The Bungee – a Contraction Contraption Offering Fun and Fear. (Apr 2017)

It’s an oft-repeated truism that the sport of gliding grew out of the Versailles Treaty. Not strictly true, because the ban on military aircraft and engines in the treaty was for only six months. That gave time for the Military Inter-Allied Commission of Control to produce more specific restrictions which were not eased until 1926. By then, in Germany, there was a well-developed official encouragement of gliding (which was never mentioned in the Treaty) as a cheap and practical way of producing that essential cadre of potential pilots for future commercial and military use.

Otto Lilienthal had led the way, foot-launching his gliders from a hill, the Wright brothers used a rail and a falling weight, Percy Pilcher was towed into the air by a horse, then engines took over the launching. To get a glider airborne there was a more convenient way, the bungee, elastic strands inside a woven cotton sheath. Today we can buy bungee cords in many different thicknesses and we use them for many purposes. In WWI aviation, they were most commonly found wound around wheel axles as undercarriage suspension.

Simple and light gliders appeared from many workshops and clubs across Germany. Although higher performance gliders were soon developed which would discover and exploit thermal lift under clouds, the basic school glider was never replaced. Every pilot began his training on a Zögling (Pupil).

Simple and light gliders appeared from many workshops and clubs across Germany. Although higher performance gliders were soon developed which would discover and exploit thermal lift under clouds, the basic school glider was never replaced. Every pilot began his training on a Zögling (Pupil).

The best of these was the SG-38 Schulgleiter (School Glider) or Zögling whose plans were exported round the world. Over 10,000 were built. In the UK, R F Dagnall named theirs the Dagling (Dagnall’s Zögling!), Slingsby built the Grasshopper and Elliots of Newbury built the Eton. All were launched by a simple V-shaped bungee pulled by a gang of eager pupils waiting their turn.

You can see a launch here at the Wasserkuppe, the most famous German gliding site - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3cWraMdidGE.

You can see a launch here at the Wasserkuppe, the most famous German gliding site - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3cWraMdidGE.

Gliding developed more slowly in the UK. After a less-than-serious competition in 1922, little happened until the Austrian, Robert Kronfeld, flew some demonstration soaring flights over the South Downs in 1930. These generated enough excitement to spark the formation, during a taxi-ride, of the British Gliding Association. Clubs set themselves up all over the country and most started by building their own primary gliders. Bungee launches were used at some hill sites but more often the launching method was the more convenient winch.

There were few two-seat trainers available so students were solo from the start. The training was a long and seemingly interminable progression of short steps, wing balancing, ground slides, airborne slides, low hops and high hops.

The time spent actually in control of the glider was measured in seconds so it took many days training until the pupil could climb high enough to achieve the free glide of 30 seconds needed to be awarded an ‘A’ Certificate. The typical glider used for training was the Kirby Kadet. It was very basic, with no instruments, often no windscreen, but quite capable of flying circuits.

The time spent actually in control of the glider was measured in seconds so it took many days training until the pupil could climb high enough to achieve the free glide of 30 seconds needed to be awarded an ‘A’ Certificate. The typical glider used for training was the Kirby Kadet. It was very basic, with no instruments, often no windscreen, but quite capable of flying circuits.

On the outbreak of war in 1939, all private flying and gliding ceased. Several grounded pilots offered to rig their gliders and train Air Training Corps cadets and in 1941 gliding training began. All instruction was by the solo method (ground slides, low hops, etc) and this continued until 1950 when the T-21 Sedbergh two-seat trainer was introduced.

Long before the ATC was formed, in fact, since the 1850s, military cadet training had been established at many public schools. This became more regulated in 1948 when the Combined Cadet Force was formed with separate army, navy and air force sections at each school. This arrangement seemed to work well but there were problems. The army section had fun crawling about on field exercises and the navy section had one or more boats to splash about in. The air cadets had few practical things to get their hands on. There are only so many times that you can take apart the breech block of a Browning .303 to identify the rear-sear-retainer-keeper Also lectures on navigation and meteorology were too much like being in school. Then someone had a bright idea. Why not give them primary gliders!

Slingsby Sailplanes and Elliotts of Newbury got orders to produce dozens of primary gliders. Slingsby’s T-2 Primary design of 1934 was abandoned and he produced the T-38 Grasshopper, 115 of them, initially by taking the wings of unsold Kadets and adding the skeleton fuselage. Elliotts started from scratch and their Eton, 80 built, was reputed to be nicer to fly. A subtle distinction. The performance of both was in the brick-built category.

