The Many Lives of Shoo Shoo (Shoo) Baby (Sept 2016)

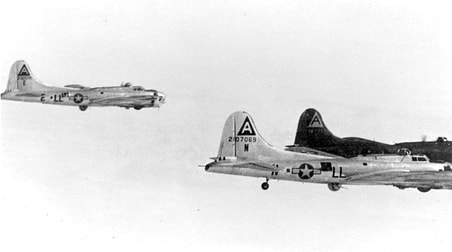

‘Shoo shoo, baby. Your papa’s off to the seven seas’, sang the Andrews sisters. The song was a hit for Tech Sgt Henry ‘Hank’ Cordes, a crew chief with the 401st Bomb Squadron at Bassingbourn. When a new B-17 was allocated to him he decided to name it ‘Shoo Shoo Baby’. It already had an official name (number), of course. B-17G-35-BO 42-32076 finally rolled off Boeing's production line in Seattle in March 1944, with the important numbers painted on the Technical Data Block on the port side of the nose.

(Incidentally, the '42' at the beginning of the number is often thought to indicate the year when the aeroplane was built. Not so. Officialdom is more interested in recording the Fiscal Year in which the order was placed, in this case, 1942).

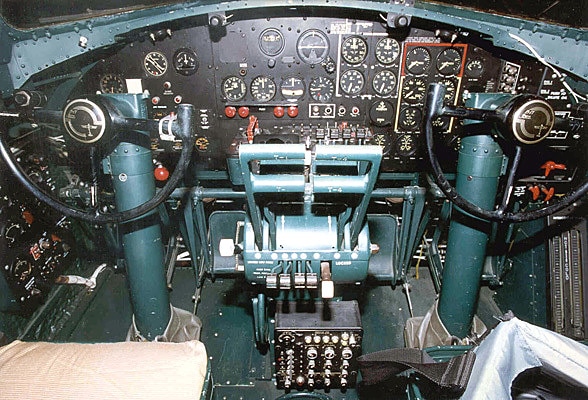

There was another, very unofficial marking on Shoo Shoo Baby. The pilot who collected it from Burtonwood on 23 March 1944, 2nd Lt Paul G McDuffee, was so impressed with its handling that he scratched his name under the control wheel.

Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby (note the addition of another Shoo which was to echo what the Andrews sisters really sang) completed 22 missions, not all with the same crew and here she is, LL-E on the left, in action on one of them.

On 29 May, 1944, 2nd Lt Robert J. Gunther flew the 23th operation, an attack on the Focke-Wulf works in Posen (now Poznan in Poland), 150 miles east of Berlin. Approaching the target, the number three engine lost oil pressure. The prop wouldn’t feather and the drag from the windmilling engine caused them to drop out of the formation.

On 29 May, 1944, 2nd Lt Robert J. Gunther flew the 23th operation, an attack on the Focke-Wulf works in Posen (now Poznan in Poland), 150 miles east of Berlin. Approaching the target, the number three engine lost oil pressure. The prop wouldn’t feather and the drag from the windmilling engine caused them to drop out of the formation.

Gunther continued to the target, dropped the bombs and turned for home, heading towards the Baltic. Although the main formation was being attacked by fighters, Shoo Baby was ignored. Then a second engine failed and the pilot asked the navigator for a course to Sweden. Losing height rapidly, the crew jettisoned equipment and guns, though the ball turret refused to drop.

As a third engine failed, a Swedish fighter flew alongside and led them to Malmo airfield where they followed a B-24 into land. Shoo Baby was one of eight US bombers to land in Sweden that day.

As a third engine failed, a Swedish fighter flew alongside and led them to Malmo airfield where they followed a B-24 into land. Shoo Baby was one of eight US bombers to land in Sweden that day.

In October, the Swedes struck a deal with the US government. They agreed to release 300 interned aircrew, with a promise that they would not return to combat, in exchange for nine B-17s. One of these was Shoo Baby.

Seven of the B-17s were converted into 14 seat passenger aircraft with ‘Sweden’ painted in large yellow letters on the side. One of the first flights in November ’44 was to Prestwick in Scotland.

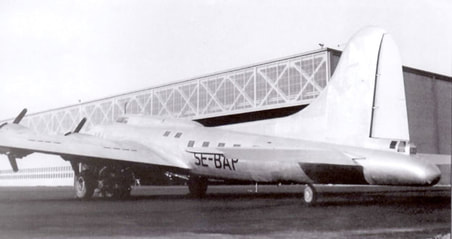

Shoo Baby, now registered SE-BAP, was flown to Heathrow in early November 1946 and transferred to the Danish Airline DDL and re-registered OY-DFA. Later that month it arrived at Blackbushe with 22 passengers. The port landing gear refused to come down. The one-wheel landing caused little damage and no injuries but led to a new paint job.

