Gliders at War (Feb 2016)

In the beginning, there was gliding, when man learned how to make wings that would allow him to fly. Then the Wright brothers’ practical engine relegated gliding to an emergency procedure. It was the Germans’ reaction to the Versailles Treaty that developed gliding into a sport but it was the Russians who took it to war. They conceived the idea of dropping troops by parachute and added cheap towed gliders both to increase the numbers of paratroops and carry cargo. It was a short step to decide to release the gliders to make a silent approach carrying soldiers who didn’t need to be trained as parachutists. They introduced this to their 1935 manoeuvres. An interested observer was Luftwaffe Colonel Kurt Student. He eagerly took this idea home and was allowed to form a Fallschirmjäger division of paratroops and gliders.

The Germans took their sport gliding seriously and had a special research institute, Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug. Its chief designer, Hans Jacobs, was chosen to design the sailplane intended for the 1940 Olympic games. He was given a specification for an assault glider and produced the DFS 230 which carried nine troops crammed in behind the pilot or 1200 kg of cargo. Its good gliding angle, 1:18, allowed it to be released from tow far from its target. Dropping the wheels after take-off it landed on its skid which acted as a brake, but not effectively enough. Tests of an under-fuselage hook – a sort of land anchor – proved far too effective. In a test by the ubiquitous Hanna Reitsch she was knocked out by the sudden stop. A tail parachute proved to be much better and allowed an approach as steep as 80 °.

The Germans took their sport gliding seriously and had a special research institute, Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug. Its chief designer, Hans Jacobs, was chosen to design the sailplane intended for the 1940 Olympic games. He was given a specification for an assault glider and produced the DFS 230 which carried nine troops crammed in behind the pilot or 1200 kg of cargo. Its good gliding angle, 1:18, allowed it to be released from tow far from its target. Dropping the wheels after take-off it landed on its skid which acted as a brake, but not effectively enough. Tests of an under-fuselage hook – a sort of land anchor – proved far too effective. In a test by the ubiquitous Hanna Reitsch she was knocked out by the sudden stop. A tail parachute proved to be much better and allowed an approach as steep as 80 °.

The DFS 230’s first operation was on 10 May 1940 - the capture of the Belgian Eben Emael fortress. This underground complex had many guns mounted in cupolas overlooking several bridges across the Albert Canal which the Germans needed to cross for the invasion of Belgium and France. The plan was for 85 men in 11 gliders to be released from their Ju 52 tugs at 7000 feet twenty miles from the fort. A snapped tow rope caused one glider to land in Germany and another released prematurely. This one carried the officer commanding the operation. He urgently called for a tug to land in the field by his glider. He reached the fort rather late but the assault was still going on so he won his medal.

Other glider-borne troops were used to seize and prevent demolition of the bridges. In total 493 troops landed in 42 gliders but it was the capture of the ‘impregnable’ fort and its garrison of 800 men by just 75 soldiers at a cost of 6 killed and 19 wounded that had the dramatic impact. The use of gliders with their silent approach and precision flying seized the attention of the defenders of the British Isles.

In June 1940 Philip Wills was heavily occupied as OC No 1 Ferry Pool of the Air Transport Auxiliary. Before the war he had been one of the country’s leading soaring pilots. All gliders were grounded ‘for the duration’ and Wills’ beautiful German-built Minimoa was in storage. Despite the importance of his job he was surprised to receive an urgent instruction to leave his post and take his sailplane to a secret establishment at Worth Matravers in Dorset.

There he met a small number of other glider pilots, also with their sailplanes. They learned about the existence of RDF (radar) and told they were to test the capability of the experimental scanners to detect wooden gliders, widely expected to be part of an invasion force. Almost as big a surprise was to learn that the tow planes were two old Avro 504s, their roots firmly in WWI yet still capable of towing the sailplanes out of a field next to the jumble of huts and scanners. Released at 10,000ft over the Channel, they were to return by a varying route which, hopefully, would be successfully plotted by RDF.

Worth was only 60 miles from the French coast and as the Battle of Britain developed air raid warnings were frequent, interrupting the work. A rule to suspend flying during an alert had to be ignored. On one occasion the tow plane and glider were being plotted on their slow 45 mph climb when another plot coming from France moved onto the screen. The plots converged but luckily the altitudes were very different. There was much speculation about the German pilot’s reactions had he met a WWI biplane towing a German sailplane in mid-Channel.