They were delivered to schools across the land and got a mixed reception. A few, very few, were welcomed by those CCF officers who knew something about gliders. Most saw them as a nuisance – where to store them, where to ‘fly’ them (‘I’m having no furrows on my cricket pitch’) and finding someone who would agree to learn to be an instructor. They were to be serviced and repaired by Mobile Glider Servicing Parties who visited every school at intervals. One party was greeted with ‘Oh. The glider. It’s in that shed. The footrest thingy at the front seems to be a bit loose and when you move it there’s something flopping about at the back’.

Where keen instructors were available they began training cadets by wing balancing with the glider mounted on a tripod facing into wind followed by ground slides, then hops, seldom exceeding 20 feet above the ground. One cadet came back from a course at a gliding school where he had qualified with three solo circuits from winch launches to 1000 feet. He was offered a bungee launch in the primary and automatically pulled the stick back, zooming up to a previously unseen height. The instructors were so alarmed that they never used the glider again. CCF primaries soldiered on until the 1980s when they were replaced by flight simulators – not so much fun, but much less effort.

Instructor training, both for the CCF and also for the instructors who flew at the 27 weekend ATC Gliding Schools based at RAF airfields was the responsibility of the two Gliding Centres which were RAF units, part of Home Command. CCF instructor courses were run in the school holidays and included instruction in winch-launched Cadet Mk 3s to solo circuit standard which gave instructors a better perspective on their usual work. This is where the story gets personal.

Where keen instructors were available they began training cadets by wing balancing with the glider mounted on a tripod facing into wind followed by ground slides, then hops, seldom exceeding 20 feet above the ground. One cadet came back from a course at a gliding school where he had qualified with three solo circuits from winch launches to 1000 feet. He was offered a bungee launch in the primary and automatically pulled the stick back, zooming up to a previously unseen height. The instructors were so alarmed that they never used the glider again. CCF primaries soldiered on until the 1980s when they were replaced by flight simulators – not so much fun, but much less effort.

Instructor training, both for the CCF and also for the instructors who flew at the 27 weekend ATC Gliding Schools based at RAF airfields was the responsibility of the two Gliding Centres which were RAF units, part of Home Command. CCF instructor courses were run in the school holidays and included instruction in winch-launched Cadet Mk 3s to solo circuit standard which gave instructors a better perspective on their usual work. This is where the story gets personal.

Back in the 1960s I was on the staff of at No 2 Gliding Centre at RAF Kirton Lindsey in north Lincolnshire. Before this, my only exposure to bungee launching had been at a gliding club on Derbyshire hilltop. A section of dry stone wall had been removed from the crest of the ridge to allow bungee launching when the wind was strong enough. The bungee was laid out in a V shape. At the point of the V was a steel ring, about 2” diameter. When everything was ready, the ring was slipped over on an open hook under the glider’s nose.

The nose of Shuttleworth’s Eton. The front release hook inside

the ring is for winching, the little blade is for the bungee.

The nose of Shuttleworth’s Eton. The front release hook inside

the ring is for winching, the little blade is for the bungee.

The glider had no wheel brake so two hefty chaps went to lie down and grasp the tailskid. The launching crew, about six of us on each end of the V, were told to walk until the bungee tightened – then ‘Run!’. We ran. Being downhill helped. When the tension became too much for the tailskid holders the glider shot smoothly forwards. The bungee contracted and the ring fell off the hook. The runners accelerated almost as quickly as the glider, trying to avoid the occasional stone-in-the-grass which had been thrown downhill when the wall was cleared. There were twelve launches that day and only two people were taken off to hospital with damaged ankles.

The site’s been cleared properly now and you can see a launch from that very place, Camphill.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dyxs51ddWSY

The glider is a Capstan, quite a heavy two-seater, which says something for the power of a bungee.

Launching the CCF’s primary gliders was more carefully controlled. A string with a little wooden ball at the end was tied to the launching ring and ran through little hoops on the bungee to show how much tension was being applied. The launching crew were disciplined. They stretched the bungee by walking until the instructor, watching the little ball on the string told them to stop. Then they turned to face the glider and, more importantly, the bungee. The glider had a release hook at the back of the frame and a cable from there was anchored to the ground. Thus the pilot had the satisfaction of pulling the release himself when he was ready to launch. It took a long time and a lot of effort by many people to get to that point and it says much for the dedication of the instructors and the sustained effort and patience of the cadets.