Named ‘Stig Viking’ it was used on the Copenhagen-Nairobi route, later extended to Johannesburg.

Converted bombers soon became uncompetitive as airliners and DDL were glad to sell Stig to the Danish Army Air corps who were going to use it as a photographic aircraft for the Danish Geodetic Institute.

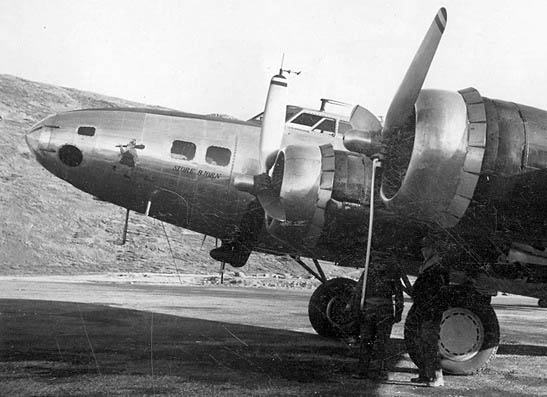

Three cameras were fitted in the lengthened nose and a 1400 litre fuel tank installed in the bomb bay. With a new military registration, 67-672, it was named ‘Store Bjørn’ (Ursa Major). From 1949 to 1953 it flew navigation tours of Sweden and Norway but spent much of its time in Greenland on extensive photographic surveys.

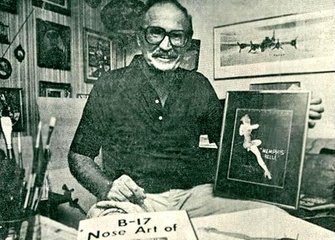

If it’s a B-17 it’s got to have some nose art

Several times, its work was interrupted by search and rescue missions in Greenland and in 1953 it ferried emergency supplies to Holland after its great flood disaster. It was not flown after this and in October 1954 Store Bjørn was officially decommissioned and placed in storage.

The following year, it attracted the attention of the French aerial mapping company Instituit Geographique National who already were using a fleet of twelve B-17s. They bought Shoo Baby and it was flown to their base at Creil, near Paris in April 1955. Modified yet again with two cameras fitted in the belly it was re-registered F-BGSH.

The following year, it attracted the attention of the French aerial mapping company Instituit Geographique National who already were using a fleet of twelve B-17s. They bought Shoo Baby and it was flown to their base at Creil, near Paris in April 1955. Modified yet again with two cameras fitted in the belly it was re-registered F-BGSH.

For the next six years it was used in a worldwide photography programme. On 15 July 1961 it was damaged in a collision. After 17 years active service and a flight time of 3364 hours it was pushed into a corner of the airfield and gently cannibalised.

Almost forgotten, it was rediscovered 11 years later by Steve Birdsall, an Australian writer with a keen interest in WWII US bombers. He was able to confirm it as a combat veteran by the still visible scratch marks made by 2nd Lt Paul McDuffee. Birdsall contacted the USAF Museum and this triggered negotiations between the US and French governments. The satisfactory outcome was the donation of Shoo Baby to the USAF Museum. (The Swedes had shown some interest but nothing came of it).

