Picking up the Pieces

Recovering crashed aircraft from the Zuyder Zee

With half of their land area less than one metre above sea level the Dutch have been building dykes and draining lakes for over a thousand years. The first proposal to tame the North Sea and drain the Zuider Zee emerged as long ago as 1667 but it wasn’t until 1891 that a practical plan to build a 32 km dam to seal off the Zuider Zee was produced. There was much opposition, not only on grounds of cost and disruption of the fishing industry. A disastrous flood in January 1916, when many existing dykes were broken and lives were lost, served to harden the resolution of Parliament and the necessary Act was passed.

Work began on the smaller Amsteldiepdijk to produce the first polder of drained land in 1924. The engineers then turned to the enormous Afsluitdijk. By 1932, the ZuiderZee was divided and the inner lake, the IJsselmeer, was sealed off from the sea. Dyke building and draining moved to the eastern side of the sea and the Noordoostpolder was completed in 1942. [Although the polder had been drained the land was soft mud and not yet suitable for agriculture. Any aircraft which crashed there lay on the surface. Not all the crew died in the crashes. Many had bailed out before their planes fell. Yet in the last three years of the war there were 175 burials of dead airmen recorded in this small area alone which gives an indication of how many bombers used the Zuyder Zee as a ‘flak-free’ entry to Europe.]

Gradually the Ijsselmeer changed from being a seawater inlet to a freshwater lake. Fishermen found different kinds of fish and in one area they raised particularly good catches of eels. They also caught many pieces of aluminium structure which ripped their nets.

In June 1947 the Dutch navy was called in and a diver cleared away the offending bits of the wreckage of a Wellington, including parts of a gun turret and some remains of the gunner. These were buried in a war cemetery near Nijmegen ‘Known to God, an airman, RAF’. The diver made no attempt to identify the aircraft nor did he dig out any parts of the wreck that were buried. They were no threat to fishing nets.

Gradually the Ijsselmeer changed from being a seawater inlet to a freshwater lake. Fishermen found different kinds of fish and in one area they raised particularly good catches of eels. They also caught many pieces of aluminium structure which ripped their nets.

In June 1947 the Dutch navy was called in and a diver cleared away the offending bits of the wreckage of a Wellington, including parts of a gun turret and some remains of the gunner. These were buried in a war cemetery near Nijmegen ‘Known to God, an airman, RAF’. The diver made no attempt to identify the aircraft nor did he dig out any parts of the wreck that were buried. They were no threat to fishing nets.

The reclamation of land came to life again in the 1950s with the start of the building of the dykes for what would become the East Flevoland polder. The surrounding dykes were completed in 1957 and the slow process of draining the polder began. There was an important element which would complicate the working practices and even add danger. The floor of this section of the Ijsselmeer was known to be littered with wrecks of crashed aircraft, some of whose guns, ammunition and unexploded bombs still lay in the mud.

The task of making the area safe and removing all the wreckage was the responsibility of the Luchtmacht Bergingsdienst - the Aircraft Excavation Service of the Royal Netherlands Air Force. They were called into action early when a group of teenagers were found experimenting with the machine guns from a Wellington (not the Wellington mentioned above).

The task of making the area safe and removing all the wreckage was the responsibility of the Luchtmacht Bergingsdienst - the Aircraft Excavation Service of the Royal Netherlands Air Force. They were called into action early when a group of teenagers were found experimenting with the machine guns from a Wellington (not the Wellington mentioned above).

Just getting to the wrecks was a difficult task. As the water level fell it might become possible to wade out to a wreck to inspect it but the surface needed to be firm enough for lifting equipment - mobile cranes - to drive there. The usual practice was to lay a temporary road for diggers to drive out and build a coffer dam around the wreck. The water inside the dam was then pumped out and the liquid mud in and around the wreck sieved to find small pieces, any one of which might have markings which could identify the aircraft. (A coffer dam built in 2016 to recover a Wellington cost more that 1 million Euros).

A wreck which quickly surfaced, fin first, was an almost complete B-17 which had been neatly ditched. Its bomb bay contained no fewer than 94 light bombs.

Other aircraft had not arrived so tidily. Fragments of the fuselage of Lancaster ED357 (which was shot down on the night of 12th June, 1943) were spread over a 50 yard square, the largely intact starboard wing was 1,500 yards away and other widely scattered pieces were still emerging from the mud 12 months later. At the other end of the compactness scale was a Ju 88D-2 which had entered the water in an 80° dive. One item recovered from this was an intact bottle of Eau-de-Cologne. Does the vintage of perfume add value?

Surprisingly, one of the first wrecks to be recovered was not of WWII origin. It was a Netherlands Air Force Meteor T.7 which had been lost in 1950. The only other notable non-WWII recovery was from WWI - the engine, undercarriage and metal parts of a Gotha G IV. Built for the Luftstreitkräfte in 1913 it crashed in the Ijsselmeer in 1917. Its parts were cleaned up and sent to the Air Force Museum. Very little of the other wreckage was saved from the scrap heap.

There was quite a strong body of opinion that the clearing of wreckage was necessary just to make the ground safe and free of anything that might damage farm machinery. For the Luchtmacht Bergingsdienst to act like accident investigators or archaeologists, searching records to unearth all the circumstances behind the crashes was considered by some to be time consuming, costly and entirely unnecessary. There was a stronger counter view, held particularly by the wartime generation, who had a great deal of respect for the RAF. It was not unusual for British visitors to Holland, even many years later, to be thanked for Operation Manna, when Lancasters dropped over 7,000 tons of food to the starving population in the latter days of the war and saved many lives. So the sensitive handling by the Bergingsdienst of any casualty remains was greatly approved of and followed with interest.

