The Royal Naval Air Service in Belgium (Oct 2019)

On the outbreak of the First World War the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service were separate organisations, both finding their feet and learning to use the aeroplanes and equipment available. The RFC naturally concentrated on the needs of the army and the RNAS maintained its role as the defender of the nation’s shores, for which their seaplanes would be useful. The most threatening aggressor, against which there was no defence, was the Zeppelin and the Navy wasted no time in going into the attack.

Zeppelins were based at a number of bases in north- west Germany. When the Germans implemented the Schlieffen Plan and invaded Belgium the thrust of their attack was to the South West towards Paris. Antwerp and the coastal area were by-passed and, for the time being, left unoccupied. The RNAS took a small force of aeroplanes to Veurne, near Dunkirk. They found an advanced landing ground near Antwerp which they defended with a number of armoured cars. On 22nd August they made history. An Avro 504 of No. 5 Squadron was shot down by German ground fire, the first British aircraft to be destroyed in action in the war.

Zeppelins were based at a number of bases in north- west Germany. When the Germans implemented the Schlieffen Plan and invaded Belgium the thrust of their attack was to the South West towards Paris. Antwerp and the coastal area were by-passed and, for the time being, left unoccupied. The RNAS took a small force of aeroplanes to Veurne, near Dunkirk. They found an advanced landing ground near Antwerp which they defended with a number of armoured cars. On 22nd August they made history. An Avro 504 of No. 5 Squadron was shot down by German ground fire, the first British aircraft to be destroyed in action in the war.

On 22 September, four Sopwith Tabloids, the type which had famously won the 1914 Schneider Trophy as a seaplane 6 months before, took off to attack airship sheds in Cologne and Dusseldorf. They ran into fog and only one pilot found his target. The single 20lb Hales bomb (actually, they contained only 4½ lbs of explosive) which he dropped hit the Dusseldorf shed but failed to explode.

Reggie Marix

Reggie Marix

It wasn’t until 8th October that another raid could be launched. Extra fuel tanks were fitted to two Tabloids and they were topped up at their advanced strip. Squadron Commander Grey was again frustrated by mist over Cologne and dropped his bombs on a railway station. Flt Lt Reggie Marix found the shed at Dusseldorf, dived down from 3000 to 500 feet and, flying through heavy fire from the ground, he planted his bombs on the shed. He was rewarded with the sight of a fireball 500 feet high as Zeppelin LZ25 burst into flame. Marix ran out of fuel 20 miles from his field. A borrowed bicycle and a train ride got him home. The Germans occupied Antwerp the next day and Marix earned the DSO and promotion.

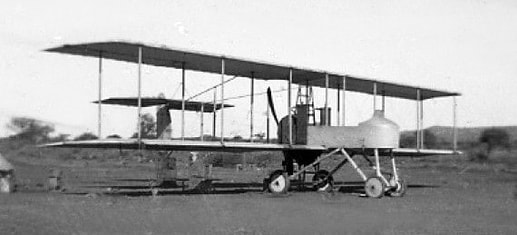

Driven by the First Sea Lord, one Winston Churchill, the Navy’s aggression against the Zepps was not ended. A raid on the home of the Zeppelin, Freidrichshafen, by Lake Constance in southern Germany was planned. Four Avro 504s were ordered from the factory in Manchester and loaded in closed railway wagons with ‘Russian’ markings. They travelled to Belfort in France where the Avros and all of the crews were confined inside a closed hangar. The aircraft emerged on 21st November for their first flight ever. Not knowing how well-trimmed the Avros would be they cleverly attached a bungee cord to each control column so that it could be attached to an appropriate corner of the cockpit if needed to help maintain level flight.

All the engines started and three of the aircraft (the tailskid of the fourth broke off on the rough field) took off for the 125 mile flight to the target. Cruising at 60 mph, they avoided Switzerland and dropped their bombs on the heavily defended site. Sadly, there was no evident damage and one of the Avros was shot down. The other two returned safely.

In December 1918, actually, on Christmas Day, the RNAS carried out a daring and ambitious raid on the Zeppelin base at Cuxhaven, taking nine seaplanes on three converted cross-Channel ferries across the North Sea to within range of the target. They were supported by a fleet of two light cruisers, four destroyers and no fewer than ten submarines. For a variety of reasons, mostly weather related, they achieved little. Four of the seaplanes, but not their crews, were lost and the little fleet returned safely to port having carried out the first bombing raid by ship-borne aircraft.

