The RAF’s Distance Records (Nov 2019)

Aeroplanes had developed rapidly during the First World War with the stimulus of the need to out-perform the enemy. With peace came the opportunity to use aircraft commercially and the profits from sales financed the design and build of new aeroplanes which could fly further, higher and faster. Manufacturers showed off the capability of their new creations by arranging special flights which attracted the attention of the press – and customers. If possible, they would try to break an existing record. And aviation records could be seen as an indicator of a nation’s technological achievements.

It was this factor that stirred minds in the Air Ministry. In 1927 Britain held no world record. In fact, the last time GB had held a record - the distance record - was in 1919 when Alcock and Brown crossed the Atlantic.

It was this factor that stirred minds in the Air Ministry. In 1927 Britain held no world record. In fact, the last time GB had held a record - the distance record - was in 1919 when Alcock and Brown crossed the Atlantic.

The RAF tried first in May 1927 with a Hawker Horsley bomber. It was fitted with extra fuel tanks and left RAF Cranwell for India. It ran out of fuel before it got there and ditched in the sea off the south coast of Persia, as it was then.

A record had been set – 3,420 miles, but the timing was unfortunate. Just hours after the ditching, Charles Lindbergh landed in Paris, having flown 3,590 miles.

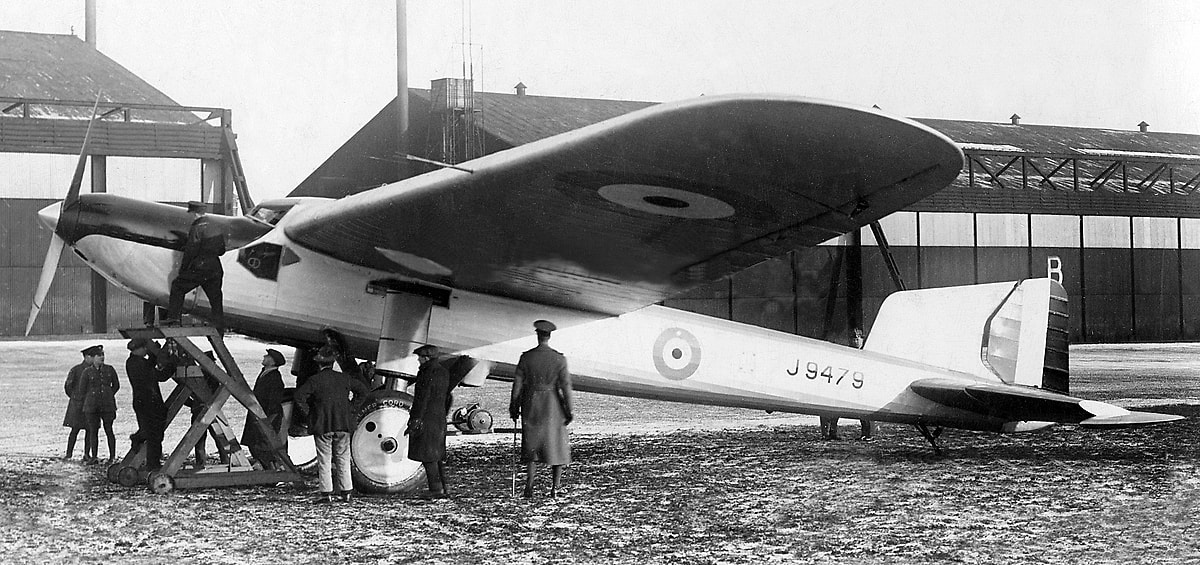

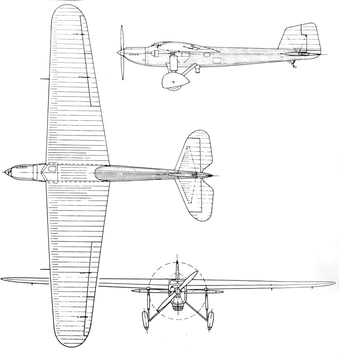

After two more attempts with the Horsley the Air Ministry realised that using an existing service aeroplane to set a record was a mistake and what was needed was a purpose built machine. The result was the Fairey Long Range Monoplane powered by a Napier Lion. Normally this produced 450 hp. With higher compression pistons and modified carburettors that could be raised to 570 hp. The tanks could hold 1000 gallons of petrol, giving a range of over 5000 miles. In recognition of this, behind the two seat cockpit was a small hammock.

