Who Really was the First to Fly? (March 2023)

Ask a group of, say, visitors to Shuttleworth ‘Who was the first to fly?’ and someone will come up with the ’Wright brothers’. They might know little else about aviation but that one little gem of knowledge seems to be widespread - a significant event which was witnessed, recorded and photographed. Other groups could react differently. The question might provoke a discussion on what is meant by ‘fly’. Balloonists have been ‘flying’, or floating, since 1783 and what about all those chaps who made the first hang gliders in the 19th century. There’d be no discussion if the group were all Brazilians. They just know the answer is - Alberto Santos Dumont. They named an airport after him. And you could find a select group of New Zealanders who champion the cause of Richard Pearse. Then there are those Americans who are not sure you can dismiss the claims of Gus Whitehead.

No one can dismiss the extensive research and experiments of Sir George Cayley, which culminated in the flights of a glider carrying a 10 year old boy and, later, one of Sir George’s employees in 1853. A truly significant event.

No one can dismiss the extensive research and experiments of Sir George Cayley, which culminated in the flights of a glider carrying a 10 year old boy and, later, one of Sir George’s employees in 1853. A truly significant event.

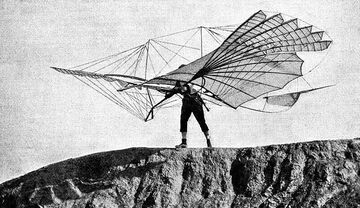

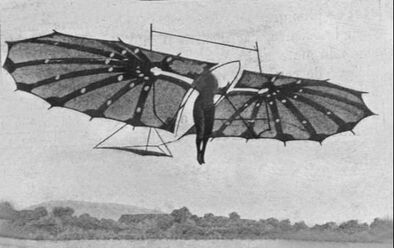

Unlike modern hang gliders where the pilot sits in a swinging seat so that his whole body weight can be moved to control the glider, Otto grasped the glider with his arms in slots. He could swing only his legs to counter any turn and, more critically, unwanted climbs and dives.

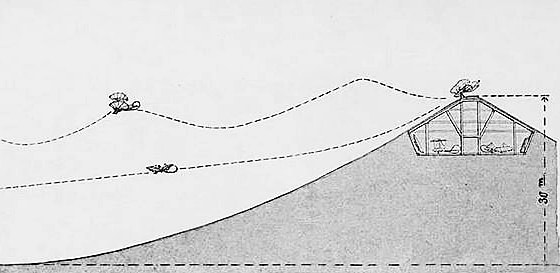

He did occasional tests with control surfaces, principally a small elevator to make gentler landings. (it’s believed that he pulled a string/wire to operate this and the string was attached to a headband - so a timely nod lightened his touchdown. He didn’t use it much). The ‘elevator’ wasn’t fitted when he took his biplane glider to the Rhinow hills. He had three successful flights - in one he covered 250 metres. On the fourth flight the glider ‘pitched forward’ (stalled?} and Otto could not recover from the dive. He crashed to the ground and his back was broken. He died in hospital the next day.

Does this astonishing record of more than 2000 glides over a period of five years make him ‘first to fly’. Hmm. Cayley’s coachman is still first by a long way but he was just a passenger, ballast, by no means a pilot. And Otto wasn’t the only gliding pioneer

Does this astonishing record of more than 2000 glides over a period of five years make him ‘first to fly’. Hmm. Cayley’s coachman is still first by a long way but he was just a passenger, ballast, by no means a pilot. And Otto wasn’t the only gliding pioneer

