The Flying Flea (May 2019)

It is modestly displayed. It hangs quietly out of the way in one of Shuttleworth’s hangars - a small silver and blue light aeroplane, usually overlooked (underlooked?) by visitors. Yet once, this little craft took the flying world by storm and attracted the attention of an army of would-be aviators. It seemed to be the key which would open the door, closed to many, of aeroplane ownership and pilotage. The man who designed it chose to tell the world the story of his own stumbling progress of learning to build his own flying machine and teaching himself to fly it.

Henri Mignet was born in 1893 and as a teenager became interested in flight. Although, by 1911, Wilbur Wright’s demonstrations of his Flyer in France had triggered an outburst of building and flying of many practical experimental aeroplanes Henri went back to the beginning. He wrote to Gustav Lilienthal about his brother Otto’s gliding in the 1890s and also dipped into Octave Chanute’s writings about his gliders which were tested in the States about the same time.

He was training to be an electrician when he produced a design for a Lilienthal-style glider, which he proudly called HM-1, then a Chanute-style biplane glider, closely followed by a Bleriot-style monoplane. The outbreak of war brought everything to a halt. Henri joined up and spent the war as a wireless operator. In 1918, he contracted malaria, seriously enough to be discharged as unfit for service.

He was training to be an electrician when he produced a design for a Lilienthal-style glider, which he proudly called HM-1, then a Chanute-style biplane glider, closely followed by a Bleriot-style monoplane. The outbreak of war brought everything to a halt. Henri joined up and spent the war as a wireless operator. In 1918, he contracted malaria, seriously enough to be discharged as unfit for service.

Picking up the threads of getting airborne, Henri designed a motor-glider, the HM-2 (a bit like a Bleriot- ‘all the parts worked, but not together’). Next came HM-3, the Dromedary, then he built the HM-4, a Parasol, powered by a 10 hp Anzani engine. The 21 ft wing was set well forward and its entire rear half was hinged. The controls could move both ‘flaps’ together, like elevons or differentially, like ailerons. Henri’s extensive study of birds in flight showed that they flew perfectly well without a rudder, so his parasol had none. Instead, the tailplane was attached by a longitudinal hinge so that it could rock from side to side.

Trials began in June 1923. Henri couldn’t keep the Parasol rolling in a straight line and an inconveniently placed tree brought the trials to a swift end.

Trials began in June 1923. Henri couldn’t keep the Parasol rolling in a straight line and an inconveniently placed tree brought the trials to a swift end.

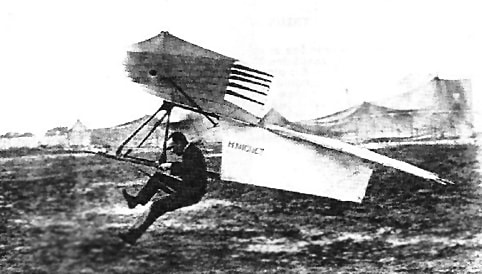

Next, he built HM-5, a foot launched glider. The photographs show less than serious attempts at launching but they seem to be just what the press photographer wanted. However, it is on record that Henri won a prize with this glider at Vauville, a gliding site in Southern France.

In 1923 he set up a business making and selling radio sets. Clearly, it didn’t make enough money so he turned to chicken farming to finance his next project, the HM-6, a pusher aeroplane with a power unit that was soon adapted to fit into the HM-7, an ultra-light helicopter. In 1926 he took time out from aviation to marry Annette Triou, move to Paris and get a job with Philips. Their son François was born in 1927 and Henri showed his versatility by using the workings of an old clock to make a 9.5 mm movie camera.

He took the components from the HM-6 and 7 and built them into the HM-8, an aeroplane fitted with ‘conventional’ controls in that he added ailerons. Control in pitch was achieved, not by elevators, but by varying the angle of the wing. The most significant thing about the HM-8, which he called the Avionnette, was that it actually worked.

In 1923 he set up a business making and selling radio sets. Clearly, it didn’t make enough money so he turned to chicken farming to finance his next project, the HM-6, a pusher aeroplane with a power unit that was soon adapted to fit into the HM-7, an ultra-light helicopter. In 1926 he took time out from aviation to marry Annette Triou, move to Paris and get a job with Philips. Their son François was born in 1927 and Henri showed his versatility by using the workings of an old clock to make a 9.5 mm movie camera.

He took the components from the HM-6 and 7 and built them into the HM-8, an aeroplane fitted with ‘conventional’ controls in that he added ailerons. Control in pitch was achieved, not by elevators, but by varying the angle of the wing. The most significant thing about the HM-8, which he called the Avionnette, was that it actually worked.

Henri wrote a book ‘How I built my Avionnette’ which included plans. It was taken up enthusiastically by amateurs and over 200 were built with power units varying from 17 to 50 hp. Henri himself built and sold six.

Suddenly, Henri lost all interest in his Avionnette when he crashed in it after stalling in a low turn. Physically he was unhurt but he lost all faith in his creation now viewing it as unsafe and therefore a failure. His aim had been to build a truly safe aeroplane which could not stall. He burnt his crashed machine, built a wind tunnel and began experimenting again.

Suddenly, Henri lost all interest in his Avionnette when he crashed in it after stalling in a low turn. Physically he was unhurt but he lost all faith in his creation now viewing it as unsafe and therefore a failure. His aim had been to build a truly safe aeroplane which could not stall. He burnt his crashed machine, built a wind tunnel and began experimenting again.

As a diversion he spent some time with a friend who had a Potez 43. They toured northern France and Henri spent some time at the controls. He found that he couldn’t cope with it at all. It was ‘a machine quite beyond me’, he said. He was even more determined to build an aeroplane that would be easy for the man in the street to build and to fly and which was essentially SAFE.

