the hill and have help from the many enthusiasts there to move his big glider to the launch point and also retrieve it from the bottom of the hill.

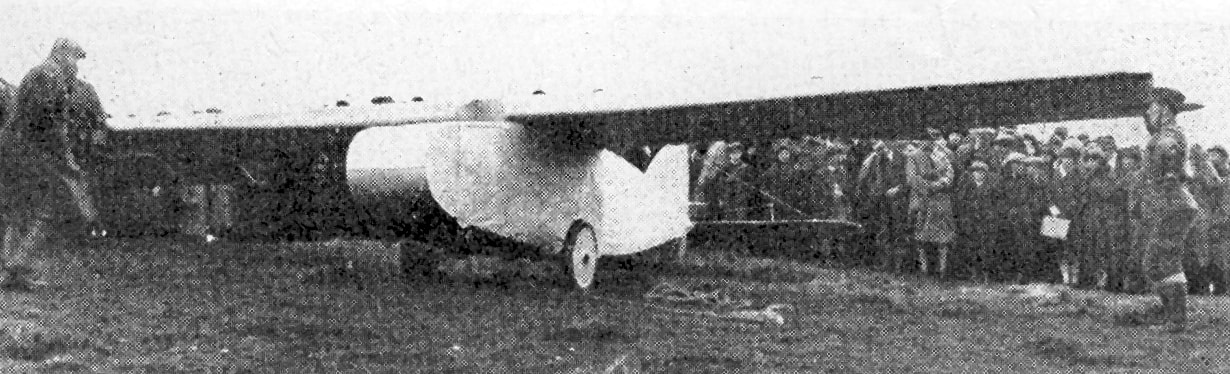

Here he is in 1921 in the FG-1 surrounded by fans and admirers.

The FG-1 flew well enough so for the 1922 meetings in England he built the FG-2. This had a second seat, on the Centre of Gravity behind the pilot, for any occasional passenger.

The FG-1 flew well enough so for the 1922 meetings in England he built the FG-2. This had a second seat, on the Centre of Gravity behind the pilot, for any occasional passenger.

These gliders were quite large and there’s no way they could be foot-launched. Fortunately, the use of elastic bungee cords was now the standard method for a 'catapult' launch and was just fine for Fokker’s glider.

The really interesting thing about this machine is the rudder(s). The rudder is particularly important in gliders. When the ailerons are used to produce roll the adverse yaw causes the nose to swing in the opposite direction. Rudder must be used to correct this. Unlike all previous Fokker designs which had a single rudder this complicated arrangement with four separate rudders emerged. It deepens the mystery of which designer – Fokker or Platz – should take the credit for this feature - or should that be blame?

The really interesting thing about this machine is the rudder(s). The rudder is particularly important in gliders. When the ailerons are used to produce roll the adverse yaw causes the nose to swing in the opposite direction. Rudder must be used to correct this. Unlike all previous Fokker designs which had a single rudder this complicated arrangement with four separate rudders emerged. It deepens the mystery of which designer – Fokker or Platz – should take the credit for this feature - or should that be blame?

It so happens that the shape of the rudders is very similar to the ones fitted to the Triplane and the D.VIII. So maybe it was just a cost-saving trick and they simply took four rudders off that train of spares. It looks as though two rudders were fitted to the single seat glider. But when they lengthened the fuselage to add the passenger seat they found they needed more directional stability and four rudders were fitted. It’s apparent that this wasn’t enough. Photographs of the FG-2 taken later in England show a small rectangular supplementary fin added untidily to the tail.

Fokker had an element of success when he flew the FG-2 at the Wasserkuppe where he scored a world’s first when he became the first pilot to fly a passenger in a glider. He moved on to the Itford Hill meeting near Lewes in Sussex, a considerable undertaking in itself to dismantle his gliders, pack and protect them for a journey by train and steamer across the Channel.

