Convair’s Mighty B-36 (July 2013)

The design was conceived as early as 1941 when the US saw a possible need for a bomber which could reach Berlin from a US or Canadian base. The project was given a boost in 1942 when raids on Tokyo from Hawaii became another possible requirement. However, the prototype did not fly until 1946, apparently too late for its planned use. But soon the Cold War ensured that the B-36 would earn a starring role. Its ability to carry nuclear bombs to targets 3,400 miles away made it the ultimate weapon of retaliation against any aggression by the Soviet Union.

The B-36 was BIG. Its four bomb bays could carry a load of 86,000 lbs. Its wingspan of 230’ (often quoted as exceeding the entire distance flown by Orville Wright in his first successful flight) overshadowed the 141’ of the B-29 and the 102’ of the puny Lancaster. The wing carried all the fuel and at the root it was seven and a half feet thick, Defensive armament was in eight turrets, each with two 20mm cannon.

Six 28-cylinder Pratt and Whitney Wasp Major engines producing 38,000 hp were buried in the wings driving 19’ diameter pusher propellers. Gears drove them at less than half engine speed to keep the prop tips below supersonic speeds. Nevertheless, the drone resembled a formation of amplified Harvards and allegedly could be heard – and still rattled windows - when the B-36 flew over at 40,000’. Later marks added a pair of GE-47 jet engines under the outer wings, normally used for take-off and combat speed.

The B-36 was BIG. Its four bomb bays could carry a load of 86,000 lbs. Its wingspan of 230’ (often quoted as exceeding the entire distance flown by Orville Wright in his first successful flight) overshadowed the 141’ of the B-29 and the 102’ of the puny Lancaster. The wing carried all the fuel and at the root it was seven and a half feet thick, Defensive armament was in eight turrets, each with two 20mm cannon.

Six 28-cylinder Pratt and Whitney Wasp Major engines producing 38,000 hp were buried in the wings driving 19’ diameter pusher propellers. Gears drove them at less than half engine speed to keep the prop tips below supersonic speeds. Nevertheless, the drone resembled a formation of amplified Harvards and allegedly could be heard – and still rattled windows - when the B-36 flew over at 40,000’. Later marks added a pair of GE-47 jet engines under the outer wings, normally used for take-off and combat speed.

The 15 crew were housed in two separate pressurized compartments linked by a tunnel passing through the bomb bays. Crew members could lie on a trolley and pull themselves through the 85’ tunnel, preferably when the aeroplane was in level flight. Typical missions were 15 or 20 hours long with occasional longer flights of up to 35 hours. These needed a relief crew to be carried in what was already cramped accommodation.

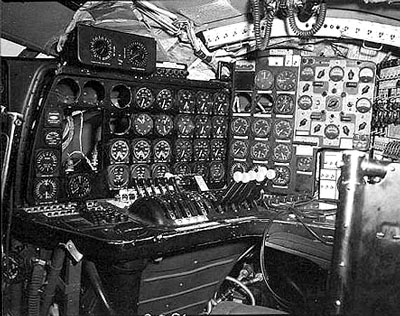

If you’d like to study some excellent pictures of the inside of a B-36 go tohttp://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/virtualtour/cockpits.asp and scroll down to Cold War Gallery.

The B-36 wings were based in Texas and New Mexico but since they were intended to ‘surround Russia’ there were frequent deployments to Europe, Japan and North Africa to ensure that other airfields could handle the B-36. Things didn’t always go smoothly.

In January 1952 Jim Connor flew his B-36 from Carswell AFB in Texas towards Boscombe Down for his first visit to England. A Wiltshire snowstorm hid the airfield and the bomber circled for some two hours. At last the crew were relieved to see the recently installed obstruction light on the spire of Salisbury Cathedral and then, a short distance away, the runway lights of the airfield. They started their approach.

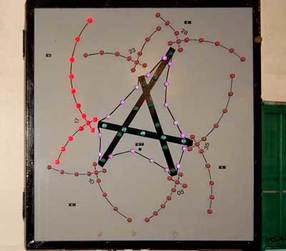

However, what they saw was a funnel of lights which led to the runway. They were part of the wartime Drem system that was still in use at Boscombe Down. The B-36 crew had experience solely of American airfield lighting in which only the runway was outlined in lights. They were therefore unfamiliar with and confused by lead-in lights.

The Boscombe Down controller said ‘You are two miles from touchdown, on centre line’. The pilot responded ‘I’ve landed’ and, after a slight pause, ‘My, isn’t your field rough’.

However, what they saw was a funnel of lights which led to the runway. They were part of the wartime Drem system that was still in use at Boscombe Down. The B-36 crew had experience solely of American airfield lighting in which only the runway was outlined in lights. They were therefore unfamiliar with and confused by lead-in lights.

The Boscombe Down controller said ‘You are two miles from touchdown, on centre line’. The pilot responded ‘I’ve landed’ and, after a slight pause, ‘My, isn’t your field rough’.

The B-36 had touched down in a field, ploughed through a fence, demolished a haystack and a shepherd’s hut, crossed a couple of ditches and the Amesbury-Salisbury road and ended 400 yards short of the airfield boundary fence.

The VHF/DF operator in his little hut near the end of the runway rang the tower to say there was an aeroplane outside his hut. He was told ‘We haven’t time to talk to you now. We’re waiting for a very important aircraft’. Meanwhile, the B-36 shut down all but one of the engines which was kept running to provide electrical power. A crew member shone a torch on the spinning blades to prevent anyone walking into it. A Boscombe Down staff member was driving home after a night out in Salisbury and stopped his car. He politely told a crew member ‘If you want the airfield it’s over there’ and drove off.

The VHF/DF operator in his little hut near the end of the runway rang the tower to say there was an aeroplane outside his hut. He was told ‘We haven’t time to talk to you now. We’re waiting for a very important aircraft’. Meanwhile, the B-36 shut down all but one of the engines which was kept running to provide electrical power. A crew member shone a torch on the spinning blades to prevent anyone walking into it. A Boscombe Down staff member was driving home after a night out in Salisbury and stopped his car. He politely told a crew member ‘If you want the airfield it’s over there’ and drove off.

Despite the embarrassment, some redeeming features emerged. It was a cold night and the ground was frozen hard and it had easily taken the weight of the bomber. The next morning, a bulldozer borrowed from the construction workers who were building the airfield at Greenham Common scraped off the thin topsoil revealing the hard chalk beneath. The B-36 was towed through a gap opened up in the perimeter fence. Boscombe Down engineers made a new bolt to substitute the broken one in the port undercarriage and the propeller damaged by the shepherd’s hut was replaced.

Before the exercise, General Curtis LeMay had told the pilots that if anyone damaged their aircraft they could walk east until their caps floated and then carry on walking. As it was, the B-36 was safely flown home within two days. Jim Connor, apparently demoted from Colonel to Lieutenant in a phone call by LeMay himself, rode as a passenger with the gunners in the back.

Before the exercise, General Curtis LeMay had told the pilots that if anyone damaged their aircraft they could walk east until their caps floated and then carry on walking. As it was, the B-36 was safely flown home within two days. Jim Connor, apparently demoted from Colonel to Lieutenant in a phone call by LeMay himself, rode as a passenger with the gunners in the back.