After two more attempts with the Horsley the Air Ministry realised that using an existing service aeroplane to set a record was a mistake and what was needed was a purpose built machine. The result was the Fairey Long Range Monoplane powered by a Napier Lion. Normally this produced 450 hp. With higher compression pistons and modified carburettors that could be raised to 570 hp. The tanks could hold 1000 gallons of petrol, giving a range of over 5000 miles. In recognition of this, behind the two seat cockpit was a small hammock.

The Fairey LRM first flew in 1928 and was prepared for a flight to India. It was crewed by two Welshmen, both of whom had served with distinction in WWI. The captain was Sqn Ldr Arthur Jones-Williams OBE, Croix de Guerre, MC and Bar and his co-pilot was Flt Lt Norman Jenkins OBE, DFC, DFM. On 24 April, 1929 they took off from RAF Cranwell and headed for India. The hammock was used as a chair for the navigator. He had side windows, a transparent panel in the floor for checking drift and in the roof a hatch for shooting the stars.

It was a successful flight, but not far enough to claim as a record. So they tried again, this time planning a flight to South Africa. They took off on 16 December 1929, crossed the Mediterranean and flew into the Atlas Mountains in Tunisia. Both men were killed in the crash. The point of impact was just 2,300 ft ASL. However, the navigation log which was recovered from the wreckage recorded that they had been flying at a height of 5,000 ft. Whilst there was speculation that the altimeter somehow had failed no reasonable conclusion could be reached on the cause of the crash.

|

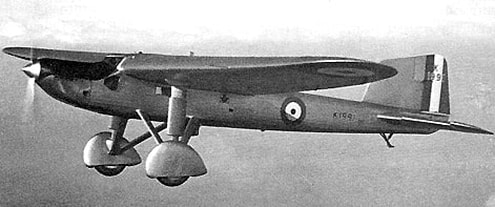

There was obviously determination in the Air Ministry to achieve the record because they immediately ordered Fairey to build another Long Range Monoplane. There were remarkably few improvements to the original design. Externally, spats were added to the wheels, and the fin and rudder were tidied up.

|

Internally, there were more significant changes. A two-axis auto-pilot was fitted, controlling roll and yaw. Three altimeters, four compasses, two airspeed indicators, two turn-and-slip indicators, a pitch and azimuth indicator and an HF radio transmitter for position reporting appeared. (A receiver was deemed to be unnecessary- there was little or nothing to receive from any station along the planned route so why not save the weight). Drift lines were painted on the floor window and a comprehensive set of tables of airspeeds, engine revs and fuel flowmeter readings produced.

The best time for the flight to the southern hemisphere was thought to be around the turn of the year and preferably in a period of full moon. In December 1931 there was just time to fit in a proving flight. The crew chosen for the record attempt were Sqn Ldr O R Gayford and Flt Lt D L G Bett. Gayford had been in the Navy as an RNAS Observer during WWI, earning the DFC. He became a pilot in 1922 and had served in Africa and the Middle East. He would be on familiar territory on a shake-down cruise to Egypt and back. All went well. The only problem arose on the return. Dense fog covered the airfield they were seeking leading to a forced landing in a field near Saffron Walden. The field was rough and the LRM ended on its nose, damaging the prop and one wing tip.