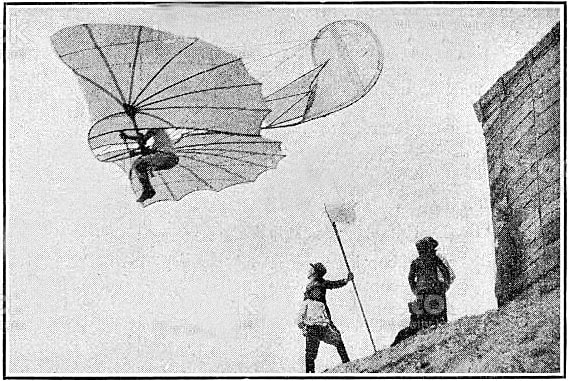

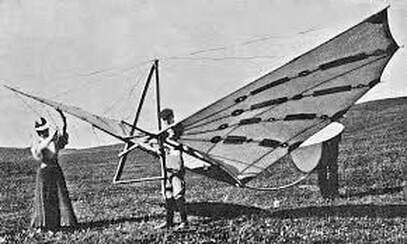

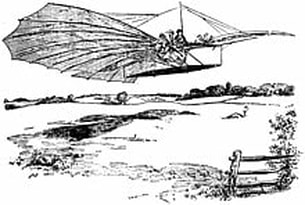

Percy built more gliders, the Beetle and the Gull and, finally, the Hawk. This is the Hawk, being flown, not by Percy but by Dorothy, his cousin. (The other lady in his team was Ella, his sister - she’s in the picture (above) with the Bat. Ella’s sewing machine crafted the wing coverings for all Percy’s gliders and she was always involved in the flying.

Although there’s no traceable evidence that Ella flew one of the gliders it’s got to be highly likely that she did. There’s another significant event - the first women . . . .).

The Pall Mall Gazette reporter covering the event made more fuss about Dorothy's knocking over his colleague’s movie camera at the bottom of the hill than the fact that there was actual flying going on and that the flyer was a woman (!).

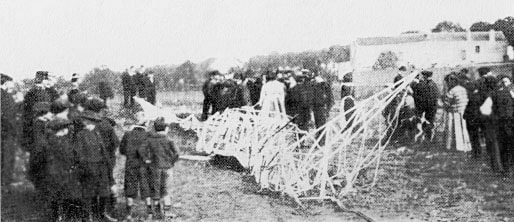

Percy teamed up with Walter Gordon Wilson, a motor engineer, and they built an engine - 4 hp - just enough to power a flying machine. Percy had built a biplane glider and enlarged the design to a triplane to carry all that extra weight. He arranged a demonstration at Stanford Hall (Leicestershire) hoping to raise some sponsorship money. Unfortunately, when he was testing the engine before the visitors arrived the crankshaft broke. So, on the day, 30th September 1899, he couldn’t fly his triplane. He had to show them something, so he got out the Hawk. To launch his gliders, Percy relied on real horse power. He laid out a rope across the field with the glider at the downwind end and at the other, a series of pulleys. When Dobbin walked one yard, Percy’s glider covered seven. It had been a very wet weekend and maybe the woodwork was a bit soggy. And the wind was rather gusty. Whatever the cause, the tail, attached to a single rod, broke and Percy plunged to the ground. He never regained consciousness and three days later, died.

Percy teamed up with Walter Gordon Wilson, a motor engineer, and they built an engine - 4 hp - just enough to power a flying machine. Percy had built a biplane glider and enlarged the design to a triplane to carry all that extra weight. He arranged a demonstration at Stanford Hall (Leicestershire) hoping to raise some sponsorship money. Unfortunately, when he was testing the engine before the visitors arrived the crankshaft broke. So, on the day, 30th September 1899, he couldn’t fly his triplane. He had to show them something, so he got out the Hawk. To launch his gliders, Percy relied on real horse power. He laid out a rope across the field with the glider at the downwind end and at the other, a series of pulleys. When Dobbin walked one yard, Percy’s glider covered seven. It had been a very wet weekend and maybe the woodwork was a bit soggy. And the wind was rather gusty. Whatever the cause, the tail, attached to a single rod, broke and Percy plunged to the ground. He never regained consciousness and three days later, died.

Percy is the quintessential might-have-been. In 2003 Cranfield University carried out the research to build a replica of the triplane and its engine. They made it as close as possible to the original design with some minor amendments, which they believed Percy himself would have made. The BBC produced a programme, the highlight of which is the Pilcher Triplane cruising across Cranfield airfield in full control. Now, that would have been a really significant event.