The meeting, to be held from 16-21 October, had been proposed by the Daily Mail as a publicity stunt – ‘to increase airmindedness’ they said. A prize of £1000 was offered for a glide exceeding thirty minutes duration. It attracted a wide range of competitors, the serious - manufacturers like Fokker and de Havilland, some pilots and keen individuals who were building their own machines and, of course, the lunatic fringe. There was no airworthiness or safety requirement. Balloons were prohibited but some kind of motive power was allowed provided it was produced entirely by the occupants. As well as the inevitable flying bicycle one entrant intended to bring a two-seat ‘helicopter’ in which front seat pilot drove the propeller and the rear seater drove the ‘lifting rotor’.

The weather refused to cooperate for a couple of days. A Mr Prosser, an experienced pilot, assembled his large biplane glider in one of the tented hangars then found he couldn’t get it out of the doors. It was getting late so he decided to try again in the morning. There was no problem then. It had been a wild night and the wind blew down the hangar. Sadly, it also flattened the glider.

When flying started, the gliders which were ready were launched by bungee into the wind blowing fitfully against the hill. Every glider was surrounded by crowds of spectators who were marshalled about by mounted policemen. Fokker flew with a Daily Mail reporter on board and stayed up for 7 minutes. Another glider managed 11 mins 30 secs. Then the wind picked up and Fokker launched solo. He landed 37 minutes later and the £1000 prize was his. Later in the week another pilot, Gordon Olley, flew the Fokker with a passenger and took the world two-seater record with a flight of 49 minutes.

Fokker had an element of success when he flew the FG-2 at the Wasserkuppe where he scored a world’s first when he became the first pilot to fly a passenger in a glider. He moved on to the Itford Hill meeting near Lewes in Sussex, a considerable undertaking in itself to dismantle his gliders, pack and protect them for a journey by train and steamer across the Channel.

The meeting, to be held from 16-21 October, had been proposed by the Daily Mail as a publicity stunt – ‘to increase airmindedness’ they said. A prize of £1000 was offered for a glide exceeding thirty minutes duration. It attracted a wide range of competitors, the serious - manufacturers like Fokker and de Havilland, some pilots and keen individuals who were building their own machines and, of course, the lunatic fringe. There was no airworthiness or safety requirement. Balloons were prohibited but some kind of motive power was allowed provided it was produced entirely by the occupants. As well as the inevitable flying bicycle one entrant intended to bring a two-seat ‘helicopter’ in which front seat pilot drove the propeller and the rear seater drove the ‘lifting rotor’.

The weather refused to cooperate for a couple of days. A Mr Prosser, an experienced pilot, assembled his large biplane glider in one of the tented hangars then found he couldn’t get it out of the doors. It was getting late so he decided to try again in the morning. There was no problem then. It had been a wild night and the wind blew down the hangar. Sadly, it also flattened the glider.

When flying started, the gliders which were ready were launched by bungee into the wind blowing fitfully against the hill. Every glider was surrounded by crowds of spectators who were marshalled about by mounted policemen. Fokker flew with a Daily Mail reporter on board and stayed up for 7 minutes. Another glider managed 11 mins 30 secs. Then the wind picked up and Fokker launched solo. He landed 37 minutes later and the £1000 prize was his. Later in the week another pilot, Gordon Olley, flew the Fokker with a passenger and took the world two-seater record with a flight of 49 minutes.