The damage was quickly repaired and the crew waited for a suitable weather forecast. It failed to materialise and eventually the flight was postponed. The team reformed in the autumn but without Flt Lt Bett. He had suddenly fallen seriously ill and died in hospital. He was replaced by Flt Lt G E Nicholetts, a flying boat pilot and a navigation specialist. This time the weather cooperated.

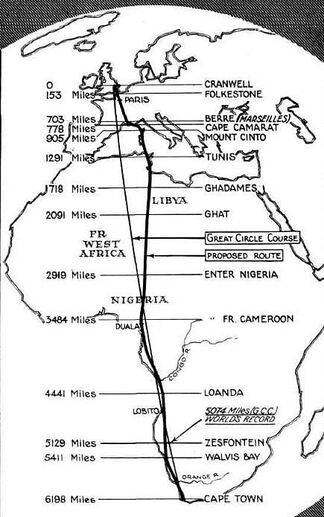

The planned route diverted from the great circle course which ran over the threatening Atlas Mountains. The crew were expected to reach Tunisia about dusk and the French had agreed to burn the lights on all their landing grounds in the Sahara. The critical point on the map is Zesfontein which had to be passed to claim a new record.

The best time for the flight to the southern hemisphere was thought to be around the turn of the year and preferably in a period of full moon. In December 1931 there was just time to fit in a proving flight. The crew chosen for the record attempt were Sqn Ldr O R Gayford and Flt Lt D L G Bett. Gayford had been in the Navy as an RNAS Observer during WWI, earning the DFC. He became a pilot in 1922 and had served in Africa and the Middle East. He would be on familiar territory on a shake-down cruise to Egypt and back. All went well. The only problem arose on the return. Dense fog covered the airfield they were seeking leading to a forced landing in a field near Saffron Walden. The field was rough and the LRM ended on its nose, damaging the prop and one wing tip.

The damage was quickly repaired and the crew waited for a suitable weather forecast. It failed to materialise and eventually the flight was postponed. The team reformed in the autumn but without Flt Lt Bett. He had suddenly fallen seriously ill and died in hospital. He was replaced by Flt Lt G E Nicholetts, a flying boat pilot and a navigation specialist. This time the weather cooperated.

The planned route diverted from the great circle course which ran over the threatening Atlas Mountains. The crew were expected to reach Tunisia about dusk and the French had agreed to burn the lights on all their landing grounds in the Sahara. The critical point on the map is Zesfontein which had to be passed to claim a new record.

|

The Fairey left Cranwell at 7.15 am on 6 February 1933. Cruising at 110 mph they flew over Tunis at 8 o’ clock that evening and 24 hours later were over Nigeria. There dust storms affected the wind driven generator which provided high pressure air for the automatic pilot and that stopped working. Head winds and bad visibility increased fuel consumption and complicated navigation. Happily, they passed Zesfontein and were able to find the airfield at Walvis Bay when they prudently landed – with just 10 gallons left in their tank. They had flown 5,308 miles and had beaten the existing record by 338 miles.

|

Gayford and Nicholetts flew on to Cape Town, their original destination, and then back home by stages. At every stop they were given a heroes’ welcome. Here Gaydon is at the microphone back in England. All that expense and effort had been worth it. Britain was in the record books.

Six months later, two Frenchmen flew 5,657 miles from New York to Syria.

The world record faction in the Air Ministry smouldered on. Re-ignition was sparked by a record set by the Russians (the Russians!) in July 1937. A Tupolev ANT-25 had flown from Moscow, over the pole and landed in California, a flight of 6,306 miles. Four months later the RAF’s Long Range Development Unit was formed at Upper Heyford, commanded, naturally, by Wg Cdr Oswald Gayford. Although he had used a specially built aeroplane for his record it was believed that one of the RAF’s current in-service bombers was suitable for the role.

Its origin arose from a not unusual circumstance. The Air Ministry had issued a specification, G.4/31 for a general purpose biplane and torpedo bomber. Vickers responded and built a biplane, Type 253, to meet the specification. At the same time, as a private venture, they built Type 246, a monoplane which proved to be far superior. The AM cancelled the order for 150 Type 253 and ordered 90 monoplanes, to be known as the Wellesley.

