Recent Newsletters have featured rather a lot of trans-ocean flying. Here’s another - well, a trans-sea crossing - which was the vital part of a quite extra-ordinary story. I was told that, in 1940, two Danes had escaped from Denmark by flying a Hornet Moth across the North Sea to England. The Hornet hadn’t the range to complete the flight so they took several cans of fuel in the cabin and, mid-flight, one of them climbed out onto the wing and topped up the tank. Researching the practicalities of this needed a visit to the De Havilland Museum to examine their Hornet Moth. More digging elsewhere unearthed the full story.

Hornet Moth to Freedom [May 2022]

In April 1940, Europe had been at war for seven months, though there was little fighting going on. Germany had absorbed Austria, invaded Czechoslovakia and overrun Poland but the Danes didn’t expect to get involved. Hitler had signed a non-aggression pact with Denmark on 31st May 1939 and their country was of no strategic importance to Germany.

But Norway was. Occupation of Norway would give the German Navy and U-boats easy access to the Atlantic and would secure the essential supplies of Swedish steel that were shipped to Germany via the Norwegian port of Narvik. Hitler disregarded his treaty and his armoured cars drove across the Danish border at 4.15 am on 9th April. German para-troops landed on the airfields in North Denmark and a fleet of troopships and escorting warships sailed through Danish waters on their way to Norway. The Danish defences were taken by surprise. One fort was manned by two privates (armed with one old rifle and no ammunition) and a civilian caretaker. There were some pockets of token resistance but nowhere were they effective.

But Norway was. Occupation of Norway would give the German Navy and U-boats easy access to the Atlantic and would secure the essential supplies of Swedish steel that were shipped to Germany via the Norwegian port of Narvik. Hitler disregarded his treaty and his armoured cars drove across the Danish border at 4.15 am on 9th April. German para-troops landed on the airfields in North Denmark and a fleet of troopships and escorting warships sailed through Danish waters on their way to Norway. The Danish defences were taken by surprise. One fort was manned by two privates (armed with one old rifle and no ammunition) and a civilian caretaker. There were some pockets of token resistance but nowhere were they effective.

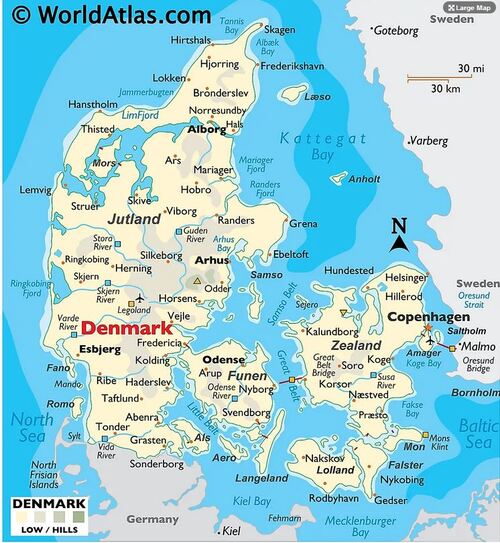

The Germans deliberately adopted a light touch as occupiers of Denmark. Servicemen were allowed to return to their units and wear their uniforms although they had no longer had any function. They effectively became reservists, living at home and expecting never to be called up. Thomas Sneum went to his home on the little island of Fanø, a 10 minute ferry ride from the port of Esbjerg on the west coast of Jutland.

The senior German officer on the island, Hauptmann Meinecke, was a friendly, middle-aged officer and displayed no fervour for Nazi-ism. He passed on a message to Sneum; Goering was inviting him to join the Luftwaffe. Two years previously, Goering had paid an official visit to Denmark’s Army and Navy and Thomas had been assigned to him as interpreter. Obviously he had made a good impression on Goering.

Thomas was taken on a tour of some airfields in Germany. He half considered the offer, seeing it as an opportunity to collect much information about the Luftwaffe, then defecting to England to pass it on. He realised that, with a background like that he would never be trusted. He refused the offer and returned to Fanø to pursue another project.

In his walks around the island he had seen in the distance an odd looking building which the Germans had put up on the sand dunes on the coast facing the North Sea. Even with his binoculars he couldn’t make out what it was. He couldn’t get closer because his view was blocked by the forest of pine trees and, more significantly, snaking through the woods was a perimeter fence patrolled by armed guards and dogs. He wanted to find out more about it - that was the sort of information that would really interest the British. He met Meinecke again, a meeting which turned into a friendly chat over a drink or two. He cultivated this ‘friendship’ and had drinks with other German officers in the hotel which they had taken over as an officers’ mess. He learned nothing about the hut with a grid on its roof; the Germans involved with it seemed to keep within their own isolated enclave.