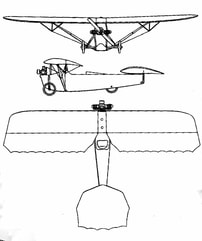

The HM-9 was to have wings which could swivel. The HM-10 had the engine behind the pilot with a shaft driving the propeller in the nose. The HM-11 was a triplane, of sorts. He understood the value of the slot which delays the onset of the stall and the HM-11’s forward wings were one giant slot. The HM-12 was a modification which brought the wings together as a single slotted wing. He believed that controlling the lifting wing by moving the tailplane introduced a delay in the controls. Adjusting the wing angle directly would give an immediate reaction and the pilot would ’have a more sensitive feel’. So both the HM-11 and 12 had fixed tailplanes and control was achieved by varying the angle of the forward wing.

He reasoned that the pivot point of the wing should be ahead of the Centre of Pressure so that the wing was always trying to reduce its angle of attack and so avoid stalling. To ‘stabilize the movement of the Centre of Pressure’ and add more ‘feel’ to the controls, he swept up the trailing edge of the wing so that it had a reflex aerofoil. It became, in his words, ‘a living wing’.

Finally, for the HM-14, he decided to get rid of the ‘dreaded’ ailerons. Turning would be done ‘naturally’ by the rudder alone, operated by moving the stick sideways. This would yaw the aeroplane, speed up the outer wing and produce more lift and thus roll. He built in dihedral and in testing, swept up the wing tips. This changed the angle of the tips to the airflow and added even more lift to the outer wing to help the turn.

He reasoned that the pivot point of the wing should be ahead of the Centre of Pressure so that the wing was always trying to reduce its angle of attack and so avoid stalling. To ‘stabilize the movement of the Centre of Pressure’ and add more ‘feel’ to the controls, he swept up the trailing edge of the wing so that it had a reflex aerofoil. It became, in his words, ‘a living wing’.

Finally, for the HM-14, he decided to get rid of the ‘dreaded’ ailerons. Turning would be done ‘naturally’ by the rudder alone, operated by moving the stick sideways. This would yaw the aeroplane, speed up the outer wing and produce more lift and thus roll. He built in dihedral and in testing, swept up the wing tips. This changed the angle of the tips to the airflow and added even more lift to the outer wing to help the turn.

Henri finished building the first of what would become the HM-14 in September 1933. He wanted to keep the testing of it away from any airfield and its curious pilots and engineers so he towed it behind his car into the country and found a large open field where he set up camp.

Testing was prolonged. Almost every attempt to fly resulted in some damage. It didn’t help that his 500cc two-stroke motor cycle engine was unreliable and liable to seize after a few minutes running. Repairs became modifications. The forward wing was lowered by four inches. The rear wing span was shortened by three feet. The Centre of Gravity, which didn’t seem to be critical in an aircraft with a lifting wing at nose and tail, wandered about with every modification and happily settled in what seemed to be a comfortable place. Hops became longer and arrivals (with breakages) became landings. Henri persevered until he finally flew a full circuit. It was the 8th of November. It had taken nearly two months for the HM-14 design to become a practical aeroplane, literally, by accident(s). Thrilled with success and filled with confidence he flew higher and longer.

On 1st December he took off for a duration test. He hadn’t been flying long when the fuel cock under the tank became unsoldered and he was showered with petrol. He switched off the engine and force landed in a ploughed field, bouncing over the furrows. He could now reach the tank and put his thumb over the hole. A group of farm labourers came up and they, conveniently, had a wine bottle cork. Henri put the fuel cock in his pocket, jammed the pipe into the hole with the cork and took off, flying back to his camp for a change of clothes. There was still enough daylight to fly a few more circuits, all with the cork in place.

One day some friends came to see him fly – one was a pilot. The wind was strong and gusty but Henri thought his little aeroplane was doing so well that he would have no trouble and his friends would be impressed. (Clearly he didn’t remember, or even know, that both Otto Lilienthal and Percy Pilcher had both died doing exactly what he was about to do). As soon as he left the ground he was buffeted by gusts and climbed to find smoother air. At 300 feet he found the wind was blowing at 60 mph. He fought his way back to his field and landed where he could. The only thing broken was a branch or two in the wood he ran into. That didn’t matter. His frightening excursion was the final proof of how successful his latest design was and he towed it home in triumph.

Testing was prolonged. Almost every attempt to fly resulted in some damage. It didn’t help that his 500cc two-stroke motor cycle engine was unreliable and liable to seize after a few minutes running. Repairs became modifications. The forward wing was lowered by four inches. The rear wing span was shortened by three feet. The Centre of Gravity, which didn’t seem to be critical in an aircraft with a lifting wing at nose and tail, wandered about with every modification and happily settled in what seemed to be a comfortable place. Hops became longer and arrivals (with breakages) became landings. Henri persevered until he finally flew a full circuit. It was the 8th of November. It had taken nearly two months for the HM-14 design to become a practical aeroplane, literally, by accident(s). Thrilled with success and filled with confidence he flew higher and longer.

On 1st December he took off for a duration test. He hadn’t been flying long when the fuel cock under the tank became unsoldered and he was showered with petrol. He switched off the engine and force landed in a ploughed field, bouncing over the furrows. He could now reach the tank and put his thumb over the hole. A group of farm labourers came up and they, conveniently, had a wine bottle cork. Henri put the fuel cock in his pocket, jammed the pipe into the hole with the cork and took off, flying back to his camp for a change of clothes. There was still enough daylight to fly a few more circuits, all with the cork in place.