A launch at The King’s School, Grantham. Note the anchor – a lad with a garden fork.

On one of our instructors’ courses at Kirton Lindsey the power of the bungee was revealed in another way. The short anchor cable was attached to a Land Rover and the first launch of the day was ready to go. The pupils, all CCF officers, pulled out the bungee to full stretch for a high hop, stopped and turned to face the glider. The pilot released and - nothing happened.

Grass has unusual and little-explored characteristics. Usually, it has little stiction and is quite slippery. On that day it held the glider firm. None of the launch crew had ever seen this happen before and began an animated discussion. One or two relaxed their grip on the bungee and it was suddenly pulled out of everyone’s hands and it whipped back towards the glider, the instructor in charge, and me. It came with terrifying speed, like a snake’s strike. Two of us fell to the ground and the loops of bungee whistled over our heads. The strapped-in pilot cowered behind crossed arms. The ends of the bungee slammed into the Land Rover with a noise heard across the airfield, severely dented the mudguard and broke off the wing mirror. A strip of plywood under the glider's skid as a launch pad would have saved our embarrassment and fright.

Research into bungees has shown that the maximum power is reached when the bungee is first stretched. If it is then held, the power slowly deteriorates for several seconds. We carried out some unofficial and probably unwise tests. Making sure that we had no pupils or visitors around we anchored the glider with a weak link in the cable. For the launch crews we used two Land Rovers, driving them at some speed to keep the power going after the weak link had broken. Those launches were truly exhilarating.

Grass has unusual and little-explored characteristics. Usually, it has little stiction and is quite slippery. On that day it held the glider firm. None of the launch crew had ever seen this happen before and began an animated discussion. One or two relaxed their grip on the bungee and it was suddenly pulled out of everyone’s hands and it whipped back towards the glider, the instructor in charge, and me. It came with terrifying speed, like a snake’s strike. Two of us fell to the ground and the loops of bungee whistled over our heads. The strapped-in pilot cowered behind crossed arms. The ends of the bungee slammed into the Land Rover with a noise heard across the airfield, severely dented the mudguard and broke off the wing mirror. A strip of plywood under the glider's skid as a launch pad would have saved our embarrassment and fright.

Research into bungees has shown that the maximum power is reached when the bungee is first stretched. If it is then held, the power slowly deteriorates for several seconds. We carried out some unofficial and probably unwise tests. Making sure that we had no pupils or visitors around we anchored the glider with a weak link in the cable. For the launch crews we used two Land Rovers, driving them at some speed to keep the power going after the weak link had broken. Those launches were truly exhilarating.

Of course, we often launched the Grasshopper by the winch. They say that you don’t suffer from vertigo if you’re not connected to the ground. Well, in a primary the swaying cable is a clear connection. To watch the winch diminishing in size between your boots is a very unsettling feeling.

One of our staff surprised us by taking out the Grasshopper to fly in December. Peter Bullivant was eternally helpful and he’d volunteered to spice up the children’s Christmas Party. He put on his own Father Christmas outfit which he held on tightly with various straps and strings, tied a bag of toys and goodies to the primary and took a winch launch. The children had been told that, although Rudolph was unwell, Father Christmas would get there somehow. After a quick circuit Peter landed to great acclaim outside the cricket pavilion where the party was being held.

Another staff member was an ex-Battle of Britain pilot. Dick’s Hurricane had been shot down during the engagement when Nicholson won his VC. He joked that he still had ‘the twitch’. Certainly, he was not a good glider pilot. He used the stick, not to control it, but to ‘beat it into submission’. Nevertheless, his background, his wings and medal ribbons made him very popular with the cadets. However, he flatly refused to have anything to do with the primary glider. Then we found out why.

When he was first posted to Home Command he was sent out to visit ATC squadrons and CCF units to ‘find out what goes on’. Somewhere in Scotland, he went to a CCF unit and they had their glider rigged. They had quite a small field and had managed slides but had seldom seen it higher than a few inches. Seeing his wings and his moustache they asked him to give them a demonstration. Dick had never set eyes on a primary before but it had a full set of flying controls and was very simple. How difficult could it be? He couldn’t lose face by refusing so he strapped in.

When he was first posted to Home Command he was sent out to visit ATC squadrons and CCF units to ‘find out what goes on’. Somewhere in Scotland, he went to a CCF unit and they had their glider rigged. They had quite a small field and had managed slides but had seldom seen it higher than a few inches. Seeing his wings and his moustache they asked him to give them a demonstration. Dick had never set eyes on a primary before but it had a full set of flying controls and was very simple. How difficult could it be? He couldn’t lose face by refusing so he strapped in.