Thomas was taken on a tour of some airfields in Germany. He half considered the offer, seeing it as an opportunity to collect much information about the Luftwaffe, then defecting to England to pass it on. He realised that, with a background like that he would never be trusted. He refused the offer and returned to Fanø to pursue another project.

In his walks around the island he had seen in the distance an odd looking building which the Germans had put up on the sand dunes on the coast facing the North Sea. Even with his binoculars he couldn’t make out what it was. He couldn’t get closer because his view was blocked by the forest of pine trees and, more significantly, snaking through the woods was a perimeter fence patrolled by armed guards and dogs. He wanted to find out more about it - that was the sort of information that would really interest the British. He met Meinecke again, a meeting which turned into a friendly chat over a drink or two. He cultivated this ‘friendship’ and had drinks with other German officers in the hotel which they had taken over as an officers’ mess. He learned nothing about the hut with a grid on its roof; the Germans involved with it seemed to keep within their own isolated enclave.

He worked out a plan, fraught with risk. Taking his hunting rifle - and shooting a rabbit on the way to strengthen his cover story, he found a place in the woods where he could get though the fence. He was making good progress when suddenly he was confronted by a snarling Alsation. It was not on a lead and there was no sign of the guard. The dog leapt at Thomas and he instinctively raised his gun and fired. The guard appeared, furious that his dog had been killed. Thomas was taken at bayonet point into a guard hut where there was some discussion about just shooting him now. He retaliated. ‘Hauptmann Meinecke is a friend of mine and I’m going to report you for not having your dog under control’. Unbelievably, they simply took his name and address and warned him to keep away from the guarded part of the island.

Although Meinecke was rather cooler the next time he met him, Sneum continued plying his German ‘friends’ with drinks. In a discussion about whether the British would invade Denmark one boasted ‘They would never get away with it - we have new technology. We would see their ships coming - aircraft as well’. Sneum knew nothing about radar but was sure the German has been referring to that strange hut. (It was, of course, one of the first installations of the Freya radar system, the equivalent of the British Chain Home).

Sneum wrote a report, particularly about the hut, but also everything he had learned about the German military installations in Denmark and put it in a sealed envelope. He asked a friend, who travelled to and from Sweden on business, to post it there to the British Embassy in Stockholm. The outcome was an invitation to visit the Embassy. He found this surprisingly easy. There seemed to be little security on the short ferry crossing and no-one checked his luggage in which there was a hidden updated report - the Germans had added two more buildings to the site on the coast.

Thomas was received by Captain Henry Denham, the Naval Attaché. He listened politely to Thomas’s proposal to assemble a group of young Danes by a lake in central Denmark. His plan was they would be picked up by a Sunderland flying boat and taken to England where they would join the RN and RAF. Denham was more interested in the strange huts. Sneum’s report was the first the British had heard about German radar. They wanted to know more - and the best person to get it was Thomas. He was given a small Leica 35mm camera and, for good measure, a Movikon film camera and asked to take as many pictures as he could.

Thomas travelled back to the ferry in a mixture of emotions - frustrated by not being able to escape to England but highly motivated by the challenge he had been set. He was wearing his uniform which, for winter wear, was covered not by an overcoat, but by a heavy shapeless cloak, very convenient for covering his cameras. The ferry was about to leave when he had an extra-ordinary stroke of luck. A lorry rushed up and the dockside crane lifted off a large crate. It was dropped awkwardly on the deck and a door in the side of the crate swung open. It looked like a control cabin just like those he had seen on the site at Fanø. Thomas got out his Leica and was able to take three pictures before the door was closed.

Back at home on the island the next step would not be so easy. Using the shotgun and dead rabbits cover again he stayed outside the fence to avoid meeting the guards. He moved along the fence to the point where it was nearest to the strange hut and took more photographs through gaps in the trees. He noticed, for the first time, that the whole unit occasionally rotated slowly. He also studied and timed the guard’s movements. When he took the movie camera he enlisted the help of a friend to act as look out. They rode out through the woods on their bicycles. Sneum was well aware that if he was caught near this secret installation with a movie camera he would inevitably be shot. They got in position and crouched down by the fence, waiting for the aerial to begin to move.

The camera whirred but not very loudly. Then there was a rustling noise from his friend. He said ‘There’s somebody coming’. He ran for his bicycle and pedalled off. Thomas tucked the camera inside his jacket and hurriedly pulled down his trousers and squatted down. A guard came up, rifle at the ready. ‘What are you doing?’ he shouted. ‘What do you think?’, said Thomas. ‘Oh’. The guard seemed embarrassed and shuffled off. Thomas could hardly believe how he had escaped detection.