One day some friends came to see him fly – one was a pilot. The wind was strong and gusty but Henri thought his little aeroplane was doing so well that he would have no trouble and his friends would be impressed. (Clearly he didn’t remember, or even know, that both Otto Lilienthal and Percy Pilcher had both died doing exactly what he was about to do). As soon as he left the ground he was buffeted by gusts and climbed to find smoother air. At 300 feet he found the wind was blowing at 60 mph. He fought his way back to his field and landed where he could. The only thing broken was a branch or two in the wood he ran into. That didn’t matter. His frightening excursion was the final proof of how successful his latest design was and he towed it home in triumph.

Henri had introduced another oddity which made the HM-14 different. Unlike other tandem wing machines, it was controlled by pivoting the fore wing, so if he pulled back the stick to climb (increasing the wing’s angle of attack) the fuselage stayed level.

Fizzing with the success of his aeroplane, Henri burst into print. ‘If you are able to nail together a packing case, you are able to build a Flying Flea’. (Henri was quite sure that he had built the Model T of the air and since the Model T was known as the ‘Pou de la Route’ then his HM-14 had to be the ‘Pou du Ciel’). His book was called ‘Le Sport de l'Air’ and contained plans (sketches with dimensions marked) and building instructions for the Pou.

The book sold like hot croissants, was translated into English and serialised in Popular Mechanics in the USA. Sheds across the Western world echoed with the sound of hammering and sawing.

‘Le Sport de l'Air’ was translated and published in England by the Air League of the British Empire. 6000 copies sold out in a month. A second edition was hurriedly produced. The preface, by its Secretary, Air Commodore J A Chamier, offered help to builders (‘please send a stamp’) and contained lists of suppliers of materials.

Fizzing with the success of his aeroplane, Henri burst into print. ‘If you are able to nail together a packing case, you are able to build a Flying Flea’. (Henri was quite sure that he had built the Model T of the air and since the Model T was known as the ‘Pou de la Route’ then his HM-14 had to be the ‘Pou du Ciel’). His book was called ‘Le Sport de l'Air’ and contained plans (sketches with dimensions marked) and building instructions for the Pou.

The book sold like hot croissants, was translated into English and serialised in Popular Mechanics in the USA. Sheds across the Western world echoed with the sound of hammering and sawing.

‘Le Sport de l'Air’ was translated and published in England by the Air League of the British Empire. 6000 copies sold out in a month. A second edition was hurriedly produced. The preface, by its Secretary, Air Commodore J A Chamier, offered help to builders (‘please send a stamp’) and contained lists of suppliers of materials.

The timing of book and the Flea’s arrival in England was fortuitous. There was already a campaign to relax the Air Ministry’s rigorous standards of aircraft construction for the small number of light aircraft and motor gliders which a few individuals had made. The Air League’s promotion of the Flea forced the Ministry’s hand. They decreed that any ‘A’ licence holding pilot needed only third party insurance of £5000 to fly light aircraft anywhere and, significantly, any unlicensed would-be pilot could fly what he liked, as high as he liked provided he stayed within three miles of his airfield.

The Air League promptly built a Flea and displayed it in Selfridge’s new store. The first Flea to fly was built by 22 year old Stephen Appleby. He was a little ahead of the game. He had lived in France, had built and learned to fly an HM-8 and knew Mignet well. Henri had sent him an advance copy of his book and he began building his Flea at Heston, where he was employed by Airwork. He used an old Ford 10 hp engine which got the Flea off the ground, over the hedge and into the next ploughed field where it crashed. With its low ground clearance – only half a wheel height – the belly had dragged on the rough ground, dug in and neatly inverted the Flea.

The Air League promptly built a Flea and displayed it in Selfridge’s new store. The first Flea to fly was built by 22 year old Stephen Appleby. He was a little ahead of the game. He had lived in France, had built and learned to fly an HM-8 and knew Mignet well. Henri had sent him an advance copy of his book and he began building his Flea at Heston, where he was employed by Airwork. He used an old Ford 10 hp engine which got the Flea off the ground, over the hedge and into the next ploughed field where it crashed. With its low ground clearance – only half a wheel height – the belly had dragged on the rough ground, dug in and neatly inverted the Flea.

Help was soon at hand. The Flea flop had been witnessed by Stephen Appleby’s boss, Sir John Carden, an engineer who advised Vickers Armstrong on tank design. He offered a much lighter conversion of a Ford engine which would produce 30 hp for the Flea. Sir John’s partner, Leslie Baynes, was a capable aeronautical engineer and offered to help Appleby with the rebuild. More help came from the Daily Express who handed over £100 to help defray the cost of the repair of the Flea.

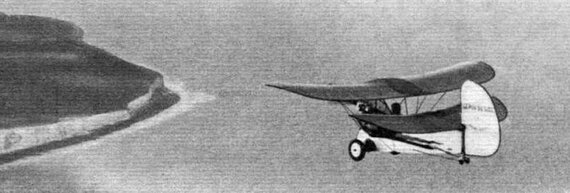

A greatly improved Flea emerged. Baynes increased the span and chord of the front wing, changed the cable controls to rods and generally tidied up and strengthened where he could. Stephen Appleby, in the photograph, is clearly very happy with the result.

A greatly improved Flea emerged. Baynes increased the span and chord of the front wing, changed the cable controls to rods and generally tidied up and strengthened where he could. Stephen Appleby, in the photograph, is clearly very happy with the result.

Sir John suggested that Appleby should, like Mignet, fly the Channel. On 5 December Appleby took off from Lympne and a few minutes later landed at an airfield near Calais where pre-publicity had generated a small crowd who were waiting to greet him.

Delight in this achievement was dissipated just five days later when the airliner bring Sir John Carden home from Belgium crashed in fog and Sir John was killed.