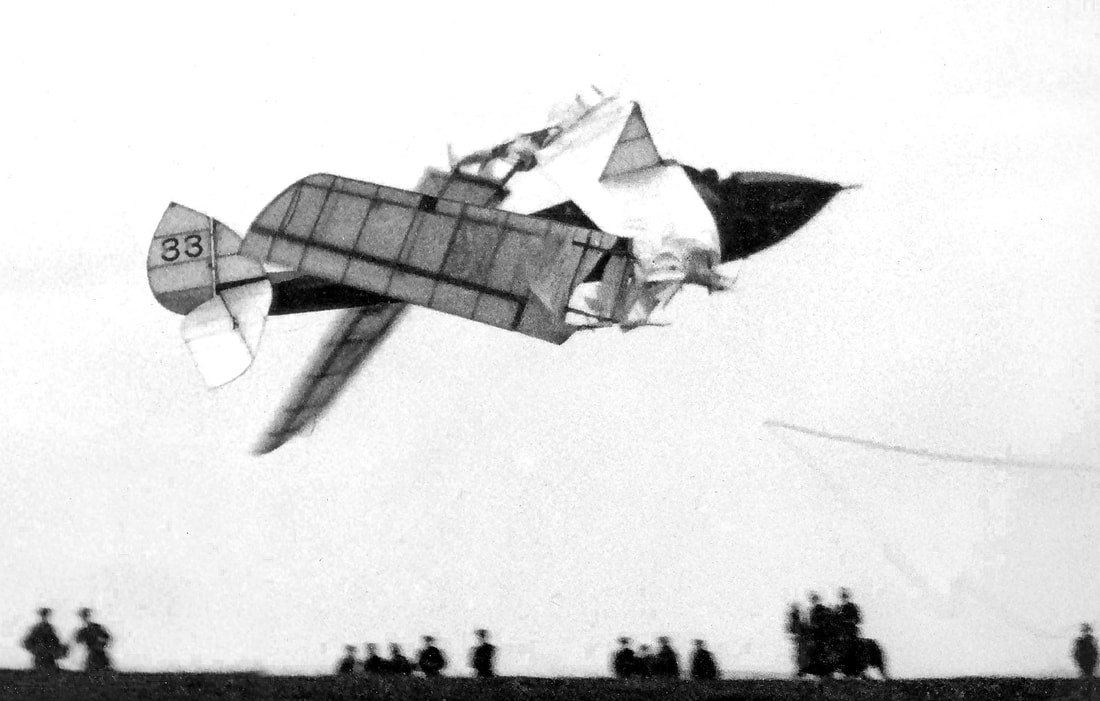

What happened to the other competitors? De Havilland brought two rather pretty gliders. The ailerons didn’t seem to be very effective so they tried locking the ailerons and re-rigging the controls to warp the wings. Luckily it was launched over fairly level ground rather than the brow of the hill and the pilot was unhurt in the crash.

M. Barbet’s Dewoitine was admired by the crowd who thought it would do well. The enthusiastic bungee launch it was given took the pilot by surprise. The Dewoitine reared up into the air, stalled, slipped onto a wing tip and rolled itself into a ball of wreckage.

It wasn’t necessarily the best-looking machines which did well.

There was another Fokker at the meeting - part of one anyway. Sqn Ldr A Gray assembled his glider at the last minute. He had bought a war surplus Fokker D.VII wing (5/-) and fitted it on the top of a Bristol Fighter fuselage (5/-). He spent a further 18/6 on fittings and dope.

A really unusual glider came from France. Designed by a M. Peyret it had two identical wings, each fitted with full-span hinged control surfaces which, by a clever mechanism, could be used for control in both roll and pitch.

On the final day of the meeting Alexis Maneyrol launched in the Peyret at 2.30 pm. A short time later, Sqn Ldr Gray launched in his 28/6 penny glider (Fokkfit – Brisker?). The wind blew steadily and they cruised up and down in front of the hill. Darkness fell and they soared on. There was a record at stake. Finally, Maneyrol was informed by car horns and flashing headlights that he had broken the world duration record, currently held by Germany. The cars outlined a landing strip and both gliders came in for perfect landings on top of the hill. Maneyrol had flown for a remarkable 3 hrs 21 minutes.

Oddly enough, despite the Daily Mail’s efforts, there was absolutely no positive reaction in Britain after the Itford Hill event. After all, the prizes and kudos had gone to Holland and France. Gliding was dismissed as ‘a case of collective folly’. It wasn’t until 1929, after the visit of the Austrian Robert Kronfeld, that the spark of gliding was re-kindled in Britain.