A few days later he summoned up enough courage to go back to the radar station, this time in the darkness before sunrise. He carried his shotgun as usual and his cameras were in his pack, hidden under the duck he had shot the day before. He got across the fence and headed for a water tower that was about 50 meters from the radar hut. The guards had put a platform on top of it and built a sort of parapet round it. They were using it as a lookout point. It was not far from the trees and Thomas had worked out that if he could get across the gap to the water tower unnoticed he would be under the parapet and out of the guards’ sight.

It had taken longer than he expected to get past the fence guards and through the woods. The sun had risen before he reached the open space between the trees and the tower. He was close enough to hear the guards chatting to each other. Then their voices raised. They all seemed to be looking for something out to sea. He seized the opportunity and ran quietly to the tower. With the Leica he took a few close-up pictures of the hut and its aerial. Then the aerial began to move. The whirring of the movie camera blended with the sound of the electric motor turning the aerial as it tracked the distant aeroplane that the guards were following with their binoculars. The aeroplane turned and flew back on the reverse track. It seemed that the radar was being calibrated.

Thomas’s amazing luck continued, The whole sequence was recorded on film, the aeroplane still had the guards’ attention and Thomas melted back into the woods.

Overwhelmed with his success in getting close up pictures and film he turned to how he was going to get the films to England. The reels were bulky and couldn’t be hidden easily in luggage. Checks on the ferry had become more rigorous and he couldn’t ask anyone else to take the risk of carrying them to Sweden. He began to suspect that he was being watched and constantly checked to see if anyone was following him. His scheme of being picked up by Sunderland was never going to happen. But he was a pilot. He didn’t need another pilot to take him to Britain. All he needed was an aeroplane - and all Danish civilian aeroplanes had been grounded. Grounded but not destroyed. They must be tucked away in hangars or sheds somewhere. Several De Havilland aeroplanes had been sold in Denmark before the war and they had a representative in Copenhagen. Perhaps he could help.

Thomas travelled to Copenhagen. He rang the agent but he was suspicious and unhelpful. It sounded as though he believed his telephone was being tapped. Thomas went round to his office. Even off the telephone, the agent’s attitude was unchanged. He suspected he was being tricked. On his way out, Thomas noticed a manual on a desk In the outer office. He flicked over the pages. It was a complete listing of all the DH aeroplanes in Denmark, their bases and names and addresses of their owners. He tucked it inside his coat.

Thomas contacted a friend, Kjeld Petersen, who had been an engineer and had qualified as a pilot just before the Germans invaded. He would be an ideal companion if the plan worked out. They studied the book together. Petersen found a Hornet Moth he knew a little about. It had been used by a photographer to take and sell pictures of country houses and estates. It was now registered to a Poul Andersen who ran a dairy farm near Odense.

Thomas went to see him. His cover story was that he was looking for an old aeroplane that he could service and fly after the war. Andersen was firm - he didn’t want to sell his plane. Thomas took a risk. ‘What if I told you that the plane would be going West?’. The reply came immediately. ‘Then it’s yours - no charge’. He took Thomas to a barn and unlocked the door. Even in the gloomy light Thomas could see that the old Hornet Moth was very shabby. The wings were off and stacked by the rear wall. The plane had been dismantled at Kastrup when the Germans arrived. Andersen rattled a linen bag. ‘All the bolts are in here. And in that crate is the fin and rudder, It was damaged in the move but it’s been repaired’. Andersen stressed that the engine was in good condition and had recently been serviced. Because the range was only 600 kilometres, it was not enough to reach England in one hop, Andersen pointed out two full fuel drums and told Thomas he could take as much as he wanted. He stressed that Thomas must fake a break in when he took the plane and, most importantly, warn Andersen when he was about to leave so that the farmer and his family could go away to show they were not involved in the affair.

Sneum wrote a report, particularly about the hut, but also everything he had learned about the German military installations in Denmark and put it in a sealed envelope. He asked a friend, who travelled to and from Sweden on business, to post it there to the British Embassy in Stockholm. The outcome was an invitation to visit the Embassy. He found this surprisingly easy. There seemed to be little security on the short ferry crossing and no-one checked his luggage in which there was a hidden updated report - the Germans had added two more buildings to the site on the coast.