‘How much pull do you want sir?’ they asked. He mumbled a reply and waved a vague hand. The eager cadets set off at a gallop. The bungee tightened, the little wooden ball which show the amount of stretch slid through its loop and snapped off. Dick fumbled for the release cable beneath his seat. When he found it he was staggered by the acceleration. The glider rose so high that he quickly ran out of space to land and found himself approaching a line of trees. Happily, there was a gap which Dick threaded with a left and right turn. He landed in the next field to the ringing cheers of the delighted cadets. That was the first and last time he sat in a primary.

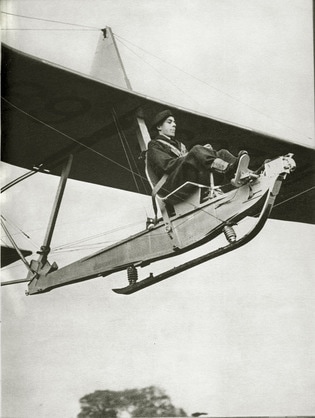

A more normal high hop.

A more normal high hop.

Kirton Lindsey was being handed over to the army so the Gliding Centre had to move. Our new home was RAF Spitalgate, near Grantham. Most of the gliders were to be moved by road in trailers and our fleet of Sedberghs and Cadet Mk 3s went in a succession of convoys. The Grasshopper wouldn’t fit into any trailer. The ‘A’ frame was too tall. And the local Mobile Servicing Party couldn’t help. The boss said ‘The Chipmunk can tow it there. It’s only 40 miles’.

It was October and unusually cold. I drew the short straw. Wearing so many layers of clothing I could hardly climb aboard we set off into quite a brisk headwind. The tow was easy. The Grasshopper has so much drag that the towrope stayed taut. But progress was slow and although we were not much higher than 1000’ the wind at our altitude was too much. After 30 minutes of getting nowhere we turned back for home. My colleagues were adamant. There would be no second draw.

So, a couple of days later, I wrapped up again and we set off in weather which was just as cold, but calmer. We flew along the Roman road towards Lincoln and directly towards Scampton, at the time an active Vulcan base. I had no contact with the Chipmunk pilot, B B Sharman, and was puzzled when he began a gradual descent. He had promised Scampton to show them something they hadn’t seen before and we obliged with a low-level flypast over the tower with much waving and a shout of ‘Good Morning’ from me to offer them a burst of radio-less aircraft/tower communication.

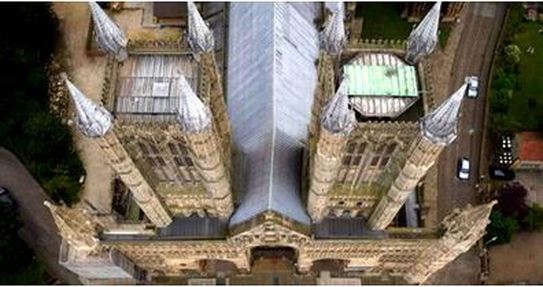

Climbing away to the south we were confronted by Lincoln Cathedral. BB knew that Lincolnshire celebrates its status as the ‘Bomber County’ with a Lancaster fly past over the cathedral and it soon became obvious that he was determined to cement its tenuous relationship with gliders in a similar way.

It was October and unusually cold. I drew the short straw. Wearing so many layers of clothing I could hardly climb aboard we set off into quite a brisk headwind. The tow was easy. The Grasshopper has so much drag that the towrope stayed taut. But progress was slow and although we were not much higher than 1000’ the wind at our altitude was too much. After 30 minutes of getting nowhere we turned back for home. My colleagues were adamant. There would be no second draw.

So, a couple of days later, I wrapped up again and we set off in weather which was just as cold, but calmer. We flew along the Roman road towards Lincoln and directly towards Scampton, at the time an active Vulcan base. I had no contact with the Chipmunk pilot, B B Sharman, and was puzzled when he began a gradual descent. He had promised Scampton to show them something they hadn’t seen before and we obliged with a low-level flypast over the tower with much waving and a shout of ‘Good Morning’ from me to offer them a burst of radio-less aircraft/tower communication.

Climbing away to the south we were confronted by Lincoln Cathedral. BB knew that Lincolnshire celebrates its status as the ‘Bomber County’ with a Lancaster fly past over the cathedral and it soon became obvious that he was determined to cement its tenuous relationship with gliders in a similar way.