Back in Holland, Reinhold Platz reviewed his company’s foray into gliding. Fokker had done reasonably well - set a record, won a prize. But would anyone buy their gliders at the price they would need to charge to make a profit? After all, the only thing a pilot could do in them was to track up and down in front of a hill (thermals had yet to be discovered) and even that was only when the wind was in the right direction and at the right strength. Gliders which did soar successfully usually ended with the failed soarers in the fields at the bottom of the hill. This meant that the relatively delicate airframes had to be carried over rough country and dragged long distances by several people, not always volunteers.

No. There was no market for their gliders. There were other people who slid downhill and had much more fun. They could easily carry their skis to and from the slopes and they were much cheaper than aeroplanes.

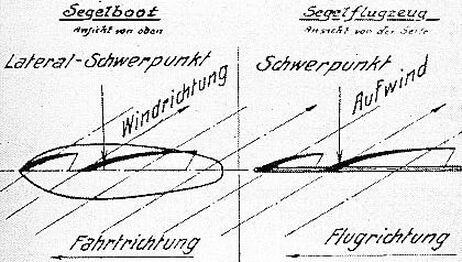

There was another wind-driven sport which Platz enjoyed, sailing. The leap from sailing to gliding was not very great. Platz could control his boat’s course without using the rudder, just by adjusting the jib. And if you looked at a sailing dinghy from above. . .

Oddly enough, despite the Daily Mail’s efforts, there was absolutely no positive reaction in Britain after the Itford Hill event. After all, the prizes and kudos had gone to Holland and France. Gliding was dismissed as ‘a case of collective folly’. It wasn’t until 1929, after the visit of the Austrian Robert Kronfeld, that the spark of gliding was re-kindled in Britain.

Back in Holland, Reinhold Platz reviewed his company’s foray into gliding. Fokker had done reasonably well - set a record, won a prize. But would anyone buy their gliders at the price they would need to charge to make a profit? After all, the only thing a pilot could do in them was to track up and down in front of a hill (thermals had yet to be discovered) and even that was only when the wind was in the right direction and at the right strength. Gliders which did soar successfully usually ended with the failed soarers in the fields at the bottom of the hill. This meant that the relatively delicate airframes had to be carried over rough country and dragged long distances by several people, not always volunteers.

No. There was no market for their gliders. There were other people who slid downhill and had much more fun. They could easily carry their skis to and from the slopes and they were much cheaper than aeroplanes.

There was another wind-driven sport which Platz enjoyed, sailing. The leap from sailing to gliding was not very great. Platz could control his boat’s course without using the rudder, just by adjusting the jib. And if you looked at a sailing dinghy from above. . .

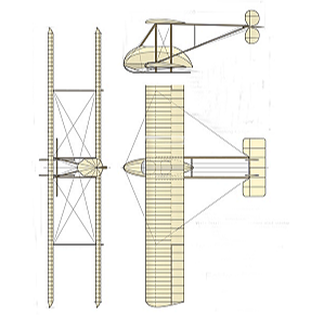

The headings on Platz’s drawing say ‘Sailboat’ and ‘Sailplane’.

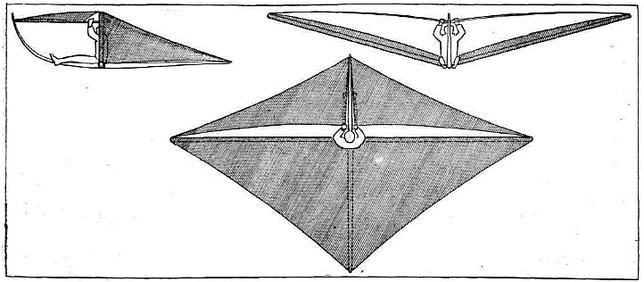

He tested the arrangement with a piece of paper and a clip. Of course it worked. Didn’t the Wright brothers use a canard - and Santos-Dumont? However, unlike those pioneering machines Platz’s canard would have flexible canvas wings, like a dinghy.

The paper model flew. A larger model, with flexible fabric wings was tested, controlled from the ground by cords attached to wing tips and keel. It was time to build the definitive glider.