Nevertheless, Appleby went ahead with the Carden-Baynes plan to tow the Flea around the country, displaying it in car showrooms and flying it at weekend displays – admission 6d. It was a huge and profitable success and orders were taken for 60 Baynes Cantilever Fleas. One event got an enthusiastic write up in the Thanet Advertiser.

FLYING FLEAS. AIR RACE THRILLS. FRANCE v ENGLAND

A crowd of four thousand people cheered at Ramsgate Airport on Monday afternoon as a tiny little 'plane zoomed a few hundred feet above their heads. They were congratulating the winner of the first international challenge race for "Flying Flea" types of aircraft. A thrilling race it was between French and English pilots - and it was carried through without mishap.

The race, which was the main attraction of an afternoon of aerial thrills, was round four laps of a seven-and-a-half mile course, the points of which were Ramsgate Airport, Manston R.A.F. Station, Margate refuse destructor and Rumsfield water tower. Each machine was handicapped according to its individual features. Seven "Fleas" - three English, three French and one English machine piloted by a Frenchman - competed and only one gave up.

The winning airman was Monsieur E. Brett, son of the proprietor of the Hotel des Anglais, Cannes, whose Ava engined machine covered the course in 29 mins 4 secs. His average speed over the 30 miles course was 56¾ miles an hour. His victory gained him £100 in cash and a magnificent silver challenge trophy.

The second man home was Mr. S. V. Appleby, pioneer of Flying Flea aircraft in England, whose Carden-Ford machine completed the course in a corrected time of 27 mins 45 secs - an average speed of 59½ miles an hour, the fastest of the day.

Third prize was won by Monsieur R. Robineau, a tailor, of Braine, France who finished in 33 minutes dead - an average speed of 50 miles an hour. The remaining competitors in order of finishing were: 4th - Mr. C.A. Oscroft of Ashingdon, Essex; 5th - Mons. J. Colli of Antibes, France; 6th - Mons. V. Lane of St. Maxence, Oise, France. Flying Officer A.E. Clouston of R.A.F. Farnborough, was forced to give up after the first lap owing to a burst oil pipe but made a perfect landing.

On top of the control tower a few minutes later, the Mayoress of Ramsgate (Mrs. H. Stead) presented the trophies and prizes to the successful competitors. Amongst the trophies was a small silver cup which the Mayoress presented to M. Mignet, the inventor of the "Flying Flea" or "Pou-de-Ciel", who was an interested spectator of the race.

The newspaper listed 22 Fleas registered in the local area, including G-AEFW (which had been damaged in a heavy landing), G-AEBB, built by K Owen (which is now in Shuttleworth’s hangar) and G-AEFV, later used in the Farnborough wind tunnel tests.

Comparison with Mignet’s prototype and the Baynes Flea flown by Stephen Appleby in this race is interesting.

HM-14 Prototype Baynes Flea

Engine 17 hp Aubier- Dunne M/c 30 hp Carden-Ford

Span 19’ 6” 20’ 0”

Length 11’ 6” 13’ 0”

Wing area 119 sq ft 137 sq ft

Weight – take off 420 lbs 545lbs

Max speed 62 mph 82 mph

Climb 200 ft/min 300 ft/min

So much for sticking to the plans.

Delight in this achievement was dissipated just five days later when the airliner bring Sir John Carden home from Belgium crashed in fog and Sir John was killed.

Nevertheless, Appleby went ahead with the Carden-Baynes plan to tow the Flea around the country, displaying it in car showrooms and flying it at weekend displays – admission 6d. It was a huge and profitable success and orders were taken for 60 Baynes Cantilever Fleas. One event got an enthusiastic write up in the Thanet Advertiser.

FLYING FLEAS. AIR RACE THRILLS. FRANCE v ENGLAND

A crowd of four thousand people cheered at Ramsgate Airport on Monday afternoon as a tiny little 'plane zoomed a few hundred feet above their heads. They were congratulating the winner of the first international challenge race for "Flying Flea" types of aircraft. A thrilling race it was between French and English pilots - and it was carried through without mishap.

The race, which was the main attraction of an afternoon of aerial thrills, was round four laps of a seven-and-a-half mile course, the points of which were Ramsgate Airport, Manston R.A.F. Station, Margate refuse destructor and Rumsfield water tower. Each machine was handicapped according to its individual features. Seven "Fleas" - three English, three French and one English machine piloted by a Frenchman - competed and only one gave up.

The winning airman was Monsieur E. Brett, son of the proprietor of the Hotel des Anglais, Cannes, whose Ava engined machine covered the course in 29 mins 4 secs. His average speed over the 30 miles course was 56¾ miles an hour. His victory gained him £100 in cash and a magnificent silver challenge trophy.

The second man home was Mr. S. V. Appleby, pioneer of Flying Flea aircraft in England, whose Carden-Ford machine completed the course in a corrected time of 27 mins 45 secs - an average speed of 59½ miles an hour, the fastest of the day.

Third prize was won by Monsieur R. Robineau, a tailor, of Braine, France who finished in 33 minutes dead - an average speed of 50 miles an hour. The remaining competitors in order of finishing were: 4th - Mr. C.A. Oscroft of Ashingdon, Essex; 5th - Mons. J. Colli of Antibes, France; 6th - Mons. V. Lane of St. Maxence, Oise, France. Flying Officer A.E. Clouston of R.A.F. Farnborough, was forced to give up after the first lap owing to a burst oil pipe but made a perfect landing.

On top of the control tower a few minutes later, the Mayoress of Ramsgate (Mrs. H. Stead) presented the trophies and prizes to the successful competitors. Amongst the trophies was a small silver cup which the Mayoress presented to M. Mignet, the inventor of the "Flying Flea" or "Pou-de-Ciel", who was an interested spectator of the race.