Gustave Whitehead (born in Bavaria in 1874 as Gustav Weisskopf) was an engineer who had experimented all his life with flying machines. An article appeared in the Bridgeport Herald in August 1901. It was an ‘eyewitness report’ (although it was unsigned and later proved to have been written by one of the paper’s journalists, who also did the drawing) of a ‘half mile’ powered flight made by Whitehead at Fairford, Connecticut on 14th August, 1901. The article was syndicated and appeared in many other newspapers, including Scientific American. Gustave went on experimenting and making other aeroplanes and ornithopters right until his death in 1927. Despite extensive research no one has uncovered any real evidence or photograph proving that he ever flew any of the aircraft he built.

Photographs, discovered after the article was published, of Gustave and his 1901 No.21.

Richard Pearse ran a small sheep farm in New Zealand but spent much of his time working as a mechanical engineer. He invented, and patented, a bicycle with self-inflating tires and soon moved on to engines and flying machines. He worked on, and finally patented in 1906, improvements to his flying machine and although it’s quite difficult to decipher in this drawing that accompanied the patent application, in there is a fabric covered bamboo monoplane , a tractor engine, tricycle undercarriage and no tail unit. The model built for a 1977 exhibition helps a little.

Asssertions that Pearse had flown before the Wright brothers began to emerge during the First World War. One witness could remember seeing the aeroplane flying - ‘it may have been 12 feet high at the time’- before crashing into a hedge. This was, purportedly, on 31st March 1903 i.e. nine month before the Wrights flew. Another young man, who was aged seven at the time, remembers seeing it rise to 60 feet and fly two and a half circuits of the field. Pearse himself tried to calm things down. He felt that no-one person should be credited with having invented the aeroplane, so many people were working on it - but it was the Wright brothers who first flew successfully.

That didn’t stop the ‘witnesses’. Richard Pearse’s great nephew assembled 48 eyewitness accounts of ‘aircraft work’ by Pearse and his attempted flights between 1902 and 1904. He said,‘48 is too high a number for all to be misled, misinformed, over-imaginative, senile, lying or stupid’. Museums across New Zealand display examples of Pearse’s engineering and in a lakeside town there lies a row of tiles listing important historic world and New Zealand events. The 1903 tile says that the first powered flight in history occurred in Timaru, NZ and at the bottom of the tile for 1903 the Wright Brothers were listed as having also flown that year.

That didn’t stop the ‘witnesses’. Richard Pearse’s great nephew assembled 48 eyewitness accounts of ‘aircraft work’ by Pearse and his attempted flights between 1902 and 1904. He said,‘48 is too high a number for all to be misled, misinformed, over-imaginative, senile, lying or stupid’. Museums across New Zealand display examples of Pearse’s engineering and in a lakeside town there lies a row of tiles listing important historic world and New Zealand events. The 1903 tile says that the first powered flight in history occurred in Timaru, NZ and at the bottom of the tile for 1903 the Wright Brothers were listed as having also flown that year.

In the case of Santos-Dumont the is no need to rely on witnesses’ memories. Everything is documented and photographed.

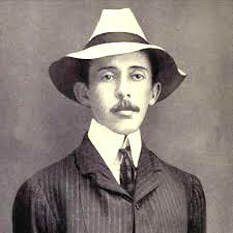

Alberto (1873-1932) was the son of a rich Brazilian coffee grower. Always fascinated by things mechanical from an early age, he studied at an engineering college but was not a good student - he did only what interested him. He travelled widely in his youth, America, England and Europe before settling in France in 1897 when he inherited ‘a fortune’ at the age of 24. He enjoyed practical rather than theoretical engineering. Always smartly dressed and with impeccable manners it was unusual to see him involved in greasy motor racing.

Alberto (1873-1932) was the son of a rich Brazilian coffee grower. Always fascinated by things mechanical from an early age, he studied at an engineering college but was not a good student - he did only what interested him. He travelled widely in his youth, America, England and Europe before settling in France in 1897 when he inherited ‘a fortune’ at the age of 24. He enjoyed practical rather than theoretical engineering. Always smartly dressed and with impeccable manners it was unusual to see him involved in greasy motor racing.

He hired professional aeronauts to teach him ballooning and here he is making his first ascent on 23rd March 1898.

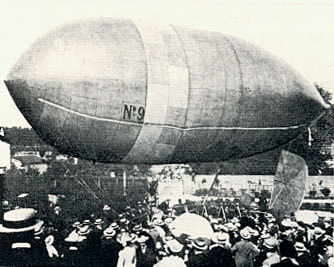

He built a series of balloons, nine of them in less than two years, and frequently took passengers for their first flights. He was awarded a prize by the French Aero Club for his study of atmospheric currents.