He tested the arrangement with a piece of paper and a clip. Of course it worked. Didn’t the Wright brothers use a canard - and Santos-Dumont? However, unlike those pioneering machines Platz’s canard would have flexible canvas wings, like a dinghy.

The paper model flew. A larger model, with flexible fabric wings was tested, controlled from the ground by cords attached to wing tips and keel. It was time to build the definitive glider.

The keel was a steel tube and welded to it were sockets to receive the wooden main wing spars. These were fitted at a dihedral angle so that the wing tips were level with the nose of the keel where the wooden foreplane booms were attached. The wings had no ribs or battens, being made of strips of fabric sewn together with the seams in line with the airflow which determined their shape.

Only a bicycle saddle and a couple of footrests were needed and the glider was ready to fly. Platz considered fitting a rudder but thought the sharp dihedral angle would provide adequate directional stability. Control would be by varying the angle of the foreplanes - increase the angle (both hands down) to climb, both hands up to dive. To turn left, left hand up, right hand down,.

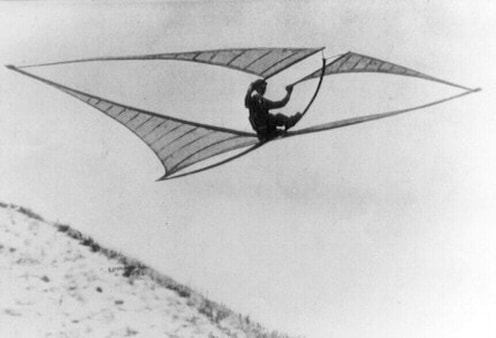

It isn’t far from the Fokker factory to the seaside resort of Vlissingen where the steep sand dunes stretch for seven miles. They face the prevailing wind and were the ideal place to test the glider. It was a chilly day in February 1923 when the first manned flights were made. They wrapped up warmly.

The glider was flown first with ballast and control lines which established the correct setting for the foreplanes. Platz had plenty of volunteers to fly his glider and it was tested by people of varying weights up to 100kg (15 st 10 lbs). They all reached the same conclusion.

The contraption certainly flew – but not very well. The pitch control (both hands moving together) produced a slight reaction but not much. The most important factor in determining the angle of glide was position of the pilot and he had to be on the C. of G. To have a moveable seat as a control was not an option.

The differential movement of the foreplanes produced no reaction at all and the glider flew straight on. This was probably because the wing surfaces were too close to the centre line, normal ailerons are always fitted at the wing tips. There were other potential problems. What if you needed to scratch your nose or got a fly in your eye?

The differential movement of the foreplanes produced no reaction at all and the glider flew straight on. This was probably because the wing surfaces were too close to the centre line, normal ailerons are always fitted at the wing tips. There were other potential problems. What if you needed to scratch your nose or got a fly in your eye?

The glider needed a fundamental redesign and Platz could see that the end result would be so far from the simplicity of the original concept that he would not achieve any of his aims. There was a little glow of satisfaction that he got close in one respect. All rolled up and packed away in ten minutes his glider weighed 40 kg - 88lbs. It could, just, be carried on a bike.

The glider faded into history and Fokker got on with the serious business of producing many successful designs, airliners, fighters, bombers - but no more gliders.

The glider faded into history and Fokker got on with the serious business of producing many successful designs, airliners, fighters, bombers - but no more gliders.

Platz’s glider was not entirely forgotten. It was such an imaginative idea that people wanted it to have worked. Articles were written about it, models were built and, although the understanding of aerodynamics had improved over the years all the replicas flew like the 1923 original.

|

Apart from . . . Kite manufacturers build all sorts of shapes and they fly like kites. Except for the Platz shape. With tension on the cord, it launches like a kite, then, if the tension is relaxed, it flies like a glider and cruises gently across the sky. Pull on the cord and it climbs for another slow descent. The Zero G is the only kite that can be flown in zero wind, even indoors. Until recently, you could buy one from Amazon. Now it’s marked ‘Out of Stock’ and it seems that Prism are no longer making them. |