As the tests progressed, the gliders were asked to return at lower and lower heights. Inevitably, the day arrived when Wills realised that he was too low to get over the top of the cliffs. As he disappeared from their view the watchers in the field ran to the cliff top to see the crash. Wills was less concerned because he knew that the sea breeze striking the cliff would provide a turbulent up-draught. His ‘rescuers’ got to the cliff’s edge and could see no glider. Wills had worked his way along face of the cliff and climbed easily to land behind them all.

Worth was only 60 miles from the French coast and as the Battle of Britain developed air raid warnings were frequent, interrupting the work. A rule to suspend flying during an alert had to be ignored. On one occasion the tow plane and glider were being plotted on their slow 45 mph climb when another plot coming from France moved onto the screen. The plots converged but luckily the altitudes were very different. There was much speculation about the German pilot’s reactions had he met a WWI biplane towing a German sailplane in mid-Channel.

As the tests progressed, the gliders were asked to return at lower and lower heights. Inevitably, the day arrived when Wills realised that he was too low to get over the top of the cliffs. As he disappeared from their view the watchers in the field ran to the cliff top to see the crash. Wills was less concerned because he knew that the sea breeze striking the cliff would provide a turbulent up-draught. His ‘rescuers’ got to the cliff’s edge and could see no glider. Wills had worked his way along face of the cliff and climbed easily to land behind them all.

To be absolutely sure that that radar wasn't just detecting the many metal parts of the gliders, Slingsby, the glider manufacturer, was asked to make an entirely non-metal glider. The wires which operated the controls were replaced by wooden push rods, hinges were made of leather and so on. What became known as the 'Radar Kite' was towed out over the Channel and clearly seen by the radar. (This Radar Kite survived the war, its non-metallic wings were fitted to a standard fuselage and it flies today, often appearing at Shuttleworth displays.)

When the scientists were confident that they could detect wooden gliders the tests ended in mid-August on a day when one of the glider pilots watched a lone Heinkel near him being shot down. They were just in time to go. The next day, there were 300+ plots on the Worth screens.

Meanwhile the design and production of the British glider force was in full swing. The training of pilots began on requisitioned civilian gliders but soon the GA Hotspur arrived at the school at Haddenham, near Thame. Carrying 8 troops and two pilots it was overshadowed as an assault glider by the Airspeed Horsa and used only for training.

When the scientists were confident that they could detect wooden gliders the tests ended in mid-August on a day when one of the glider pilots watched a lone Heinkel near him being shot down. They were just in time to go. The next day, there were 300+ plots on the Worth screens.

Meanwhile the design and production of the British glider force was in full swing. The training of pilots began on requisitioned civilian gliders but soon the GA Hotspur arrived at the school at Haddenham, near Thame. Carrying 8 troops and two pilots it was overshadowed as an assault glider by the Airspeed Horsa and used only for training.

The much larger Horsa had the capacity for 28 fully armed troops, jeeps, anti-tank guns or a howitzer. The main wheels of its tricycle undercarriage could be jettisoned but seldom were. It was fitted with huge flaps which reduced its gliding angle to 1:1½. A version was developed to carry more than 7000 lbs of cargo. There was even a proposal to fit in two 4000 lb bombs though the practical purpose for that is unclear. Some Horsas had a hinged nose but the usual method for a speedy deployment of troops after landing was to blow the four explosive bolts which held on the rear fuselage.

The Horsa’s debut was Operation Freshman which, sadly, was a disaster. In November 1942 two Horsas carried engineers and Commandos to attack the heavy water plant in Norway. In foul weather one tow rope broke and the glider crash landed. The other glider and its Halifax tug flew into a mountain killing everyone on board. After that, the Horsa really proved its worth. Forty were towed to North Africa and 37 were used in the invasion of Sicily. They took the lead in the 1944 Operation Overlord with spectacular success at Pegasus Bridge and later at Arnhem and the crossing of the Rhine. Around 4000 Horsas were built, 400 of which were used by the US Army

The largest glider used by the Allies was the GA Hamilcar intended to carry up to 17,600 lbs of heavy equipment, a light tank or two Bren carriers.

On the approach to the target landing area the release of the tow rope would be the signal for the vehicle crews to start their engines, the exhaust fumes being led outside through a flexible duct. On landing, the two pilots would jump down and release the valves in the undercarriage legs to lower the glider onto its skids. As the vehicle rolled forward a pressure plate on the floor automatically swung open the hinged nose.

There were problems in production which delayed its entry into service. Although 410 were finally produced only 34 were available to take part in Overload and a similar number were used at Arnhem and the Rhine crossing in 1945.

There were problems in production which delayed its entry into service. Although 410 were finally produced only 34 were available to take part in Overload and a similar number were used at Arnhem and the Rhine crossing in 1945.