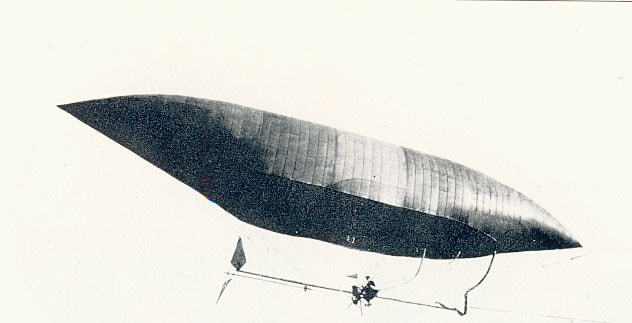

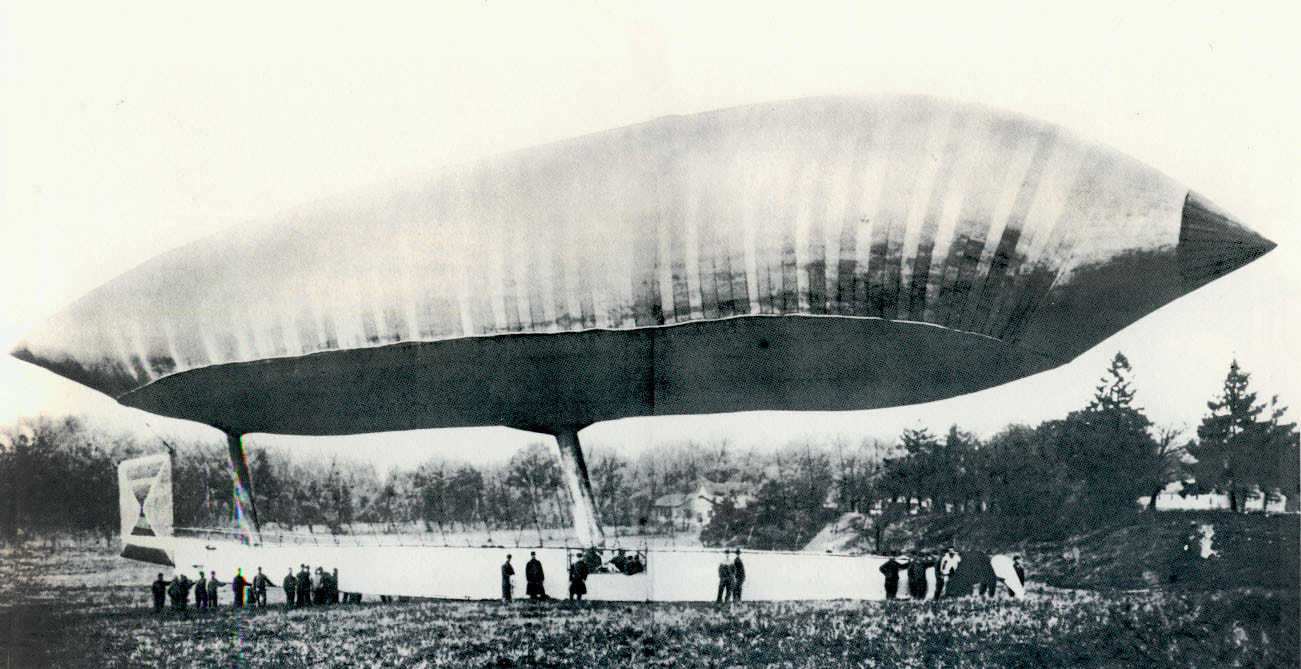

He turned his attention to dirigibles. The dirigible (meaning steerable) had been around for many years. Some early balloonists took up ‘oars’ to row through the sky - which were quite useless. It was only when they fitted an engine - steam, electric or petrol - that they made any progress. The spherical balloon had to be streamlined to give it direction so a sausage-shaped envelope was used. But if this is pushed through the air it would collapse unless the pressure inside the airship is greater than the outside pressure.