The newspaper listed 22 Fleas registered in the local area, including G-AEFW (which had been damaged in a heavy landing), G-AEBB, built by K Owen (which is now in Shuttleworth’s hangar) and G-AEFV, later used in the Farnborough wind tunnel tests.

Comparison with Mignet’s prototype and the Baynes Flea flown by Stephen Appleby in this race is interesting.

HM-14 Prototype Baynes Flea

Engine 17 hp Aubier- Dunne M/c 30 hp Carden-Ford

Span 19’ 6” 20’ 0”

Length 11’ 6” 13’ 0”

Wing area 119 sq ft 137 sq ft

Weight – take off 420 lbs 545lbs

Max speed 62 mph 82 mph

Climb 200 ft/min 300 ft/min

So much for sticking to the plans.

Those who did stick to the plans were having problems, principally in finding a suitable engine. Not many Carden Fords were yet available and the twin cylinder Flying Squirrel from the Scott motorcycle company was still only a promise. Even with a suitable engine, take off was quite tricky. The very short undercarriage didn’t like rough ground and steering was by twin tailwheels attached to the base of the rudder giving an abrupt response to lateral stick movement. But the real problem was inherent in the design.

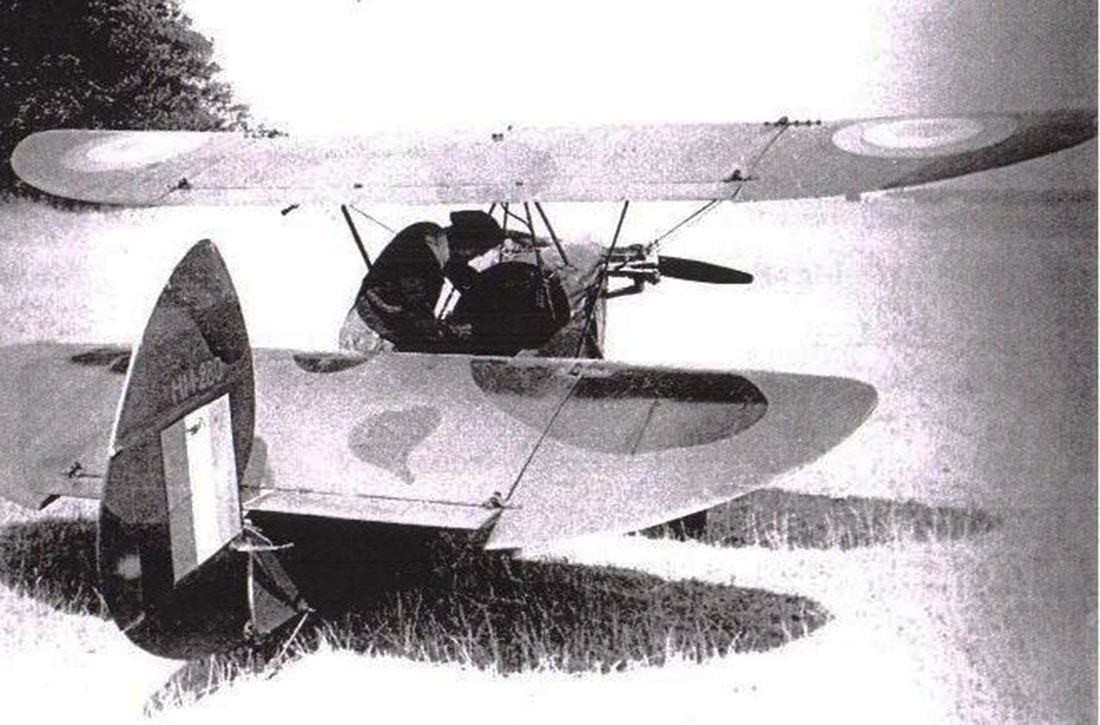

Note the very narrow slot in comparison with Appleby’s Flea.

Note the very narrow slot in comparison with Appleby’s Flea.

The arrangement of the wings meant that they acted, deliberately, like a huge slot, encouraging the air to flow smoothly over the rear wing. What was not intended happened if the wings were too close together. Then, the narrowing of the slot would cause the airflow over the rear wing to increase significantly and produce more lift, thus lifting the tail. This is exactly what occurred when the pilot wanted to recover from a dive. He would pull back the stick, increasing the angle of the front wing and narrowing the slot. The extra lift from the rear wing, with its greater moment arm from the C.G., would force the nose down so increasing the dive. As the speed increased, so did the downward pitching force. Most Fleas completed the manoeuvre by turning neatly upside down. If they weren’t very high, which few Fleas ever were, they dived into the ground.

This wasn’t fully understood at the time and certainly not all Fleas seemed to be affected. Several manufacturers started Flea production) and Arthur Clouston (a Farnborough test pilot and one of the entrants in the Ramsgate race) earned £5 a time for completing a quick circuit in Fleas which were to be sold as having genuinely flown. Interestingly, this is after he had previously suffered from a different Flea which had turned inverted. He had somehow recovered only because he had taken the Flea up to 600 feet.

Fleas were tested in wind tunnels in France and in England. It was found that, as well as the size of the slot the position of the centre of gravity was critical. Mignet’s building instructions suggested moving the rear wing to and fro to get the CG in the right position and, since both the amateurs’ build quality and the weight of various components were variable, this could bring the wings too close together.

It was in August 1935, when Mignet was on his triumphal tour in England, that the first fatality occurred in Algeria, though the news took some time to spread. The next month, in France, a flying instructor died and there were two more deaths in March 1936. When a Swiss pilot died, also in March, the Swiss immediately banned the Flea.