The US glider was the Waco CG-4A, carrying fewer troops than the Horsa (13 plus 2 pilots) but produced in US-style quantities, more than 12,000. At least 1000, known as Hadrians, were used by the British army. They were delivered in crates, five per glider. The crates themselves proved to be useful at overcrowded Haddenham because they converted easily into temporary living quarters.

After assembly the gliders were test flown, usually completed in two or three launches to 4000 ft. The tests included a dive to 150 mph, the maximum permitted speed. On one flight the pilots, an army Staff Sergeant and an RAF Warrant Officer, decided that they could easily recover from the dive by looping the lightly loaded glider. The unit’s CO heard about this and the crew were on the Major’s carpet. Not for long. The next day the Major was looping too, though he banned it after that in case his superiors thought he was treating their gliders casually.

|

The US Army sent troops for other tests. After the glider landed, using its powerful wheel brakes, the occupants practised emerging into battle. Raising the nose took some time, maybe under fire, for the pilots to unstrap and clamber out of their seats. The troops suggested lifting the nose with the strapped in pilots immediately, allowing the jeep and its occupants to drive out into action. The pilots could then climb down at their leisure.

‘Hold on’, said a pilot, ‘if you stop the jeep just – there, we’ll unstrap and roll down into the back seats’. One broken ankle and one wrenched knee later, they went back to square one. |

Not all Hadrians came as deck cargo. In June 1943, the RAF decided, and they must have had a reason for it, to tow a Hadrian across the Atlantic. In Operation Voodoo, a Hadrian was loaded with 3360 lbs of medical and radio supplies – and flotation bags. The two Squadron Leader pilots flew behind a Dakota from Canada via Labrador and Iceland to Prestwick in Scotland. That took three days and involved 28 no auto-pilot hours on tow. Voodoo was never repeated.

Getting a glider to war required a suitable tow plane. It might sound easy to ’follow that tug’ but there are complications. The glider normally flies just above the turbulent wake of the tug and the pilot has an instrument which measures the tow rope’s ‘angle of dangle’ which helps to maintain position – particularly useful in the dark. The air is seldom smooth and the tow rope must be flexible enough to absorb shocks and that makes it act like a piece of elastic. If the tug flies into rising air the glider must climb to maintain position. When the glider hits the rising air and the pilot pushes down the nose, the glider accelerates and the tow rope goes slack. Soon it stretches and tightens propelling the glider forwards and upwards more vigorously so the rope goes slack again. If the stretch and slacken cycle is allowed to continue it quickly gets worse and could end in breaking the rope. A more stable towing position, occasionally used, is ‘low-tow’ when the glider is flown below the tug’s slipstream. The pilot can tell exactly where the tug’s wake is by the vibration of the fin and rudder if he gets too high. The disadvantage is the consequence of a rope-break when it would inevitably wrap itself around the glider.

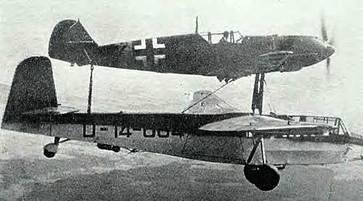

The Germans carried out tests to make towing easier. A Ju 52 had its rope coiled on a drum to vary the length deployed. The rope got shorter and shorter until it was replaced by a rigid bar, mounted on a gimbal and with a shock absorber. It worked, but introduced other problems. (After an otherwise trouble-free tow, one DFS 230 released and immediately went into a loop, so tight that the glider broke up). As well as towing, they tested carrying the glider. That led in a different direction - to the Mistel guided unmanned exploding bomber. (There were parallel thoughts in Allied minds with an untested proposal for a P-38 Lightning to lift a GA Hamilcar glider).

The Germans carried out tests to make towing easier. A Ju 52 had its rope coiled on a drum to vary the length deployed. The rope got shorter and shorter until it was replaced by a rigid bar, mounted on a gimbal and with a shock absorber. It worked, but introduced other problems. (After an otherwise trouble-free tow, one DFS 230 released and immediately went into a loop, so tight that the glider broke up). As well as towing, they tested carrying the glider. That led in a different direction - to the Mistel guided unmanned exploding bomber. (There were parallel thoughts in Allied minds with an untested proposal for a P-38 Lightning to lift a GA Hamilcar glider).

The tests went on to establish the requirements to achieve the stable towing of unmanned gliders. The first of these was a fuel tank which could be jettisoned after the tug had used the fuel. What else could be towed? How about - a footbridge? Build the bridge, with floats attached 2 - 3 metres apart, add a few pairs of wings and it could fly. It did -very well. Next, take it to the river and lower it gently into the water just upstream of the intended mooring point. When the line contacts the water, release it and the anchor on it will dig in and hold the bridge, the wings will unlock and float away. Bizarre as it seems, three aircraft delivered their loads and a serviceable footbridge was built and in use in half an hour.