He built a series of balloons, nine of them in less than two years, and frequently took passengers for their first flights. He was awarded a prize by the French Aero Club for his study of atmospheric currents.

He turned his attention to dirigibles. The dirigible (meaning steerable) had been around for many years. Some early balloonists took up ‘oars’ to row through the sky - which were quite useless. It was only when they fitted an engine - steam, electric or petrol - that they made any progress. The spherical balloon had to be streamlined to give it direction so a sausage-shaped envelope was used. But if this is pushed through the air it would collapse unless the pressure inside the airship is greater than the outside pressure.

Thus, inside the envelope will be one, or more, gasbags containing the hydrogen, surrounded by ambient air which must be pressurised. The little engine would have to work harder, driving an air pump as well as the propeller. (In larger ships they used specially shaped air bags, called ballonets, which press against the outer skin. Larger still airships were fitted with a wood or metal frame - semi-rigid - and, Zeppelin sized, a complete frame - rigid.

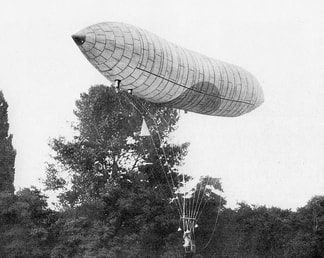

Santos Dumont had a small dirigible built by Henri Lachambre. Made of lightweight Japanese silk it was powered by a 4 hp De Dion Bouton engine. It soon proved to be too lightweight and it folded. The air pump was too weak to keep the envelope pressurised and the ship began to fold and descend rapidly. S D could have been injured or even killed in the crash. He called to passers-by to catch the trail rope and pull it into the wind. It worked and the ship sank down into some convenient trees which broke its fall. Alberto emerged unharmed. He commented drily ‘I have varied my amusement: I went up in a balloon and came down in a kite’.

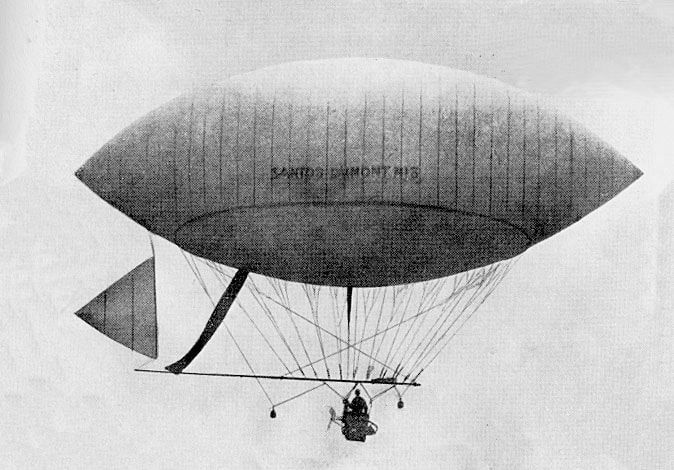

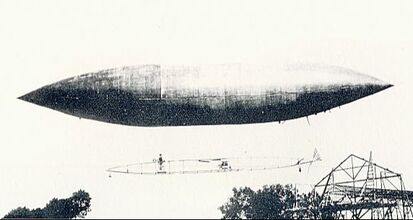

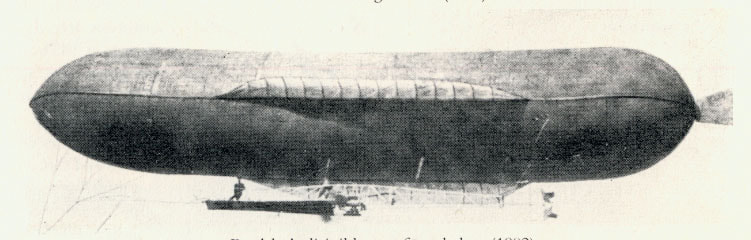

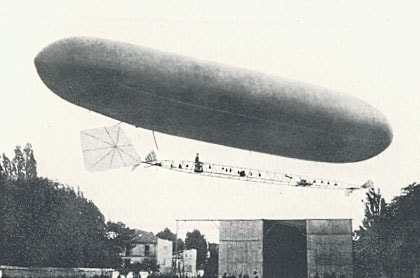

Other dirigibles followed. This is No. 3 … …and No 4. S D is sitting on a bicycle saddle.

