The Golden Age of Air Racing (US Style). (July 2014)

World War I left the USA with a bit of an inferiority complex, in aviation, at least. Their fighting airman had relied almost entirely on British and French aeroplanes and these types still equipped most of the peace time squadrons. When a race trophy was offered in 1920 by Joseph Pulitzer, a newspaper tycoon, most of the 38 entrants were military pilots flying DH 4s and SE 5as. The event was won by a Verville-Packard VCP-1, a cleaned-up Pursuit design, at a speed of 156 mph. The Pulitzer Race was recognised, by Gen. Billy Mitchell and others, as a good vehicle for encouraging improved performance in military aircraft.

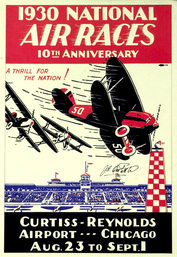

Every subsequent annual race was dominated by military pilots and aeroplanes until 1929 when the Thompson Trophy, a 50 mile circuit race open to all comers, was announced. The race was to be held at Cleveland, Ohio. The new airport there was the first to be owned by a city and was large enough to accommodate the racing at one end, whilst commercial flying continued undisturbed from the new terminal at the other end.

The 10-day event was heavily promoted with a parade through the city of over 200 floats and 21 marching bands. Overhead, three Goodyear airships circled followed by an extensive firework and aerobatic display and the release of 5,000 pigeons. Over 100,000 spectators crowded the viewing stands on the opening day of the airshow.

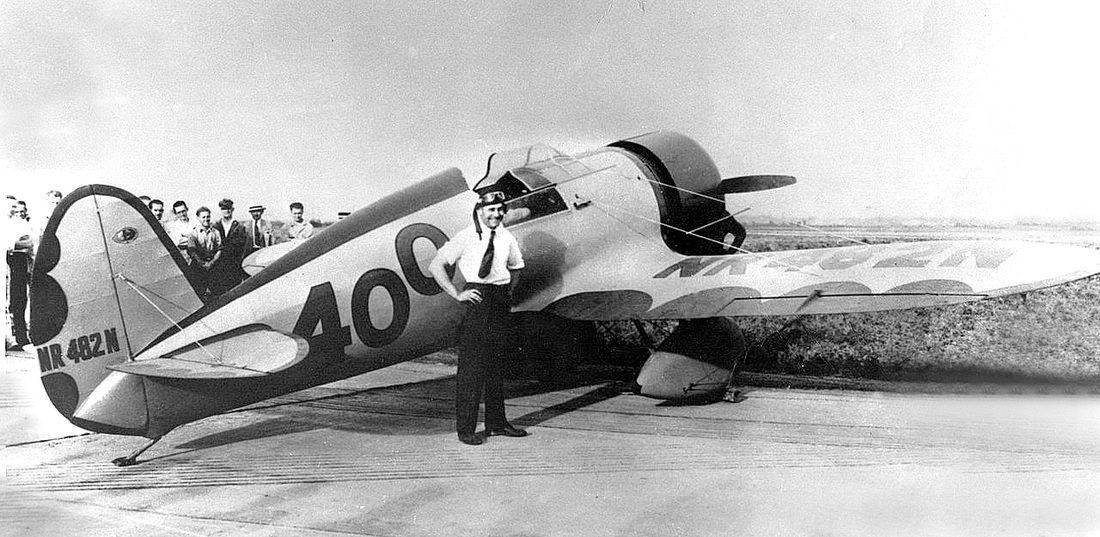

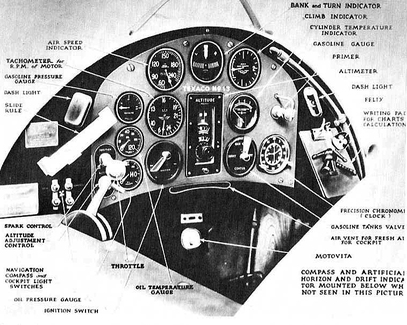

Two young engineers who were working for Travel Air Company, Herb Rawdon and Walter Burnham, thought they could break the military dominance of air racing. Unsure that their boss would approve, they worked privately on the design in their spare time, planning to use a Wright J-6 400 h.p. radial engine, previously thought too much for a ‘light’ plane. When their president, Walter Beech, (whose partners, incidentally, were Clyde Cessna and Loyd Stearman) decided he needed a plane for the new trophy, Herb and Walter said they had just the thing. The racer was built incorporating the then new NACA engine cowl and streamlined wheel pants. Secrecy was maintained by painting over the factory windows to deter local reporters who had printed rumours of a ‘mystery ship’.

Two young engineers who were working for Travel Air Company, Herb Rawdon and Walter Burnham, thought they could break the military dominance of air racing. Unsure that their boss would approve, they worked privately on the design in their spare time, planning to use a Wright J-6 400 h.p. radial engine, previously thought too much for a ‘light’ plane. When their president, Walter Beech, (whose partners, incidentally, were Clyde Cessna and Loyd Stearman) decided he needed a plane for the new trophy, Herb and Walter said they had just the thing. The racer was built incorporating the then new NACA engine cowl and streamlined wheel pants. Secrecy was maintained by painting over the factory windows to deter local reporters who had printed rumours of a ‘mystery ship’.

On its first flights it showed that it exceeded its design speed by 15%. Before the race, it was flown to Cleveland and immediately rolled into a private hangar rented by Beech and covered in tarpaulin.