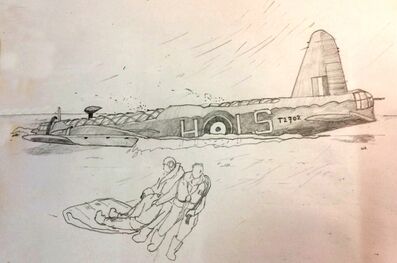

To get the full story of one incident involved a search through German as well as RAF records. On 10th February, 1941 Wellington Ic T2702 of 15 Sqn. raided Hanover and set course for home. As they flew over Holland they were detected by a Freya radar station. Each radar station controlled a night fighter patrolling in its box. Hauptmann Walter Ehle’s Me 110 was directed towards the Wellington. He soon picked it up in the moonlight and attacked. A petrol tank was holed and the Wellington burst into flame. The rear gunner, Sgt John Hall, although wounded in the legs, returned fire before the Wellington dived away. The pilot, Sgt. William Garrioch opted to belly land on the frozen Zuider Zee.

When the Wellington came to a halt the nose was buried in the ice. The body of Sgt. Glyndwr Reardon was trapped inside. The uninjured survivors. Navigator Sgt Robert Belioley, Engineer Sgt. William Jordan and Wop/AG Sgt Hardie Hedge (NZ) pulled John Hall out of the rear turret. They opened a parachute and put Hall on it, dragging it after them as they walked over the ice to reach land. There was a bitterly cold east wind blowing and they struggled on all night and into the following day. It was twelve hours before they reached land and met some German soldiers, who took these photographs

There was quite a strong body of opinion that the clearing of wreckage was necessary just to make the ground safe and free of anything that might damage farm machinery. For the Luchtmacht Bergingsdienst to act like accident investigators or archaeologists, searching records to unearth all the circumstances behind the crashes was considered by some to be time consuming, costly and entirely unnecessary. There was a stronger counter view, held particularly by the wartime generation, who had a great deal of respect for the RAF. It was not unusual for British visitors to Holland, even many years later, to be thanked for Operation Manna, when Lancasters dropped over 7,000 tons of food to the starving population in the latter days of the war and saved many lives. So the sensitive handling by the Bergingsdienst of any casualty remains was greatly approved of and followed with interest.

To get the full story of one incident involved a search through German as well as RAF records. On 10th February, 1941 Wellington Ic T2702 of 15 Sqn. raided Hanover and set course for home. As they flew over Holland they were detected by a Freya radar station. Each radar station controlled a night fighter patrolling in its box. Hauptmann Walter Ehle’s Me 110 was directed towards the Wellington. He soon picked it up in the moonlight and attacked. A petrol tank was holed and the Wellington burst into flame. The rear gunner, Sgt John Hall, although wounded in the legs, returned fire before the Wellington dived away. The pilot, Sgt. William Garrioch opted to belly land on the frozen Zuider Zee.

When the Wellington came to a halt the nose was buried in the ice. The body of Sgt. Glyndwr Reardon was trapped inside. The uninjured survivors. Navigator Sgt Robert Belioley, Engineer Sgt. William Jordan and Wop/AG Sgt Hardie Hedge (NZ) pulled John Hall out of the rear turret. They opened a parachute and put Hall on it, dragging it after them as they walked over the ice to reach land. There was a bitterly cold east wind blowing and they struggled on all night and into the following day. It was twelve hours before they reached land and met some German soldiers, who took these photographs

Two days later, the Wellington was still visible sitting on the ice some 15 kms from land. It was visited by a German with a camera who later made this composite drawing of the incident.

A week later, the Wellington broke through the ice and sank to the lake bed. Twenty six years later - 1967 - the last few parts of the front turret were dug out, still containing some remains. The ‘Known to God’ headstone was replaced with one bearing the name of Sgt. Glyndwr Reardon.

Many of the salvaged parts reveal no interesting story. Often it is possible only to identify the type of aeroplane and occasionally the serial number. So the scrap heap receives bent metal from anonymous Lancasters, Halifaxes, Stirlings, B-17s, Liberators and Spitfires - from Bf 109s and 110s, and the occasional Hampden or Lightning. Try as they might the Bergingsdienst could find no explanation for the (unfired) German ammunition in the fragments of a Mosquito, although it did have German markings.

Every wreck is subject to research, which can go on for years. The diligence of the investigators is much appreciated by relatives of those previously listed as ‘missing’. Many services have been held for burial or commemoration of those who died, all well attended by Dutch people. The funeral is of two Polish airmen. No relatives could be traced. The memorial is to a Canadian airman - the engine of his Stirling

Every wreck is subject to research, which can go on for years. The diligence of the investigators is much appreciated by relatives of those previously listed as ‘missing’. Many services have been held for burial or commemoration of those who died, all well attended by Dutch people. The funeral is of two Polish airmen. No relatives could be traced. The memorial is to a Canadian airman - the engine of his Stirling

The wreck recovery work is still going on, in the polders and in the Ijsselmeer. A film was made in 1979 which you can see here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gTpAXE4WIJM. You have to tolerate a rather overblown introduction and some vintage adverts but the meat of the film is excellent - and you’ll see ex-Sgt John Hall. (A comment by the Dutch - they wished the narrator had pronounced Ijsselmeer as 'Eisselmeer', not 'Isselmeer').