The whiff of vertigo returned as the cathedral tower reached up to me and I had an urge to lift up my feet off the rudder pedals. Happily, the feeling and the tower quickly passed and I looked forward to rather less exciting progress to our destination

Not yet. Ahead was Waddington and BB turned a few degrees to port. I didn’t think that was enough to keep out of the way of their Vulcans and I was alarmed to see the runway lights flicker into life. It could only mean that there was a Vulcan on the approach.

Of course, there wasn’t. BB was enjoying himself and had encouraged them to set the scene for another flypast. We cruised past the tower at about 50 feet, this time with flashing Aldis lamps and even a couple of green Very lights. With such an enthusiastic reception I felt embarrassed that I could liven up our stately progress with no more than tame wing waggles and a wave of the hand.

The rest was anti-climax. BB waved me off at 2000 ft over a deserted Spitalgate and I floated down to land by the reception committee of two of our airmen who were waiting to tuck the primary into the back of a hangar. It might have been only 40 miles but BB’s meanderings had extended my ‘primary’ flight time by 1 hr 20 mins.

Not yet. Ahead was Waddington and BB turned a few degrees to port. I didn’t think that was enough to keep out of the way of their Vulcans and I was alarmed to see the runway lights flicker into life. It could only mean that there was a Vulcan on the approach.

Of course, there wasn’t. BB was enjoying himself and had encouraged them to set the scene for another flypast. We cruised past the tower at about 50 feet, this time with flashing Aldis lamps and even a couple of green Very lights. With such an enthusiastic reception I felt embarrassed that I could liven up our stately progress with no more than tame wing waggles and a wave of the hand.

The rest was anti-climax. BB waved me off at 2000 ft over a deserted Spitalgate and I floated down to land by the reception committee of two of our airmen who were waiting to tuck the primary into the back of a hangar. It might have been only 40 miles but BB’s meanderings had extended my ‘primary’ flight time by 1 hr 20 mins.

I logged just one more flight in a primary. The ATC were invited to enter, ‘hors concours’, the National Gliding Championships held at Lasham. We took, not a Sedbergh, but a Skylark (like the one in the picture), a private sailplane belonging to one of the Gliding School COs. The national press were invited. The British Gliding Association hoped that the assembly of dozens of sleek sailplanes, all smooth and polished would generate publicity for the sport.

One of the photographers wandered into the hangar and found a Grasshopper tucked in a corner. It was stored there be a nearby school who used it occasionally. The cameraman was delighted. He saw this as an opportunity to get a truly original angle on his photoshoot and outdo his competitors. As the only people authorised to fly it the RAF contingent were tracked down and persuaded to make a couple of phone calls. We rigged it. One of the really fun things about a Grasshopper is standing on the backrest of the pilot’s seat and turning the big screw on the top of the ‘A’ frame to tighten up the rigging. The primary stretches its wings like an early morning riser and the taut wires can be twanged until they’re in tune.

The photographer gaffer-taped his camera, fitted with a wide-angled lens, to the wing and I was handed a long lead and instructed to take a series of pictures as we flew (on aerotow) over the lines of sailplanes. In the following day’s papers it was one of these shots that got most prominence just because of the primary in the foreground. It was definitely not what the BGA intended.

No-one uses primaries for training any more. But many are preserved and flown purely for the sheer fun they offer. See a bungee launch and some barefoot gliding in Germany in SG-38s here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w9tE-OWyuK0 and also https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h5vtPkB1h3s

During the 2012 Olympics the Gliding Games were staged at Wenlock to remind the Olympic Committee that Germany opted to include gliding in the 1940 games. Naturally, they had to celebrate the SG-38. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Um_kDEy8I20

The photographer gaffer-taped his camera, fitted with a wide-angled lens, to the wing and I was handed a long lead and instructed to take a series of pictures as we flew (on aerotow) over the lines of sailplanes. In the following day’s papers it was one of these shots that got most prominence just because of the primary in the foreground. It was definitely not what the BGA intended.

No-one uses primaries for training any more. But many are preserved and flown purely for the sheer fun they offer. See a bungee launch and some barefoot gliding in Germany in SG-38s here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w9tE-OWyuK0 and also https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h5vtPkB1h3s

During the 2012 Olympics the Gliding Games were staged at Wenlock to remind the Olympic Committee that Germany opted to include gliding in the 1940 games. Naturally, they had to celebrate the SG-38. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Um_kDEy8I20