Its origin arose from a not unusual circumstance. The Air Ministry had issued a specification, G.4/31 for a general purpose biplane and torpedo bomber. Vickers responded and built a biplane, Type 253, to meet the specification. At the same time, as a private venture, they built Type 246, a monoplane which proved to be far superior. The AM cancelled the order for 150 Type 253 and ordered 90 monoplanes, to be known as the Wellesley.

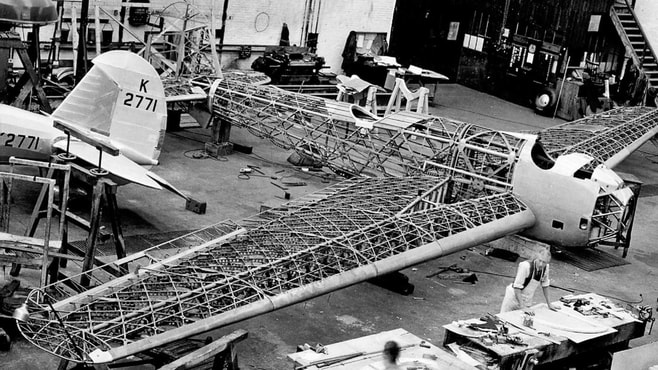

Using Barnes Wallis’s experience in building the R100 airship, the single engined, two seat Wellesley used geodetic construction, a light weight latticework structure of great strength. Powered by a 925 hp Bristol Pegasus engine it carried its 1000 lb bomb load in underwing panniers. 176 were to be produced but they were rapidly outclassed by the Hampden and the Wellington. Wellesley equipped squadrons were moved to the Middle East.

The LRDU reasoned that they could launch their record attempt from Egypt and Australia was a convenient target. To add spice, they would use a formation of four aircraft. Four Wellesleys were selected and fitted with more powerful 1,010 hp Pegasus engines with automatic boost and mixture control. Rotol constant speed airscrews, automatic pilots and long range tanks were fitted. To save weight, oxygen equipment was removed as were parachutes and dinghies (don’t worry chaps, the Navy will positions ships strategically to cope with any ditching). Wellesleys in service had acquired a third seat so the crew would be first pilot, second pilot/navigator and third pilot/wireless operator. Changing pilots in the narrow fuselage would be tricky, especially if the auto-pilot stopped working. It started with the first pilot’s seat back being lowered. What happened next was left to ingenuity and lots of practice.

The first pilot looks back down the fuselage View from the 3rd pilot/radio op’s seat

Everything was ready by July 1938 and the four Wellesleys took off on a proving flight from Cranwell to Shaibah in Iraq. They flew 4,300 miles in 32 hours without any serious problem. Ultimately, it was decided that only three aircraft would fly in the record attempt and they duly assembled at Ismailia in Egypt. The crews, chosen for their fitness and stamina, were -

L2638 L2639 L2680

Sqn Ldr Richard Kellett Flt Lt Rupert Hogan Flt Lt Andrew Combe Flt Lt Nick Gething Fg Off George Musson Flt Lt Burnett

Plt Off Maurice Gaine Flt Sgt T D Dixon Sgt Hector Gray

The formation left Ismailia on 5 November 1938. The first two climbed as planned to 10,000 ft. Andrew Combe found that he couldn’t raise his landing gear. When everything else had failed Burnett, the navigator, cut a hole in the fabric covering of the fuselage. He pushed out the fishing net he had brought to pass things to the other crew members and was able to trigger the right lever on the undercarriage to allow it to retract. It wasn’t until they reached Jask, on the coastline of India, that they caught up with the other two Wellesleys.