All the engines started and three of the aircraft (the tailskid of the fourth broke off on the rough field) took off for the 125 mile flight to the target. Cruising at 60 mph, they avoided Switzerland and dropped their bombs on the heavily defended site. Sadly, there was no evident damage and one of the Avros was shot down. The other two returned safely.

In December 1918, actually, on Christmas Day, the RNAS carried out a daring and ambitious raid on the Zeppelin base at Cuxhaven, taking nine seaplanes on three converted cross-Channel ferries across the North Sea to within range of the target. They were supported by a fleet of two light cruisers, four destroyers and no fewer than ten submarines. For a variety of reasons, mostly weather related, they achieved little. Four of the seaplanes, but not their crews, were lost and the little fleet returned safely to port having carried out the first bombing raid by ship-borne aircraft.

In March1915, the RNAS became heavily involved in the Gallipoli campaign and the contingent in Belgium lost No 3 Squadron which was sent off to the Dardenelles. No 1 Squadron remained at Veurne. They extended their remit, unofficially, and indulged in ground warfare, using Rolls Royces converted into armoured cars and raiding the Germans as they tried to establish defences in the boggy countryside.

The Zepps’ usual bases were no longer in easy reach but the airships themselves came into closer range as they flew past Dunkirk on their way home from raids on England. The problem was that the airships operated at night.

The Zepps’ usual bases were no longer in easy reach but the airships themselves came into closer range as they flew past Dunkirk on their way home from raids on England. The problem was that the airships operated at night.

The pilots had to learn a new skill – night flying. They were surprised to find that on most nights there was enough light to be able to fly their aeroplanes safely and they could usually pick out the coastline. But finding their targets was difficult even though airships were very large and flew slowly. On the night of 16/17th May, 1915 they had some help.

Two Zeppelins, LZ38 and LZ39 crossed the coast of Kent on a bombing raid. The defensive guns fired, aimed randomly upwards into the darkness until LZ38 was caught in the beam of the Dover searchlight. It was the first time a searchlight had found a target in the air. Hauptmann Erich Linnarz turned his Zeppelin away and headed for home. Alerted by the guns and the light, six RNAS aeroplanes took off from their fields near Dunkirk. Shortly after crossing the coast, Sub. Lt. Warneford spotted a Zeppelin and climbed in pursuit.

At 5,000 ft he was still 1000ft below LZ-39 – Hauptmann Masius in command. The Avro 504 was rather overloaded with a Lewis gun, several hand grenades and a .45 rifle loaded with some new ‘flaming bullets’. In frustration, the Observer, Sub. Lt Meddis, grabbed the rifle and fired five bullets, ‘at least two’ of which ignited. They had no effect whatever and the Zeppelin climbed away. Warneford vented his fury by diving down over Zeebrugge where he had spotted a U-boat and steamer leaving harbour. They were sprinkled with hand grenades.

Squadron Commander Spenser Grey was next to attack LZ39. Alone in his Nieuport he had reached 9,600 ft and was close to the Zeppelin. He abandoned the idea of dropping hand grenades from above and aimed his Lewis gun at the rear gondola. Four machine guns returned his fire and the airship climbed away from him.

Two Zeppelins, LZ38 and LZ39 crossed the coast of Kent on a bombing raid. The defensive guns fired, aimed randomly upwards into the darkness until LZ38 was caught in the beam of the Dover searchlight. It was the first time a searchlight had found a target in the air. Hauptmann Erich Linnarz turned his Zeppelin away and headed for home. Alerted by the guns and the light, six RNAS aeroplanes took off from their fields near Dunkirk. Shortly after crossing the coast, Sub. Lt. Warneford spotted a Zeppelin and climbed in pursuit.

At 5,000 ft he was still 1000ft below LZ-39 – Hauptmann Masius in command. The Avro 504 was rather overloaded with a Lewis gun, several hand grenades and a .45 rifle loaded with some new ‘flaming bullets’. In frustration, the Observer, Sub. Lt Meddis, grabbed the rifle and fired five bullets, ‘at least two’ of which ignited. They had no effect whatever and the Zeppelin climbed away. Warneford vented his fury by diving down over Zeebrugge where he had spotted a U-boat and steamer leaving harbour. They were sprinkled with hand grenades.

