The Piaggio Pegna Pc.7 (Dec 2009)

The Schneider Trophy competition for seaplanes was first announced in 1911. It was a contest for speed over a triangular course and became a vehicle for the competing nations to demonstrate their technical superiority. Any national aero club which won the race three times in five years would receive 75,000 francs and retain the trophy permanently. Whilst it might now seem odd for seaplanes to be the chosen configuration for speed the view was very different in the early years of aviation, partly because seaplanes could take advantage of almost unlimited take-off distances.

The Schneider Trophy seaplanes proved this point by regularly breaking the world speed record. When Britain won the trophy outright in 1931 the Supermarine S.6B was first to set the record at more than 400 mph (407.5 mph). 18 months later, the Italian Macchi MC.72, which had been plagued by engine problems during the race, raised the record to 424 mph and again to 440.681 mph in October 1934. This stood until Messerschmitt’s special Bf 109 reached 469.22 mph in 1939.

The races were held annually until 1927 when it was decided to allow more time for development by holding the event bi-annually. R J Mitchell set to work on a refinement of his winning S.5 with its Rolls-Royce engine. In Italy Fiat built a 1000 hp C.29 seaplane but it crashed during testing. Savoia-Marchetti’s S.65 used two 1000 hp engines in tandem.

Meanwhile, working with Piaggio, was Giovanni Pegna. He had trained as a marine engineer but later qualified as a pilot and transferred his interest to aircraft design. Increasing engine power was the obvious way to improve performance but Pegna was equally concerned with reducing drag, principally that of the floats.

The Schneider Trophy seaplanes proved this point by regularly breaking the world speed record. When Britain won the trophy outright in 1931 the Supermarine S.6B was first to set the record at more than 400 mph (407.5 mph). 18 months later, the Italian Macchi MC.72, which had been plagued by engine problems during the race, raised the record to 424 mph and again to 440.681 mph in October 1934. This stood until Messerschmitt’s special Bf 109 reached 469.22 mph in 1939.

The races were held annually until 1927 when it was decided to allow more time for development by holding the event bi-annually. R J Mitchell set to work on a refinement of his winning S.5 with its Rolls-Royce engine. In Italy Fiat built a 1000 hp C.29 seaplane but it crashed during testing. Savoia-Marchetti’s S.65 used two 1000 hp engines in tandem.

Meanwhile, working with Piaggio, was Giovanni Pegna. He had trained as a marine engineer but later qualified as a pilot and transferred his interest to aircraft design. Increasing engine power was the obvious way to improve performance but Pegna was equally concerned with reducing drag, principally that of the floats.

In his research he found a British patent for lifting the engine to clear the spray during take-off and landing. This would allow the hull to be much less deep.

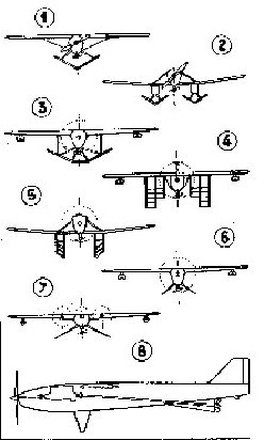

Another layout he considered was the retracting hull, just like that to be used by the Blackburn B.20 in 1940. Pegna went one step further. Small wings attached to the float would beneficially increase the wing area for take-off and alighting. In flight the float would retract and the planes would fit into the underside of the main wing. However, he was concerned about the aerodynamic interference between the wings as they came together and abandoned the plan as impractical.

Another layout he considered was the retracting hull, just like that to be used by the Blackburn B.20 in 1940. Pegna went one step further. Small wings attached to the float would beneficially increase the wing area for take-off and alighting. In flight the float would retract and the planes would fit into the underside of the main wing. However, he was concerned about the aerodynamic interference between the wings as they came together and abandoned the plan as impractical.

He turned his thoughts to the use of hydrofoils. A French patent had been filed by a M. Lambert in 1881 for a boat fitted with hydrofoils. Two Italians developed this and their boat reached a speed of 130 km/hr in 1906. Pegna had carried out a series of experiments with hydrofoils in 1917 and a paper he produced in 1921 set out a range of ideas on using them to replace high-drag floats.

For the Schneider Trophy race he decided to develop the No 8 layout. Surprisingly, it was not until 1928 that he discovered that this configuration had already been tested 16 years before. This example of advanced thinking deserves a closer look.

An RN Lieutenant, Dennistoun Burney first used the hydrofoil when he invented the mine-sweeping paravane before WWI. But it was another of Burney’s inventions which interested Pegna.