Back to the serious war . . . In May 1941 the success of the Eben Emael operation encouraged Kurt Student, now a Major General, to plan the airborne invasion of Crete with supreme confidence. Paratroops and 80 assault gliders spearheaded the attack initially aimed at capturing airfields to be used by the fleet of 500 Ju 52 transports.

After a week of hard fighting the island was captured but the German casualties, more than 6,000, were so severe that Hitler refused to consider any further major airborne assaults.

There was another small, but notable, operation when 12 DFS 230 gliders were used to land troops to rescue Mussolini from the mountain hotel where he was being held prisoner (by the Italians) in September 1943.

There was another small, but notable, operation when 12 DFS 230 gliders were used to land troops to rescue Mussolini from the mountain hotel where he was being held prisoner (by the Italians) in September 1943.

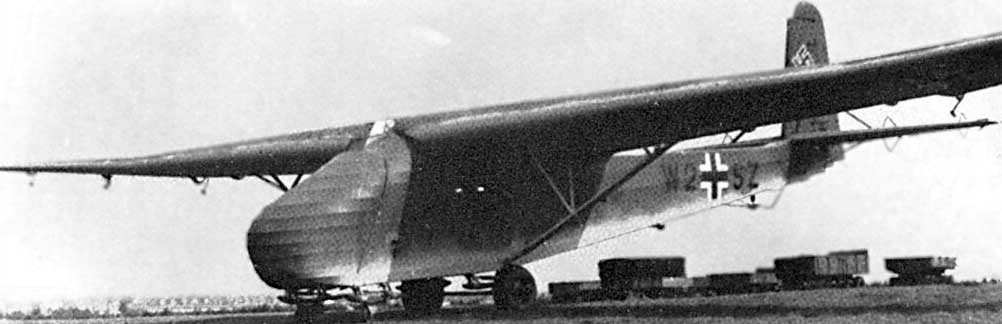

Larger gliders were built. The Gotha 242 could carry 20 troops and was used, mostly in the Mediterranean and North Africa, as a cargo carrier. The design of the Messerschmitt 321 Gigant was started as early as 1940, purely as a cargo carrier – its hold was the same size as a German railway flat car. 200 were built but they brought many problems. They were so big (empty weight 27,000 lbs, wingspan 180’) that they needed specialist vehicles for ground handling and special arrangements for getting them into the air.

At first the four engined Ju 290 had difficulty, not helped by the Gigant’s sluggish handling. The tests continued with booster rockets to help. Then the ‘troika’ - three carefully co-ordinated Me110s was used – and still needed rockets.

The troika was abandoned. A larger and more powerful tug was needed – and quickly. The solution was to stitch together two He 111s, adding a fifth engine at the junction. The pilot sat in the port fuselage, controlling the throttles of all five 1,340 hp engines. Oddly, control of the radiators was shared with the co-pilot in the starboard fuselage, each looking after his own side. It all worked quite well and, although only 12 He 111z came into service, they could launch a fully loaded rocket-assisted Me 321.

The troika was abandoned. A larger and more powerful tug was needed – and quickly. The solution was to stitch together two He 111s, adding a fifth engine at the junction. The pilot sat in the port fuselage, controlling the throttles of all five 1,340 hp engines. Oddly, control of the radiators was shared with the co-pilot in the starboard fuselage, each looking after his own side. It all worked quite well and, although only 12 He 111z came into service, they could launch a fully loaded rocket-assisted Me 321.

The cumbersome ground handling of larger gliders was overcome by fitting them with engines. The Me 321 became the 323 by using six French Gnome et Rhône radials with an engineer sitting in each wing between the inner and middle engines. However, as powered transports they are outside the remit of this article.

After Crete, the Germans no longer considered gliders practical for assault. They continued to be used extensively as transports, particularly in Russia where the fluid battle lines left isolated pockets of soldiers needing supplies. And although they had started it all the Russians built only 1000 light gliders and used them in a similar fashion. Other than using 32 A7 gliders to lead the Dnieper river crossing in 1943 they carried out no significant glider-borne attack.

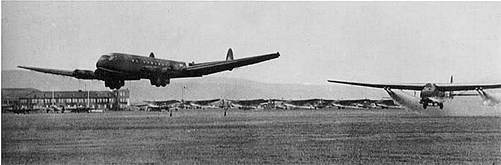

The transport role was useful to the Allies in Burma. The Chindit force, operating behind the Japanese lines, depended entirely on airdropped supplies. A force of engineers, equipped with tractors and bulldozers, landed in Waco CG-4A (Hadrian) gliders and built airstrips suitable for Dakotas to use. Some gliders were flown back to India, often using the ‘snatch-launch’ system.