Squadron Commander Spenser Grey was next to attack LZ39. Alone in his Nieuport he had reached 9,600 ft and was close to the Zeppelin. He abandoned the idea of dropping hand grenades from above and aimed his Lewis gun at the rear gondola. Four machine guns returned his fire and the airship climbed away from him.

Waiting even higher was Flight Commander Arthur Bigsworth, his Avro 504 loaded with four 20lbs bombs. He crept behind and 200ft higher than the airship. Then he flew over the ship, placing his bombs at intervals along its length. He turned and flew back alongside the Zeppelin. He had time to see ‘very heavy black pungent smoke’ coming from the ship and noted that it was yawing from side to side. At the time they were over Ostend and suddenly the German guns there opened up an ‘intense fire’, despite the presence of the airship. He flew out to sea, away from the guns and returned to his base to claim a Zeppelin ‘driven down’.

The airship’s crew were lucky. Bigsworth’s bombs had not exploded though they had punctured five of the ship’s 15 gas cells and smashed off the propeller of the starboard aft engine. The smoke probably came from burning oil on the engine. The ship flew on and was witnessed an hour later sagging in to a bad landing at the field at Evere. Ambulances took away the body of a dead officer and some wounded crew members.

The Zeppelin had not been destroyed but this was the first successful attack on an airship, more meritorious in that it was carried out at night and Bigsworth was duly awarded the DSO.

The airship’s crew were lucky. Bigsworth’s bombs had not exploded though they had punctured five of the ship’s 15 gas cells and smashed off the propeller of the starboard aft engine. The smoke probably came from burning oil on the engine. The ship flew on and was witnessed an hour later sagging in to a bad landing at the field at Evere. Ambulances took away the body of a dead officer and some wounded crew members.

The Zeppelin had not been destroyed but this was the first successful attack on an airship, more meritorious in that it was carried out at night and Bigsworth was duly awarded the DSO.

Within minutes, he spotted one at 7,000 ft. over Ostend and set off in pursuit. It took him half an hour to get close enough and he could see that it was painted green on top and yellow underneath. The Zeppelin opened fire with its heavy machine guns. Reggie retreated and the airship turned seemingly to follow him. He escaped by climbing to 11,000 ft. Then he switched off his engine and glided down above the Zeppelin. He released his bombs in sequence and as the last one fell away there was an explosion and the Morane lurched upwards and turned inverted. It took him some time to regain control to look for the airship. He saw it in flames on the ground.

With a stopped engine he could only glide down and find a field to land in. He found that the petrol pipe from the pump was broken and he prepared to set his plane on fire – he was in enemy territory. Then he realised that no one had seen him so he repaired the broken pipe. With some difficulty, he restarted the engine single handed and took off. Not being able to see where he was and flew about until eventually he recognised Cap Gris Nez. He landed near a French army camp where he got some petrol and waited till sunrise. Probably he had breakfast too because he didn’t get back home until 10.30 am.

LZ37 had come down in Sint-Amandsberg, Belgium, killing one person on the ground. All but one of the airship’s crew died. Within 36 hours, Reggie Warneford had been awarded the Victoria Cross – for conspicuous bravery, said the citation, but also because he had shown that the feared Zeppelin was not invulnerable.

Young Warneford was not the most popular man in the squadron – his over confidence and well-polished ego got in the way. Ironically, he didn’t have long to enjoyed his new-found fame. Ten days after his victory over the Zeppelin he received the Légion d'honneur from General Joffre, the French Army C-in-C. After the celebratory lunch he went to the nearby airfield at Buc to collect a new aircraft. He flew a brief test flight then took off again carrying an American journalist. At 200 ft. the right wing collapsed and both men died in the crash.

With a stopped engine he could only glide down and find a field to land in. He found that the petrol pipe from the pump was broken and he prepared to set his plane on fire – he was in enemy territory. Then he realised that no one had seen him so he repaired the broken pipe. With some difficulty, he restarted the engine single handed and took off. Not being able to see where he was and flew about until eventually he recognised Cap Gris Nez. He landed near a French army camp where he got some petrol and waited till sunrise. Probably he had breakfast too because he didn’t get back home until 10.30 am.