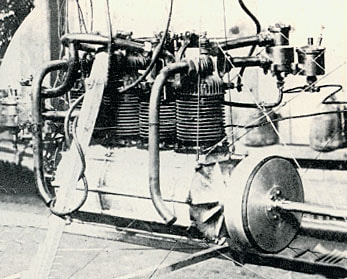

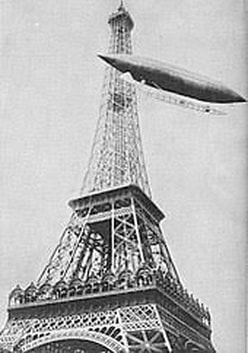

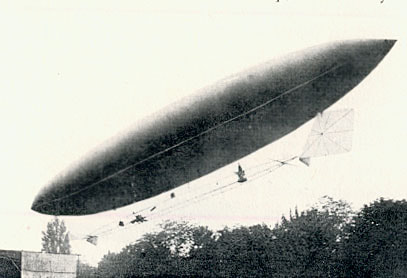

No 5 was powered by a 16 hp engine (weight 215 lbs). This took S D on his first trip round the Eifel Tower. That was on 13th July 1901. On 5th August he flew round the tower again when a hydrogen leak let him down. He crashed into houses, the envelope was torn into shreds and the beam jammed against the corner of a building. S D stepped out of his basket unruffled.

That very evening, work started on Airship No 6. The Deutsch de la Meurthe prize of 100,000 francs would be awarded to the first airship to fly from St Cloud, round the Eifel Tower and return within 30 minutes and S D was keen to win it. No 6 proved to be a very capable airship though it had more than its fair share of accidents and was driven down several times. Alberto took it all in his stride. After one of his forced landings he found he was near a favourite restaurant. Repairs were delayed until he had enjoyed a leisurely lunch. |

On 19th October 1901 he launched from St Cloud, cruised round the Tower and landed smoothly at St Cloud 30 mins 40 secs later. It was enough to win the prize, which he gave away.

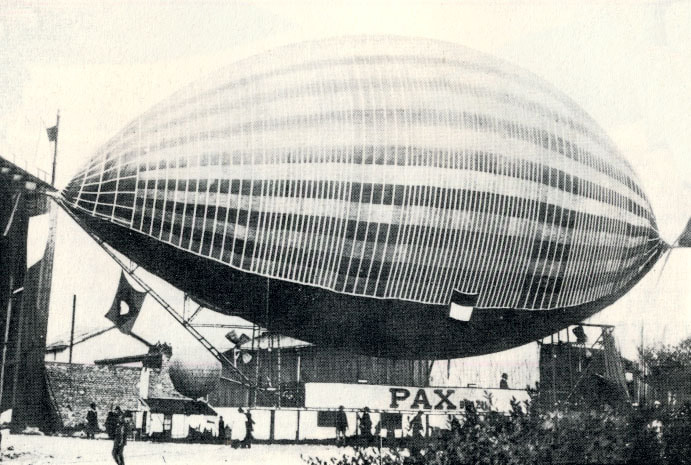

Santos Dumont was a hugely popular figure in Paris partly because of his eccentricities, always calm and polite whatever the circumstances. He did all the testing of his airships himself and seemed entirely unaffected by the tedium of repeated tests nor the ever-present danger of flying these delicate and unpredictable craft. He was not the only airship builder and pilot. The people of Paris enjoyed the spectacle of the great variety of airships flying over - and crashing and into the parks and streets.

Santos Dumont was a hugely popular figure in Paris partly because of his eccentricities, always calm and polite whatever the circumstances. He did all the testing of his airships himself and seemed entirely unaffected by the tedium of repeated tests nor the ever-present danger of flying these delicate and unpredictable craft. He was not the only airship builder and pilot. The people of Paris enjoyed the spectacle of the great variety of airships flying over - and crashing and into the parks and streets.

Alberto’s work went on. Here are Nos 7, 9 and 10.