The glider was parked, facing into wind, and a short nylon towrope attached. This ended in a loop which was hung on two 12’ poles, set 20’ apart. The approach line for the low-flying Dakota was marked with a white line, often just a row of white-painted helmets. As it swept past a grapple caught the loop to launch the glider which accelerated from standstill to 120 mph in 7 exciting seconds. The towrope was pulled off an inertia reel drum inside the Dakota which effectively reduced the acceleration force on the glider to just 7/10 of 1G.

The most extensive use of the snatch-launch system was after the Rhine crossing in Spring 1945. Of the 300 CG-4s used in the assault 60% were returned to flyable condition and many were lifted off carrying wounded soldiers. It proved to be the most effective way to get the casualties quickly to a hospital.

[After the glider released at its destination, the tug reeled in the tow cable – but only as far as the hook, leaving the loop trailing behind. Then, reverting to really basic technology, a crew member leaned out of the open door of the Dak, wielding a boat hook in the slipstream, unhooked the loop and pulled it in hand over hand].

A rescue in the Far East became widely known because of the presence of a journalist with the rescue party. It got a lot of publicity and a book was later written about it. Although in May 1945 there were still Japanese troops fighting in New Guinea, mostly in coastal areas, a sightseeing flight was organised for 24 servicemen and women passengers in a C-47 to a remote valley deep in the interior. It failed to return. It took four days for wide ranging air searches to find the three passengers who had survived when the C-47 crashed into a mountain. A rescue party of two paramedics dropped into the valley by parachute. Because no-one could predict the reaction of the local tribes 10 soldiers also dropped accompanied by the journalist.

A clearing was found that was large enough for a glider to land. It was dispatched loaded with the snatch-launch equipment and a single pilot. The first launch with the survivors was successful apart from some damage to the glider when it hit the top of the trees on take-off. A second glider brought out the rest of the party in two more lifts.

When the war came to an end the vast majority of gliders were scrapped or sold as surplus. Some were bought for conversion to caravans or garden sheds. However, most buyers seemed to be more interested in the robust packing cases which had a much more practical use.

The USAF maintained only one regiment using the CG-4s, which remained in service having little employment other than in exercises. Their last recorded ‘operational’ use was in the early 1950s when a group of research scientists were landed on and lifted off ice floes in the Arctic. All military glider operations were abandoned on 1st January 1953.

[After the glider released at its destination, the tug reeled in the tow cable – but only as far as the hook, leaving the loop trailing behind. Then, reverting to really basic technology, a crew member leaned out of the open door of the Dak, wielding a boat hook in the slipstream, unhooked the loop and pulled it in hand over hand].

A rescue in the Far East became widely known because of the presence of a journalist with the rescue party. It got a lot of publicity and a book was later written about it. Although in May 1945 there were still Japanese troops fighting in New Guinea, mostly in coastal areas, a sightseeing flight was organised for 24 servicemen and women passengers in a C-47 to a remote valley deep in the interior. It failed to return. It took four days for wide ranging air searches to find the three passengers who had survived when the C-47 crashed into a mountain. A rescue party of two paramedics dropped into the valley by parachute. Because no-one could predict the reaction of the local tribes 10 soldiers also dropped accompanied by the journalist.

A clearing was found that was large enough for a glider to land. It was dispatched loaded with the snatch-launch equipment and a single pilot. The first launch with the survivors was successful apart from some damage to the glider when it hit the top of the trees on take-off. A second glider brought out the rest of the party in two more lifts.

When the war came to an end the vast majority of gliders were scrapped or sold as surplus. Some were bought for conversion to caravans or garden sheds. However, most buyers seemed to be more interested in the robust packing cases which had a much more practical use.

The USAF maintained only one regiment using the CG-4s, which remained in service having little employment other than in exercises. Their last recorded ‘operational’ use was in the early 1950s when a group of research scientists were landed on and lifted off ice floes in the Arctic. All military glider operations were abandoned on 1st January 1953.

The Soviet Union, which had made the least use of assault gliders during the war kept them in their inventory after 1945. They even introduced a new glider, the Hamilcar-like Yak-14, big enough to carry 35 fully equipped troops. It made its mark in 1950 by becoming the first glider to fly over the North Pole.

In 1965 the last three glider infantry regiments were disbanded and the military glider became extinct.

In 1965 the last three glider infantry regiments were disbanded and the military glider became extinct.