LZ37 had come down in Sint-Amandsberg, Belgium, killing one person on the ground. All but one of the airship’s crew died. Within 36 hours, Reggie Warneford had been awarded the Victoria Cross – for conspicuous bravery, said the citation, but also because he had shown that the feared Zeppelin was not invulnerable.

Young Warneford was not the most popular man in the squadron – his over confidence and well-polished ego got in the way. Ironically, he didn’t have long to enjoyed his new-found fame. Ten days after his victory over the Zeppelin he received the Légion d'honneur from General Joffre, the French Army C-in-C. After the celebratory lunch he went to the nearby airfield at Buc to collect a new aircraft. He flew a brief test flight then took off again carrying an American journalist. At 200 ft. the right wing collapsed and both men died in the crash.

In August, Arthur Bigsworth earned another medal, though not involving Zeppelins. On the 26th he was patrolling in a Farman 27 when he spotted a submarine on the surface which he thought was U-14. Ignoring fire from the sub and shore batteries he dived down to 500 ft, approaching several times to get the right line of attack before dropping his bombs.

Two of the 60lb. bombs struck the sub and Bigsworth watched it sinking stern first. Although the Germans denied that any sub was lost that day Bigsworth was awarded a bar to his DSO. (He was also Mentioned in Despatches in June 1918 and is one of the individuals who Capt. W E Johns identified as contributing to the fictitious character of Biggles in his many books).

The RNAS units which had served in Gallipoli came back to Belgium at the end of the campaign and a new No 1 Wing was formed. Initially they flew principally, but not only Nieuport 17 and 21 aircraft. Never feeling any obligation to use the aeroplanes promoted by the Royal Aircraft Factory they were attracted to the new Sopwith fighter, the Triplane, which first flew in June 1916. By the end of the year, all six RNAS squadrons were equipped with the Triplane. It made its mark and not only because of its manœuvrability and rapid rate of climb.

Two of the 60lb. bombs struck the sub and Bigsworth watched it sinking stern first. Although the Germans denied that any sub was lost that day Bigsworth was awarded a bar to his DSO. (He was also Mentioned in Despatches in June 1918 and is one of the individuals who Capt. W E Johns identified as contributing to the fictitious character of Biggles in his many books).

The RNAS units which had served in Gallipoli came back to Belgium at the end of the campaign and a new No 1 Wing was formed. Initially they flew principally, but not only Nieuport 17 and 21 aircraft. Never feeling any obligation to use the aeroplanes promoted by the Royal Aircraft Factory they were attracted to the new Sopwith fighter, the Triplane, which first flew in June 1916. By the end of the year, all six RNAS squadrons were equipped with the Triplane. It made its mark and not only because of its manœuvrability and rapid rate of climb.

B Flight of No 10 Squadron were all Canadian pilots. Their commander, Raymond Collishaw had all their aeroplanes’ cowlings and fins painted black. They all had names – Black Maria, Black Prince, George, Death and Sheep. . . and were flown aggressively. In three months, they had claimed 87 German aircraft.

Such was their reputation with the enemy that there was an outbreak of triplane designs from most of the German manufacturers.

There were problems, of course. It had only one gun, was not happy at high diving speeds, it could have been stronger and was difficult to repair. When the two gun higher powered Camel arrived, the Triplane was phased out.

One of the Camels was involved in a curious incident which is worth recording in some detail. B7184 was built by Clayton and Shuttleworth at Lincoln in December 1917 and was delivered by road. It arrived at No 3 Squadron at Calais on 1th January 1918. Three days later it was one of eight Camels which took off at 2.00 pm on an offensive patrol. When over Houlthulst Wood they encountered seven enemy aeroplanes, four DFW and three ‘scouts, new type’. Flt. Lt. Armstrong attacked and ‘drove down a DFW, out of control’. The other Camels ‘joined in the general engagement and many indecisive combats ensued’. All the enemy aircraft were claimed as being ‘driven down’.

