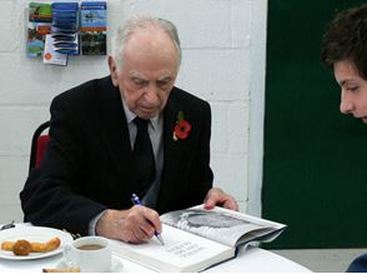

Captain Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown

Talk to SVAS, Shuttleworth - 6 November 2010

Eric Brown was in Germany in 1938. He had been introduced to Ernst Udet and also to Hanna Reitsch and he was in the Deutschlandhalle when she flew the Focke-Achgelis 61 helicopter inside the hall. The practice flights the night before (see picture) had gone well. The next day the audience was deafened by the roaring engine and rotating blades but the helicopter struggled and failed to lift off.

Someone realized that the problem was the changed quality of the air, warmed and de-oxygenated by the breathing of the 8000 strong crowd. The doors were opened to let in fresh air and the helicopter flew and pirouetted around the hall. The enthusiasm of the crowd was muted as the ladies tried to retrieve hats and hair-dos and many of the gentlemen hunted their wigs.

Someone realized that the problem was the changed quality of the air, warmed and de-oxygenated by the breathing of the 8000 strong crowd. The doors were opened to let in fresh air and the helicopter flew and pirouetted around the hall. The enthusiasm of the crowd was muted as the ladies tried to retrieve hats and hair-dos and many of the gentlemen hunted their wigs.

Eric Brown’s next visit to Germany was as head of a group of scientists intent on investigating the state of German research, particularly in jet and rocket propulsion. He was briefly sidetracked by acting as interpreter when Belsen concentration camp was handed over to British troops. This was arranged in an attempt to stop the spread of typhus. Eric’s experience there, including the interrogation of the notorious commandant Jacob Kramer and Irma Grese, left him with unforgettable memories and completely changed his view of the Germans.

More productive interviews were carried out with Herman Goering, Himmler, Adolf Galland, Willy Messerschmitt and other designers. Eric felt the greatest regard for the competence of Kurt Tank who combined the roles of Chief Designer and Assistant Chief Test Pilot for Focke-Wulf.

More productive interviews were carried out with Herman Goering, Himmler, Adolf Galland, Willy Messerschmitt and other designers. Eric felt the greatest regard for the competence of Kurt Tank who combined the roles of Chief Designer and Assistant Chief Test Pilot for Focke-Wulf.

German jet engines used axial-flow compressors and were quite advanced but were hampered by lack of materials. The Jumo 004, which powered the Me 262 and other jets had an expected life of only 25 hours. In practice, their average life was just 12½ hours. He experienced their fragility when preparing to fly an Arado 234 reconnaissance jet. As he opened up the engines to full power for take-off, one of them disintegrated. In all, Eric flew a total of 52 (yes, fifty two) types of German aeroplanes, all without pilot notes or assistance from German pilots, most of whom had disappeared from their airfields. And, although it was against orders, he also flew the dangerous Me 163B rocket-powered fighter, preparing himself by first flying the practice glider and then the unpowered Me-163A.

The Dornier 335, a twin engine single seat fighter with a top speed of 474 mph, had a complicated pilot ejection system which worked in stages. First, the rear propeller was blown off, next the upper fin departed and then the seat was armed. To jettison the canopy the pilot pulled two levers which he had to release smartly because they left with the canopy and could have taken his arms as well.

On the other hand, he found efficient hydraulic ejection seats on the 2-seat Heinkel 219 night fighter. The crews of the unit which flew them had ejected from nine aeroplanes and all were successful without injury.

Eric was able to get into the Russian zone where he found a friendly major who let him fly a Lavochkin La-9. It had come into service in the latter days of the war and he found it to have an excellent performance though its construction was ‘very rough’.

He said that the Russian pilots were ‘very naïve’ about fighting tactics and relied on sheer numbers in combat. During the battle of Kursk, one of the greatest tank engagements of the war, the Russians lost 430 aircraft. German losses were 27.

One of the unusual aeroplanes tested was the Blohm und Voss Bv 141. Its odd design was intended to give the pilot a clear field of view and his gunner a wide field of fire rearwards. Eric said that when he was flying it he began to feel that he’d forgotten something.

In Norway he found a Blohm und Voss 222. Powered by six diesel engines, the centre engine on each wing had reversible pitch props for manoeuvring on the water. It was unusual in that the control surfaces were freely mounted. The stick and rudder in the cockpit were connected only to the trim tabs so they were very light to move and the controls became effective only with increasing airspeeds. Because the controls surfaces were free to flap about when the boat was moored they were held central by locks inside the aeroplane by the engineer’s station.

Having learned what he could about the boat, he thought it prudent to take a German technician, supervised by an RAF engineer, plus a reluctant German officer in the cockpit to help with the first take-off. Several miles of high-speed taxiing failed to produce lift-off and Eric realized that the elevator lock had been deliberately left on. He told his RAF colleague to remove the German from the engineer’s position at which the German officer joined in the argument with flying fists. A few well-timed blows settled the matter and the Germans were put ashore. Overall, Eric thought the Bv222 was a very impressive aeroplane.

What Eric’s team found showed that the Germans were far in advance of the Allies in their aerodynamic knowledge and research. As an example, whilst Britain had no supersonic wind tunnels, the Germans had nine, most of which could test up to Mach 1.2. There was a similar wind tunnel in Italy. And in Bavaria they found a tunnel that could test up to Mach 4.4.

Eric was given a vote of thanks by AVM John Allison (Chairman of Shuttleworth Trustees) who pointed out that the logbooks of Shuttleworth’s test pilots paled into insignificance beside Eric’s logbook. Eric corrected him – ‘twelve logbooks’.

Eric was given a vote of thanks by AVM John Allison (Chairman of Shuttleworth Trustees) who pointed out that the logbooks of Shuttleworth’s test pilots paled into insignificance beside Eric’s logbook. Eric corrected him – ‘twelve logbooks’.