Brainfade over Brazil (Aug 2018)

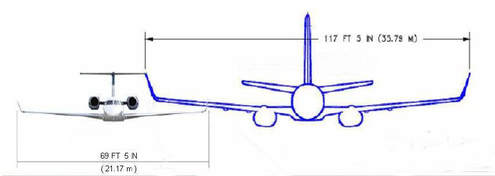

It sounded like an interesting assignment. Joseph Lepore, a 42 year old airline pilot, was scheduled to collect a new jet from Brazil. He worked for ExcelAire, a Long Island based aircraft management company who hired out jets as global air taxis. Their new acquisition was a Legacy 600, built by Embraer in São Paulo, Brazil. His co-pilot would be 34 year old Jan Paul Paladino who had worked for ExcelAire for just a month but had previous experience of flying earlier models of Embraer jets.

With two vice-presidents of the company they flew down to São Paulo for a final inspection of the shining Legacy bearing the appropriate registration N600XL. Minor snags needed fixing and by the time they were ready to leave they had acquired two more passengers, Henry Yandle, Embraer’s North American sales rep and Joe Sharkey, a Business Travel journalist who had been doing a story on another Embraer model.

With two vice-presidents of the company they flew down to São Paulo for a final inspection of the shining Legacy bearing the appropriate registration N600XL. Minor snags needed fixing and by the time they were ready to leave they had acquired two more passengers, Henry Yandle, Embraer’s North American sales rep and Joe Sharkey, a Business Travel journalist who had been doing a story on another Embraer model.

The flight plan was prepared from Embraer’s airfield at São José dos Campos to Manaus on the Amazon. Airway UZ5 would take them to Brasilia when they would turn to join UZ6. To suit the jet’s performance and the winds they elected to fly at 37,000 ft. That particular height was chosen because of a rule introduced to prevent conflict between two aircraft following the same airway in different directions. Any aircraft on a course east of north or south is required to fly at an altitude which is an odd number of thousands of feet e.g. 33,000, 35,000, 37,000 and so on. Aircraft flying in the opposite direction on a course west of north or south would fly at even thousands. The map shown is not correctly oriented north-south. The course to follow UZ5 from São José dos Campos to Brasilia is actually 032 ° i.e. east of north, hence the pilots’ choice of 37,000.

Any aircraft flying from Brasilia to São José on UZ5 would be on the reciprocal course of 212°, i.e. west of north, so they would be allocated 36,000 or 38,000ft.

With the flight plan accepted and their height of 37,000 ft (or Flight Level 370) approved the Legacy was given a unique transponder code which they set on their panel. The transponder is a radio beacon which answers air traffic radar with a signal which displays the altitude of the aeroplane on the controller’s panel. It was 2.51 pm on 29 September 2006 when Lepore powered up the twin 7,900 lbs thrust Rolls Royce engines and the Legacy smoothly left the ground.

What happened later was recorded in detail by the cockpit voice recorder whose looped tape records two hours of cockpit conversation and noise. 42 minutes into the flight the Legacy was comfortably in cruise and being flown by the auto-pilot. Paladino was on the radio checking in to a new air traffic control sector. Brazilian air traffic is controlled by the military and whilst the international language of aviation is English, not all controllers are fluent since, for internal traffic in Brazil, they just use Portuguese. Paladino said ‘N600XL level. Flight Level 370’. The reply was garbled and incoherent. The second try was little better. Lepore said ‘I think he said radar contact’. Paladino spoke to the radio ‘Roger. Radar contact’ and to Lepore ‘I’ve no idea what he said’. They left it at that.

Paladino picked up the laptop provided by Embraer loaded with Legacy flight planning software. There was the occasional curse when he lost a page and a background of message exchanges of Portuguese on the radio. Someone came into the cockpit and asked how much longer it would be before landing. They tried to find it on the Flight Management System, looking for ‘Arrival Time’ and other variations. It was not immediately obvious but finally emerged under ‘Time Remaining’.

The pilots continued exploring the buttons until they approached the turn point at Brasilia. The controller gave them the new frequency and they checked in. ‘N600XL level, Flight Level 370. Good afternoon’. The controller, Sergeant dos Santos, replied ‘N600XL squawk ident. Radar surveillance’. ‘Squawk ident’ is a request to activate the transponder and it is not clear why the controller asked for this since the sector was unusually quiet at the time. Paladino briefly neglected to take any action then remembered and pushed the button. Suddenly the communications frequency disappeared. However, Paladino had written it down and was able to restore it.