When the flight reassembled Flt. Sub-Lt. Youens was missing. He had last been seen flying west as the flight dived on the enemy. In fact, he had been downed by a Fokker D.VII of Jasta 7, flown by Lt. Carl Degelow. Degelow tells the tale in a book which he wrote after the war - "Germany's Last Knight of the Air". In it he relates that ‘I found myself engaged with a fellow who had caught me by surprise. This pilot, who did not seem too well acquainted with the location of the front lines, belonged, as we later learned, to a group of Dunkirk based fighter pilots who we called the Armstrong Boarding School. Eventually, I forced my opponent to land on our side of the lines, near Dixmude. As was our custom, we sent a car to pick him up and bring him to our airfield, where, in courteous fashion, he could spend the day with us as a guest of honour’.

When the flight reassembled Flt. Sub-Lt. Youens was missing. He had last been seen flying west as the flight dived on the enemy. In fact, he had been downed by a Fokker D.VII of Jasta 7, flown by Lt. Carl Degelow. Degelow tells the tale in a book which he wrote after the war - "Germany's Last Knight of the Air". In it he relates that ‘I found myself engaged with a fellow who had caught me by surprise. This pilot, who did not seem too well acquainted with the location of the front lines, belonged, as we later learned, to a group of Dunkirk based fighter pilots who we called the Armstrong Boarding School. Eventually, I forced my opponent to land on our side of the lines, near Dixmude. As was our custom, we sent a car to pick him up and bring him to our airfield, where, in courteous fashion, he could spend the day with us as a guest of honour’.

The 20 year old Hubert St John Edgerley Youens ‘had his visage temporarily marred by a bloody nose and a lovely pair of swollen black eyes caused by his rough landing’. He was taken to the German mess, which was in a requisitioned castle, Castle Wyengendal, where he was given a meal and wine. Degelow spoke English well and the conversation ‘flowed freely’, lubricated by some shots of whisky. Hubert Youens mentioned that he played the violin. Degelow said that they had a piano, but no violin. The cook overheard this conversation and came in to say that one of the officers had brought back a violin from his last leave. It was produced, but had a string missing. ‘Never mind’, said Youens and he pulled out two complete sets of new strings from his pocket. Properly tuned up and with Degelow on the piano they started by playing the German national anthem. They were both competent musicians and many other tunes followed. Finally, they played ‘God Save the King’ and ‘every German in the room stood at respectful attention as a sign of comradeship beyond the bounds of national or political affiliation’.

The following morning, Youens was given an overcoat and before being taken off to a PoW camp he was included in a group photograph. Here he is, marked with a cross. Degelow, with a stick, stands next to him. (Carl Degelow was credited with 39 victories and was the last airman to be awarded the Pour Le Merite in January 1918).

The Jasta’s record book includes the entry ’A double victory, on the one hand the hard-fought air battle that ended victoriously; and, on the other hand, the musical pleasure that the loser so bountifully and cordially provided us.’

Kissenberth was unusual in that he always wore spectacles when flying but he was an accomplished pilot with 18 victories and skilful enough to master the Camel’s eccentricities. He had it repainted with his Jasta’s white tail and fuselage bar and the regulation Balkenkreuz. The RNAS eagle was not painted over. On 18th May Otto used the Camel to shoot down an SE 5a (with, no doubt, a surprised pilot - Lt S B Reece of 64 Sqn). On 29th May, the Camel’s engine failed shortly after take-off and the injuries Kissenberth suffered in the crash ended his flying career.

Hubert Youens was incarcerated in the notorious Holzminden prison camp, run by Hauptmann Karl Niemeyer and generally rated as the worst PoW camp in Germany because of his harsh and punitive regime. It was the site of WWI’s ‘Great Escape’. A tunnel was dug and 86 officers were ready to escape on the night of 24th July, 1918. 29 got out before the tunnel collapsed and 10 of those succeeded in making their way home via neutral Holland. In the picture below, Hubert Youens, who was not a potential escapee, is on the extreme right. He came home at the end of the war in December 1918.

In the late 80s a letter filtered through to Hubert Youens. Dated September 1970 it had been sent to the Services Liaison Officer at the British Consulate asking if Flt Lt Hubert Youens RNAS could be traced and given an invitation to the 80th birthday party of Carl Degelow on 5th January 1971. Hubert would have been delighted to have gone to round off an interesting story.

In the event, the party was never held. Carl Degelow died in November 1970.

In the event, the party was never held. Carl Degelow died in November 1970.