Thomas was received by Captain Henry Denham, the Naval Attaché. He listened politely to Thomas’s proposal to assemble a group of young Danes by a lake in central Denmark. His plan was they would be picked up by a Sunderland flying boat and taken to England where they would join the RN and RAF. Denham was more interested in the strange huts. Sneum’s report was the first the British had heard about German radar. They wanted to know more - and the best person to get it was Thomas. He was given a small Leica 35mm camera and, for good measure, a Movikon film camera and asked to take as many pictures as he could.

Thomas travelled back to the ferry in a mixture of emotions - frustrated by not being able to escape to England but highly motivated by the challenge he had been set. He was wearing his uniform which, for winter wear, was covered not by an overcoat, but by a heavy shapeless cloak, very convenient for covering his cameras. The ferry was about to leave when he had an extra-ordinary stroke of luck. A lorry rushed up and the dockside crane lifted off a large crate. It was dropped awkwardly on the deck and a door in the side of the crate swung open. It looked like a control cabin just like those he had seen on the site at Fanø. Thomas got out his Leica and was able to take three pictures before the door was closed.

Back at home on the island the next step would not be so easy. Using the shotgun and dead rabbits cover again he stayed outside the fence to avoid meeting the guards. He moved along the fence to the point where it was nearest to the strange hut and took more photographs through gaps in the trees. He noticed, for the first time, that the whole unit occasionally rotated slowly. He also studied and timed the guard’s movements. When he took the movie camera he enlisted the help of a friend to act as look out. They rode out through the woods on their bicycles. Sneum was well aware that if he was caught near this secret installation with a movie camera he would inevitably be shot. They got in position and crouched down by the fence, waiting for the aerial to begin to move.

The camera whirred but not very loudly. Then there was a rustling noise from his friend. He said ‘There’s somebody coming’. He ran for his bicycle and pedalled off. Thomas tucked the camera inside his jacket and hurriedly pulled down his trousers and squatted down. A guard came up, rifle at the ready. ‘What are you doing?’ he shouted. ‘What do you think?’, said Thomas. ‘Oh’. The guard seemed embarrassed and shuffled off. Thomas could hardly believe how he had escaped detection.

A few days later he summoned up enough courage to go back to the radar station, this time in the darkness before sunrise. He carried his shotgun as usual and his cameras were in his pack, hidden under the duck he had shot the day before. He got across the fence and headed for a water tower that was about 50 meters from the radar hut. The guards had put a platform on top of it and built a sort of parapet round it. They were using it as a lookout point. It was not far from the trees and Thomas had worked out that if he could get across the gap to the water tower unnoticed he would be under the parapet and out of the guards’ sight.

It had taken longer than he expected to get past the fence guards and through the woods. The sun had risen before he reached the open space between the trees and the tower. He was close enough to hear the guards chatting to each other. Then their voices raised. They all seemed to be looking for something out to sea. He seized the opportunity and ran quietly to the tower. With the Leica he took a few close-up pictures of the hut and its aerial. Then the aerial began to move. The whirring of the movie camera blended with the sound of the electric motor turning the aerial as it tracked the distant aeroplane that the guards were following with their binoculars. The aeroplane turned and flew back on the reverse track. It seemed that the radar was being calibrated.

Thomas’s amazing luck continued, The whole sequence was recorded on film, the aeroplane still had the guards’ attention and Thomas melted back into the woods.

Overwhelmed with his success in getting close up pictures and film he turned to how he was going to get the films to England. The reels were bulky and couldn’t be hidden easily in luggage. Checks on the ferry had become more rigorous and he couldn’t ask anyone else to take the risk of carrying them to Sweden. He began to suspect that he was being watched and constantly checked to see if anyone was following him. His scheme of being picked up by Sunderland was never going to happen. But he was a pilot. He didn’t need another pilot to take him to Britain. All he needed was an aeroplane - and all Danish civilian aeroplanes had been grounded. Grounded but not destroyed. They must be tucked away in hangars or sheds somewhere. Several De Havilland aeroplanes had been sold in Denmark before the war and they had a representative in Copenhagen. Perhaps he could help.

Thomas travelled to Copenhagen. He rang the agent but he was suspicious and unhelpful. It sounded as though he believed his telephone was being tapped. Thomas went round to his office. Even off the telephone, the agent’s attitude was unchanged. He suspected he was being tricked. On his way out, Thomas noticed a manual on a desk In the outer office. He flicked over the pages. It was a complete listing of all the DH aeroplanes in Denmark, their bases and names and addresses of their owners. He tucked it inside his coat.

Thomas contacted a friend, Kjeld Petersen, who had been an engineer and had qualified as a pilot just before the Germans invaded. He would be an ideal companion if the plan worked out. They studied the book together. Petersen found a Hornet Moth he knew a little about. It had been used by a photographer to take and sell pictures of country houses and estates. It was now registered to a Poul Andersen who ran a dairy farm near Odense.