Everything was ready by July 1938 and the four Wellesleys took off on a proving flight from Cranwell to Shaibah in Iraq. They flew 4,300 miles in 32 hours without any serious problem. Ultimately, it was decided that only three aircraft would fly in the record attempt and they duly assembled at Ismailia in Egypt. The crews, chosen for their fitness and stamina, were -

L2638 L2639 L2680

Sqn Ldr Richard Kellett Flt Lt Rupert Hogan Flt Lt Andrew Combe Flt Lt Nick Gething Fg Off George Musson Flt Lt Burnett

Plt Off Maurice Gaine Flt Sgt T D Dixon Sgt Hector Gray

The formation left Ismailia on 5 November 1938. The first two climbed as planned to 10,000 ft. Andrew Combe found that he couldn’t raise his landing gear. When everything else had failed Burnett, the navigator, cut a hole in the fabric covering of the fuselage. He pushed out the fishing net he had brought to pass things to the other crew members and was able to trigger the right lever on the undercarriage to allow it to retract. It wasn’t until they reached Jask, on the coastline of India, that they caught up with the other two Wellesleys.

India was crossed in darkness then they ran into a succession of thunderstorms and heavy cloud. Combe had to bank sharply to avoid running into a particularly black cloud and found it very difficult to raise the wing. They flew round in several circles before they got back to level flight. Coombe suspected that the fuel had run to one side of the tanks and unbalanced the aircraft.

Navigation was by dead reckoning with little sight of the ground but they benefitted from an occasional bearing from Singapore which penetrated the static. When they calculated that they had beaten the Russian record Burnett admitted that they celebrated with ‘a nip from my brandy flask’.

Navigation was by dead reckoning with little sight of the ground but they benefitted from an occasional bearing from Singapore which penetrated the static. When they calculated that they had beaten the Russian record Burnett admitted that they celebrated with ‘a nip from my brandy flask’.

The plan was to rendezvous over the Lomblen Islands in Indonesia and to check on fuel levels before crossing the Timor Sea to Darwin. Hogan decided it was prudent to land at Kupang in West Timor and the other two pressed on, flying the last 200 miles in formation. As they circled Darwin, Combe’s wheels lowered normally. The fault was later traced to a broken spring. Kellett had 44 gallons remaining and Combe 17.

When Hogan joined the others he calculated that, despite his landing short, he had beaten the Russian by 350 miles. Kellett and Combe had flown 7,158 miles. Sharing the piloting had worked. Combe had flown 24 hours, Burnett 13 and Gray 11. No one had been able to sleep, but they’d all shaved and looked smart on their arrival.

The trio of crews flew on to Sydney where they enjoyed a ticker tape reception. Visits to other cities were interrupted by forced landings for Kellett’s and Hogan’s aeroplanes, ruining plans for the formation to fly home. So Combe’s dismantled Wellesley and all the crews came home by sea. The crews of the two bombers which reached Darwin non-stop were all decorated, AFC for the officers and AFM for Sgt Gray. To everyone’s disgust, Hogan and his crew received nothing.

The Wellesleys’ record was unchallenged until November 1945 when a B-29 flew 7,914 miles from Guam to Washington.

When Hogan joined the others he calculated that, despite his landing short, he had beaten the Russian by 350 miles. Kellett and Combe had flown 7,158 miles. Sharing the piloting had worked. Combe had flown 24 hours, Burnett 13 and Gray 11. No one had been able to sleep, but they’d all shaved and looked smart on their arrival.

The trio of crews flew on to Sydney where they enjoyed a ticker tape reception. Visits to other cities were interrupted by forced landings for Kellett’s and Hogan’s aeroplanes, ruining plans for the formation to fly home. So Combe’s dismantled Wellesley and all the crews came home by sea. The crews of the two bombers which reached Darwin non-stop were all decorated, AFC for the officers and AFM for Sgt Gray. To everyone’s disgust, Hogan and his crew received nothing.

The Wellesleys’ record was unchallenged until November 1945 when a B-29 flew 7,914 miles from Guam to Washington.