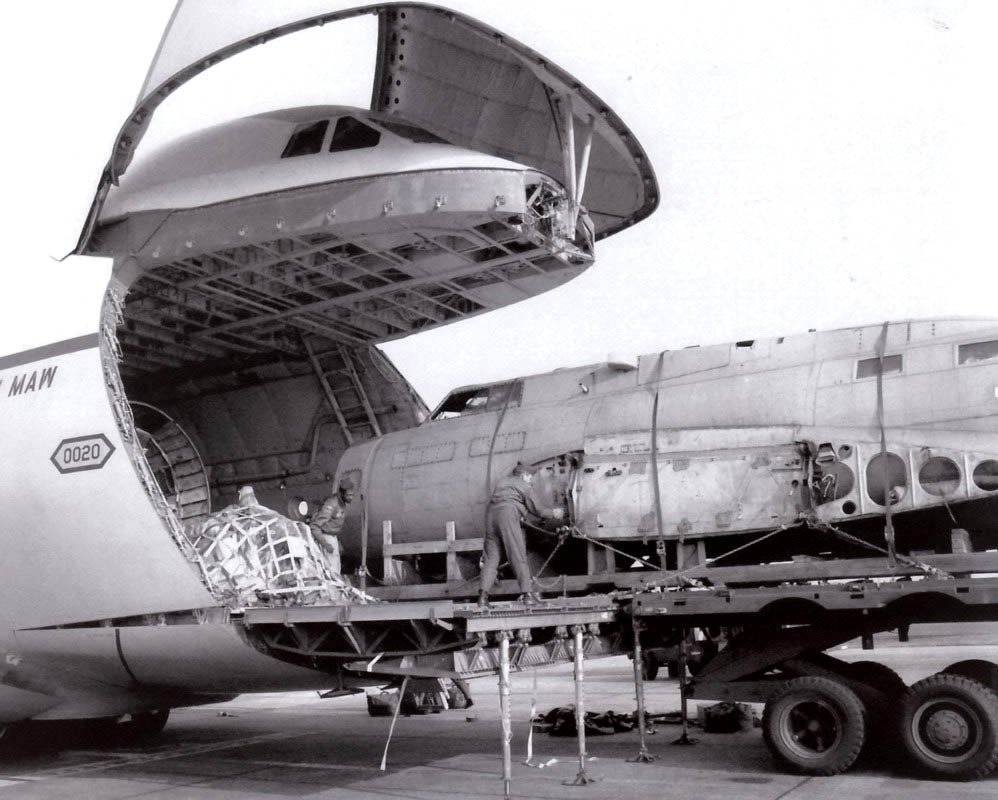

In June 1972 a team from Rhein-Main AFB USAF (Europe) was sent to dismantle the B-17. Oddly, they were given just two weeks to do the job which resulted in some less-than-careful removal of components. Everything that could be salvaged was packed into 27 crates and trucked to Frankfurt. It all went into a C-5 Galaxy and was flown to the USAF Museum at Wright-Paterson AFB at Dayton, Ohio.

In June 1972 a team from Rhein-Main AFB USAF (Europe) was sent to dismantle the B-17. Oddly, they were given just two weeks to do the job which resulted in some less-than-careful removal of components. Everything that could be salvaged was packed into 27 crates and trucked to Frankfurt. It all went into a C-5 Galaxy and was flown to the USAF Museum at Wright-Paterson AFB at Dayton, Ohio.

There, sadly, it suffered another long period of neglect because there were no funds for any kind of restoration. Until . . .

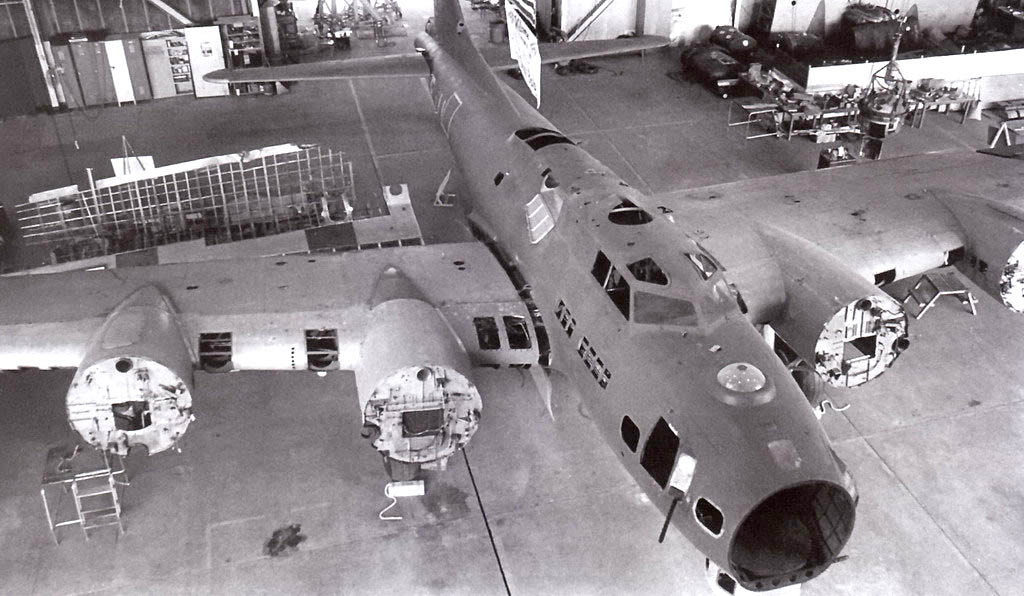

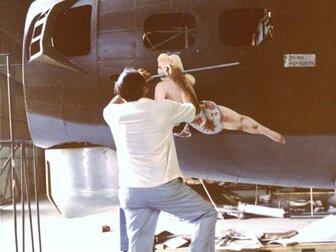

In 1978 a Reserve AF unit, the 512th Military Airlift Wing based at Dover AFB Del. was looking for a PR and maintenance training project. They thought that Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby would be just the thing to occupy their spare time. The crates took to the road again.