On this side of the Channel, A. H Anderson died In Scotland in April 1936. He was a novice pilot, which might have had a bearing on the accident, but the following month a test pilot, Flt. Lt. Ambrose Cowell, died at Penshurst. Days later Sqn Ldr Charles Davidson, chief flying instructor at RAF Digby was also killed.

France had stopped Flea flying pending the results of tests. In the UK, the Air Ministry didn’t issue a ban. They simply announced that no more Authorisations to Fly would be issued. That was effective enough for Flea construction generally to grind to a halt although James Goodall had enough confidence in his finished Flea to fly it in September. His was the fourth British death and he was killed, not by faulty aerodynamics – he crashed normally into an inconvenient ditch.

121 Fleas had been registered in the UK and it was estimated that a further 350 were under construction. Leslie Baynes was geared up to produce 60 of his modified - and safe - Fleas but decided against it. In September Henri Mignet revisited Britain with his improved Model HM-18. He demonstrated it at Heston but it side-slipped into the ground when landing. When he took it home to repair it all things Flea left British skies for good.

Henri quickly prepared revised drawings for the HM-18 showing a lengthened fuselage to eliminate any overlap of the wings. A variation included a pivot for the rear wing to decrease its incidence when the front wing’s was increased. A suggested quick fix for the HM-14 was to fit the rear wing further back on the fuselage cutting a vee in the trailing edge to clear the rudder. Although Henri protested to officialdom and all that his beloved Flea was now safe he met a wave of scepticism. The Flea craze was definitely at an end.

Henri didn’t give up. He set up the Mignet Aircraft Company to produce his aeroplanes and designs flowed from his drawing board. The HM-17, a two seater with an enclosed cabin, the HM-18, of course, now with an enclosed cabin, HM-19, side-by-side two seater and the HM-210, an improved version of the HM-18 which actually obtained a Certificate of Airworthiness in England. He visited the USA and set up the American-Mignet Company to produce the HM-20, the HM-21 and the two seat HM-23.

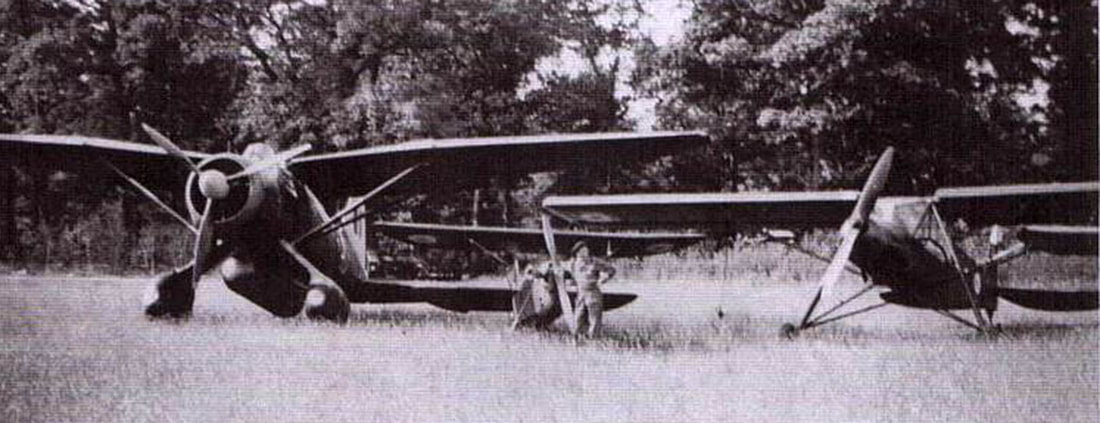

The outbreak of war in September 1939 brought a halt to all this activity – but not entirely for Henri. He went on working on a new design – the HM-250, an enclosed cockpit 3- seater. Although Henri’s wife, Annette, was tragically killed in a shoot-out between rival Maquis groups Henri responded to a request in 1944, from a Colonel Eon, to design and build a Flea to be used by the underground movement. Only one HM-280 was built and how it was used is unclear but in the photograph it proudly stands alongside a Lysander and a Storch in a post-war display of the ‘Maquis Air Force’.

This wasn’t fully understood at the time and certainly not all Fleas seemed to be affected. Several manufacturers started Flea production) and Arthur Clouston (a Farnborough test pilot and one of the entrants in the Ramsgate race) earned £5 a time for completing a quick circuit in Fleas which were to be sold as having genuinely flown. Interestingly, this is after he had previously suffered from a different Flea which had turned inverted. He had somehow recovered only because he had taken the Flea up to 600 feet.

Fleas were tested in wind tunnels in France and in England. It was found that, as well as the size of the slot the position of the centre of gravity was critical. Mignet’s building instructions suggested moving the rear wing to and fro to get the CG in the right position and, since both the amateurs’ build quality and the weight of various components were variable, this could bring the wings too close together.

It was in August 1935, when Mignet was on his triumphal tour in England, that the first fatality occurred in Algeria, though the news took some time to spread. The next month, in France, a flying instructor died and there were two more deaths in March 1936. When a Swiss pilot died, also in March, the Swiss immediately banned the Flea.

On this side of the Channel, A. H Anderson died In Scotland in April 1936. He was a novice pilot, which might have had a bearing on the accident, but the following month a test pilot, Flt. Lt. Ambrose Cowell, died at Penshurst. Days later Sqn Ldr Charles Davidson, chief flying instructor at RAF Digby was also killed.

France had stopped Flea flying pending the results of tests. In the UK, the Air Ministry didn’t issue a ban. They simply announced that no more Authorisations to Fly would be issued. That was effective enough for Flea construction generally to grind to a halt although James Goodall had enough confidence in his finished Flea to fly it in September. His was the fourth British death and he was killed, not by faulty aerodynamics – he crashed normally into an inconvenient ditch.