Thomas went to see him. His cover story was that he was looking for an old aeroplane that he could service and fly after the war. Andersen was firm - he didn’t want to sell his plane. Thomas took a risk. ‘What if I told you that the plane would be going West?’. The reply came immediately. ‘Then it’s yours - no charge’. He took Thomas to a barn and unlocked the door. Even in the gloomy light Thomas could see that the old Hornet Moth was very shabby. The wings were off and stacked by the rear wall. The plane had been dismantled at Kastrup when the Germans arrived. Andersen rattled a linen bag. ‘All the bolts are in here. And in that crate is the fin and rudder, It was damaged in the move but it’s been repaired’. Andersen stressed that the engine was in good condition and had recently been serviced. Because the range was only 600 kilometres, it was not enough to reach England in one hop, Andersen pointed out two full fuel drums and told Thomas he could take as much as he wanted. He stressed that Thomas must fake a break in when he took the plane and, most importantly, warn Andersen when he was about to leave so that the farmer and his family could go away to show they were not involved in the affair.

A couple of days later Sneum and Petersen took the tram to the outskirts of Odense and walked across the fields to reach the barn. They swept the dirt off the Hornet Moth and were reassured that it seemed be in reasonable condition. But they were alarmed to find that the bag of bolts must have been for another aeroplane. None of them fitted. They would have to get some made - and who would have access to the hardened molybdenum steel?. They took careful measurements. They were relieved to find that the largest bolts which locked the wings in position were still in place in the wings

They checked to see how Sneum’s plan to refuel in mid-air would work. The Hornet Moth is a 4-seat aeroplane. Two (tightly-packed) passengers sit behind the pilots and the fuel tank is under that rear seat. Its filler cap is behind a small flap just behind the door. So anyone standing on the strengthened ‘Walk Here’ panel on the wing would have easy access to the filler cap - whilst holding on with one hand and preventing too much fuel being blown away by the slipstream . . Plan B emerged. The wing walker would just insert a tube which was pulled out through a hole in the rear window. At the other end of the tube there would be a wide funnel and refuelling would be an easy inside job.

It took some time to find an engineering firm that could make those special bolts. They also made a number of fuel cans of the right shape and size to be manoeuvred in the confined space of the Moth’s rear ‘cabin’. Getting the Hornet ready for the flight was a major operation. Holger Petersen recruited four engineers who had served with him in the army. They could work only at night; during the day the farm workers were passing to and fro past the barn. It took more than one trip to the barn, travelling in ones and twos and carrying, as unobtrusively as possible all the tools and fittings they needed, including a number of lights and some rolls of sacking to hang round the walls to black out the barn. Finally, all the work was done and, with a final check on the weather forecast, they were able to schedule the night to leave. Andersen was warned and he and his family went away to visit relatives.

There was a railway near the farm and goods trains rattled by during the night. They timed the trains and worked out how much time they had for the trains to cover the noise of the engine. The wings were fitted to the fuselage but the Hornet Moth had to be pulled out of the barn before the wings could be spread. It jammed in the door. They took the barn doors off and chopped away the door frame with axes. Even so, with the last heave a jagged piece of wood ripped the fabric of one of the wings. They laced it together with bits of wire. The delay meant they had missed their train. They had to wait half an hour for the next one.

Everything was checked again. The cases containing the film, photographs and sheaf of notes on German dispositions, equipment and armament, the stowed tins of fuel, the refuelling tube and funnel and the last piece of equipment, a 2 metre long pole which they would push through a hole they had drilled in the transparent plastic cabin roof, if they needed it. On the pole Sneum had nailed a white flag, actually a large bath towel. If they were detected by the Germans’ new technology, this sign of surrender might save them from being shot down by fighters.

One of the engineers repeatedly turned over the engine by hand to get the oil circulating. The chuffing goods train and rattling trucks approached. ‘Contact’ yelled Sneum. The engine burst into life. It was more than a year since it had last run yet it sounded fine. Sneum had to taxi more than 200 metres across a turnip field to reach the open pasture that they would use as a runway. Petersen ran ahead with a small torch to guide Sneum away from patches of rough ground. The engine was thoroughly warm when they reached the large field. Petersen climbed aboard, banging into the flagpole which cracked the roof. There was little wind and the field sloped gently downhill, giving much needed help to the grossly overloaded Hornet Moth.

The take off seemed to go on for ever and ahead of them was a line of power cables. The Moth staggered into the air - and sank down to the ground. Another hop, then a third and this time it was really flying. There was no question of clearing the cables. Sneum held the Moth down and flew underneath the wires. Then he had to climb to get over the railway embankment. But now, at last, they were on their way.