Alongside all the lighter than air activity there was intense interest in heavier than air flight - aeroplanes. A major promotor of this was the Aero Club de France which had been founded in 1898 by Ernest Archdeacon, a wealthy lawyer and racing motorist. He had learned about the Wrights gliding experiments and had a copy of their 1902 glider built.

It was not a good copy - it had no lateral control and when tested by a keen young volunteer, Gabriel Voisin, it performed poorly. When news filtered through that the Wrights had achieved powered flight, Archdeacon didn’t believe it. He didn’t want to believe it. He intended that France would pioneer powered flight. Hadn’t they pioneered balloon flight and the airship! A heavier than air section was created in the Club. Archdeacon got Voisin to build a glider which could be fitted with engines.

It was not a good copy - it had no lateral control and when tested by a keen young volunteer, Gabriel Voisin, it performed poorly. When news filtered through that the Wrights had achieved powered flight, Archdeacon didn’t believe it. He didn’t want to believe it. He intended that France would pioneer powered flight. Hadn’t they pioneered balloon flight and the airship! A heavier than air section was created in the Club. Archdeacon got Voisin to build a glider which could be fitted with engines.

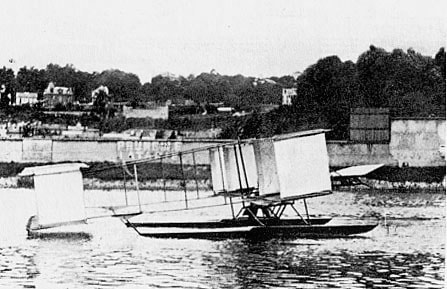

Voisin built two, one in co-operation with Archdeacon and another with Louis Bleriot. Their inspiration seems to have been the boxkite. When towed by a motorboat one of them managed a flight, uncontrolled, of almost 150 yards.

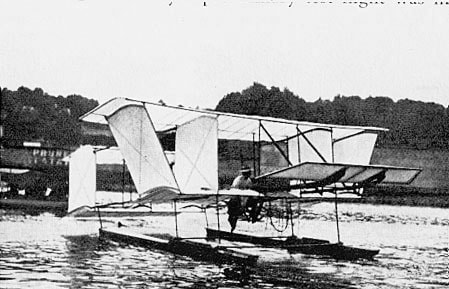

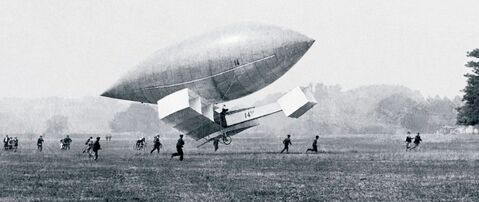

Naturally, Santos Dumont got involved in this frenzy for powered flight in an aeroplane. What emerged might have had some boxkite in it - it did have cellular wings. S D tested it by hanging it under his No 14 balloon (hence the aeroplane got its name, 14 bis. (Bis could mean ‘encore’, or a house squeezed into a row alongside No. 14. It would be 14 bis).

Naturally, Santos Dumont got involved in this frenzy for powered flight in an aeroplane. What emerged might have had some boxkite in it - it did have cellular wings. S D tested it by hanging it under his No 14 balloon (hence the aeroplane got its name, 14 bis. (Bis could mean ‘encore’, or a house squeezed into a row alongside No. 14. It would be 14 bis).