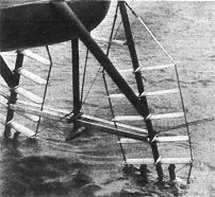

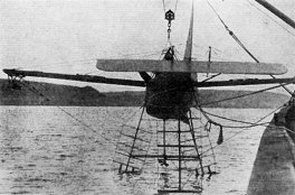

In 1912 Burney could see the role that submarines would play in warfare. Having flown in a Bristol Boxkite fitted with flotation bags he began work on an aeroplane that could be carried and launched by a submarine. The design emerged as an inflatable, which, when ready for flight would be driven by a marine propeller gradually rising from the water on a series of hydrofoils until the airscrew could be started for take-off.

The British and Colonial Aeroplane Company (Bristol) agreed to test the concept, using conventional construction for the airframe. The first prototype, the X.1 was unstable and insufficiently strong. X.2 was more robust and the engine was replaced by ballast. The tests were carried out by towing and it actually flew – on 21 September, 1912 – but it behaved like most kites and almost immediately side-slipped into the water.

X.3 was built with an engine, redesigned hydrofoils and contra-rotating marine propellors. Tests continued for a while but the emergence of more powerful and longer-range floatplanes and flying boats put paid to any further development.

(After WWI Burney became an MP, gained a knighthood and became Managing Director of the Airship Guarantee Company, a subsidiary of Vickers, who built the successful R-100. During WWII he worked on the development of an air-launched gliding torpedo and a gliding bomb).

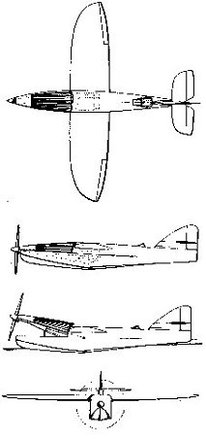

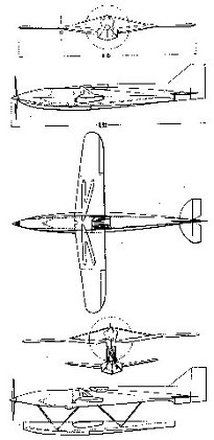

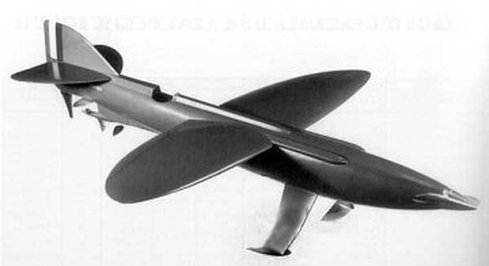

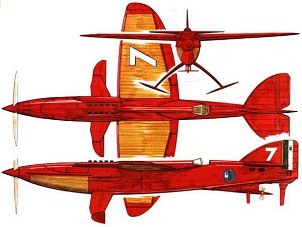

Pegna’s design for the 1929 race, the Piaggio-Pegna Pc.7, was constructed of double-skinned plywood sandwiching a layer of water-proof fabric. The fuselage had water-proof bulkheads and contained two thin corrugated aluminium flotation boxes. An 800-hp Isotta-Fraschini V-6 engine drove both a two-blade airscrew and a marine propeller at the tail via separate clutches and long shafts. Most of the upper wing surface was a coolant radiator. Oil cooling was by nose intakes opened in flight. The cleverly designed hydrofoils were set at the correct angle to give automatic lateral stability on the water.

The airscrew was feathered and held horizontally in line with the water surface until it was clear of the water. For take off the pilot started the engine and engaged the tail screw. This quickly lifted the aeroplane onto its hydroplanes when the pilot opened the carburettor air intake, applied full power and engaged the airscrew clutch. The prop automatically changed from feathered to flight pitch and a normal take-off run commenced. The projected maximum speed was 434 mph.

With so many new concepts to be tested, there were the inevitable problems. On one take-off attempt, the water screw had achieved lift onto the hydrofoils when an oil leak flooded the clutch and it slipped, dropping the aeroplane nose-first into the water. The clutches proved difficult to manage and a take-off was never achieved. Time ran out and the project was abandoned, to the relief of some of the pilots.

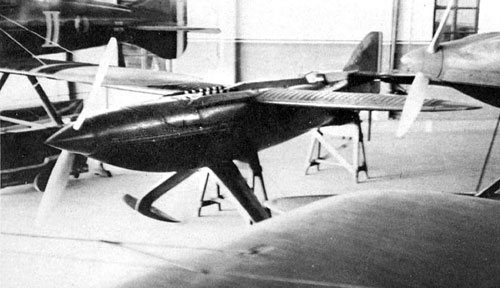

Could it have been made to work? Scale modellers have shown that it was a viable concept. They recreate the Schneider Trophy races and in the 1988 event the winner was – the Piaggio-Pegna Pc.7 The model , built by Alain Vassel, used its water screw to taxi out and lift onto the hydrofoils, the airscrew was engaged and it flew the required five laps at the highest speed of the day. It behaved impeccably in the air and on the water.