There was a railway near the farm and goods trains rattled by during the night. They timed the trains and worked out how much time they had for the trains to cover the noise of the engine. The wings were fitted to the fuselage but the Hornet Moth had to be pulled out of the barn before the wings could be spread. It jammed in the door. They took the barn doors off and chopped away the door frame with axes. Even so, with the last heave a jagged piece of wood ripped the fabric of one of the wings. They laced it together with bits of wire. The delay meant they had missed their train. They had to wait half an hour for the next one.

Everything was checked again. The cases containing the film, photographs and sheaf of notes on German dispositions, equipment and armament, the stowed tins of fuel, the refuelling tube and funnel and the last piece of equipment, a 2 metre long pole which they would push through a hole they had drilled in the transparent plastic cabin roof, if they needed it. On the pole Sneum had nailed a white flag, actually a large bath towel. If they were detected by the Germans’ new technology, this sign of surrender might save them from being shot down by fighters.

One of the engineers repeatedly turned over the engine by hand to get the oil circulating. The chuffing goods train and rattling trucks approached. ‘Contact’ yelled Sneum. The engine burst into life. It was more than a year since it had last run yet it sounded fine. Sneum had to taxi more than 200 metres across a turnip field to reach the open pasture that they would use as a runway. Petersen ran ahead with a small torch to guide Sneum away from patches of rough ground. The engine was thoroughly warm when they reached the large field. Petersen climbed aboard, banging into the flagpole which cracked the roof. There was little wind and the field sloped gently downhill, giving much needed help to the grossly overloaded Hornet Moth.

The take off seemed to go on for ever and ahead of them was a line of power cables. The Moth staggered into the air - and sank down to the ground. Another hop, then a third and this time it was really flying. There was no question of clearing the cables. Sneum held the Moth down and flew underneath the wires. Then he had to climb to get over the railway embankment. But now, at last, they were on their way.

They flew parallel to the railway line and checked to see what the compass showed. A study of a map had given them the railway’s direction and the compass disagreed by 30°. Trying other directions seemed to produce the same result. So the course to England would have to be West plus 30°.

Thomas didn’t feel that the Hornet was flying right. The left wing seemed to be heavier than the right. Had they rigged it properly? If Thomas had been given a proper briefing before flying the Hornet Moth he would have learned that all pilots new to the Hornet felt this way. Sitting on one side of the centre line, nothing in his view of the tapering nose is pointing in the direction of flight. And that Y shaped control column doesn’t help. When the stick is moved to the right it goes up. New pilots are recommended to do their first flights with minimum fuel loads. At heavier weights, the handling gets ‘more demanding’. With all that fuel on the rear seat it was almost certain that the CG was out of limits. The overloaded Moth and struggling pilot climbed slowly to 5,000 feet.

Thomas didn’t feel that the Hornet was flying right. The left wing seemed to be heavier than the right. Had they rigged it properly? If Thomas had been given a proper briefing before flying the Hornet Moth he would have learned that all pilots new to the Hornet felt this way. Sitting on one side of the centre line, nothing in his view of the tapering nose is pointing in the direction of flight. And that Y shaped control column doesn’t help. When the stick is moved to the right it goes up. New pilots are recommended to do their first flights with minimum fuel loads. At heavier weights, the handling gets ‘more demanding’. With all that fuel on the rear seat it was almost certain that the CG was out of limits. The overloaded Moth and struggling pilot climbed slowly to 5,000 feet.

They headed roughly west, occasionally flying through cloud and relieved to find that all the instruments were working properly. Blind flying was not a problem. Thomas changed course every few minutes. He was sure they were being tracked. He was aiming to cross the Danish coast close to the German border where he thought that there would be fewer anti-aircraft guns. He got it wrong and they popped out of cloud over Esbjerg, the most heavily defended port on the west coast. The barrage opened up and they weaved through a sky peppered with black shell bursts. Thomas could see the flashes of the guns, Ironically, some were based near his home on the island of Fanø. He twisted and turned and dived to escape out over the dark sea.

[It was later that they learned that their wandering flight could well have been challenged. However, just days earlier most of the Luftwaffe units based in Denmark had been moved to Poland. Three hours after the Hornet Moth’s midnight take off German forces attacked the Russians. Operation Barbarossa began on 22 June 1941].