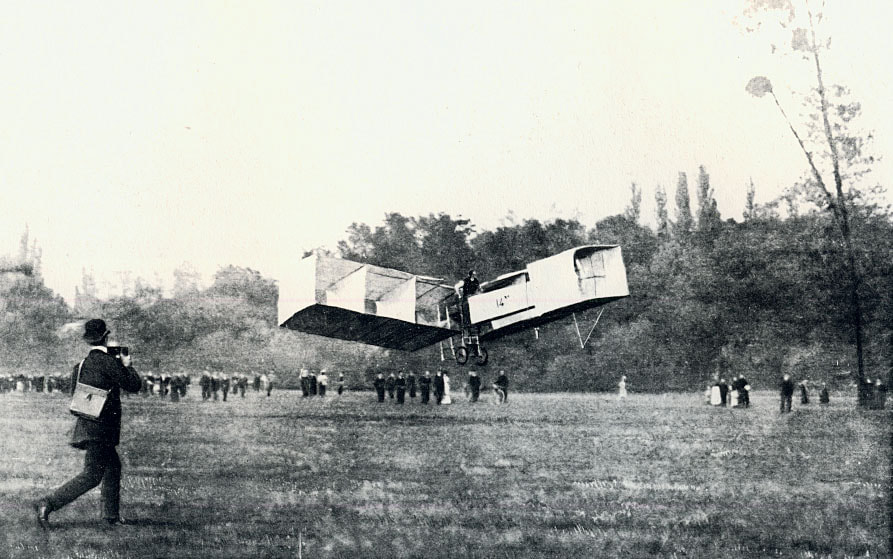

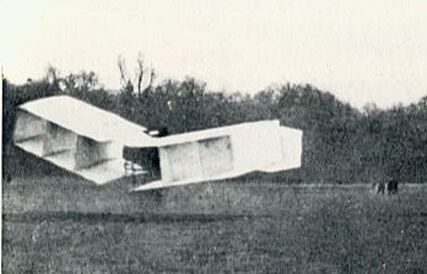

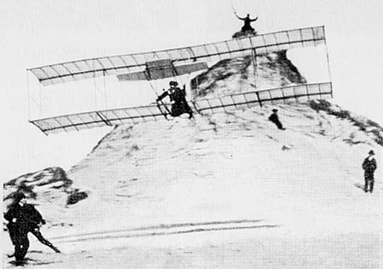

Here it is, skimming along above the ground. What did S D learn from this test? The airship would be flying slower than its usual 15-ish mph, probably no faster than the spectators’ trot, so the controls would demonstrate little effect. Certainly he must have achieved a gentle landing because the wheels didn’t break - as they did on the next two landings when 14 bis flew sans airship.

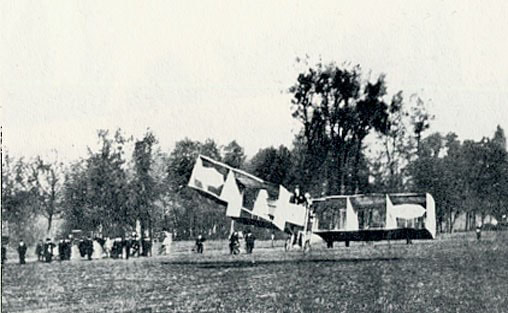

This is the second flight on 23 October 1906. (The first was a 7 yard hop with a heavy landing which broke the wheels, several struts and the prop.) Alberto is standing in one of his wicker baskets and behind him is a 24 hp Antoinette engine. This flight, at an altitude of 10 ft. covered 65 yards - and the wheels broke on landing.

14bis went back to the workshop to have a stronger undercarriage fitted. He changed the engine for a 50 hp driving a metal prop. For lateral stability he had relied on dihedral on the wings. That clearly was not enough so he fitted hexagonal vanes (ailerons?) in the outer wing cells. On 12 November he was ready to fly again and, possibly, win the Aero Club’s prize.

14bis went back to the workshop to have a stronger undercarriage fitted. He changed the engine for a 50 hp driving a metal prop. For lateral stability he had relied on dihedral on the wings. That clearly was not enough so he fitted hexagonal vanes (ailerons?) in the outer wing cells. On 12 November he was ready to fly again and, possibly, win the Aero Club’s prize.

14 bis was in fine form this day and successfully flew five flights between 45 and 90 yards. - with no breakages. Then S D lined up for his last flight covering 240 yards and flying as high as 20 ft. In a final flourish when the aeroplane turned to the left his vanes corrected the turn and he landed smoothly. This flight won him the Aero Club’s Archdeacon Prize of 3000 francs and a supplementary prize of 1500 francs for flying over 100 metres.

Does all this make him the first to fly? Probably not, even if the Wright brothers claim can be discounted because their aircraft was ‘launched by catapult’. But he was certainly the first to fly a powered and controlled aeroplane in Europe. It was indeed a very significant event.

Does all this make him the first to fly? Probably not, even if the Wright brothers claim can be discounted because their aircraft was ‘launched by catapult’. But he was certainly the first to fly a powered and controlled aeroplane in Europe. It was indeed a very significant event.