121 Fleas had been registered in the UK and it was estimated that a further 350 were under construction. Leslie Baynes was geared up to produce 60 of his modified - and safe - Fleas but decided against it. In September Henri Mignet revisited Britain with his improved Model HM-18. He demonstrated it at Heston but it side-slipped into the ground when landing. When he took it home to repair it all things Flea left British skies for good.

Henri quickly prepared revised drawings for the HM-18 showing a lengthened fuselage to eliminate any overlap of the wings. A variation included a pivot for the rear wing to decrease its incidence when the front wing’s was increased. A suggested quick fix for the HM-14 was to fit the rear wing further back on the fuselage cutting a vee in the trailing edge to clear the rudder. Although Henri protested to officialdom and all that his beloved Flea was now safe he met a wave of scepticism. The Flea craze was definitely at an end.

Henri didn’t give up. He set up the Mignet Aircraft Company to produce his aeroplanes and designs flowed from his drawing board. The HM-17, a two seater with an enclosed cabin, the HM-18, of course, now with an enclosed cabin, HM-19, side-by-side two seater and the HM-210, an improved version of the HM-18 which actually obtained a Certificate of Airworthiness in England. He visited the USA and set up the American-Mignet Company to produce the HM-20, the HM-21 and the two seat HM-23.

The outbreak of war in September 1939 brought a halt to all this activity – but not entirely for Henri. He went on working on a new design – the HM-250, an enclosed cockpit 3- seater. Although Henri’s wife, Annette, was tragically killed in a shoot-out between rival Maquis groups Henri responded to a request in 1944, from a Colonel Eon, to design and build a Flea to be used by the underground movement. Only one HM-280 was built and how it was used is unclear but in the photograph it proudly stands alongside a Lysander and a Storch in a post-war display of the ‘Maquis Air Force’.

The Maquis-Flea had developed – enclosed cockpit, trim tabs on rear wing and rudder and folding

wings, enabling it to be towed, backwards, by a motor cycle.

wings, enabling it to be towed, backwards, by a motor cycle.

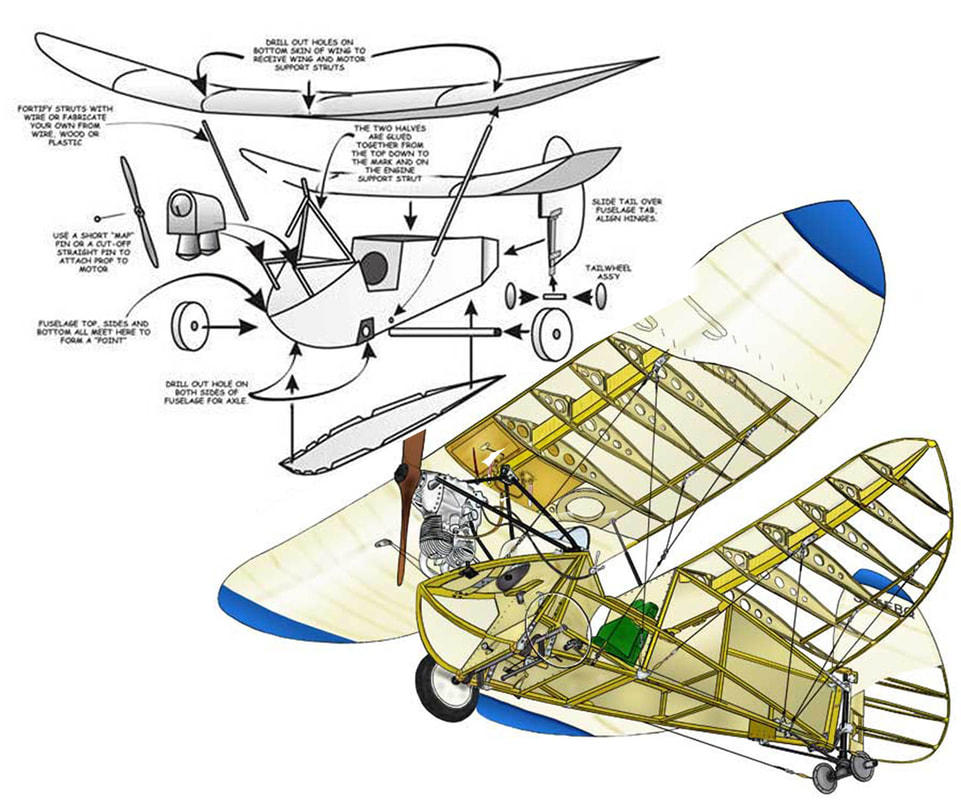

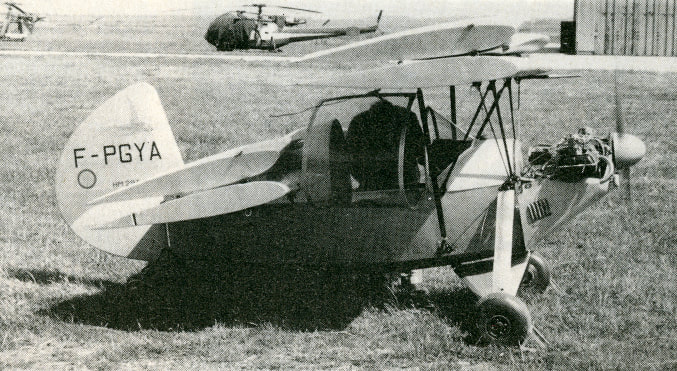

Post-war, Henri enlarged the HM-280 to become the HM-290 but this enthusiast (above left) resisted the improvements to build his own ‘warbird’. Plans for the HM-290 (above right) are still available and that, and the slightly larger HM-293 which came off the drawing board in 1946 could still be being built today.