The two men turned their attention to Manaus and began calculating the landing distance and also the take-off distance required for departure the following day. Without comment from the pilots, the autopilot turned the Legacy onto the new course for airway UZ6, 336°. This was west of north and the rules of separation required them to be at an even height, 36,000’. But this change had to be approved by the controller and the pilots had to stay at 37,000’ until told to descend. They made no comment about it, nor did the controller.

Controllers' panels have two blocks to indicate an aircraft’s height. One shows the transponder’s figure, the actual height, and the other is entered manually by the controller to show the height to which an aircraft has been cleared. Its progress to reach that can be monitored by comparing the two figures. When they match an = symbol appears. In Brazil it was slightly different. If no manual entry had been made in the second block the computer reverted to showing the figure entered in the flight plan. Now, in front of Sgt dos Santos were two indications of the Legacy’s height – 37,000’ and 36,000’. If he noticed the difference he did nothing about it.

Then, at 4.02 pm, the Legacy’s transponder stopped transmitting. It did it automatically, possibly because one of the pilots had, either deliberately or accidentally, touched the wrong button or knocked it with the corner of the laptop's screen. For the failure of such an important instrument the system provided no warning, no blinking light or beeping signal. The ‘On’ indicator merely changed to ‘Standby’. On dos Santos’s screen a ‘Z’ appeared alongside the altitude indicators- and like the ‘Standby’ indication in the cockpit went quite unnoticed.

Fifteen minutes later, dos Santos went off duty, handing over to Sgt de Alencar. His briefing he included the Legacy but the altitude differences and the ‘Z’ symbol were not mentioned. (At the same time the jet was being automatically tracked by another Air Force radar not part of the air traffic system. This had a fairly crude height detection device. When the Legacy was overhead the radar recorded FL 370 correctly but as it moved away from the vertical the recordings varied wildly. These records were examined later in the inquiry and led to accusations that the Legacy had been ‘stunting’).

Ten minutes after coming on duty de Alencar tried to contact the Legacy. The increasing range was making the communication unreliable and his calls were unheard in the Legacy cockpit. He kept on calling at intervals, for the next 26 minutes. He could have asked another aircraft to relay his message but didn’t think his English was good enough. Instead he got his assistant to call Manaus to warn them that there was an aeroplane approaching, at 36,000’. There was no mention that the transponder had failed and that the Legacy had flown 500 miles since the last radio contact.

The failure of the transponder had affected another system. The Traffic Collision Avoidance System talks to other transponders and warns pilots of any close aircraft, even issuing instructions for one to climb and another to descend. Again, there was no warning chime or buzzer when the TCAS went down. The Legacy was flying along the centre line of an active airway at the wrong height, invisible to others and its pilots were completely unaware of the danger they were in or were posing to others.

They did begin to wonder about the lack of contact though. Paladino dug out a printed high altitude navigation chart and in the blizzard of numbers found list of six radio frequencies. He gave each one two calls. Maybe some of his calls had been blocked by a transmission from another aircraft but he failed to get any response. By a fluke he left the radio on the last frequency he had tried and it was used by de Alencar on one of his attempts to establish communication. ‘N600XL, contact Amazonia Center 123.32. If unable 126.45. N600XL.’ Paladino was taken by surprise. ‘What was that frequency 1.2.3.. I didn’t get the last two ..’. There was no answer.

What happened later was recorded in detail by the cockpit voice recorder whose looped tape records two hours of cockpit conversation and noise. 42 minutes into the flight the Legacy was comfortably in cruise and being flown by the auto-pilot. Paladino was on the radio checking in to a new air traffic control sector. Brazilian air traffic is controlled by the military and whilst the international language of aviation is English, not all controllers are fluent since, for internal traffic in Brazil, they just use Portuguese. Paladino said ‘N600XL level. Flight Level 370’. The reply was garbled and incoherent. The second try was little better. Lepore said ‘I think he said radar contact’. Paladino spoke to the radio ‘Roger. Radar contact’ and to Lepore ‘I’ve no idea what he said’. They left it at that.

Paladino picked up the laptop provided by Embraer loaded with Legacy flight planning software. There was the occasional curse when he lost a page and a background of message exchanges of Portuguese on the radio. Someone came into the cockpit and asked how much longer it would be before landing. They tried to find it on the Flight Management System, looking for ‘Arrival Time’ and other variations. It was not immediately obvious but finally emerged under ‘Time Remaining’.