Climbing steadily they were at 6,000 ft before they cleared the cloud and stars appeared. There was Polaris, where they hoped to find it, above the starboard wingtip. They were on the right course, heading West with the compass reading 300°. They had almost relaxed in the steady comfortable cruise when the engine coughed. It continued to run, but roughly. Petersen noticed the oil pressure gauge was flickering at a very low reading. Sneum closed the throttle and lowered the nose. If the engine was losing oil it would soon seize up. Ditching seemed inevitable and there was no hope of rescue. The two friends said ‘Good-bye’ to each other. As they neared the waves Sneum tried to make the ditching as gentle as possible and opened the throttle to raise the nose and fly slowly. The engine roared into life and after a couple of coughs ran normally. Although they couldn’t work out what had happened they decided that the engine didn’t like high altitudes and they determined to fly no higher than 2000ft. (In discussion afterwards they realised it must have been carburettor icing which caused the problem).

Soon it was time to refuel. Petersen took control. He reduced the throttle to slow the aeroplane so that Thomas could force open his door. He had practised this on the ground but it was entirely different in the dark with the slipstream jamming the open door against his left hand which was gripping the door frame. With the hose wrapped around his right arm he found it difficult to get a grip on the filler cap with his frozen fingers. When he did get the cap off he had to feed the flapping hose into the tank at exactly the right angle. As he pushed the door open to climb back in his foot slipped off the wing and he was left hanging on with only his left hand. When he finally fell back in his seat he was exhausted.

Petersen dug out the only food they had brought with them, a packet of biscuits and a small bottle of grape juice. They helped Thomas to recover sufficiently to take over the controls. Then he held the refuelling tube with one hand while Petersen, kneeling on his seat, put in the funnel and opened the first can of petrol. The slipstream swirling in through the broken windows blew petrol everywhere. More was spilled with every bump of the Hornet Moth. Soon both men were soaked in petrol and getting colder and colder as it evaporated. They were affected worst by the fumes which quickly became unbearable. They had to stop pouring petrol to be able to breathe. As much petrol was wasted as went into the tank. The process went on for forty five minutes, pouring, retching, recovering.

The sun had risen behind them when they saw the Northumberland coast ahead. They had confirmation that it was England when Petersen pointed out a formation of four Hurricanes overhead. They had been detected by radar and plotted by the Observer Corps. Thomas checked to see if his white flag was still there. It was though all but the last six inches had blown away. A Spitfire flew past them alongside, the pilot pointing downwards. Thomas rejected the first field that looked suitable. There were sheep in it - and telephone wires. The next field was fine and the Hornet Moth rumbled to a stop alongside a gate leading to a road alongside. It was 5.30 am on 22nd June 1941.

The two weary pilots pulled off their petrol soaked overalls. They opened the case in which they had brought fresh white shirts and ties and their uniforms. The first person they met was a farm worker. He refused to tell them where they were. Didn’t they know there was a war on?

Soon two trucks arrived, each with an officer and a driver, both armed. The Danes were taken to nearby RAF Acklington where no-one seemed to believe their story. Nevertheless, they were given breakfast, then taken to the sick bay where they were invited to sleep till lunchtime. More interrogations followed, copious notes were taken and Thomas handed over his precious parcel of films.

This story has been about the remarkable flight of Thomas Sneum and Kjeld Petersen across the North Sea but it can’t be left without covering some of the aftermath.

What happened to the films is covered by R V Jones in his book ‘Most Secret War’. The undeveloped films reached MI5 and were given to the Post Office for processing. It all went badly wrong and the films were ruined. Just one or two frames showed anything useful. Sneum was furious but agreed to be parachuted back into Denmark to work for MI5. There were other agents in Denmark but they worked with SOE, the Special Operations Executive which was charged by Churchill to ‘set Europe ablaze’. Incredibly MI5 and SOE worked entirely independently of each other, resented each other’s presence and even worked against each other. Sneum’s mission in Denmark was a failure and he escaped to Sweden by walking across the frozen sea. When he got to England he spent some time in Brixton Prison (at the instigation of SOE) but was released and joined the RAF. He flew in a Mosquito squadron and R V Jones persuaded the RAF to let him lead his squadron into Copenhagen Airport on the liberation of Denmark at the end of the war.

Kjeld Petersen flew Spitfires in the RAF and after the war rose to the rank of Lt. Colonel in the Danish Air Force.

Poul Andersen never got his Hornet Moth back but he did get away with any involvement with its flight to England.

The Broomstick and what was left of the towel hung on a wall in RAF Acklington for many years.

[It was later that they learned that their wandering flight could well have been challenged. However, just days earlier most of the Luftwaffe units based in Denmark had been moved to Poland. Three hours after the Hornet Moth’s midnight take off German forces attacked the Russians. Operation Barbarossa began on 22 June 1941].