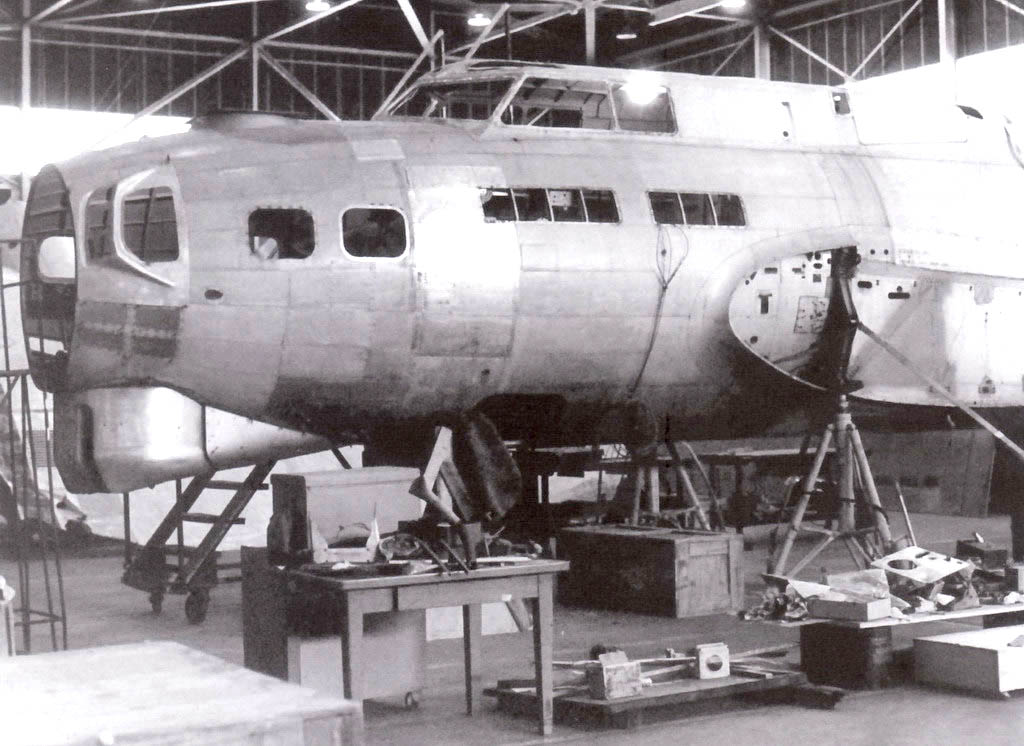

The restoring team soon realised that, although many parts were missing and all the modifications that had been added over the years of changing ownership had to be removed, the basic airframe was sound enough to be restored to flying condition.

In 1978 a Reserve AF unit, the 512th Military Airlift Wing based at Dover AFB Del. was looking for a PR and maintenance training project. They thought that Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby would be just the thing to occupy their spare time. The crates took to the road again.

The restoring team soon realised that, although many parts were missing and all the modifications that had been added over the years of changing ownership had to be removed, the basic airframe was sound enough to be restored to flying condition.

They aimed to make it as original as possible but had to make a decision about the finish. Shoo Baby had been delivered in olive drab camouflage and its name was first added in Gothic script. The nose art wasn’t added until after the USAAC order to remove all camouflage and Shoo Baby was stripped down to bare metal. Restoring it to its natural metal finish would make all the sections which had to be replaced too obvious so it was decided to paint the airframe olive drab.

One of the visitors to Dover was Paul, now Colonel (rtd), McDuffee. ‘I’ve just got to go over and kiss her’ he said. His delight at the reunion was clouded when he saw the name on the nose. He remembered his old companion as Shoo Shoo Baby. The third Shoo was added some time after he had completed his 25 missions and returned home. He began a campaign to have the offensive ‘Shoo’ removed and started a long and acrimonious correspondence with the ‘expert’ researchers who used the photograph taken in Sweden to ‘prove’ that McDuffee was wrong. His furious response failed to get the desired effect. He kept going until the day he died ‘up to the ears with all this horse hockey’.

Another visitor was George Bogert who couldn’t remember exactly how many missions he had flown in Shoo Baby’s ball turret. He could clearly remember how cold it was. It might have given him some little glow had he known that post-war analysis had shown that, statistically, the ball turret was the safest seat in a B-17.

Another visitor was George Bogert who couldn’t remember exactly how many missions he had flown in Shoo Baby’s ball turret. He could clearly remember how cold it was. It might have given him some little glow had he known that post-war analysis had shown that, statistically, the ball turret was the safest seat in a B-17.

The painstaking restoration took 60,000 man hours over a 10 year period. Finally, it was ready for its last flight. On 14 October 1988, Shoo Baby flew from Dover AFB to Dayton, Ohio where it is displayed as one of the major exhibits in the WWII Gallery of the National Museum of the U S Air Force.