The pilots continued exploring the buttons until they approached the turn point at Brasilia. The controller gave them the new frequency and they checked in. ‘N600XL level, Flight Level 370. Good afternoon’. The controller, Sergeant dos Santos, replied ‘N600XL squawk ident. Radar surveillance’. ‘Squawk ident’ is a request to activate the transponder and it is not clear why the controller asked for this since the sector was unusually quiet at the time. Paladino briefly neglected to take any action then remembered and pushed the button. Suddenly the communications frequency disappeared. However, Paladino had written it down and was able to restore it.

The two men turned their attention to Manaus and began calculating the landing distance and also the take-off distance required for departure the following day. Without comment from the pilots, the autopilot turned the Legacy onto the new course for airway UZ6, 336°. This was west of north and the rules of separation required them to be at an even height, 36,000’. But this change had to be approved by the controller and the pilots had to stay at 37,000’ until told to descend. They made no comment about it, nor did the controller.

Controllers' panels have two blocks to indicate an aircraft’s height. One shows the transponder’s figure, the actual height, and the other is entered manually by the controller to show the height to which an aircraft has been cleared. Its progress to reach that can be monitored by comparing the two figures. When they match an = symbol appears. In Brazil it was slightly different. If no manual entry had been made in the second block the computer reverted to showing the figure entered in the flight plan. Now, in front of Sgt dos Santos were two indications of the Legacy’s height – 37,000’ and 36,000’. If he noticed the difference he did nothing about it.

Then, at 4.02 pm, the Legacy’s transponder stopped transmitting. It did it automatically, possibly because one of the pilots had, either deliberately or accidentally, touched the wrong button or knocked it with the corner of the laptop's screen. For the failure of such an important instrument the system provided no warning, no blinking light or beeping signal. The ‘On’ indicator merely changed to ‘Standby’. On dos Santos’s screen a ‘Z’ appeared alongside the altitude indicators- and like the ‘Standby’ indication in the cockpit went quite unnoticed.

Fifteen minutes later, dos Santos went off duty, handing over to Sgt de Alencar. His briefing he included the Legacy but the altitude differences and the ‘Z’ symbol were not mentioned. (At the same time the jet was being automatically tracked by another Air Force radar not part of the air traffic system. This had a fairly crude height detection device. When the Legacy was overhead the radar recorded FL 370 correctly but as it moved away from the vertical the recordings varied wildly. These records were examined later in the inquiry and led to accusations that the Legacy had been ‘stunting’).

Ten minutes after coming on duty de Alencar tried to contact the Legacy. The increasing range was making the communication unreliable and his calls were unheard in the Legacy cockpit. He kept on calling at intervals, for the next 26 minutes. He could have asked another aircraft to relay his message but didn’t think his English was good enough. Instead he got his assistant to call Manaus to warn them that there was an aeroplane approaching, at 36,000’. There was no mention that the transponder had failed and that the Legacy had flown 500 miles since the last radio contact.

The failure of the transponder had affected another system. The Traffic Collision Avoidance System talks to other transponders and warns pilots of any close aircraft, even issuing instructions for one to climb and another to descend. Again, there was no warning chime or buzzer when the TCAS went down. The Legacy was flying along the centre line of an active airway at the wrong height, invisible to others and its pilots were completely unaware of the danger they were in or were posing to others.

They did begin to wonder about the lack of contact though. Paladino dug out a printed high altitude navigation chart and in the blizzard of numbers found list of six radio frequencies. He gave each one two calls. Maybe some of his calls had been blocked by a transmission from another aircraft but he failed to get any response. By a fluke he left the radio on the last frequency he had tried and it was used by de Alencar on one of his attempts to establish communication. ‘N600XL, contact Amazonia Center 123.32. If unable 126.45. N600XL.’ Paladino was taken by surprise. ‘What was that frequency 1.2.3.. I didn’t get the last two ..’. There was no answer.

There was another aeroplane using UZ6. Gol’s internal flight to Rio de Janiero had left Manaus at 3.35 that afternoon carrying six crew members and 148 passengers. On a course of 156° i.e. east of south, it was cruising at an odd i.e. correct altitude, 37,000’. The captain was 44 year old Decio Chaves who had logged 14,900 hours in flight, his 29 year old co-pilot, Thiago Cruso a mere 3,850 hours. Their brand new Boeing 737 was less than a month old.

They had just crossed an air traffic sector boundary and had changed frequencies, bizarrely hearing de Alencar’s last message to the Legacy. Their TCAS was clear. There was no evidence of anything else in the sky.

They didn’t look out of the window and even if they had it’s highly unlikely that would have seen the slim silhouette of the Legacy approaching head on at a closing speed of more than 1000 mph.