Climbing steadily they were at 6,000 ft before they cleared the cloud and stars appeared. There was Polaris, where they hoped to find it, above the starboard wingtip. They were on the right course, heading West with the compass reading 300°. They had almost relaxed in the steady comfortable cruise when the engine coughed. It continued to run, but roughly. Petersen noticed the oil pressure gauge was flickering at a very low reading. Sneum closed the throttle and lowered the nose. If the engine was losing oil it would soon seize up. Ditching seemed inevitable and there was no hope of rescue. The two friends said ‘Good-bye’ to each other. As they neared the waves Sneum tried to make the ditching as gentle as possible and opened the throttle to raise the nose and fly slowly. The engine roared into life and after a couple of coughs ran normally. Although they couldn’t work out what had happened they decided that the engine didn’t like high altitudes and they determined to fly no higher than 2000ft. (In discussion afterwards they realised it must have been carburettor icing which caused the problem).

Soon it was time to refuel. Petersen took control. He reduced the throttle to slow the aeroplane so that Thomas could force open his door. He had practised this on the ground but it was entirely different in the dark with the slipstream jamming the open door against his left hand which was gripping the door frame. With the hose wrapped around his right arm he found it difficult to get a grip on the filler cap with his frozen fingers. When he did get the cap off he had to feed the flapping hose into the tank at exactly the right angle. As he pushed the door open to climb back in his foot slipped off the wing and he was left hanging on with only his left hand. When he finally fell back in his seat he was exhausted.

Petersen dug out the only food they had brought with them, a packet of biscuits and a small bottle of grape juice. They helped Thomas to recover sufficiently to take over the controls. Then he held the refuelling tube with one hand while Petersen, kneeling on his seat, put in the funnel and opened the first can of petrol. The slipstream swirling in through the broken windows blew petrol everywhere. More was spilled with every bump of the Hornet Moth. Soon both men were soaked in petrol and getting colder and colder as it evaporated. They were affected worst by the fumes which quickly became unbearable. They had to stop pouring petrol to be able to breathe. As much petrol was wasted as went into the tank. The process went on for forty five minutes, pouring, retching, recovering.

The sun had risen behind them when they saw the Northumberland coast ahead. They had confirmation that it was England when Petersen pointed out a formation of four Hurricanes overhead. They had been detected by radar and plotted by the Observer Corps. Thomas checked to see if his white flag was still there. It was though all but the last six inches had blown away. A Spitfire flew past them alongside, the pilot pointing downwards. Thomas rejected the first field that looked suitable. There were sheep in it - and telephone wires. The next field was fine and the Hornet Moth rumbled to a stop alongside a gate leading to a road alongside. It was 5.30 am on 22nd June 1941.

The two weary pilots pulled off their petrol soaked overalls. They opened the case in which they had brought fresh white shirts and ties and their uniforms. The first person they met was a farm worker. He refused to tell them where they were. Didn’t they know there was a war on?

Soon two trucks arrived, each with an officer and a driver, both armed. The Danes were taken to nearby RAF Acklington where no-one seemed to believe their story. Nevertheless, they were given breakfast, then taken to the sick bay where they were invited to sleep till lunchtime. More interrogations followed, copious notes were taken and Thomas handed over his precious parcel of films.

This story has been about the remarkable flight of Thomas Sneum and Kjeld Petersen across the North Sea but it can’t be left without covering some of the aftermath.

What happened to the films is covered by R V Jones in his book ‘Most Secret War’. The undeveloped films reached MI5 and were given to the Post Office for processing. It all went badly wrong and the films were ruined. Just one or two frames showed anything useful. Sneum was furious but agreed to be parachuted back into Denmark to work for MI5. There were other agents in Denmark but they worked with SOE, the Special Operations Executive which was charged by Churchill to ‘set Europe ablaze’. Incredibly MI5 and SOE worked entirely independently of each other, resented each other’s presence and even worked against each other. Sneum’s mission in Denmark was a failure and he escaped to Sweden by walking across the frozen sea. When he got to England he spent some time in Brixton Prison (at the instigation of SOE) but was released and joined the RAF. He flew in a Mosquito squadron and R V Jones persuaded the RAF to let him lead his squadron into Copenhagen Airport on the liberation of Denmark at the end of the war.

Kjeld Petersen flew Spitfires in the RAF and after the war rose to the rank of Lt. Colonel in the Danish Air Force.

Poul Andersen never got his Hornet Moth back but he did get away with any involvement with its flight to England.

The Broomstick and what was left of the towel hung on a wall in RAF Acklington for many years.