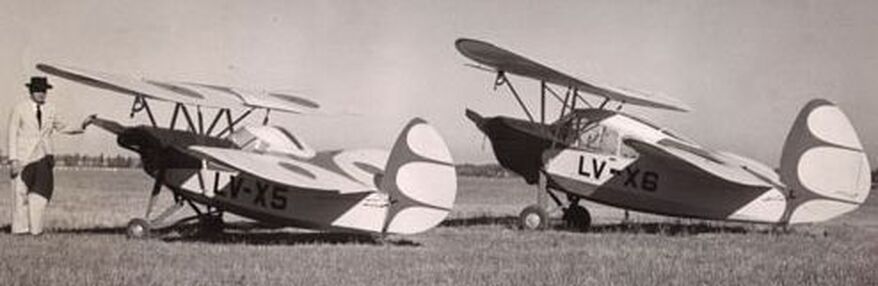

Henri left France in 1947 for Argentina where he set up a factory to produce the single seat HM-294, La Pulga Pulga and the three seat HM-300, Annette.

Henri left France in 1947 for Argentina where he set up a factory to produce the single seat HM-294, La Pulga Pulga and the three seat HM-300, Annette.

He had continual problems with the disinterested Argentinian authorities when trying to get his prototypes tested and certificated although his presence in the country generated a little outburst of home building in the 1930s Flea Fan community. In frustration, Henri moved over the border to Brazil in 1952 to produce the two seat HM-310, Estafette.

Two years later, he was off to Japan where the HM-330 was produced as the Tachikawa R-HM Cherry Blossom, derived from the 310.

Then in 1955 he moved to Morocco. A factory in Casablanca made the HM-320 (single seat) and the HM-350 two seater.

None of these overseas ventures could be considered a success and Henri came home to France. Subsequent ideas were no more than ‘studies’ and in 1965 Henri succumbed to cancer.

Then in 1955 he moved to Morocco. A factory in Casablanca made the HM-320 (single seat) and the HM-350 two seater.

None of these overseas ventures could be considered a success and Henri came home to France. Subsequent ideas were no more than ‘studies’ and in 1965 Henri succumbed to cancer.

The baton of the Flea was picked up by Henri’s son and nephew. They reworked the design to produce the HM-1000 Balerit made of aluminium tube and powered by a 64 hp Rotax engine. It first flew in 1986 and 135 were made. It was even used by the French Army, who bought 24. The Flea’s tandem wing arrangement was still used but the increased separation of the wings made it safer. It had an interesting ‘safety feature’. If the pilot raised the nose to make it stall, it wouldn’t behave like a normal aeroplane. It would settle into a ‘comfortable stable parachute-like descent’. As you can see, HM-1000s have been flying, duly certificated and registered, in Britain.

The next model with a smarter and more modern look was the HM1100 Cordouan which appeared in 1998. Not intended to be sold as a kit, it met the French ULM or ultralight category, having a maximum take-off weight under 450 kgs. The fuselage was of steel tube construction with a fibre glass shell incorporating a cockpit seating two side by side. The fore wing was ‘free’, fixed only to a pivot allowing it vary its angle to absorb turbulence. The pilot’s stick operated a Flettner tab – a hinged trailing edge – which controlled pitch. Another innovation was the fitting of ailerons on the rear wing, giving the Cordouan a classic three-axis control via (dual) rudder pedals and a single central control stick. (This solved a problem which afflicted all Fleas when trying to land in a crosswind. Rudder is needed to line up the wheels on touchdown but the Flea’s rudder also induced roll which is definitely not needed).

Fitted with a Rotax 912, the prototype maximum speed was 117 mph and normal cruise 93 mph. It could take off fully loaded from an 80 metre (260 ft) grass strip, and land even shorter. Its 80 hp Rotax engine gave it a cruising speed of 93 mph.

The Mignets went out of business in 2005 but the Flea lives on. Anyone with aspirations to build one can no longer buy a kit but plans are available from two sources, both amateur builders who updated and redrew the original plans. Rodolphe Grunberg of France is responsible for the most commonly built of all Mignet designs today, the HM-293RG. His plans are in French but very clearly and simply drawn and an English-language key is also available from Paul Pontois in Canada. Fred Byron of Australia has also come out with updated and redrawn plans and his version, too, has a good reputation.

The Mignets went out of business in 2005 but the Flea lives on. Anyone with aspirations to build one can no longer buy a kit but plans are available from two sources, both amateur builders who updated and redrew the original plans. Rodolphe Grunberg of France is responsible for the most commonly built of all Mignet designs today, the HM-293RG. His plans are in French but very clearly and simply drawn and an English-language key is also available from Paul Pontois in Canada. Fred Byron of Australia has also come out with updated and redrawn plans and his version, too, has a good reputation.

HM-293 variants, with tailwheel, nosewheel, and floats.

The Croses EC-6 Criquet

This Flea review can’t come to an end without mention of the work of Emilien Croses who first met Mignet in Argentina in 1947. He caught the Flea bug and built his own versions, including the Criquet. When he came to design an aeroplane for dropping teams of skydivers or light cargo, he kept the tandem wing layout for the Paras-Cargo. This was quite the largest Flea ever and first flew in 1965. With its 180 hp Lycoming and two crew it could carry 450 kgs (990lbs) of freight. There’s another door at the rear on the starboard side for para-dropping or to make it easier to load two stretchers. The control wheel worked Flea-fashion controlling pitch and yaw (with accompanying roll) but there were also hinged surfaces, large trim tabs, on the rear wing controlled by the two white knobs above the instrument panel – together for pitch, differentially for roll.

Just two were built and they were used briefly in South Africa and France before disappearing quietly into storage.

Just two were built and they were used briefly in South Africa and France before disappearing quietly into storage.