They had just crossed an air traffic sector boundary and had changed frequencies, bizarrely hearing de Alencar’s last message to the Legacy. Their TCAS was clear. There was no evidence of anything else in the sky.

They didn’t look out of the window and even if they had it’s highly unlikely that would have seen the slim silhouette of the Legacy approaching head on at a closing speed of more than 1000 mph.

An airway is 10 miles wide and aeroplanes don’t have to follow the centre line. Over the years the accuracy of systems using satellites has increased dramatically. If the equipment fitted to the two aeroplanes had been less precise they would have passed each other unnoticed. As it was, the noses of the Legacy and the Boeing were only seventy feet apart. And had the Legacy been just ten feet lower they would merely have wobbled in each other’s turbulence. In the event, the wing tip of the Boeing tore the tip of the tailplane and elevator of the smaller jet.

But it was the winglet of the Legacy which had such a lethal effect. Like a scalpel, it sliced through the Boeing’s wing and mainspar. The outer third of the wing broke off and whirled through the tail demolishing much of it.

The Boeing rolled to the left and pitched into a rotating plunging dive. What is remarkable is how controlled the pilots were. Apart from the repeated robotic call ‘Bank angle! Bank angle! almost the only word uttered , twice, was ‘Calma’ (Stay calm). The undercarriage was lowered in an attempt try to slow the fall. Twenty two seconds after the collision the overspeed warning began its clamour and at thirty seconds 4G was exceeded. At fifty two seconds the tortured wreckage broke into three parts at 7,000’ and everything sank into the forest.

In the Legacy the sharp sound of the crash was followed by a grunt from Lepore as if he had been punched. With a three chime warning the autopilot disengaged and the Legacy rolled to the left. Lepore levelled the plane, needing to keep the yoke well to the right to hold it steady. Paladino checked the pressurisation and confirmed that there had not been an explosive depressurisation. A passenger came into the cockpit and said ‘You know we lost a winglet’.

In the Legacy the sharp sound of the crash was followed by a grunt from Lepore as if he had been punched. With a three chime warning the autopilot disengaged and the Legacy rolled to the left. Lepore levelled the plane, needing to keep the yoke well to the right to hold it steady. Paladino checked the pressurisation and confirmed that there had not been an explosive depressurisation. A passenger came into the cockpit and said ‘You know we lost a winglet’.

Paladino had more experience with Embraer jets than Lepore and took over the controls. He reduced power and began a descent. As well as the loss of the winglet the whole wing had been bent slightly upwards. Lepore looked for the frequency to declare an emergency. Paladino found the button on the Flight Management System which gave them the code for the nearest airfield, SBCC, just 100 miles ahead.

The discussion about what had happened went on ‘Did we hit somebody? Did you see anything?’ Then, there was an audible gasp. Paladino asked ‘Did we have the TCAS on?’ Lepore said ‘Yes… The TCAS is off’. It was promptly switched on without any recorded comment.

SBCC is a military airfield called Cachimbo. A Boeing 747 cargo plane had answered Lepore’s emergency call and was relaying what information it could get for Cachimbo. Paladino was experimenting with the Legacy’s handling and found that control was difficult below 230 mph. He was happy to learn that the runway seemed to be long enough for their landing, inevitably it would be at high speed. It took a long time for Manaus control to provide the frequency for Cachimbo tower and almost as long to get the controller there to accept that the Legacy was going to land, permission or not.

They descended into the murk of the Amazonian land clearance fires, crossed the threshold at 200+ mph amid the noise of various insistent cockpit alarms and with very heavy braking rolled to a stop. The relieved cabin occupants clapped and cheered.

The exchanged impressions of the event came to the conclusion that they must have hit another aeroplane. What else could it be? How could it be? That evening, whilst they were having dinner, the news came through that a Boeing was missing.

An English speaking Brazilian official rang from Manaus to speak to the Legacy’s captain. Lepore took the call. He confirmed that the collision happened about 100 miles from Cachimbo when the Legacy was flying level at 37,000’. The official asked ‘Level at 370?’

‘Level at 370’, confirmed Lepore. ‘O.K. And the TCAS was on?’ Lepore said ‘No’.

‘No TCAS?’ Another voice can be heard in the background of the recording insisting that the TCAS was on. Lepore said ‘The TCAS was on’.

‘O.K. was on. But no signal was reported’. ‘No. We didn’t get any warning’.