In the race itself, the Mystery Ship was flown by Doug Davis, an airline pilot. On the second lap he cut inside one of the pylons and flew back to re-circle it. He blacked out in the first turn and wasn’t sure he’d done it properly so he circled it again. Despite this, Davis won handsomely at a speed of 194.9 mph. Civilian pilots took six of the first eight places.

In the race itself, the Mystery Ship was flown by Doug Davis, an airline pilot. On the second lap he cut inside one of the pylons and flew back to re-circle it. He blacked out in the first turn and wasn’t sure he’d done it properly so he circled it again. Despite this, Davis won handsomely at a speed of 194.9 mph. Civilian pilots took six of the first eight places.

The Mystery Ship had raised the bar for race performance. It was produced with two sets of wings, one with the span and chord cropped by 18” and 3” respectively for short races, the other for cross-country events. It was widely demonstrated around the country and was bought by Walter Hunter for 1931 race season. However, before the race, it caught fire in the air and was destroyed after Hunter baled out.

The second model went to Pancho Barnes. With it she won the 1930 Women’s Air Derby and broke Amelia Earhart’s women’s world air speed record with a speed of 196.19 mph. This Mystery Ship was later bought by Paul Mantz and used in film work. It is believed to have eventually made its way to England where it is apparently being restored. As for Pancho, many years later she achieved notoriety as the proprietor of the Happy Bottom Riding Club near Edwards AFB where her customers included Chuck Yeager and Buzz Aldrin.

The second model went to Pancho Barnes. With it she won the 1930 Women’s Air Derby and broke Amelia Earhart’s women’s world air speed record with a speed of 196.19 mph. This Mystery Ship was later bought by Paul Mantz and used in film work. It is believed to have eventually made its way to England where it is apparently being restored. As for Pancho, many years later she achieved notoriety as the proprietor of the Happy Bottom Riding Club near Edwards AFB where her customers included Chuck Yeager and Buzz Aldrin.

|

After the world of air racing was revitalized by the Mystery Ship, it’s interesting to see a little of what happened next. Its dominance was challenged by several designs, most trying to get the largest possible engine in the smallest possible airframe.

A new prize, the Bendix Trophy, was on offer in 1931 for a trans-continental race, initially from Burbank, California to Cleveland (later to Newark NJ). There were only four entries but they included Jimmy Doolittle and Ira Eaker, both to become USAAC generals. Doolittle won in the Laird Super Solution (the solution being the answer to the problem of beating the Mystery Ship). |

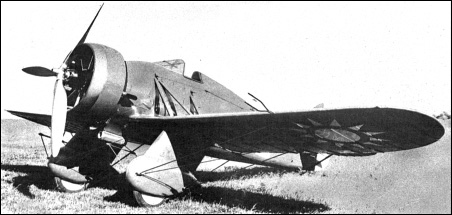

In the Thompson Trophy however, Doolittle’s Solution didn’t fare so well. The company run by the five Granville brothers asked their designer to produce his first attempt at a racer. Just five weeks later the Model Z emerged, powered by a P & W Wasp Junior which produced 535 hp). Only eleven days after its first flight, it won the Goodyear Trophy at 205 mph; three days later there was a victory in the General Tire and Rubber race and two days after that Lowell Bayles triumphed in the Thompson Trophy at 236.24 mph, pushing Doolittle into second place.

After the race, Bayles fitted a 750 hp supercharged Wasp Senior to the Gee Bee to beat the existing landplane speed record of 278 mph. Buoyed by reaching 314 mph on a trial run he was disappointed that his first attempt raised the record by too small a margin to be registered. On the next flight aileron flutter caused the wing to collapse dramatically and Bayles was killed.

For the 1932 races the pilot due to fly a Gee Bee (now modified with increased rudder area) was injured in a crash (in a different Granville model). The seat was offered to Jimmy Doolittle. In a test flight, he discovered how difficult the GB was. Practising a pylon turn, fortunately at some height, he pulled too much g and the GB flick rolled twice. He was grateful for the extra altitude which gave him time to recover. Although he said he ‘didn’t trust the little monster’ and it was like’ balancing a pencil on the end of your finger’, he flew off to Cleveland.

For the 1932 races the pilot due to fly a Gee Bee (now modified with increased rudder area) was injured in a crash (in a different Granville model). The seat was offered to Jimmy Doolittle. In a test flight, he discovered how difficult the GB was. Practising a pylon turn, fortunately at some height, he pulled too much g and the GB flick rolled twice. He was grateful for the extra altitude which gave him time to recover. Although he said he ‘didn’t trust the little monster’ and it was like’ balancing a pencil on the end of your finger’, he flew off to Cleveland.

Before the race he showed the Gee Bee’s straight-line performance by raising the speed record to 296.287 mph. In the race itself he carefully flew wide turns at the pylons and crossed the line alongside the second-place man – who was a lap behind! Shortly afterwards, he announced his retirement from air racing. The Gee Bees went on to enhance their fearsome reputation by killing their pilots, including one of the Granville brothers.

Air racing in the US continues today in the more controlled – but still dangerous – skies over Reno. There are some original and many modern replicas of aeroplanes from the Golden Age, mostly in museums,

Here in the UK there is only one replica from the US Golden Age which we can enjoy. For that our thanks are due to Richard Seeley, who owns this re-incarnation of the Mystery Ship and to Ron Souch who spent four years producing a work of art.