The discussion about what had happened went on ‘Did we hit somebody? Did you see anything?’ Then, there was an audible gasp. Paladino asked ‘Did we have the TCAS on?’ Lepore said ‘Yes… The TCAS is off’. It was promptly switched on without any recorded comment.

SBCC is a military airfield called Cachimbo. A Boeing 747 cargo plane had answered Lepore’s emergency call and was relaying what information it could get for Cachimbo. Paladino was experimenting with the Legacy’s handling and found that control was difficult below 230 mph. He was happy to learn that the runway seemed to be long enough for their landing, inevitably it would be at high speed. It took a long time for Manaus control to provide the frequency for Cachimbo tower and almost as long to get the controller there to accept that the Legacy was going to land, permission or not.

They descended into the murk of the Amazonian land clearance fires, crossed the threshold at 200+ mph amid the noise of various insistent cockpit alarms and with very heavy braking rolled to a stop. The relieved cabin occupants clapped and cheered.

The exchanged impressions of the event came to the conclusion that they must have hit another aeroplane. What else could it be? How could it be? That evening, whilst they were having dinner, the news came through that a Boeing was missing.

An English speaking Brazilian official rang from Manaus to speak to the Legacy’s captain. Lepore took the call. He confirmed that the collision happened about 100 miles from Cachimbo when the Legacy was flying level at 37,000’. The official asked ‘Level at 370?’

‘Level at 370’, confirmed Lepore. ‘O.K. And the TCAS was on?’ Lepore said ‘No’.

‘No TCAS?’ Another voice can be heard in the background of the recording insisting that the TCAS was on. Lepore said ‘The TCAS was on’.

‘O.K. was on. But no signal was reported’. ‘No. We didn’t get any warning’.

That conversation led to the decision of the Brazilian government to bring charges against the Legacy pilots for reckless flying. They were held in Brazil for over two months until a court ruled they could be released pending the outcome of the accident investigation. They signed a document promising to return to Brazil when required and went home to the USA and resumed their flying jobs with ExcelAire.

The search for the Boeing was protracted. There had been few witnesses of the crash and the forest canopy had closed over the wreckage so the searching helicopters could find nothing. It wasn’t until the Brazilian Air Force provided a Hercules with MAD equipment that the metal parts were detected and the gruesome task of recovering the 154 bodies could begin.

The search for the Boeing was protracted. There had been few witnesses of the crash and the forest canopy had closed over the wreckage so the searching helicopters could find nothing. It wasn’t until the Brazilian Air Force provided a Hercules with MAD equipment that the metal parts were detected and the gruesome task of recovering the 154 bodies could begin.

The accident investigation was thorough and uncovered all the errors and omissions. The Brazilian (CENIPA) report accorded blame to both the air traffic system and the Legacy pilots. A separate US (NTSB) report implied that the pilots were more victims of circumstance than offenders. Recommendations were made that warnings of the failure of important systems should be more prominent.

Matters became overshadowed by another serious crash in Brazil in 2007 which claimed 199 lives and brought the ATC system into serious disrepute. It triggered what became known as the Brazilian aviation crisis and a defence minister was fired. Charges against Honeywell for the lack of warning for TCAS failure and private prosecution of the pilots by relatives of some of the victims in the Boeing came to naught.

The final outcome for Lepore and Paladino was that in 2015, nine years after the event, they were sentenced to loss of licence (which the FAA insists cannot be enforced in the USA) and 4 years and 4 months served in an ‘open regime’ (which can be served in the USA by regular reporting to the authorities. Sgt. de Alencar was found guilty of incompetence and sentenced to 40 months, served in an open regime.

The Legacy? It sat on the naughty step until 2011 when it was repaired and repolished. In 2013 it was sold, re-registered and is flying again in Mexico.

Matters became overshadowed by another serious crash in Brazil in 2007 which claimed 199 lives and brought the ATC system into serious disrepute. It triggered what became known as the Brazilian aviation crisis and a defence minister was fired. Charges against Honeywell for the lack of warning for TCAS failure and private prosecution of the pilots by relatives of some of the victims in the Boeing came to naught.

The final outcome for Lepore and Paladino was that in 2015, nine years after the event, they were sentenced to loss of licence (which the FAA insists cannot be enforced in the USA) and 4 years and 4 months served in an ‘open regime’ (which can be served in the USA by regular reporting to the authorities. Sgt. de Alencar was found guilty of incompetence and sentenced to 40 months, served in an open regime.

The Legacy? It sat on the naughty step until 2011 when it was repaired and repolished. In 2013 it was sold, re-registered and is flying again in Mexico.